Want to know how to navigate the Victorian Web? Click here.

“We're going down hopping to-morrow,

To leave our poor homes and their sorrow.

And what we can’t pick we must borrow.

Down by the sweet gardens of Kent

We went.

They pay but eight bushels a shilling,

And bins take a dozen a-filling.

How can us poor folk get a living ?

Down—by the sweet gardens of Kent

We went.

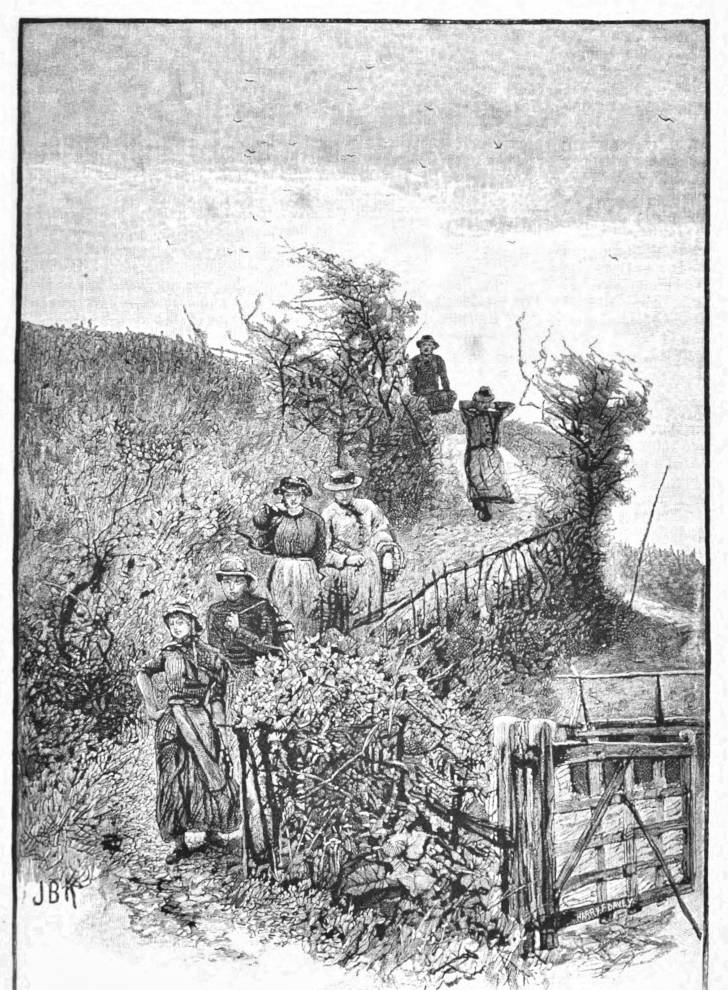

Such is the rough and halting rhyme, varying with the changing conditions of each year, and set to a monotonous tune with an octave jump at the end, which may be heard along Kentish and Sussex lanes as September draws near, bringing with it a strange crowd of men and women from the lowest slums of the metropolis as well as from the healthier confinement of provincial towns, who come to breathe the pure air of country meadows while they earn a merry shilling over the fragrant bins of the hop-growers. A strange crowd they are indeed !

Ragged tramps who never earn a penny at any other time of the year, and who spend what they earn now, as fast as they earn it, in drink; brutal men who beat their wives openly in the fields just as much as secretly behind the hedges, or in the huts where they sleep at night; sickly women and children bred in city alleys, who often take to the occupation soley because it is their own means of having the change of air prescribed by their doctor; and on the other hand, hale and heart men of the country smart servant girls who take this opportunity to be out of place that they may have a merry time of it; weatherworn mothers of the neighbourhood with the whole family at their heels, from the boys and girls who can pick their bushel or two themselves to the baby who cannot be left at home; handsome youths and maidens from the villages around, or from other villages whence they have earned their way— maidens whose bronzed faces and well-worn clothes accord far better than anything with the surroundings, rough of manner, and rough in speech, but perhaps not any the worse for that, and whose merry laughter rings out over the fields and lanes, till it even drowns the coarse taunts and coarser oaths of the less reputable portion of the comunity.

