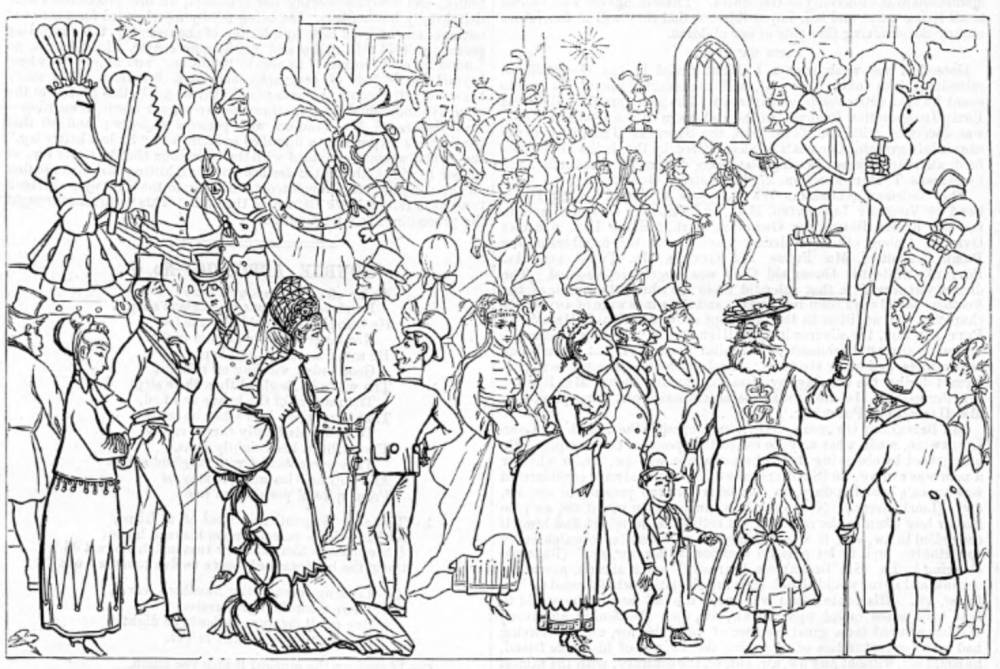

The Tower of London. From Ephraim Dodge in London to Eben Stash, New York. William S. Brunton (fl. 1859-71), artist. Fun (30 June 1868): 160. Signed with a monogram lower left. Engraved by the Dalziels. Courtesy of the Suzy Covey Comic Book Collection in the George A. Smathers Libraries, University of Florida. Click on image to enlarge it.

Details

The accompanying text

Dear Eb,—Did I predicate that Royalty in this as well as in all other unenlightened parts of the superficial universe, was a Quockerwodger? If I did, so much the worse for Royalty; for it’s everlasting true, as you’d opinionate if you went with a reflective mind to the place Mrs. D, and self have been on a visit to at the eastern confines of this bloated town.

Your free and independent blood might bile when you come to the Tower of London and found all history falsified by Queen Victoria refusing to locate there; but I guess it would go over biling point and evaporate in steam that would locomote you quick to another hemisphere when you’d paid your sixpence extra for the acquaintance of the Crown jewels and found ’em all out for shams. There may be some confiding cusses in this town that believe, but I guess I’ve seen too many precious stones to bo one of their society. No, Sir, the jewels went away when Charles II. tried to steal 'em, and ever since they've been locked up in a patent cash-box under the Throne in the dodrotted old House of Lords. That box is let into a hole in the pavement, and the key of it's double locked in a thief-and-fire-proof iron safe built into the wall behind the state bed in the best room at Windsor Castle. It wouldn't he safe in this tyrannical country for me to name where Ib got the information. Let it be enough that Mks. D. and self have been mixing pretty considerable in more society than I ever see together at one time before—and that though Albert Edward is prevented by the envenomed influences of Court etiquette from being as responsive as becomes his station. We continue to leave cards daily not only on him, but extra super-pressed samples of the same for Mrs. A. E., known in this fatuous old agglomeration of toadyism as H. R. H. the Princess Alexandra. If there’s a flavour of old Bourbon in the hair about this communication, you may just set it down to my being riled some at that dodrotted old building begun by Julius Caesar and concluded by contract, where such as hadn’t underwent tortures, was run out on to the hill in front and slicked off without their heads to another world, just in front of a screaming pile of dock warehouses and a Dutch cheese store. This, sir, was the cause of Royalty removing from the neighbourhood. The tortur’ chambers it could gloat over, the thumb-screws, and mediaeval val knuckle-dusters, the gougin’-irons and the patent collapsing ancle-crushers it could enjoy for everlasting, but the axe and tho block was too much of the slaughter-house, and took away the Royal appetite for calves’ head, which, with proper fixin’s, I do say is a diet not worse than some things I have had, if it wasn’t used for every sort of entrée by this barbarous people, that haven’t heard of hominy, green oysters, canvas-backs, gumbo, turtle steak, and other products of the land of eagle-soaring freedom and sun-staring liberty of opinion. Everthing here, sir, is calves’ head and plain eating. Them’s the grand divisions of all their solemncolly banquets and their liver-splitting festivities. Plain eating means roast beef, and saddle of mutton, and made dishes—which is the British for entrées —are, more or less, all calves’ head, lard, melted butter, toadstools, onion and chopped parsley. I’ve analysed them till I’ve boon fit to bust, and would have busted if I could havo done it conveniently, a-purpose to spoil their dinners.

Well, Sir, the crowning blow to the Tower’s being a Royal Palace was the sum-totalling of the whole of English history by O. Cromwell when he reduced Charles Rex to a fraction by cutting off a nought. That was the last execution on Tower-hill; and the Royal Person that the laughable cusses here nominate the Merry Monarch, tried to take out the cost of his board elsewhere by sending for the jewels.

O. Cromwell was too many for him, my dear Eil, as must always be the case in Democratical and Republican Institutions. He’d sent away the real stones, aud put in samples of stained window-glass and cut chandelier drops. Awful that of 0. C. I won’t deny but what the place gave Mrs. D. and self a turn. There was a ghostly old bewilderment in a baggy serge tunic and a ridiculous hat, like a black velvet foot-pan with a wreath of twopenny ribbon bows round the brim, that showed us over where the names that we read of in history was scrawled on the walls of the places they’d been solitary confined in; and what with them, and the rows of old iron-plated skunks that was drawn up in the dark passages, I do swear I ain’t felt so bad inwardly not since I was in Cincinnati at pig-curing time, and watched the critters sent to etainal smash and cured into store pork before they’d finished their grunt. I was that bad that I asked the old imbecility if he’d put himself outside of something, but he only smiled feeble, and didn’t seem thirsty, so me and Mrs. D. adjourned to a bar, and had a smile a-piece, since which I've been at home, with a box of digestive candy, studying British History. Yours, E. Hodge.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the University of Florida library and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Last modified 3 June 2018