This review is reproduced here by kind permission of Professor Bury and the online inter-disciplinary journal Cercles, where the review was first published. The original text has been reformatted and illustrated for the Victorian Web by Jacqueline Banerjee. [Click on the following images for larger pictures and for more information about them when available.]

Though printed in smaller characters, subtitles are often more informative than titles about the actual contents of books. Such is once again the case with Victorian Visions of War and Peace, which seems to convey the almost metaphysical promise of an extremely wide scope for a volume which is much more appositely described by a subtitle including the phrase “in the British Empire.” In these our post-colonial, decolonising times, adjectives like “colonial” or even “imperial” may have been judged too dangerous to be included in a title, and the author himself does address the issue in his Conclusion: "what is needed is a ‘recolonisation’ of art history, a problematisation of insular national canons through a more sustained critical engagement with the visual archives of empire and a greater appreciation of the diverse cultural agencies that have constituted British artistic traditions" (236).

Indeed, Sean Willcock’s book concerns more specifically the relations between the conquerors and conquered as depicted by artists (at least one of them belonging to the second group) in a period characterised by the apparition of new modes of popular visual imagery: the focus is not on “high art”, except in the last chapter, but rather on journalistic illustration and even more on amateur or professional photography, generally of documentary nature. Willcock studies the Victorian era’s three key modes of visual spectacle: an ethnographic complex, in which the Other and their objects were documented and displayed according to colonial taxonomies; a diplomatic complex, in which international sovereignties were composed according to aesthetic criteria; and a military complex, whereby warfare was waged and consumed with an eye to its dramatic impact (232-234).

The Indian Court. John Nash's The Great Exhibition: India No. 4. Watercolour and gouache over pencil on paper. Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2016, RCIN 919942. Cat. 6.

Through their representations, artists were “instrumental in constituting the colonial encounter” (2) and could make the empire intelligible. The book starts with the Crystal Palace Exhibition, marked by a new “pictorial grasping” of the world (7), and ends just before the Scramble for Africa, when new technologies like handheld cameras and cinema turned the artist into “an inconvenient witness to imperial atrocities” (240). Geographically, Willcock’s eight chapters do not extend much beyond an area going from India to Burma, the main event being what should apparently no longer be called the Mutiny but the Indian Uprising.

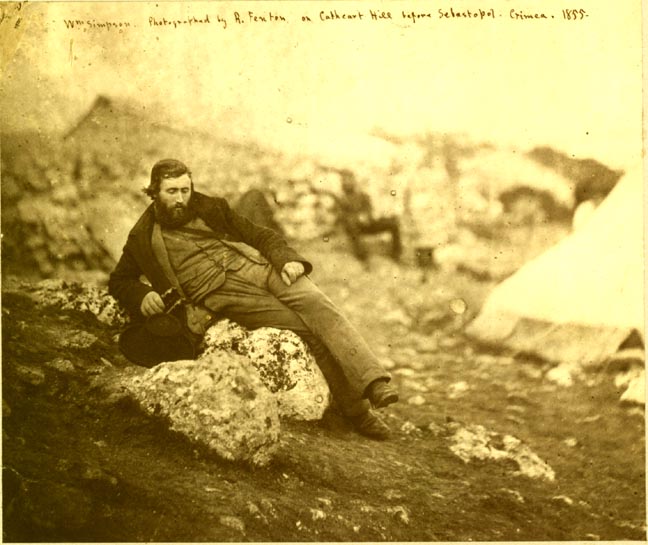

The war artist William Simpson on Cathcart Hill in the Crimea, before Sebastopol, photographed in 1855 by Roger Fenton.

The first chapter is a survey of mid-Victorian cultural consumption of the arts of peace and war. While they were taken as incontrovertible evidence, Roger Fenton’s pictures from Crimea only offered a clean, dignified vision of the conflict, as the photographer had arrived in the final stage of the conflict. Strangely enough, Dr John Murray’s work was also perceived as a source of reliable information, though he exhibited photographs taken in India before the uprising: it was considered in England that his mainly architectural views could be scrutinised “as the privileged means of comprehending warfare” (41). Photographic realism, just like artistic naturalism, was the right answer to the “bestiality” of the rebels: in a speech delivered at the South Kensington Museum in January 1858, Ruskin denounced Indian art as abstract, cut off from nature and therefore from God.