Ever since the winter the thoughts of all these people have been turned, more or less, to the hop-picking.

The ne’er-do-weels have made it their excuse for earning nothing during the whole remainder of the year; the heads of families have looked forward to it as the means of satisfying long-standing claims; mothers have seen in it the chance of little comforts for the coming winter, of warm garments and new frocks for little growing forms, of a savings’-box against bad times, and every one has watched the growth of the crop, and discussed its prospects with almost as much anxiety as the grower himself, to whom its failure has been known to mean even ruin.

Ever since the stagnant winter-time was over, when the ground was covered with snow, or crusted with frost, or at best showed no more remembrance of its brilliant harvesttime than the cone-shaped stacks of hop-poles set at regular intervals over the barren earth, like huts of some deserted village, and around which the blue eyed speedwell, the white-starred chickweed, and the purple nettle clustered in the cold sunshine as heralds of the coming spring—ever since the early days of March when the purple-red shoots made their way above ground, have the farmer’s anxieties begun. Although not until after the time when the women and unemployed of the villages have earned their first-fruits of the hop-gardens by tying up the early shoots to the poles, are the worst evils to be looked for, still the attention of the farmer must be constantly on the alert, and many and curious are the manures tried to enrich the growth of the plants and to avoid the after perils of the “ fly ” and the “ mould ” which have been known to spoil so many crops that promised brilliantly in their earlier stages.

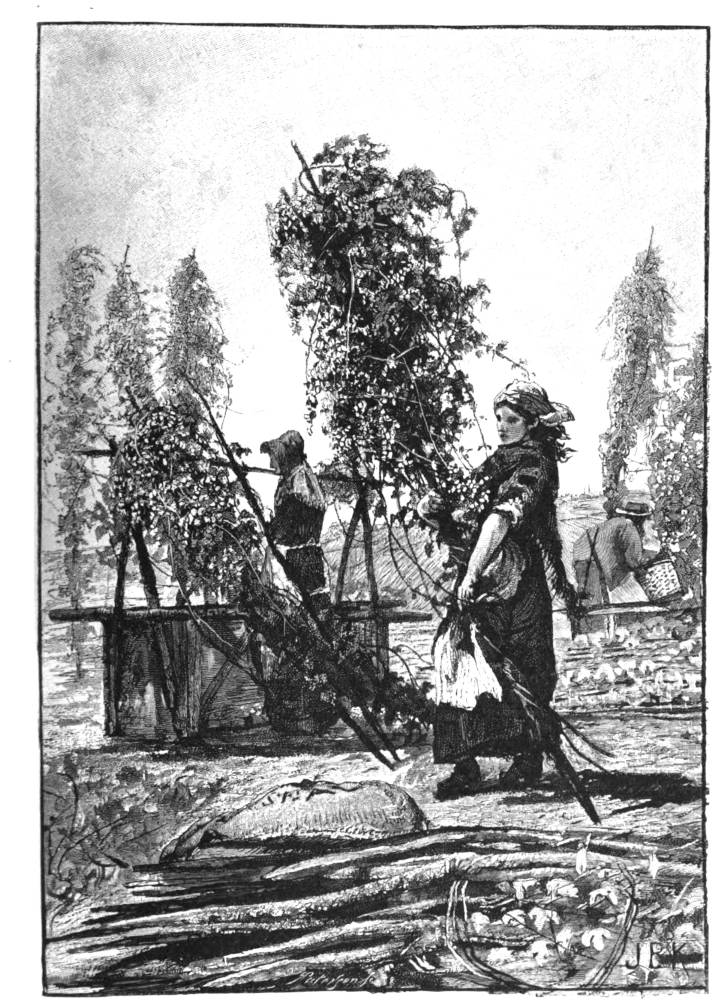

Although of course not equal to the luxuriant beauty of their autumnal perfection, the hop-gardens are a pretty sight in the flowering spring-time, with the woods and fields and orchards, budding or a bloom all around them, and the women standing in their midst tying up the main “ bines” with thin matting or rushes, so that they may coil upward of themselves around the poles with that tenacious grasp of which the hop is specially capable, and throw out the side shoots that form the waving crests and the twining tendrils so graceful at the full growth of the plant.

