This article was first posted on Geri Walton's own website on 12 March 2022, where the original can be seen here. It appears on our website, in slightly adapted form, by kind permission. Click on the images to enlarge them, and for more information about them, for example, about whether or not they can be reproduced. — Jacqueline Banerjee

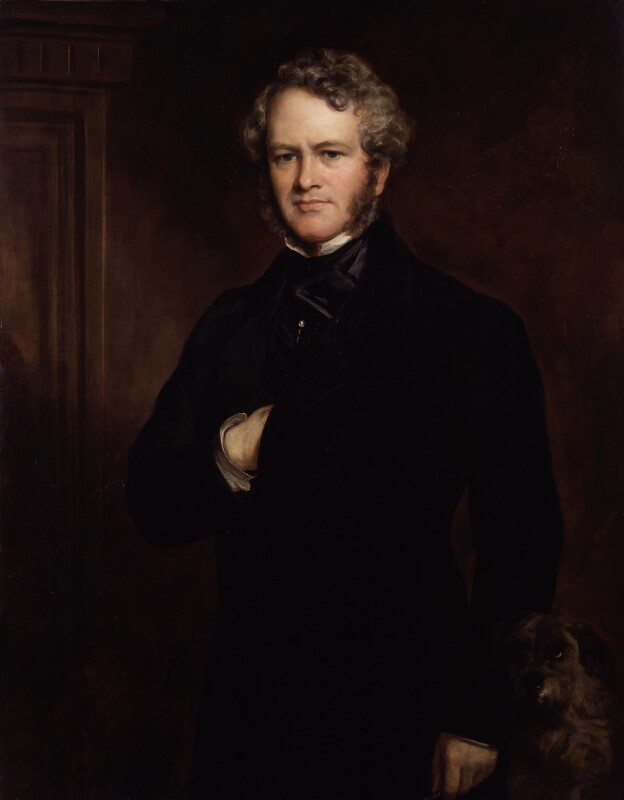

Portrait by Sir Francis Grant, 1852.

© National Portrait Gallery London.

Sir Edwin Henry Landseer, known as Edwin Landseer, was a British artist well known for his animal portraits of horses, dogs, and stags. He was born in London to John Landseer (an engraver) and Jane Potts on 7 March 1802. The Morning Post reported that the young Landseer could draw animals from childhood and that he was "so precocious, indeed, … that long before he was ten years old, he was also a finished draughtsman in the line of animal life, as [could] … be seen by some specimens of his early powers which [were] preserved at South Kensington" (3 October 1873: 5).

Landseer's training and early career

Landseer's artistic talents were also nurtured and encouraged by his father, who frequently sent him into the fields to draw sheep, goats, and donkeys. Of these early times, Eliza Meteyard recorded what Landseer's father once said to a neighbor as they were walking:

Many a time have I lifted him [Edwin] over this very stile. … It was a favourite walk with my boys; and one day when I had accompanied them, Edwin stopped by this stile to admire some sheep and cows … At his request I lifted him over and finding a scrap of paper and pencil in my pocket I made him sketch a cow. He was very young … not more than six or seven years old. After this we came on several occasions, and as he grew older this was one of his favourite spots for sketching. He would start off alone …, and remain until I fetched him in the afternoon. I would criticize his work, and make him correct defects before we left the spot." [qtd. in Stephens 17-18]

As Landseer became more proficient and skillful he attracted the attention of Benjamin Robert Haydon, a British artist who specialized in grand historical pictures. "[He] welcomed him [Landseer] as a constant visitor both at this studio and also at his hospitable home. … About the same time he was admitted as a student of the Royal Academy" (The Morning Post, 3 October 1873: 5). Then in 1815, the same year that the first Duke of Wellington defeated Napoleon Bonaparte at Waterloo, 13-year-old Edwin Landseer achieved success with his first appearance at the Royal Academy Exhibition. The artworks attributed to him at this time included: "'No. 443. Portrait of a Mule, the property of W.H. Simpson, Esq., of Beleigh Grange, Essex;' and 'No. 584. Portraits of a Pointer Bitch and Puppy'" (Stephens 29).

Landseer and Scotland

Landseer's An Illicit Whisky Still in the Highlands (1826–1829)

After achieving success at the Royal Academy Exhibition, it was noted that Landseer "from this time forward … was one of the most constant and industrious of professional painters, scarcely ever letting a year pass by without sending some work or others, and often several, to represent him at the exhibition, which then, … was located at Somerset House, and also in Spring-gardens" (The Morning Post, 3 October 1873: 5). Landseer also became associated with Scotland after his first visit it in 1824. Some of his paintings associated with Scotland included The Hunting of Chevy Chase (1825–26), An Illicit Whisky Still in the Highlands (1826–1829) and his later The Monarch of the Glen (1851) and Rent Day in the Wilderness (1855–1868).

Landseer and the Duchess of Bedford

Study for a miniature of Georgiana Russell, Duchess of

Bedford, 1852. © National Portrait Gallery London.