Sean Willcock then focuses on the interesting case of Ahmad Ali Khan, from Lucknow, an Indian architect and amateur photographer who was accused of providing military help to the insurgents with his pictures of buildings. The mastery of a sophisticated technology by a native appeared as a form of “epistemic disobedience” (50), turning the British into objects rather than subjects and challenging the “racist hierarchy of vision” which defined the Indians as an anti-modern and optically challenged people (56-57). After the Uprising, the Photographic Society of Bengal was purged of one of its Indian founders: all Indian members resigned in protest, and were only readmitted in 1862, the first to be readmitted being Ahmad Ali Khan.

Though eschewed by some as inacceptable, graphic violence was not totally absent from the photographs taken in India in 1857: Felice Beato captured some of the “exemplary executions” staged as part of the new “colonial military doctrine of counter-insurgency that relied on spectacular displays of ‘demonstrative’ violence” (236). While the codes of the picturesque allowed him to situate the horrors of war within a familiar aesthetic register, explicit pictures of atrocities are relatively rare in archives: faced with photographs of hangings, Victorian reactions varied “from malevolent thrill to censorious distaste” (74), such an “indecent” practice amounting to psychological terrorism.

The second half of the nineteenth century was also a time of “special war artists,” “embedded” draughtsmen who could operate under fire much more easily than photographers, as they did not need any cumbersome apparatus, but simply some paper and pencils. Sketches had another superiority over snapshots: they offered an insight rather than a mere sight, they gave sense to a picture, by eliminating superfluous details. And they participated in a culture of masculine bravado, asserting the heroism of those journalists who shared the hardships endured by soldiers.

Left: Suppression of the rebellion in 1857, by an unknown photographer, from the New York Public Library collection (ID 5194). Right: A print thought to have been based on a photograph of about 1857 by Ahmed Ali Khan. Sir Henry was in line to be acting Governor-General of India when he died in the Uprising.

Diplomacy was another kind of imperial spectacle that could be commemorated, either through paintings, as had been the case in the previous century, or through photographs and engravings, as part of “the illustrated press’s ‘regime of visibility’” (136). Often equated with the cannon, the camera could also be an instrument of coronation, the fact of accepting photographic capture being perceived as the sign of a more advanced degree of civilisation than the resistance sometimes manifested by Asian monarchs. The locals, who were the objects of the imperial gaze, often knew photography as a process rather than a final product, the prints being reserved for the European consumers of “ethnographic surveillance.”

Dr John Nicholas Tresidder’s private album is a fascinating instance of post-war reconciliation: it was assembled between 1858 and 1864 in Cawnpore, the town which remained associated with the massacre of hundreds of British prisoners by Sepoys (or rather by butchers wielding meat cleavers, the soldiers having refused to kill the women and children imprisoned in a bungalow). By gathering portraits of natives and colonial administrators, Tresidder created a “virtual reconstruction of Anglo-Indian society” (187-188), in a healing, inclusive approach.

The Imperial Assemblage held at Delhi, 1 January 1877, painted by Valentine Cameron Prinsep, 1838-1904. Signed and dated 1877-80.

Another gathering was represented by painter Val Prinsep on his huge canvas of The Imperial Assemblage held at Delhi, 1 January 1877, which was denounced as an “aggressive ocular assault” [202] when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1880. Aesthetic failure was considered inevitable, as if this reunion of Indian monarchs in their garishly coloured finery reflected the impossibility for the British “to envision (and perhaps even administer) their multiracial empire as a viable political entity” (207).

Related Material

- Review of Artist and Empire: Facing Britain's Imperial Past, ed. Alison Smith, David Blayney Brown, and Carol Jacobi

- Nineteenth-Century Photography: A Timeline

- Photographic Interventions and Identities: Colonising and Decolonising the Royal Body

Bibliography

Willcock, Sean. Victorian Visions of War & Peace: Aesthetics, Sovereignty & Violence in the British Empire, c. 1851-1900. New Haven and London: The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art (distributed by Yale University Press), 2021. Hardback. 278 pp., 106 colour illustrations. ISBN 978-1913107246. $65 / £40.

Created 21 March 2022