n

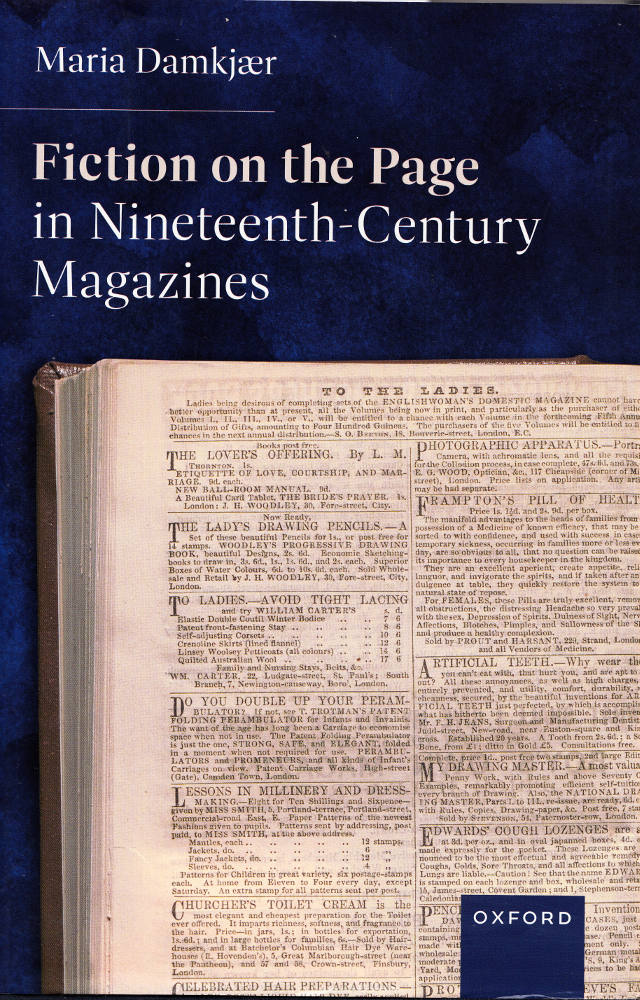

the opening chapter of Fiction on the Page in Nineteenth-Century

Magazines (2025), Maria Damkjaer argues that in the age of the mass-market Victorian

periodical, genre was a fluid and and unstable concept, so that

scholars of Victorian literature, as well of social and literary

history, must accommodate themselves to the fact that periodical and

part-publication deferred rather conferred the status of works

published ephemerally. What appeared in the pages of popular

periodicals, and even such literary journals as Dickens's

Household Words, presented the reading public with texts that could be read

within the conventional expectations of several genres at once.

n

the opening chapter of Fiction on the Page in Nineteenth-Century

Magazines (2025), Maria Damkjaer argues that in the age of the mass-market Victorian

periodical, genre was a fluid and and unstable concept, so that

scholars of Victorian literature, as well of social and literary

history, must accommodate themselves to the fact that periodical and

part-publication deferred rather conferred the status of works

published ephemerally. What appeared in the pages of popular

periodicals, and even such literary journals as Dickens's

Household Words, presented the reading public with texts that could be read

within the conventional expectations of several genres at once.

In her introduction and first chapter, Damkjaer introduces readers to journals about which they have likely never heard, such as The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine and the short-lived Home Circle, as well as some, such as Lloyd's Entertaining Journal, which were popular from the 1840s onward. Damkjaer focuses on the 1840s and 1850s when publishers of these "lesser periodicals" veered from the sombre matter and tone of such well-established cheap periodicals as The Penny Magazine and Chambers's Magazine. As the market was expanding, and readers were hardly high-brow, the new popular magazines strove for "a more irreverent, provocative style and genre usage" (3). Of course, there were what we would recognize as short stories and novels in serial, genres intended to improve as well as entertain readers. The new, low-brow periodicals directed at "upwardly mobile laborers and the lower-middle classes" (3) aimed merely to entertain while providing good value. To this latter point: Blank space was anathema to this new species of journal. A printer typically kept a balam (utility) bag of fillers, to be tacked onto the end of an article in order to avoid following it with blank space.

