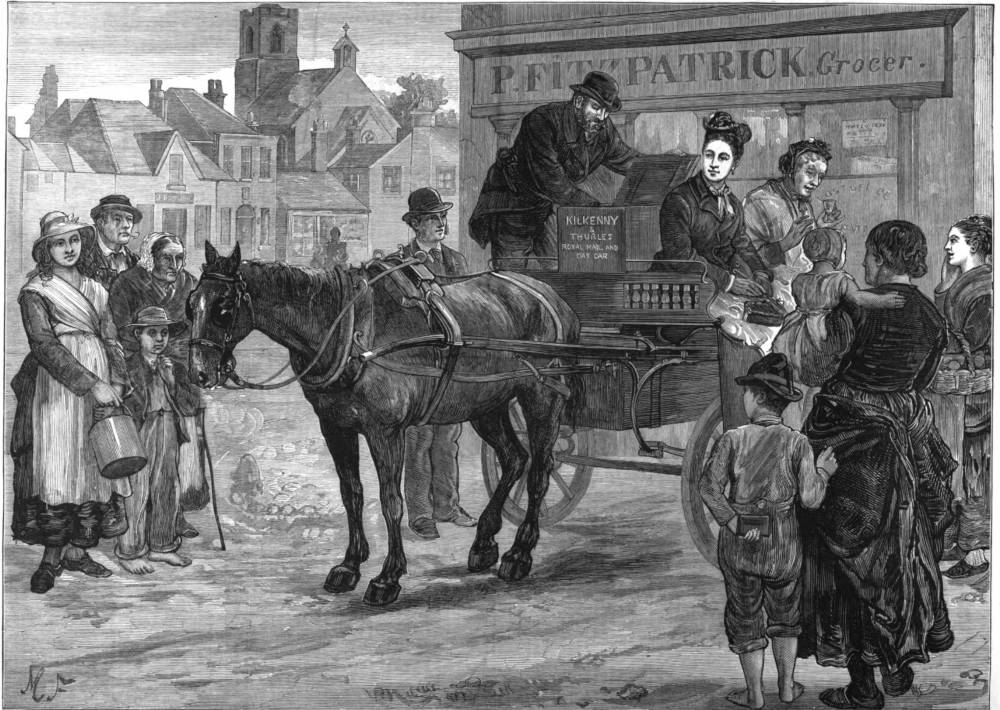

Irish Sketches: On Her Majesty’s Service. Illustrated London News 75 (29 November 1879): 500. Click on image to enlarge it.

The Illustrated London News Article on the Previous Page

The famous “jaunting-car” plays an important part in the economy of the Irish postal department. On hundreds of miles of road, the work of transmission is carried on chiefly by the aid of that singular vehicle, which is the delight of the natives, and the terror of all strangers who trust their bodies to it for the first time. In the capacious “well” —a kind of oblong box which lies between the “seats” on either side - a handy receptacle for post-bags is found; while the machine itself, whe behind a fast horse, can bowl at a highly respectable speed along a level road. The “mail-car differs somewhat in shape from the ordinary “side-car;” its “well” being rather broader and deeper, but it is most easily recognised at a glance by the reddish hue with which it is daubed all over. We do not remember having ever seen an Irish mail-car of this kind which seemed to have been painted within the present century. The colour has a gickly hue, as of a red that had grown pale with the gathering griefs of accumulated years, and it imparts to the vehicle an air of having seen better days, which is not lessened by the self - asserting inscription which invariably appears on the back in obstrusive yellow letters— “Royal Mail and Day Car. From -- to --- - miles.”

Our Artists’ sketch was taken at a village on the road between the city of Kilkenny and the town of Thurles, in county Tipperary. No railway communication had as yet been established between these two comparatively thriving towns, which are twenty-one Irish miles apart — a distance about equal to twenty-seven English miles. The mail-car traverses the road between Kilkenny and Thurles twice daily, carrying passengers as well as mails. Besides the driver, who is skilled in balancing himself securely on the little box in front, four people can be accommodated with seats on the vehicle, at the trifling rate of twopence each per mile. The driver, who acts as mail-guard, leaves a made-up bag at each rural post-office, and receives one in return, which he deposits in the “well of his vehicle. When the car, as happens in many places, arrives at the office during ordinary bedtime, the postmaster, roused from his couch, comes to a front window, with a long crook in his hand. The incoming mail - bag is hooked on to the crook, hauled in through the window, and retained, while the outgoing one is left with the driver by a similar process.

For his duties the rural postmaster usually receives no greater remuneration than £1 a year, out of which sum he must provide cord and sealing-wax; but, being almost invariably a shopkeeper, he undertakes those duties willingly enough for sake of the connection which the mail business may bring around him; and when, as not unfrequently is the case, he happens to be a publican, the revenue secured in this way should be a source of satisfaction both to himself and to the Excise department. Many a strange scene is witnessed at his threshold. Beggars, for instance, lie in wait for the arrival of the mail-car; not in the hope of intelligence by post, but in the expectation of open-handed passengers. Woe to the unlucky stranger who returns a harsh or uncivil answer to their oily supplications! The interrupted prayer for his weal may be suddenly lengthened into something remote from a bene diction, in this wise— “May the blessin ' o ' God folly you for ever an ' ever - an 'never overtake you;” or it may be supplemented by some ready sarcasm, such as — "Arrah, Judy, have you a copper at all to throw to that poor starved creature there on the car? He wants it worse than ourselves, God help him." Let the passenger be ever so stoical, those dirty but merry mendicants will make him feel well satisfied when the car is again in motion.

But the great “sensation scene is produced by the arrival of an American letther." It is well known that most of the Irish poor in the United States are mindful of their kindred in the "ould counthry," and freqriently transmit donations of £10 or £12 to the loved ones they have left behind, very many millions having been thus passed through the post office during the last two decades. Every private epistle, besides, is sure to contain a selection of news that will be absorbingly interesting to the ' people of the locality from which the writer emigrated. “An American letther," therefore, excites widespread commotion. The news of its arrival spreads like wildfire, and by the time its owner comes to claim it an eager crowd will have gathered nigh the office door. Someone is pressed into service for the decipher ment of the treasured scrawl - usually a child from the adjacent National School; and the people stand around in rapt attention, the silence being broken only by impulsive cries of joy or woe from a listener, to whom the reading may have announced the good fortune or disaster, perhaps the death, of an absent husband or lover, a brother or a son. [499]

[You may use the image above without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the Hathi Trust and the University of Michigan and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Last modified 27 June 2021