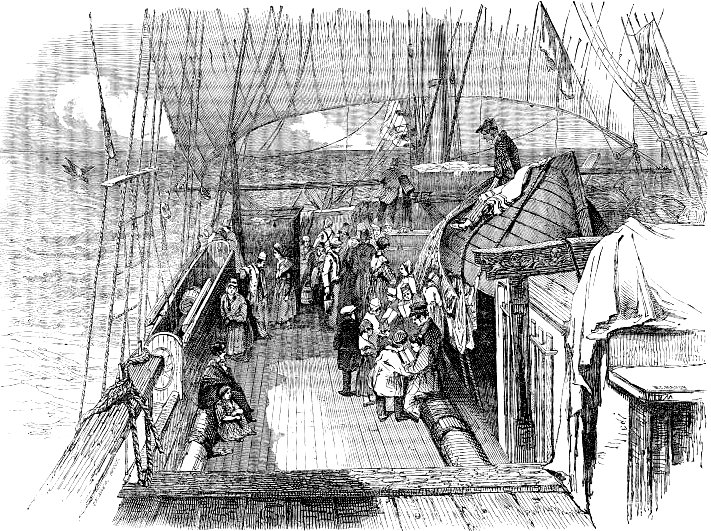

The manner in which the time on board is passed may be interesting. I think I cannot do better than refer to parts of a journal kept on my voyage out, and which at the same time will serve to explain the accompanying Engravings, from drawings made from sketches taken during the passage."

"Four bells. On deck, Weather thick and hazy. Wind W.N.W., and steady; ship going about seven knots. off Madeira: distant twenty miles. Mist gradually disperses, and the beautiful island is clearly discernable [sic], capped by the last clouds of the morning. — Six bells. A general turn-out from below. Breakfast. Emigrants on deck disperse themselves in various little groups. The schoolmaster has summoned his little class, and seated reverentially on some spars, the prescribed educational course is in full progress. A contemplative shepherd takes a solitary seat on the keel of the reversed long-boat amidships, while several anxious souls looking after creature comforts surround the cook's gallery. Not a few are lounging over the ship's side, prying with curious eyes into the secrets of the 'deep, deep sea.' 'Portuguese men-of-war,' as Jack contemptuously calls a beautiful mollusk, common to these latitudes, pass by in hundreds, presenting to the wind their gossamer-like sails, tinted with the most beautiful pink and lilac. Flying-fish have ceased to be the 'lions': they were on [40/41] first acquaintance. They rise in shoals from the mater in all directions, and after a short hurried flight, drop with extended splash into their element again.

Four drawings by Skinner Prout — from left to right: Emigrants on Deck. "Tea Water!" Soup Time. Dinner in the Forecastle