The relevant genres were those that we recognize today: the novel (serialised), the short story, the book review, and the advice column. However, in these new periodicals, genre was so flexible that "readers did not always know what they were going to be reading" (7), simply because these new magazines did not adhere to the genre conventions of canonical writers such as George Eliot. "By paying attention to genre markers and their manipulation,” Damkjaer finds “a less stable, more negotiable print market" (7). In her view, these new periodicals destabilized genre and "recontextualized" text. Their treatment of texts differed significantly from the literary journal which "rescued" (that is, elevated) a periodical piece by presenting it as a recognized genre, such as fiction, poetry, or essay, when the piece appeared, as it inevitably did, in volume form. Unlike the high-brow publications, these low-status journals did not rescue texts; rather, they published "low-status genres like journalism" (13) and hybrid texts in which two or more genre functions (such as entertaining and advertising) operated simultaneously.

Damkjaer’s book contains an extensive introduction plus seven chapters, bibliographies of primary and secondary sources, and an index. Conveniently, Damkjaer concludes her introduction with a chapter-by-chapter overview intended to orient the reader and telegraph the book's trajectory from the treatment of blank space, "the act of filling made visible" (23), in Chapter 1, through the culminating chapter, "Master Humphrey's Clock and the Print Imaginary." Even Dickens, it seems, engaged in product placement and crossed genre boundaries, as when Samuel Pickwick made a sudden appearance in Dickens's 1840-41 literary journal, which was his vehicle for serialising his fourth and fifth novels, The Old Curiosity Shop and Barnaby Rudge; or, The Riots of 'Eighty.

Questions of genre — what constitutes genre and how the presentation of a text on the printed page affects readers’ perceptions of a text’s genre — absorb Damkjaer in her introductory remarks. But in her discussion of “text fillers” in the next chapter she offers examples of more than just bottom-of-the-column witticisms and curt observations in terms of what she calls the "vignette story" or "the story in scenes." Her purpose, she writes, "is to tease out some very specific aspects of the relationship between fiction and its print conditions, to look for concrete traces of a response to [available] space." To do this, Damkjaer explains, entails “choosing fictions that are likely to show that labour, to show fractures along the tension points between physical space and the content that fits into it.” Damkjaer focuses on "short fiction" rather than "novel-length examples" because "[longer] serials were bankable content and represented an investment of space time, and money for the periodical, so they tended to take production precedence, and therefore tended to have most evidence of editing smoothed out" (52).

Compositors and editors used design features to show readers immediately what was of value on the page (such as the text of a novel in serial) and what was marginal. Magazine readers could readily distinguish, for example, between creative content and page fillers. They understood the significance of these design features and used them to navigate the page. As Damkjaer notes, “[t]o fill the space, editors, authors, and typesetters reach for their tools: asterisks, rules, leading, amusing titbits, things worth knowing, jokes.” Readers recognized and interpreted these cues to guide their reading. “Page fillers are traces of the negotiations inherent in genre formation: that purposes can be multiple and forms can be shifting” (50).

One constant in all this fluidity was the periodical publisher's self-promotion. To fix a publication’s name in readers’ minds, publishers of popular periodicals often adopted such "self-referential" (92) practices as alluding to the periodical in their fictions. As part of a branding strategy such a magazine would often feature an article or story that actually mentioned the magazine's own name, as was the case in the Welcome Guests's first Christmas number (1858), which contained the story "All the Welcome Guests at Hawley Grange; with some Particulars of the Unwelcome Guest and his Abominable Behaviours on the Occasion." Such self-promotional name-dropping might even go so far as the magazine's mentioning itself in a story such as the protagonist Effie's receiving among her birthday presents in "Two Birthdays" (17 January 1880) a copy of The Girl's Own Paper.

Left: Charles Dickens as he appeared in Harper's Weekly (24 November 1860): 740 — "taken from a very recent photograph."

In Chapter Three, "Editorial Insertions and Erasures," Damkjaer discusses advertising language and product placement as strategies that destabilized narrative fiction in popular periodicals, leading her to consider genre hybridity. Despite the obvious flags of plugging a product or service in such a way that the reader could readily access or purchase it, “the overall genre and social action of the host text is not fundamentally changed” (77). At the close of the chapter, Damkjaer moves beyond the self-promotional practices of women's and children's magazines of the 1840s and 1850s to address the self-promotional editorialising of journalist and illustrator George Augustus Sala and the fledgling novelist Elizabeth Gaskell. In particular, she investigates Gaskell’s attempt (immediately erased by her editor, Dickens) to include a topical allusion to Pickwick in her early, episodic novel Cranford in Household Words (13 December 1851). In that third instalment of the Cranford serial, Gaskell has Miss Jenkyns, her foil to the protagonist Captain Brown, "deeply engaged in the perusal of a number of 'Pickwick,' which he has just received" (98); Brown subsequently is killed by a train as he heroically attempts to rescue a child. Would this allusion really have looked to Dickens's readers in 1851 as product placement or was it, as a Victorian might have said, "sheer puffery"?