All through the year the progress of the hops is food for comment and speculation to the country-folk. Everybody knows what kind of a crop each farmer is likely to have, and what kind of a “ tally” he is likely to pay. A “tally” means the price paid for picking per bushel. It varies according to , the season; a good crop is picked faster than a bad one, and large hops fill the bins; quicker. Two shillings and sixpence per dozen bushels is first-rate pay, but the tally 3 is often not over eighteenpence per dozen,

A “professional picker” who works from dawn to twilight, and not, as some of the village folk, who arrive late on the field, can however, easily pick eighteen bushels a day, and a rapid worker picks nearly two dozen bushels, so that a woman—and even a man —earns a fair day’s wage, and where a family of five or six are in the field together, no mean sum may be put into the savings’-box at the end of the week.

How eagerly do the poor folk watch the weather as the “hopping” season approaches! The first fortnight of the month is comparatively safe unless the luck be sorely against , them, but where the farmer is a large grower , even his own crop will not be picked in less than three weeks, sometimes not in less than four weeks, and the vagrant portion of the community often pass from one farm to another according as the crop ripens.

For a good many among the Kent and Sussex farmers, desirous apparently of getting their crop into the market earlier than their neighbours, seem to have taken during the last twenty years to growing a kind of hop called the “Early Prolific,” which, in the opinion of some men of long experience, does not possess the aroma of the “Golding” or; “Jones” hop, and not being of the same value to the brewer, does not command the same price. Until lately the “Early Prolific” seems to have passed muster in foreign markets, but now its inferior power is being found out even there, and growers of it are contemplating “grubbing up” their plantations after the present season, and resetting them with the older varieties. At present, I however, there are still many plantations of “Early Prolifics” which come to maturity a week or two sooner than the other kinds, and if the pickers make their arrangements well, they can generally secure one or two “jobs” out of the season. It is probably in the Sussex district that those interested s in the hop-harvest watch the weather the most anxiously. The most harmful kind of storms are less to be feared on the inland plains and hill-sides and in the wind-screened valleys of Kent, than where sea-breezes sweep across the Sussex downs, finding access even to the favoured slopes, which the farmer has chosen as the most sheltered and open to the sun.