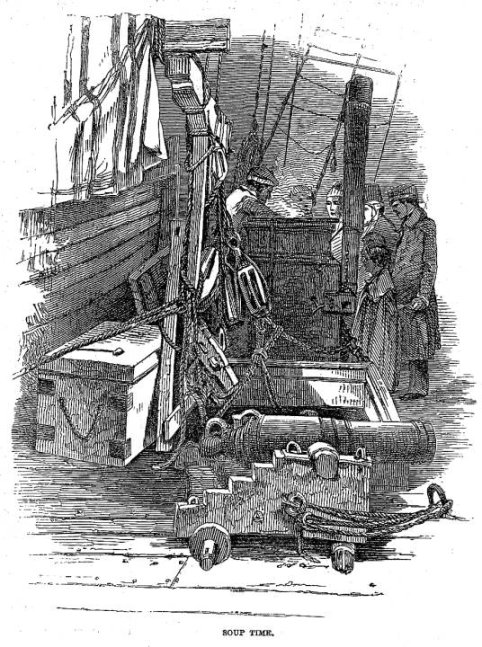

"The sun is now fast approaching the meridian, and some little bustle is observed on the quarter-deck. The captain, two of the mates, the doctor, and a tiny midshipman, have all adjusted their several sextants and quadrants, and are making a steady examination of the horizon immediately to the south. gradually a long string of passengers ascend from the cabin, and curious middle-class emigrants gather in the rear of the astronomical party, who are, in fact, engaged in taking the sun's altitude, to determine our present latitude. After some minutes, the instruments are lowered within a few seconds of each other; and the Captain, solemnly addressing the first mate, says, 'Mr. Jones, make it noon.' 'Ay, ay, sir. Forrard there; strike eight bells.' This important business settled, conversation then becomes general, and turns upon what southing the ship has made in the course of the last 24 hours. For the next hour, many and anxious too are the enquiries at the cook's gallery; whilst the ship's company gather round a huge tub, with like devotion, narrowly inspecting, in the first place, the steward's integrity as regards mixing the grog; and, in the next, disposing of their allowances, each in his own way — some making short work of it upon the spot; others, in cans or bottles, carrying it away to reserve for future enjoyment. — Two bells. Dinner is now announced, and the hatchways fore and aft are pouring out a stream of hungry mortals. It is pea-soup day, and the cook, almost lost in the dense and savoury atmosphere of steam which rises from the coppers, is ministering to the creature wants of the attendant crowd, who, with hook-pot or pannikin in hand, are patiently waiting their turn. According to the rules and arrangements of the ship, the emigrants are divided into lots, or messes, of six or eight persons in each; and, except in the varying nature of the provisions, the incidents of the daily dinner on board partake very much of the same character.

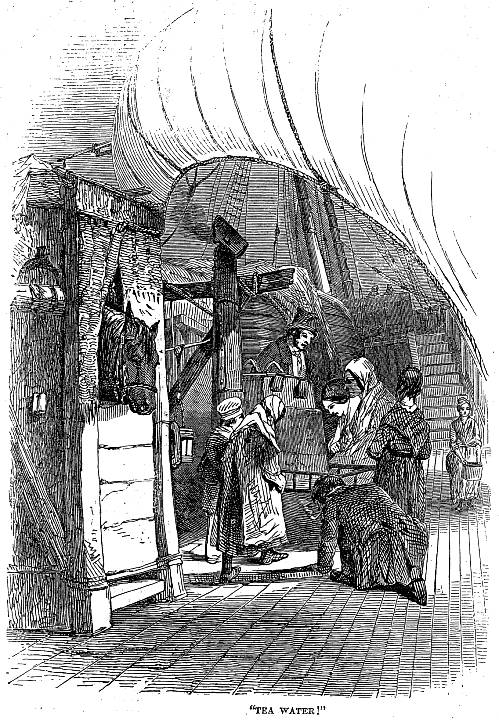

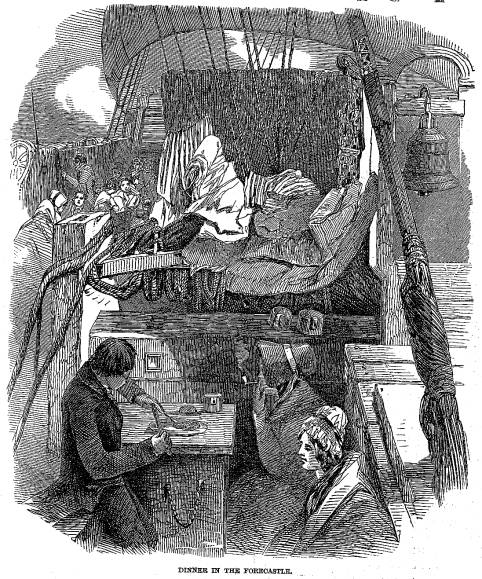

Sometimes, however, the forecastle (or fox'cle, as it is always called), an elevated platform in the bows of the vessel, is chosen for a select dinner-party, who, in the fresh, open air, enjoy their meal in true pic-nic style. Tobacco is no the order of the day — the silent indulging in a pipe, the talkative enjoying a cigar — whilst all are happy. What cares, in fact, can arise in the bosom of the wide expanse of ocean? The griefs we brought with us are forgotten, whilst all vexations have been left behind. Sleep too, comes almost naturally to minds so situated. Thought becomes a burden where there is so little to excite it in providing for the wants of the body; therefore it is that, the pipe finished, the afternoon's nap is a retreat to which emigrants on the passage out generally retire until near tea-time, or near six bells, when the cook is again at his post — the cry of 'Tea-water!' penetrates the depths below, and soon, in noisy response, clattering hook-pans, pannikins, and pans are again rushing up the hatchways, and crowding around the galley.

"On board the good ship the Hope, after tea, two religious services were performed, at least, the Catholics selecting one of their party, who always read prayers; whilst to the rest of the emigrants the surgeon, as usual in such vessels, read the service of the day as set forth in the [Church of England's] Book of Common Prayer. Eight bells struck, and another transition of thought varied the proceedings of the day. Forward are preparations being made for a dance, and a musical Jack is soon found, who, seated on a coil of rope, or perched on a spar, in a very short time is plying most vigorously the fun-in-spring fiddle. In the confined space of a ship's deck polkas and quadrilles are out of the question, though at first much affectedly fastidious disinclination is expressed against the reel and the jig. But it is not long before these last reign triumphant, and delicate forms and choice spirits foot the monotonous but merry-going measure with as much enjoyment as if they moved in a minuet before hundreds of observant eyes. Now, for one moment turn our eyes from the mirth-stirred bustling scene on deck, and scan the wide solitude of the surrounding ocean lit up by a splendid moon; not a sail in sight save the white swelling canvas over our head, bending bravely before a spanking breeze that is steadily urging us on in our trackless way.