Damkjaer's exploration of Dickens's motivation for erasing the historical allusion and replacing it with an allusion to the poetry of Thomas Hood will particularly interest those readers who are seeking insights about the editorial psychology of the leading novelist of the period in his own cheap weekly journal.

Gaskell's aim with the Pickwick reference had been to suggest a reciprocal link between her story and the surrounding periodical — she imagined her readers reading a joke about Boz [Dickens's original nom de plume] in the magazine edited by Boz. The act of projecting herself into the printed space, and into the reading lives of the Household Words consumers, was too close to product placement for Dickens, whatever he might have chosen to call it. When he imagined the reading process, he saw a risk that readers would interpret it all as a piece of self-promotion [...] (99)

More than a little miffed at Dickens's erasure, Gaskell later restored the allusion to Pickwick in the 1853 volume edition of Cranford. Of course, by this point the allusion no longer carried the suggestion or taint of product placement, nor was the story any longer a hybrid of fiction and periodical advertising.

The publisher Samuel Beeton was no Charles Dickens, but through his publishing house he churned out a number of mass-market magazines. One of his self-promotional gimmicks was referring to his own publications in those magazines. For instance, he plugged a serially-issued cookbook by his wife, Isabella Mary Beeton, in The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine (October 1859). By the time the best-selling Mrs. Beeton's Book of Household Management, also known as Mrs. Beeton's Cookery Book, finally appeared in volume form in 1861, its authority was well established by its serial instalments. But its reign as the period's supreme household management book began with something else: a shamelessly self-promotional little story, "'Whatever Shall I Do?’ A Tale of Woe, Want, and Weal," written by Isabella herself for strategic placement in one of her husband's magazines. In the following excerpt, Mrs. Beeton creates a domestic crisis for her protagonist, a young, upper-middle class wife named Augusta:

Charles was to come home by the 5.20 train from town, and at six o'clock there was to be ready

THE DINNER!

That was the bête noir — that was the skeleton in her house which Augusta was contemplating with fixed eyes and miserable mien. 'Oh! The dinner, the dinner, dinner! Whatever shall I get for dinner? Whatever shall I do?' (179, qtd. in Damkjaer 1)

At a time when modern food delivery services like Skip the Dishes and Uber Eats would have been mere domestic science fiction, Augusta's desperation must have struck a chord with many readers. Fortunately for the inexperienced wife, a friend has given her a promotional brochure ("prospectus") for Mrs. Beeton's book—problem solved; domestic melodrama averted.

By disguising advertising copy as a topical allusion, Damkjaer writes,"[a]dvertising becomes, itself, a supposed source of reader pleasure, and a fetishised object in its own right" (102). Such hidden advertising, notes Damkjaer, had to be used sparingly to maintain its effectiveness in holding the reader's attention. Consequently, Beeton also used such elements as typography and headings, horizontal lines, central adjustments, different typefaces, and white space to set off an advertisement. However, for the critical reader of fiction, the discussion of Mrs. Beeton's pseudo-story is the most informative aspect of Damkjaer’s fourth chapter:

The narrative layers of experience and repeated retelling cast the story as one that is filtered through many voices, and finally through an omniscient narrator, in a way that mimics the storytelling of the realist novel: it purports to reflect women's lived experience. Narrative fiction is not only being mimicked and mocked, it also allows for a lifelike and realistic imaginary print culture, where news of new publications is spread through human networks by word of mouth. (130)

Although Damkjaer focuses on two magazines that exploited the commercial possibilities of serial fiction to ensure that readers would return each week for the latest instalment of a novella or novel, serialisation was a strategy adopted by a variety of weeklies and monthlies, including The Graphic, The Cornhill, and The Illustrated London News. With serialization, “narrative fiction was put to the use of tying the fate of the magazine into longer serial stories." (24) In these magazines, as Damkjaer notes in her fifth chapter, about how advertising was routinely enmeshed in short fiction, the hybrid was at once a short story, an advertisement, and commercial filler.

Hybridity applied to images as well. Damkjaer highlights the significance of George Bigg's placing an image of a young woman working on Young's Patent Composing Machine in the masthead of the Family Herald. The placement proclaimed the publication not merely a triumph of modern technology, but of feminine intelligence and dexterity as well: "The pianotype machine, so prominently featured in a depiction that makes it look like a reasonably sized musical instrument, might be said to represent a domestication of printing. The masthead illustration linked traditionally middle-class skills such as playing the pianoforte with the endeavours of print culture" (134). The illustration also underscores the significance of paratextual elements — not only illustrations, headings, and captions, but also references to commercially available products and juxtaposed advertisements — in the reception and interpretation of the weekly serial.