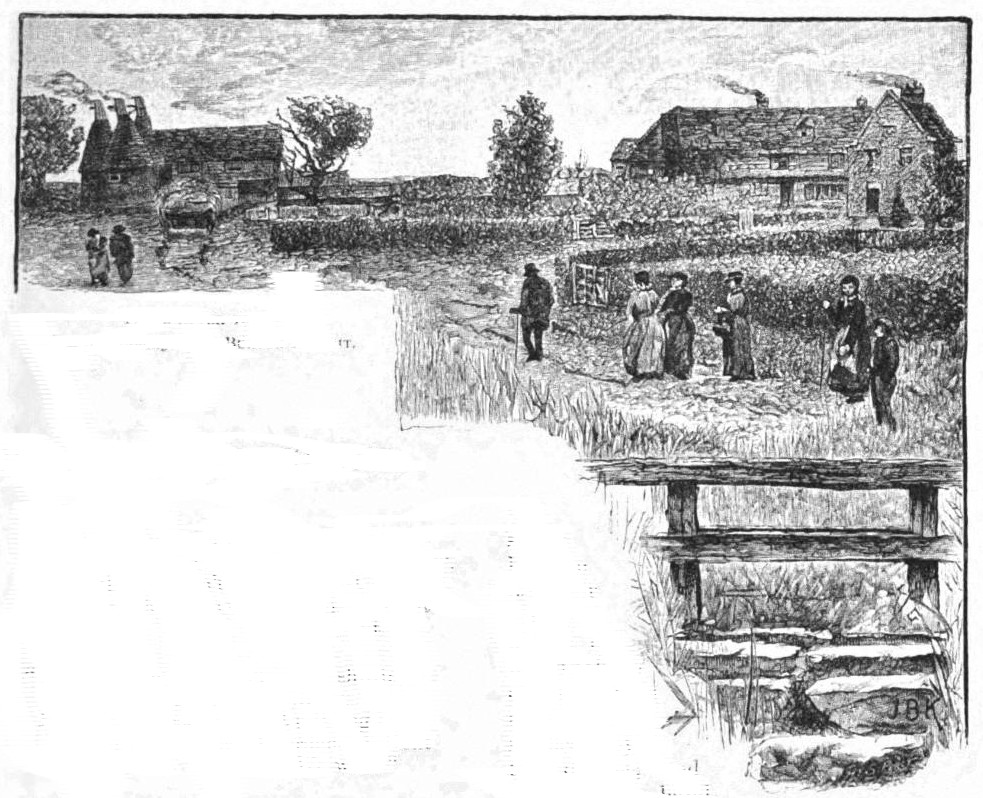

The Beginning of the Day by J. Buxton Knight, whose initials are seen at left. Click on image to enlarge it.

Mere rain does not seem to be feared as it is feared at the hay-making or for the wheat harvest. So long as the pickers will pick the farmer minds the rain but little.

But as the pickers are in such a great proportion of women and children, rain does materially affect the attendance in the field, and is dreaded by the unfortunate “hopper,” who must either risk cold and fever or forego the sorely needed day’s wage, as well as in a measure by the farmer who sees the work retarded.

Rain, however, is not the worst that the weather can do to the farmer. Granted that he has come safely through the perils of the “fly” and the “mould,” which result from unhealthiness at the root rather than from any external influence, and which, moreover, would have shown themselves earlier, he has still to fear the “browning” of his hops by a severe gale of wind. And this, as well as another evil, the Sussex farmer has more cause to look for than his Kentish neighbour. A gale at this season, when the plants are towering high and laden with fruit, will often lay low whole acres of hop-fields, or turn the berry brown and useless even when it does not cast it to the earth; and on the other hand, if the weather be unusually hot and still for the time of year, sea fogs will sometimes creep up across the marshes, or land mists steam out of the moist earth, which dykes and streams intersect, and steal over the plantations at dead of night after the hot days. On the morrow the sun rising brilliant and fierce again, scalds the moistened plants, and turns the husks of that dead brown colour which the hop-grower curses as he sees, for it means that he will have to leave whole acres to rot, the cost of picking and drying not being worth any return he could hope to get.

Many a sleepless night must the weather-wise farmer spend.

When the moon rises over the lonely plain and folks wander forth to revel in the cool after the hot and sultry day, he walks the marsh, watching the mists rise, blue and faint, in streaks and sheets over the level land, and counts their cost to him when they shall have floated upward and over to the sheltered slopes that he thought secure. And when the dangers of heat are over, still he lies awake at night knowing that the cruel equinoctial gales are just about due at this time, and listens to every puff of wind. And too surely maybe he hears it rising and sighing across the marsh, hears perhaps even the distant roar of the waves thundering upon the beach a mile and more away, and knows that the lashing gusts are tearing up the clefts of the downs, levelling whole stretches of precious garden, where yesterday the beautiful vines towered ten and twelve feet high, waving their clustered crests in the fragrant autumn air, intertwining their graceful tendrils from pole to pole, drooping their bunches of downy fruit, in cascades of palest green amid the luxuriant wealth of vine-shaped leaves that drape their stately height.

