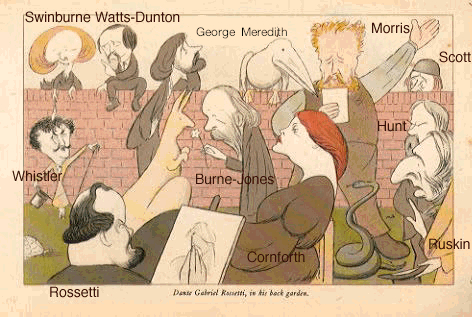

Max Beerbohm's Caricature of the Rossetti Circle — Dante Gabriel Rossetti, in his back garden

Aesthetic Pre-Raphaelitism, the second branch or form of the movement, grew out of the first in the late 1850s under the direction of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. It in turn led variously to the Arts and Crafts Movement, modern functional design, and the Aesthetes and Decadents of the 1890s. Rossetti and his follower Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898) emphasized themes of medievalized eroticism (or eroticized medievalism) and pictorial techniques that produced a moody, often penumbral atmosphere.

Since Rossetti, who was morbidly afraid of criticism, chose not to exhibit his works, Burne-Jones long carried the banner of Aesthetic Pre-Raphaelitism, and it was not until Rossetti's collected works were put on display after his death that the European and British public became widely acquainted with his painting.

Although Rossetti concerned himself far more with philosophical themes than did the Aesthetes and Decadents, his life and art were nonetheless sources of major inspiration for them. His life inspired them because his reclusive, bohemian existence at Cheyne Walk surrounded by his collection of odd animals and blue china proved that one could maintain the life of an Aesthete even in London, the paradigm of modern Philistine urban existence. His works similarly inspired the Aesthetes and Decadents because, as Pater explained, "he knows no region of spirit which shall not be sensuous also, or material" and also because Rossetti believed that human love originating in physical beauty "formed the great undeniable reality in things," the solid substance in a world where everything else might only have the reality of shadows ("Dante Gabriel Rossetti" [1883] in Appreciations, 213).

Rossetti's early short story "Hand and Soul" (1849) also provided a manifesto for Aesthetes and Decadents. It tells the tale of a fictional early Renaissance painter, who, depressed by the failure of his art to improve the world, has a vision in which his soul comes to him in the form of a beautiful woman. She instructs him that he should paint her, his own soul. Such a pronouncement, which provides the program for all Rossetti's later paintings of women, embodies the attenuated romanticism that is the essence of the Aesthetic movement, for it holds that the artist's only duty is to cultivate his own emotions and imagination and then express them.

Rossetti himself in fact devoted considerable effort to conventional themes, particularly in the early poems, but unlike Tennyson and Browning, he had no interest whatsoever in science or religion, and his serious concern with the problems of time and identity issued forth in an abstract poetry of mood that depends heavily upon poetic artifice. Like Swinburne, from whom his poetry otherwise differs in so many important ways, Rossetti's skepticism produced a poetry whose complex personifications and poetic figures within figures free language from its referents. The works of both men, which embody some basic emphases of structuralism and post-structuralism, emphasize music and mood and at times appear to have achieved the status of self-referential artifacts.

Related Material

- Harry Quilter on Burne-Jones, Pater, and Swinburne — Founders of Later Pre-Raphaelitism (1880)

- Cormell Price, Oxford companion of William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones

- Some European descendants of Pre-Raphaelitism: Khnopff, Klimt, Klinger, and Others

Last modified 8 October 2012;

Thanks to Jay Rosenthal for catching a broken image