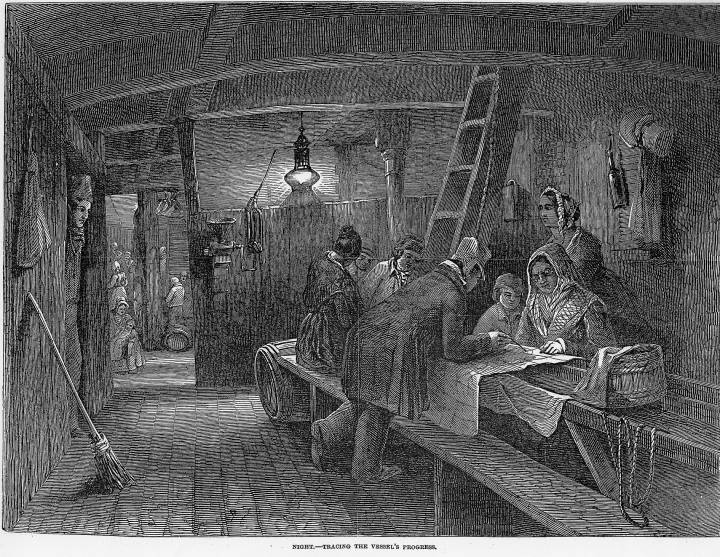

Night. — Tracing the Vessel's Progress. [Click on thumbnail for larger image.]

"The fineness of the night tempts all from below, when the deck becomes crowded, though all appear to enjoy themselves to the full: on the poop [deck] children are gambolling, whilst those in converse sweet, or on gossip most intent, keep up a continued promenade on the deck. Descending below, there a little group surrounds some learned friend, who has industriously worked the ship's course for the last day, and is now giving a detailed report to his companions, who all busily examine the amateur's well-thumbed chart, as if they knew a great deal about it. A little beyond, perhaps, the boatswain, from his cabin door, spins one of his long, marvellous yarns to his credulous open-mouthed neighbour on the opposite side. Further on, again, is the emigrants' quarters, the interior of which can be seen through an opening in the bulk-head. Good wives are now displaying their matronly qualities, but in most cases vainly endeavouring to calm the Baby-lonish confusion of tongues and screaming squall that, for at least one hour, prevails in the family compartment of the ship. To add to the quiet enjoyment of compelled, but resigned spectators, sundry night-capped heads of disturbed damsels, retired for the night, appear from their berths, but produce little effect by their complaining, whilst the unblanketed lower extremities of others, more calm and philosophic, may be also seen projecting from the narrow confines of their beds. But hark! Four bells is striking; 'Lights out!' is heard in various quarters; and in a few minutes, save the measured tread of the watch on deck, the rustling sails, and rippling waters on the vessel's way, not a sound is heard."

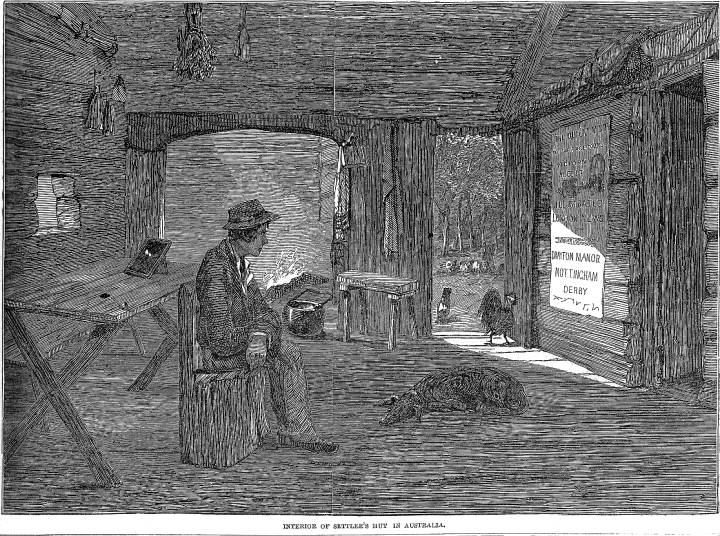

"We have engraved, from the same artistic source as the preceding Illustration — two views of the exterior and interior of a Hut in Australia, which we shall very shortly present to our readers.

