Want to know how to navigate the Victorian Web? Click here.

In transcribing the following article I have followed the invaluable text from the Hathi Trust online version. The headpiece, illuminated A, and portrait come from the original article. — George P. Landow .

N observer of manners called upon to name to-day the two things that make it most completely different from yesterday (by which I mean a tolerably recent past) might easily be conceived to mention in the first place the immensely greater conspicuity of the novel and in the second the immensely greater con spicuity of the attitude of women. He might perhaps be sup posed even to go on to add that the attitude of women is the novel, in England and America, and that these signs of the times have therefore a practical unity. The union is repre sented at any rate in the high distinction of Mrs. Humphry Ward, who is at once the author of the work of fiction that has in our hour been most widely circulated, and the most striking example of the unprecedented kind of attention which the feminine mind is now at liberty to excite. Her position is one which certainly ought to soothe a myriad discontents, to show the superfluity of innumerable agitations. No agitation, on the platform, or in the newspaper, no demand for a political revolution, ever achieved anything like the publicity or roused anything like the emotion of the earnest attempt of this quiet English lady to tell an interesting story, to present an imaginary case. Robert Elsmere, in the course of a few weeks, put her name in the mouths of the immeasurable English-reading multitude. The book was not merely an extraordinarily successful novel; it was, as reflected in contemporary conversation, a momentous public event.

No example could be more interesting of the way in which women, after prevailing for so many ages in our private history, have begun to be unchallenged contributors to our public. Very surely and not at all slowly the effective feminine voice makes its ingenious hum the very ground-tone of the uproar in which the conditions of its interference are discussed. So many presumptions against this interference have fallen to the ground, that it is difficult to say which of them practically remain. In England to—day, and in the United States, no one thinks of asking whether or no a book be by a woman, so completely has the tradition of the difference of dignity between the sorts been lost. In France the tradition flourishes, but literature in France has a different perspective and another air. Among ourselves, I hasten to add, and without in the least undertaking to go into the question of the gain to literature of the change, the position achieved by the sex formerly overshadowed has been a well-fought battle, in which that sex has again and again returned to the charge. In other words, if women take up (in fiction for instance) an equal room in the public eye, it is because they have been remarkably clever. They have carried the defences line by line, and they may justly pretend that they have at last made the English novel speak their language. The history of this achievement will not be completely written, of course, unless a chapter be devoted to the resistance of the men. It would probably then come out that there was a possible form of resistance of the value of which the men were unconscious — a fact that indeed only proves their predestined weakness.

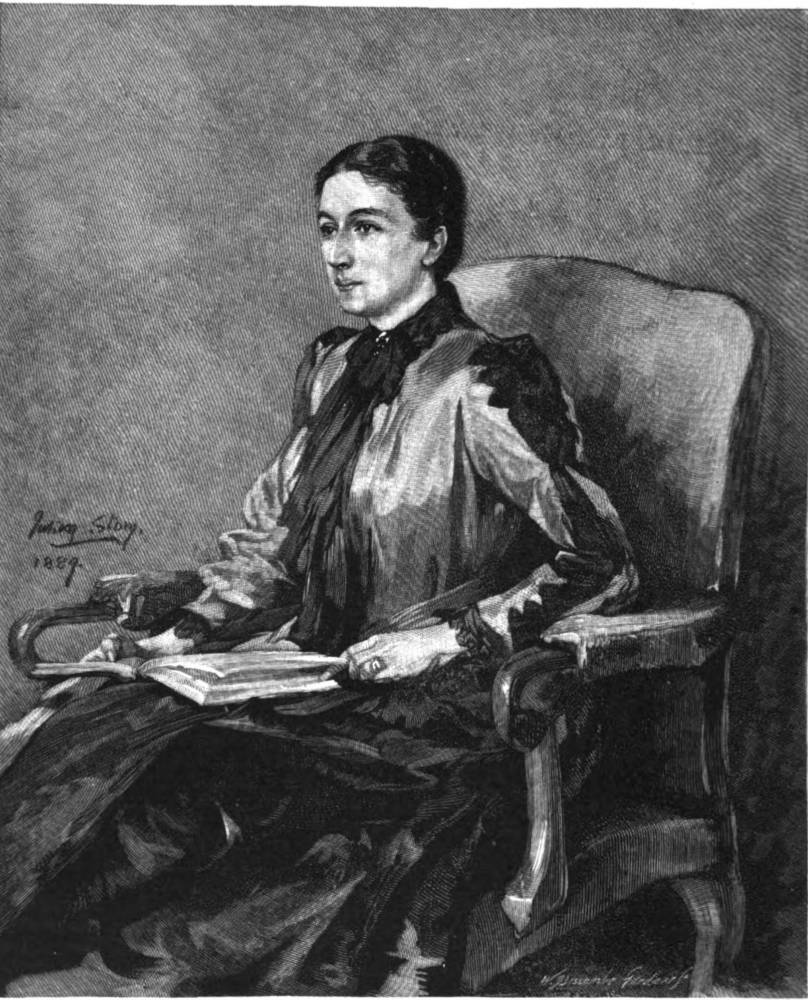

Mary Augusta Ward (Mrs. Humphry Ward). Engraved by W. Biscombe Gardner after a picture by Julian Story. Click on image to enlarge it.