Many a fortune has been made and lost over hops, many a field that brought in hundreds of pounds one year will scarcely pay for its cultivation the next! It is no wonder that the farmers have an anxious time of it, and stand morosely at eveningtime on the crests of the downs where the windmills are placed to catch the western breezes and watch the sky when the sun goes down.

Strange and lurid skies they are sometimes at this season, pillars upon pillars, and masses upon masses of grey cloud piled away above the horizon, or swooping dowm towards it, lightening and softening overhead into tender dove-coloured tints where a clearer blue is seen dimly athwrart them. And beneath the clouds a fiery space of angry crimson, of whose flames they seem to be but the dense columns of smoke, and whose redness grows in intensity till it is reflected upon all around—reflected in pearly pinkness upon the clouds overhead, and upon the clouds to the east, in golden mellowness upon the moon rising out of the sea, in amethyst tints upon the grey vapours to seaward and upon the stream that winders across the dim marshland, in purple haze upon the distant downs or where the oast-houses writh their cowled heads stand out upon the nearer ridges. Glorious sunsets for the artist, but ominous to the farmer.

Fortunately however for the land, hop seasons are not always bad, nor farmers’ prospects always at the lowest ebb. The sun sets red and clear many a golden September evening behind the blue downs that lie beyond those lonely meadows of the Sussex marshes, and rises clear and regal out of the dark sea, till it awakens it all into jewelled colour beside the brown of the mellowing pasture-land. The days are warm, but the sun’s power is tempered, and sucks no dangerous mists out of the earth. And on the tender evenings of these autumn days, when the gentle heat has been drawing the fragrance from the pine-trees up in the lanes, and the powerful aroma from the hops, till one would almost think the people must be overcome by the heavy scent, voices are mern as the pickers stand over the great wooden framed canvas bins divided down the middle into two parts, and try to calculate how many bushels they have picked during the day, before the overseer comes round to weigh out the contents and write the quantity down in each one's little book. For the old fashion of small medals for each bushel and large medals for each twelve bushels has gone out now that methods are simplified.

