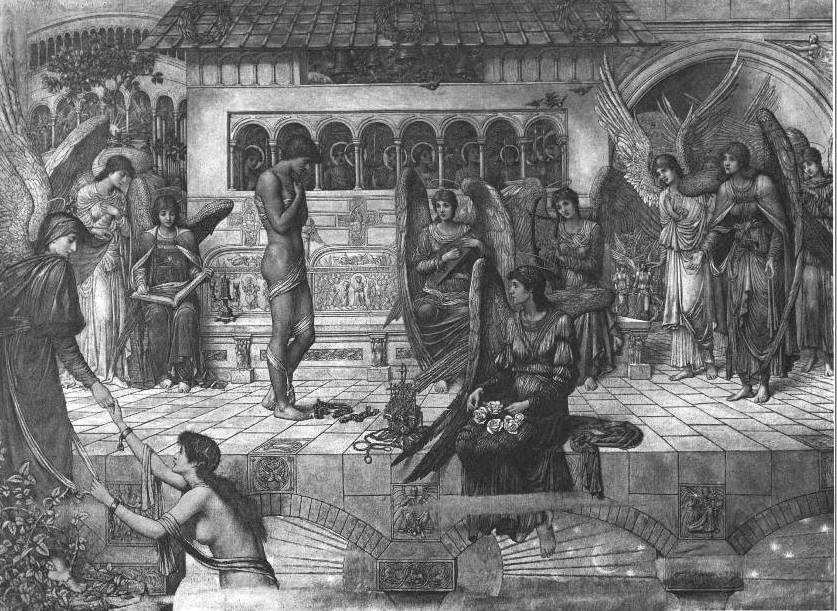

The Ramparts of God's House, by John Melhuish Strudwick (1849-1937). 1889. Oil on canvas. 24 x 33½ inches. (61 x 85.1cm). The Pérez Simón Collection, image courtesy of Christie's, London, not to be reproduced; right click disabled.

Commentary by Dennis T. Lanigan

The Ramparts of God's House was exhibited at the New Gallery in 1889, no. 13, and is one of the most beautiful and best known of Strudwick's works. A spell-binding composition, it exemplifies what G.B. Shaw said characterizes Strudwick's work: "The conception of the Strudwick picture is as exhaustive as the execution; and this is what makes it so thorough and impressive. You sometimes remember a Strudwick better than you remember even a Burne-Jones of the same year" (100-101).

Steven Kolsteren has interpreted this work, but unfortunately at a time when the painting was lost and known only from a less than adequate photograph in the Witt Library at the Courtauld Institute:

"The Ramparts of God's House … illustrates the soul's arrival at the gate of heaven. The narrative starts in the lower left-side corner. An angel assists the male [female] soul, climbing from the clouds (the first horizontal level) to a balcony (the second horizontal level). The movement proceeds via an angel with a musical instrument and another angel with a book on her knees, to another soul, who has just freed himself of earthly shackles. He is standing before three angels: two musicians and one with roses in her lap. Other angels proceed from an arched doorway, unseen by the soul. Behind, holy souls are visible in an arched building (the third horizontal level). The building acts like a screen, closing off Heaven itself. The three groups of angels and three arches of the balcony introduce a triple vertical division echoed in the composition of God's house: a semicircular courtyard, arcade and large porch. These subdivisions isolate the principal figure, the male soul, motionless and awaiting, his front in shadow. He symbolizes the stillness of the moment out of time, indeed the liberation from time. [7]

Véronique Gerard-Powell has also attempted to interpret the meaning of Strudwick's painting:

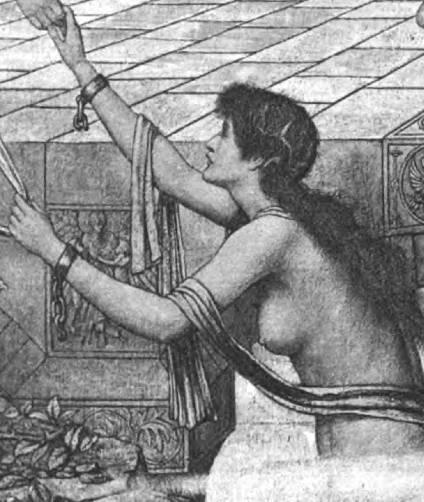

The picture depicts the arrival in Paradise of two souls. Freed from the chains of sin, a humble, naked man is received by the angels, his bodily shell made beautiful. Below, his female companion climbs the remaining steps past the brambles that separate her from the eternal abode. With her wrists still manacled, but no longer chained together, she clings to the robe of an angel who turns to draw her up. The treatment of the subject is highly unusual. Paintings of the Middle Ages and Renaissance tended to show souls in the pastoral beauty of Paradise while in the seventeenth century artists were more concerned with the representation of pleading souls in Purgatory. [177]

The painting had been commissioned by Strudwick's principal patron, William Imrie, who was a man of profound religious convictions. Gerard-Powell points out that both Strudwick and Imrie must have been familiar with the Book of Enoch, a non-canonical book that wasn't included in either the Jewish or Christian bibles because of its questionable authorship and because it was not considered divinely inspired. They may have been familiar with it through a translation completed in 1822 by Richard Laurence, a Professor of Hebrew at Oxford, which allowed the text to reach a wider audience. Although Strudwick did not paint a literal interpretation of it, several elements of his painting seem to have been inspired by it, particularly the account of the vision of Enoch's ascent to heaven to plead the cause of the fallen angels. The construction of Strudwick's picture follows the account of the ascent to the richly decorated celestial abode, minus the flames (Gerard-Powell 177). Gerard-Powell feels the staircase built above the firmament is reminiscent of that at the fifteenth-century Palazzo Contarini del Bovolo in Venice. She sees the influence of Edward Burne-Jones in the elegant, slender feminine forms of the angels and the proportions of the naked man (177). The incense burner, found to the left of the centrally seated angel on the balcony with white roses on her lap, is a copy of one found in an engraving by the Alsatian artist Martin Schongauer of c. 1480.