Thus, the weekly instalment of the serial provided entertainment, filler, and a vehicle for hidden advertising, functions that served “to fill out, to expand, and to incorporate the dreams of print culture itself into story form" (Damkjaer 149). The similar functions of the Bildungsroman and the magazine — in terms of intellectual and moral development, individual progress in life, and the manifold benefits of education, instruction, amusement, and employment — bring Damkjaer to the lacklustre reception of "Charles Lever's A Day's Ride, the weekly serial appearing in Dickens’ All the Year Round in September, 1860. To bolster sagging sales, Dickens adopted the unusual expedient of providing his own serial: Great Expectations would lead off every number, relegating the Lever novel to the back pages. Unapologetically Dickens wrote to his contributor, "For as long as you continue afterwards, we must go on together." By the end of November Dickens had readied his first, sensational instalment for publication even though he found the process of writing such weekly serialisations "crushing" (Forster 565).

Why then did Dickens subject himself to the furious pace of the weekly serial? He felt that he had no other other choice if he were to save the periodical's circulation, even if the resulting work of fiction was the length of A Tale of Two Cities rather than, for example, that of the weighty triple-decker Bleak House. Damkjaer notes that the very name "Dickens" in the weekly byline of Great Expectations was an assurance of quality literature. The name "Dickens" was the trusted brand that brought readers back, week after week, to All the Year Round.

In magazines, fiction could serve purposes other than entertainment

and enlightenment. Narrative organizes information around characters and

a rising action, but in such magazines as The Girl's Own Paper

it could

even offer practical tips on interior decoration, capitalising on the

notion that readers were more than consumers of the magazine. "Samuel

Pickwick's appearance in Master Humphrey's Clock (1840-1) is not exactly

product placement," Damkjaer writes, "but it engages uncomfortably with

the commercial status of print culture" (25). It certainly represents

the editor's desire to harness Pickwick's residual celebrity, assuring

the reader that Master Humphrey's project is advancing favourably, and

that he—that is, both Dickens and his reclusive persona, Master

Humphrey—will be able to incorporate other narrative voices, including

those of Pickwick, Sam, and Tony Weller, into the weekly's pages.

Right: Phiz's farewell plate for the lengthy series: The Deserted Chamber, Vol. III, 318, in Master Humphrey's Clock (4 December 1841): — "Master Humphrey's Clock has stopped forever."

In fact, that multi-voiced project was failing, as other writers were not joining the enterprise, which then became a vehicle for two of Dickens's full-length novels, The Old Curiosity Shop and Barnaby Rudge. With the original multi-voiced story-telling scheme unrealised, and despite the celebrated visitor's offering "Mr. Pickwick's Tale," Dickens wound up the Clock in Number 86 (4 December 1841) with Master Humphrey's swan song, "The Deaf Gentleman from His Own Apartment."

What, then, are we to make of the narrative fiction presented in many popular early Victorian periodicals? As Damkjaer notes in her conclusion, rising literacy rates made this new commodity form economically viable. If the stories were often combined with advertising or advice, they also "attempt[ed] to narrativize and organize an informational medium" (197). Therefore, much of what appeared in the popular magazines, as distinct from high-brow periodicals such as The Cornhill, emanated from "the pressurized environment of serialized print" (197). Editors such as Beeton honestly believed that their readers would be delighted by these hybrid texts, which were never quite storytelling and were often advertising thinly disguised as fiction or personal advice.

Links to Related Material

- Phiz's Mr. Pickwick introduces himself to Master Humphrey in Master Humphrey's Clock (18 April 1840)

- The Economic Context of Dicken's Great Expectations

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

[book under review] Damkjaer, Maria. Fiction on the Page in Nineteenth-Century Magazines. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2025.

Dickens, Charles. Master Humphrey's Clock. Illustrated by George Cattermole and Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). London: Chapman and Hall, 4 April 1840 — 6 February 1841.

Forster, John. The Life of Charles Dickens, ed. J.W.T. Ley. London: Cecil Palmer, 1928.

House, Madeline, Graham Storey, and Kathleen Tillotson, eds. The Letters of Charles Dickens. The Pilgrim Edition, Vol. 3. Oxford: Clarendon, 1974.

Created 28 April 2025