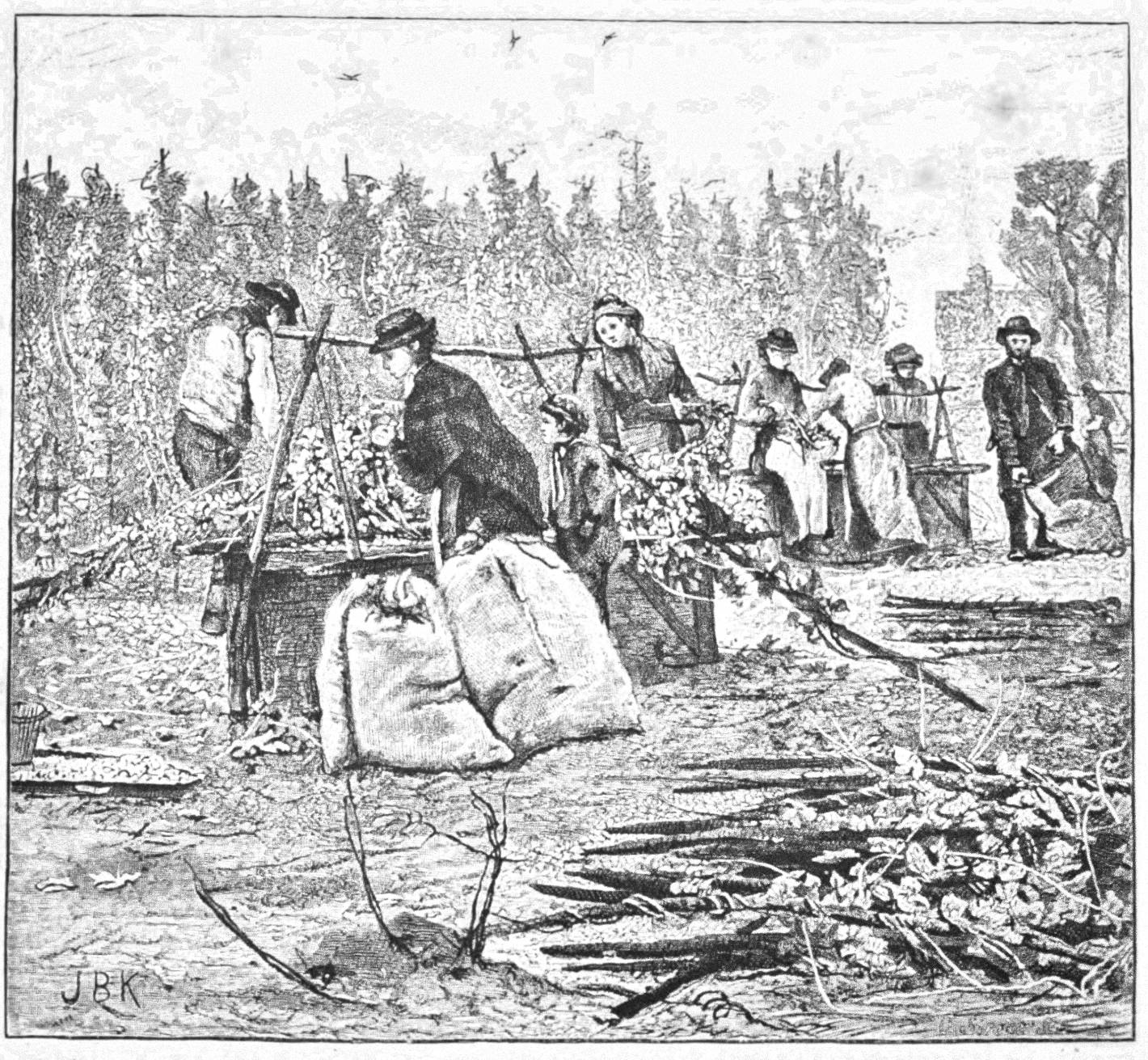

Since early morning, with only an interval for the noontide meal, the pickers have been busy. Neat and homely, smart and tawdry tattered and picturesque, there are costume* of every kind and positions of every sort Some stand to their work, some sit upon the edges of the bins, half shrouded by the shower of green from the richly-laden hop pole, which rests aslant against the wooden edge. Some stoop, plucking at the lower clusters, some stretch out their arms to react the highest, some, who are children, stand upon the framework that they may react further. There one little two-year-old baby has climbed so well that he would have fallen over into the fragrant mass had not his mother clutched angrily at his plump little legs. Here an old woman in a ragged old fashioned shawl with a huge blue shade upon her bonnet such as bathing-women used to wear, picks silently and steadily, bowed and stooping over the bin which she shares with a giddy young girl from the village, who throws handfuls of leaves in with the hops, and only remarks laughingly that “it all counts in the measuring up.” Here a frail young woman, who has been recommended to try the smell of the hops for a chest complaint, sinks down wearily on the ground for “a bit of a rest” till the overseer comes round again; there a light-hearted fair-haired girl, with locks curling as the hop-tendrils themselves, and floating in the breeze as they do, pulls at the same hop-pole with a gay, bold youth, whose black eyes sparkle as he singg a snatch of some country song; here a mother sits down to suckle an infant, while the father tucks up an older child for a sleep under the arching green.

Behind them lies the bare uneven earth, strewn with hop-poles and broken tendrils in wild disorder, before them stretches the luxuriant plantation where the crop is yet ungathered. And when the farm labourers told off for the purpose have pulled up the last hop-pole for the day, and borne it, weighed down with leaves and fruit, to the bins where the pickers await it, then the cry of “No more poles” that has already resounded at midday for dinner, fills the air once more, and the workers begin to make ready for the homeward start.