In 1823 Landseer was commissioned and paid handsomely to paint a portrait of Georgiana Russell, Duchess of Bedford, wife of John Russell, 6th Duke of Bedford. Soon after Landseer began giving the Duchess art lessons and despite her being twenty years older than him, they began an affair. Apparently, her husband appeared to be unaware of their illicit relationship even though she also began to rent Doune House in Scotland as a lover's retreat.

Although Edwin Landseer thought highly of the Duchess not everyone else did. She was described by Thomas Moore, the Irish writer, poet, and lyricist celebrated for his Irish melodies, as being "vulgar and capricious." She was also known to love practical jokes, which Moore deemed to be "unbecoming" behavior for a Duchess. Despite the Duchess' faults, the incredibly handsome Landseer was in love with her. From their relationship came a daughter named Rachel who Landseer never publicly acknowledged as his daughter supposedly because he wanted to avoid having the Duchess suffer any type of scandal.

Landseer's animal paintings

Landseer's Eos, Courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust.

In Landseer's late thirties, he suffered what is now believed to be a substantial nervous breakdown. He was thereafter plagued for the rest of his life by bouts of melancholy, hypochondria, and depression, which were often aggravated by alcohol and drug use along with two head injuries. James Hamilton in his book A Strange Business attributes Landseer's nervous breakdown to the following: "One of the triggers of Landseer's collapse was that the Duchess of Bedford refused, once she had been widowed in 1839, to marry him. … the mental difficulties he encountered after the Duchess rejected him were further rooted in an excess of success, an inability to enable supply to meet demand, and perhaps uncertain contact with reality in life, even though he could vividly describe it in paint."

During Landseer's career he had a desire to create paintings that would not be forgotten. In fact, he once said of his animal paintings, "I wish to bring out …. human feeling and human thought ― endurance, impudence, pain, joy and the rest ― through the medium of animal life" (qtd. in the Sketch: 84). Because he succeeded in doing that, he was particularly popular with the British public during the Victorian Era. Many middle-class citizens had reproductions of his works in their homes and much of his fame occurred because of engravings produced by his brother Thomas.

Scene from A Midsummer Night's Dream. Titania and Bottom

Scene from A Midsummer Night's Dream by Edwin Landseer. Titania and Bottom.

In 1850 Edwin Landseer was knighted, and a year later, in 1851, the wealthy engineer, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, commissioned Landseer to paint Scene from A Midsummer Night's Dream. It was a magical oil-on-canvas and an unusual undertaking for Landseer as he was mainly known for his animal paintings. In fact, this is his only painting of a fairy scene. It depicts the action from the third act of William Shakespeare's play A Midsummer Night's Dream and the painting was first exhibited at the Royal Academy summer exhibition in 1851. The Sporting Magazine called it the "very best picture of the year" and stated: "A more difficult subject to treat could scarcely be imagined, and never perhaps was one better treated. It is works of this kind that draw out and confirm Landseer's extraordinary powers, and our only wonder is that he does not more frequently employ himself upon them. There is not the mere fidelity of the painter, but the true feeling of the poet expressed in every atom of the picture" (108).

Others were also impressed by Landseer's artistic skills in his Scene from A Midsummer Night's Dream. For instance, Queen Victoria remarked that the painting was "a gem, beautifully fairy-like and forceful" (qtd. in Ormond and Rishel 190). Author Lewis Carroll admired the white rabbit in the painting. In fact, that rabbit may have influenced the white rabbit in his book Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.

Other important commissions

Left:Landseer's portrait of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in costume on 12 May 1842. Right: One of Landseer's bronze lions at the foot of Nelson's Column.

Because of his artistic skills, Edwin Landseer developed a personal relationship with Queen Victoria. He was initially hired by her to produce paintings of numerous pets, but his works were so good she then commissioned portraits of ghillies (outdoor servants) and gamekeepers. A year before her marriage to Prince Albert, she also commissioned Landseer to paint a portrait of herself as a gift for new husband. In addition, Landseer gave her and her husband art lessons, produced portraits of their children while they were still babies, and created two portraits of the royal couple in costumes for costume balls that he himself attended.

In 1858 the government commissioned Edwin Landseer to create four bronze lions to be installed in Trafalgar Square. They were to be placed at the base of a monument in Westminster, known as Nelson's Column, which had been built to honor Admiral Horatio Nelson, who died at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. Landseer agreed to create the bronzes if he did not have to start the work for nine months. Unfortunately, the project was further delayed when he asked to be supplied with copies of casts of a real lion he knew were in the possession of the academy at Turin. The request proved complex, and the casts did not arrive until the summer of 1860. Although casting of the lions began shortly thereafter various conflicts along with Landseer suffering ill health resulted in the lions not being installed in Trafalgar Square until 1867.

Edwin Landseer's shadow painting of Queen Victoria. Courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust.

In the meantime, as Edwin Landseer was wrestling with problems related to the bronzes, Prince Albert died in 1861. Queen Victoria wanted a pair of paintings to show the stark difference between the happy times she had spent with her husband and her mourning and loneliness without him. She thus commissioned Landseer to paint two paintings known as Sunshine and Shadow. According to the Royal Collection Trust, the Queen wanted the shadow painting to depict her "as I am now, sad & lonely, seated on my pony, led by Brown, with a representation of Osborne" (qtd. in "Sir Edwin Landseer (1802-73)"). Thus, Landseer created Queen Victoria at Osborne "and … wrote of the painting that 'If there is any merit in my treatment of the composition it is in the truthful and unaffected representation of Her Majesty's unceasing grief – The story should be told by the Picture'" (Ormond and Rishel 190).