Settler's Hut in Australia

Settler's Hut in Australia. [Click on thumbnail for larger image.]

The Sketch . . . represents an Australian dwelling, of a class commonly met with in the Bush. It is constructed of rudely split logs, placed upright in the ground, the interstices being in most cases filled up with mud or clay; but the peculiar circumstance connected with the Hut here drawn was this: —

On one of his sketching excursions, our Artist was anxious to cross some mountain tiers, in order to make a straight line to a spot he was anxious to visit, at some twelve miles distant. He was aware that there was no marked road; and that to attempt it without a guide would be to run a serious risk of losing himself in the intricacies of the wild forest with which the country is covered. However, he very soon had the gratification to reach a clearing, and to see, a few hundred yards before him, a column of bright blue smoke rising among the gum-trees, and indicating the hut of some settler.

Australian hospitality has become proverbial, and, says Mr. Prout, "perhaps few persons have experienced it more frequently than myself. My wanderings as a sketcher have often led me among scenes and in situations where I have been wholly dependent on such sources for food and shelter; and I have ever received it with a hearty good-will, and in such a manner as one might have inferred that I had been rather the dispenser than the recipient of such kindness. It was just so, at the time to which I have alluded. I made my wants known, and asa readily a young man who was the shepherd on the station offered to become my guide. Theis matter being settled, the iron pot was placed on the fire, and a plentiful repast of mutton chops and sassafras tea prepared us for our journey; but before we started, my fiend 'Joe' must have his pipe, and I must have my sketch. The interior of the little hut presented so quiet, so enticing a bit, that I must needs make a memorandum of it. Joe had smoked himself into a state of semi-dreaminess, and seated on a log of wood, displaying an attempt at the formation of a chair, was contemplating with a most thoughtful visage a large posting-bill — an advertisement of the ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS, announcing the Queen's visit to Drayton Manor, &c. Doubtless, dreams of greatness, and thoughts of home, were passing through the poor shepherd's mind: he appeared quite lost in thought, and in imagination was far, far away from the wilds of Australia; but his kangaroo dog, which had been lying at his feet, roused himself, disturbed his master's reveries, and at the same time afforded me an intimation that it would be well to commence our journey."

How the posting-bill, announcing the Visit of Queen Victoria to the Midland Counties of England, had found its way into the Settler's Hut, we are not informed; but there our Artist witnessed the affiche, treasured as a picture. [184]

Emigration of the Poor.

The following are the conditions which are inserted by the Poor-law Board in their orders sanctioning the emigration of poor persons: — 1. The party emigrating shall go to some British colony not lying within the tropics. — 2. The guardians may expend a sum not exceeding 3d. a mile in conveying each emigrant above seven years of age to the port of embarkation, and a sum not exceeding 1½d. a mile in conveying each child under seven years of age. — 3. The guardians may give to each emigrant, the place of whose destination shall not be eastward of the Cape of Good Hope, clothing to the value of �1, and may also expend a sum not exceeding 10s. for each emigrant in the purchase of bedding and utensils for the voyage. — 4. The guardians may give to each emigrant proceeding to the Cape of Good Hope clothing to the value of �2, and to each emigrant to places eastward of the Cape of Good Hope clothing to the value of �2 10s.; and in either case may expend a sum not exceeding �1 for each person above 14, and 10s. for every child above 1 and under 14 years of age; and in cases of free emigration, �2 for a single man above 18 years of age, in the purchase of bedding and utensils for the voyage. — 5. If the emigrant be not conveyed by or under the authority of her Majesty's Government to the place of destination, or provision be not otherwise made in a manner satisfactory to the said Commissioners for the maintenance of such emigranton arrival at such place, a contract, to be approved by the Commissioners, shall be entered into for securing a sum of money to be supplied to the emigrant on such arrival, according the following scale: to each person exceeding 14 years of age, �1; to each person not exceeding 14 years of age, 10s. — 6. If the emigrant be not conveyed by or under the authority of her Majesty's Government to the place of destination, and the cost, or any part thereof, of conveying the emigrant from the port of embarkation to such place, shall be defrayed from the fund above directed to be provided, a contract shall be entered into for conveying the emigrant to such place, to be approved by the said Commissioners. [184]

Related Material

References

Prout, Skinner. "Scenes on Board an Australian Emigrant Ship" and "Australian Hut" [six images plus accompanying excerpts from his journal]. The Illustrated London News. 20 January and 17 March 1849. Pp. 39-41 and 184.

Last modified 21 June 2024