The mothers who are of the villages of the neighbourhood gather together the toddling children, and settle afresh the baby who has lain all day long sleeping under the scent of the hops, sheltered from the sun by the big blue shade over its cradle, the lasses tie on their straw hats, or their print sun bonnets afresh, and tidy up the remains of their dinners in baskets, the men light their pipes, the old women wrap their faded shawls about them—for appearance this time, and not for warmth—and all wend their way once more up the hills and lanes to their homes. The elders are comparatively silent, they have more than enough to do “ minding ” children, and thinking of home-cares and what the wages in their pockets will do towards meeting them; but the girls and lads get together in knots, laughing and joking, discussing their earnings and whether it is better to have them or to spend them, discussing also the looks and ways of the “foreigners” in the field—as all those are called who are more or less vagrants, or at all events, dwellers in the camp below the hill, where the farmer has provided straw huts for those who have no homes in the neighbourhood.

It is in this camp that the most picturesque scenes of the “hopping” are to be seen. In a stubble field under the lea of the hill upon whose crest stands the old stone farm-house shaded by tall ash-trees, and setting its gabled end towards the distant sea, the farmer has erected a little village of cone-shaped straw huts into which are crowded a curious medley of men, women, and children of various callings, stations, and even nationalities.

In the front of the camp, before a hut of somewhat larger proportions than some of those about, an old man, with grey imperial and moustache, sits cross-legged, holding a child on his knee and ordering a young girl about in a voice which bears unmistakably the French accent.

Here is a “foreigner” in truth, but apparently no outcast. The handsome old man seems quite able to jest and to hold his own with the best of them, nor has his daughter allowed herself to be the last to get her pails filled at the great water-butt which the farmer has driven into the middle of the field for the supply of the people.

Hop-Pickers at the Bins by J. Buxton Knight, whose are lower left corner. Click on image to enlarge it.

The after-glow is beginning to fade by this time, and the first vividness of colour is slowly dying away from clouds and hills and stream; in the dim light the fires of the camp strike a lurid brightness into the dusk, and in another settlement upon a distant hill—a camp where the habitations are only canvas tents, not solid straw huts as here—the spots of light flash out in the deepening darkness with even greater brilliancy than where they are close at hand. At the door of a hut at the opposite extreme of the camp from that where the old Frenchman lives, a tall slim girl stands up in the twilight watching the sticks, which she has just thrown upon her fire, slowly catch alight and crackle into a blaze. Above the tire hangs a kettle suspended on a horizontal hop-pole supported by two tripods, and the girl stands with a stick in her hand to stir the embers when the blaze shall begin to die out.

Her clear-cut profile, and her little head with the smooth bands of dark hair are detached upon the luminous sky. She is “pretty Jane,” the rustic beauty of the vagrant camp. She has only clumsy, worn-out shoes to her feet, and her faded purple gown hangs loosely upon her slender young shape, and has, moreover, a great rent under the arm and a square patch at the knees— but what of that!

She is “pretty Jane” all the same, and the old woman—her mother—is quite right when she says presently, stooping to pick up a two-year old babe who lias placidly fallen into the fresh-water pail, “Come now, child, look alive and get to the village for the ale, or it’ll be pitch dark before you get back, and who’s to tell what might happen to you? ”

Jane takes the pitcher and strides off across the stubble field and up the hill and truly enough the darkness soon begins to fall, and even the camp fires die out one by one as the cooked and eaten, and the weary “hoppers” turn in to rest. to rest.

A Fruitful Year.

This is the early part of September; more weeks of it and then all the hops that can be saved will be picked and in the kilns, and the village will have returned to its former steady monotony.

Already cart-loads of sacks have been making their way up the hill to the red-coned coast-houses, whose white cowls peep behind the pine-trees. The kilns have been well filled- — too well filled perhaps for the complete satisfaction of the farmer, or of the gangs of men and women eager for more work. For when the hops are picked faster than they can he dried, the picking must needs he stopped, however precarious he the weather, until the kilns are emptying, or the fruit would spoil while waiting.