Landseer in court!

Landseer was not just busy creating bronzes and paintings. In 1862, he sued some London tailors in Bond Street for the price of two coats ― a walking coat and a dress coat ― because they were misfits. However, the tailors claimed that Landseer had ordered the coats and that when he received them, he complained the collars were too high, which were then altered. However, Landseer then criticized the coats claiming that they "rubbed his hair" and were too "hot and uncomfortable."

By now the London tailors viewed Landseer as an unreasonable customer. They refused to alter them again unless he paid for the alterations. Landseer then sent the coats back with a letter, upon which the tailors promptly returned them to him along with the following note:

"We be herewith respectfully to send you the two coats having again altered them according to the directions you last gave. The alterations you speak of as being numerous and unsuccessful, arise, we think, from your own fault. The coats when first tried on fitted remarkably well, but if you will place your body into unreasonable positions it will require something more than human science to fit you. … We have most unwilling made the alterations you have required, believing them to be unnecessary, and we now find it impossible to please you. With reference to your desire that we should take the coats back, we cannot think to do so. We beg, therefore, to enclose the account, and shall be obliged by an early settlement." ["Sir Edwin Landseer and his tailors," p. 2]

Edwin Landseer was miffed by their letter and refused to pay the tailors. They then took him to court where he complained that such a letter from them was "insulting" and "annoying." He also testified that he never ordered the coats and that in fact the tailors "solicited" him asking to be allowed to make the coats for him. He also maintained that neither of the coats ever fit properly. Moreover, upon trying them on in the courtroom he demonstrated they were "too tight." After summation, the jury agreed and stated the tailors wrong and found in Landseer's favor.

Landseer's later years

Landseer's last few years were marred by mental instability. Although many people thought him a genius, he was unstable and thus unable to paint in his later years. Moreover, at the request of his family, he was declared legal insane in July 1872. At the time of his death on 1 October 1873, three unfinished paintings were found waiting on the easels at his studio. They were Finding the Otter, Nell Gwynne, and The Dead Buck. His dying wish was that these paintings be finished his friend John Everett Millais, which he did.

During Edwin Landseer's long illness Queen Victoria constantly inquired about his health. She learned of his death by telegraph and newspapers reported that she was "deeply grieved" having "always entertained a high personal regard for [him] in addition to her appreciation of his great talents as an artist (having known him for 35 years)" (Morning Post 4 October 1873: 5). The Dublin Daily Express also provided information on his upcoming funeral:

The funeral of Sir Edwin Landseer will leave 1 St. John's-wood road, the house in which the great painter lived and laboured for nearly fifty years, at ten o'clock on Saturday morning. The hearse and its following of mourning coaches will proceed by Portland-place and Regent-street to Trafalgar-square, where the procession, which up to this point will consist of the relatives and immediate friends of the deceased, will be joined by carriages containing almost the entire body of the Royal Academy. Continuing its journey along the Strand and Fleet-street, the procession will reach St. Paul's at twelve o'clock, and with the beautiful and impressive ceremonial of a cathedral choral service Sir Edwin Landseer will be buried not far from Reynolds, Turner, and other famous members of the great Academy of Painters who have passed away. Her Majesty will send a carriage to join the procession, and will be represented by Colonel the Hon. A. Liddell. Several hundred invitations to seats in a reserved space in the cathedral have been issued, but … the invited persons will be lost in the great crowd of people who will desire to pay a tribute of respect to the painter whose pictures are a pleasure and ornament in half the homes of Englishmen throughout the world. … This is the time of year when painters scatter themselves over the face of the earth, and many of the members of the Academy will have to make long journeys in order that they may stand by the grave of Landseer. Yet, from the letters which have already been received, it is certain there will be very few absentees. ["The Funeral of Sir Edwin Landseer," p. 3]

Bibliography

"The Funeral of Sir Edwin Landseer." Dublin Daily Express. 10 October 1873: 3.

Hamilton, James. A Strange Business. Ebook (no page numbers). Simon and Schuster, 2015.

Ormond, Richard, and Joseph Rishel. Sir Edwin Landseer. London: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1982.

"Sir Edwin Landseer." Morning Post. 3 October 1873: 5.

"Sir Edwin Landseer." Morning Post. 4 October 1873: 5.

"Sir Edwin Landseer (1802-73)." Royal Collection Trust. Accessed 8 February 2022.

"Sir Edwin Landseer and His Tailors." Whitby Gazette. 8 February 1862: 2.

The Sketch: A Journal of Art and Actuality. 3 vols. London: Ingram Brothers, 1898: 84.

Sporting Magazine 18. London: Rogerson & Tuxfore, 1851.

Stephens, F. G. Sir Edwin Landseer. London: S. Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1880.

Created 15 April 2022