This weakness finds itself confronted with the circumstance that the most serious,the most deliberate and most comprehensive attempt made in England, in this later time, to hold the mirror of prose fiction up to life has not been made by one of the hitherto happier gentry. There may have been works, in this line, of greater genius, of a spirit more instinctive and inevitable, but I am at a loss to name one of an intenser intellectual purpose. It is impossible to read Robert Elsmere without feeling it to be an exceedingly matured conception, and it is difficult to attach the idea of conception at all to most of the other novels of the hour; so almost invariably do they seem to have come into the world only at the hour’s notice, with no pre-natal history to speak of. Remarkably interesting is the light that Mrs. Ward’s celebrated study throws upon the expectations we are henceforth entitled to form of the critical faculty in women. The whole complicated picture is a slow, expansive evocation, bathed in the air of reflection, infinitely thought out and constructed, not a flash of perception nor an arrested impression. It suggests the image of a large, slow moving, slightly old-fashioned ship, buoyant enough and well out of water, but with a close-packed cargo in every inch of stowage-room. One feels that the author has set afloat in it a complete treasure of intellectual and moral experience, the memory of all her contacts and phases, all her speculations and studies.

Of the ground covered by this broad—based story the largest part, I scarcely need mention, is the ground of religion, the ground on which it is reputed to be most easy to create a reverberation in the Anglo—Saxon world. “Easy,” here is evidently easily said, and it must be noted that the greatest reverberation has been the product of the greatest talent. It is difficult to associate Robert Elsmere with any effect cheaply produced. The habit of theological inquiry (if indeed the term inquiry may be applied to that which partakes of the nature rather of answer than of question) has long been rooted in the English—speaking race; but Mrs. Ward’ s novel would not have had so great a fortune had she not wrought into it other bribes than this. She gave it, indeed, the general quality of charm, and she accomplished the feat, unique, so far as I remember, in the long and usually dreary annals of the novel with a purpose, of carrying out her purpose without spoiling her novel. The charm that was so much wind in the sails of her book was a combination of many things, but it was an element in which culture — using the term in its largest sense—had perhaps most to say. Knowledge, curiosity, acuteness, a critical faculty remarkable in itself and very highly trained. The direct observation of life and the study of history, strike the reader of Robert Elsmere — rich and representative as it is — as so many strong savours in a fine moral ripeness, a genial much—seeing wisdom. Life, for Mrs. Humphry Ward, as the subject of a large canvas, means predominantly the life of the thinking, the life of the sentient creature, whose chronicler, at the present hour, so little is he in fashion, it has been almost an originality on her part to become. The novelist is often reminded that he must put before us an action; but it is, after all, a question of terms. There are actions and actions, and Mrs. Ward was capable of recognizing possibilities of palpitation without number in that of her hero’s passionate conscience, that of his restless faith. Just so in her admirable appreciation of the strange and fascinating Amiel, she found in his throbbing stillness a quantity of life that she would not have found in a snapping of pistols.

This attitude is full of further assurance; it gives us a grateful faith in the independence of view of the new work which she is believed lately to have brought to completion, and as to which the most absorbed of her former readers will wish her no diminution of the skill that excited on behalf of adventurers and situations essentially spiritual, the suspense and curiosity that they had supposed themselves to reserve for mysteries and solutions on quite another plane. There are several considerations that make Mrs. Ward’ s next study of acute contemporary states as impatiently awaited as the birth of an heir to great possessions; but not the least of them is the supreme example its fortune, be it greater or smaller, will offer of the spell wrought to—day by the wonderful art of fiction. Could there be a greater proof at the same time of that silent conquest that I began by speaking of, the way in which, pen in hand, the accomplished sedentary woman has come to represent, with an authority widely recognized, the multitudinous, much—entangled human scene? I must in conscience add that it has not yet often been given to her to do so with the number of sorts of distinction, the educated insight, the comprehensive ardour of Mrs. Humphry Ward.

H. J.

Related Material

Bibliography

James, Henry. “Mrs. Humphry Ward.” The English Illustrated Magazine. 9 (1891-92): 399-401. Hathi Trust version of a copy in the University of California Library. Web. 21 August 2021.

Last modified 21 August 2021