John Christian also found many signs of the influence of Edward Burne-Jones on this work, although obviously blended with that of others:

There are many echoes of Burne-Jones. The man conforms to his male type, and the seated angels recall those in The Morning of the Resurrection, exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1886. The roofed structure in the centre suggests that Strudwick was aware of Burne-Jones's designs for Arthur in Avalon (Ponce, Puerto Rico), begun in 1881, and the angels seen through the colonnade take up an idea he had already employed in The Wise and Foolish Virgins, his Grosvenor picture of 1884, which in turn seems to have been inspired by Burne-Jones's early pen-and-ink treatment of the theme. [98]

Contemporary Reviews of the Painting

The critic of the Art Journal mentioned the picture only briefly but still found it praiseworthy: "J. M. Strudwick's painting, in a subdued colouring throughout, is distinctly worthy of notice and praise; it is original in choice, and carried to a marvellous finish" (191). F.G. Stephens in the Athenaeum had his usual reservations about Strudwick's pictures, however, finding them too derivative of early Italian art:

Mr. Strudwick's Ramparts of God's House (No. 13), angels and souls redeemed from bonds and death meeting on a sort of terrace of that Italian Gothic architecture which is affected by a certain school of enthusiasts, and is consecrated to subjects of the kind, because the early Italian artists - without whose authority Mr. Strudwick would not move a finger - employed it, is very pretty, carefully finished, and as smooth as stippling can make every fold of the pipe-like draperies, every feature, limb, and ornament, every element of the building. It is a Rossetti-ish version of a Mantegna or a Mocetto, with a few touches of Crivelli, without the virility of the Englishman or the simple and sincere inspiration of the Lombards or Venetians. [688-89]

In fact, a reviewer for the Builder found the painting rather puerile:

Mr. Strudwick's Ramparts of God's House (13), well executed no doubt, is one of the most childish of the mediaeval naïvetés to which a certain class of artists treat us now. Angels stand about on a platform built on arches which descend into clouds and stars, and a nude woman, with the long chin introduced by Mr. Burne Jones, is politely handed up out of the clouds by an angel. If these long-chinned women are admitted into Heaven, it will hardly be worth going to. Behind the platform is an arcaded building with angels looking out through the arches, and a red-tiled roof over it! That is Mr. Strudwick's intellectual conception of the celestial mansions. [332]

The Magazine of Art felt this work was inspired by a famous poem by D.G. Rossetti: "Of this school Mr. Strudwick is the most accomplished member, but his Ramparts of God's House, the subject of which was no doubt suggested by Rossetti's "Blessed Damosel," is not a good specimen of his art. [290]

On the other hand, and not surprisingly, George Bernard Shaw praised the picture in his article on Strudwick in the Art Journal in 1891. He declared that "Transcendant expressiveness is the moving quality in all Strudwick's works; and persons who are fully sensitive to it will take almost as a matter of course the charm of the architecture, the bits of landscape, the elaborately beautiful foliage, the ornamental accessories of all sorts, which would distinguish them even in a gallery of early Italian painting" (101). Richard Muther, in his book on modern painting, was also very positive about it, considering this to be Strudwick's "most celebrated picture": he thought that the angels receiving the naked man were "marvellously spiritual beings filled with a lovely simplicity and revealing ineffable profundity of soul, beings who partake of Fra Angelico almost as much as of Ellen Terry. Their expression is quiet and peaceful. Instead of marvelling at the new-comer, they gaze with their eyes green as a water-sprite's meditatively into illimitable space." Muther also enjoyed the background, finding it "entirely symbolical, as in the pictures of Giotto. A little house with a golden roof and gilded mediæval reliefs is inhabited by a dense throng of little angels, as if it were a Noah's-ark. The colour is rich and sonorous, as in the youthful works of Carlo Crivelli (196).

Details picked out on the original page by George P. Landow, in this order, left to right: (a) Imploring angels at right. (b) Female figure at lower left whose chains have been broken. (c) The recording angel. [Again, right click disabled.]

Related Material

Bibliography

Bate, Percy H. The English Pre-Raphaelite Painters, Their Associates and Successors. London: George Bell and Sons, 1910, 110.

Christian, John. Fine Victorian Pictures, Drawings and Watercolours. London: Christie's (4 November 1994): lot 104, 96-98. https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-3109551

"Current Art. The New Gallery." The Magazine of Art XII (1889): 289-90.

Gerard-Powell, Véronique. A Victorian Obsession. The Pérez Simón Collection at Leighton House Museum. London: Leighton House Museum, 2014. 176-77.

Kolsteren, Steven. "The Pre-Raphaelite Art of John Melhuish Strudwick (1849-1937)." The Journal of Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic Studies I: 2 (Fall 1988): 7 and 11, no. 18.

Muther, Richard. The History of Modern Painting. Vol. III. London: J.M. Dent, 1907.

"The New Gallery." The Art Journal LI (1889): 191.

"The New Gallery and The Grosvenor." The Builder LVI (4 May 1889): 332-33.

Shaw, George Bernard. "J.M. Strudwick." Art Journal (1891): 97-101 Hathi Trust Digital Library version of a copy in the University of Michigan Library. Web. 8 April 2014. [This was the original source for this web-page, as put online by George P. Landow; see the full text of Shaw's article which he provided.]

Stephens, Frederic George. "Fine Arts. The New Gallery." The Athenaeum No. 3213 (25 May 1889): 668-70.

Created 8 April 2014

Last modified (colour reproduction and new commentary added) 5 October 2025