The fullest grown, least shattered, brightest hued and best dried hops are always those which command the highest price at market, and a good farmer spares no pains to achieve each of these ends, and always looks more to the quality than to the quantity of his crop. Hence only men of great experience are employed in the drying process, which is one of the most important for the perfection of the hop. These men remain in the kilns day and night keeping the fires alight, and turning over the hops so that they should not burn.

The charcoal fires burn in small brick stoves—six or eight to every kiln—on the ground floor of the oast-house. The stoves are inclosed in closely cemented chambers, and at a distance of about eight feet above these the open lathes are laid, with coarse loose-meshed hair material strained over them, upon which the hops are spread—a few inches thick—to dry. A mixture of charcoal and anthracite coal is burned in the stoves, so that after the first lighting there is no smoke, and as the fires are kept bright and clear night and day at a certain temperature, the hops dry gradually by means of the pure hot air ascending from the inclosed chambers below.

The heat in the hot chambers where the men have to attend to the fires is terribly oppressive, and there is a curious odour from the brimstone which some growers have thrown upon the embers to give the hops a yellow colour—although some others again prefer the greenish hue which they would naturally retain.

The loads come in night and morning, and take eleven hours drying, so that two hours in the twenty-four is allowed for sweeping up the dry hops and spreading the fresh ones. An ordinary kiln dries about five hundred bushels at a time, and as these simmer above the hot air a moisture rises from them so dense that a man can often not see his neighbour at work; the fragrance is then so powerful that were it not for the cowls open to the fresh air in the roof, the men would probably be overcome by it.

“If a man be just right it’ll do him a power of good,” the people say, “ but if he ain’t just right it’ll turn him over.”

After they are dried, the hops are pressed into huge sacks, or “ pockets,” by means of a round iron weight forced down into the sacks by a windlass. This used to be done by a man who stood in the “ pocket ” and stamped upon them as they were shovelled in over his head, but all these simple means are giving way to machinery nowadays, just as the sound of the flail is no longer heard in the land at threshing-time, and the wine press is no longer trod by the youths and maidens of southern villages.

And so gradually September wears away and the hops are gathered and garnered and stored.

Together with other old things the old custom of a hop-picker’s supper has died out, and the roofs of the oast-houses and barns no longer resound to the clanging of pewter mugs, the singing of wild choruses and rough songs, the tuning and scraping of fiddles, the treading of heavy feet upon wooden boards. But the men no doubt find their own means of making merry with the village maidens nevertheless, and the storms which so often shadow the threshold of autumn until the crisper weather be fairly established, trouble the hop-pickers no more than, it is to be hoped, they trouble the farmer now that his crop is gathered and safe.

Fairy mists may drape the marsh at even-tide and hang over the quiet dykes, lurid sunsets may bathe the bosom of the downs in ominous purple tints, soft clouds may hurry fold upon fold and wreath upon wreath of grey vapour over the sky, billows may thunder afar upon the beach, and blue waves grow black in the bleak air, and storm-winds tear across the level land to burst their fury against the hill, but lads and lasses used to an out-door life take small account of such trifles, and no doubt find their own means of amusement whether days be dark or no.

The labourer at his plough is a lonely individual, and fits sol)erly into the sober background of quiet tints and mournful landscape, but ho|>-pioking may almost be called the recreation of labour, and, the laxly scarcely more than languid from the gentle fatigue, the mind exhilarated by the unwonted day-time companionship, it is not difficult to understand why the “hopper” should be considered the most, genial of his class, and “hopping” season the most cheerful time of the agricultural year.

Bibliography

Anon. “Hops and Hop-Picking.” The English Illustrated Magazine. 4 (1886-1887): 235-440; Hathi Trust version of a copy in the Pennsylvania State University Library. Web. 29 January 2021.

Last modified 22 February 2021