The following is the first of several extracts from the author's "A Comic Empire: The Global Expansion of Punch as a Model Publication, 1841-1936," originally published in the International Journal of Comic Art 15/2 (Fall 2013): 6-35. We are grateful to Professor Scully for allowing us to reprint some passages and images from it here. — Jacqueline Banerjee

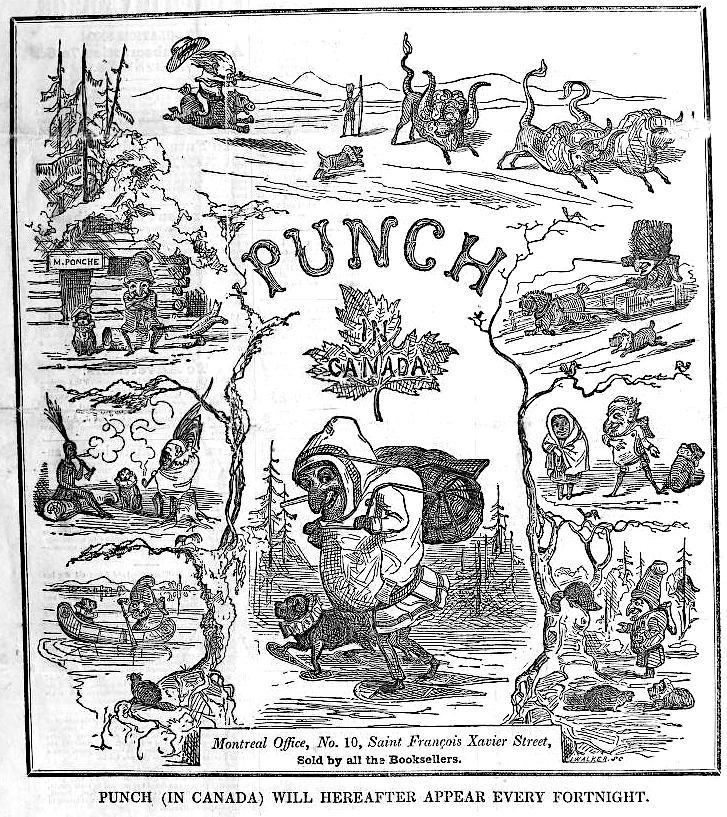

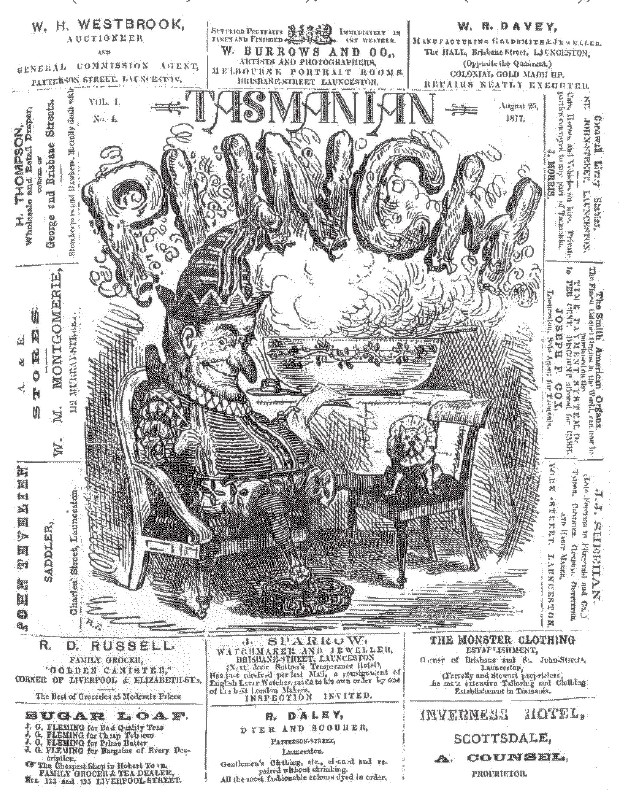

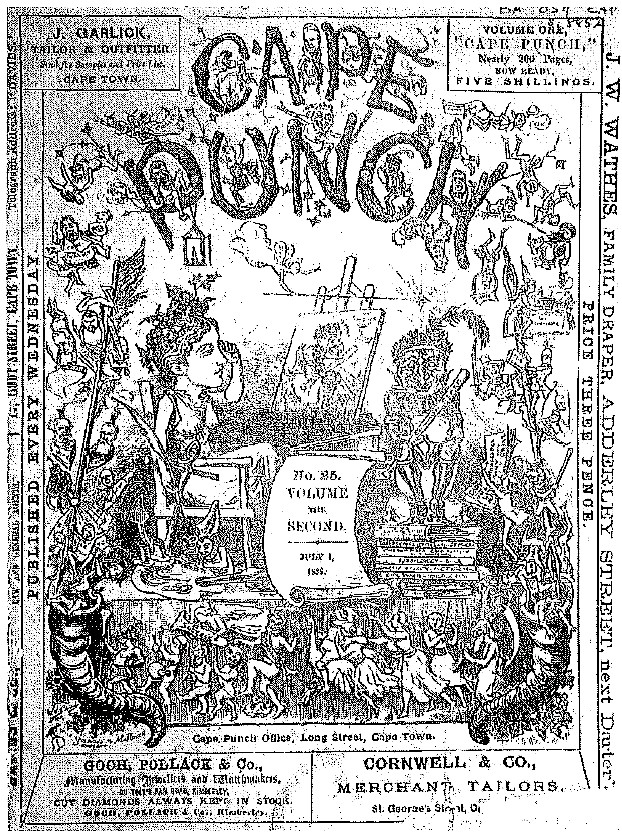

Cover illustrations, left to right: (a) J. B. Walker, Punch in Canada, 3 March 1849. Source: Scully 7. (b) Rudolf Jenny, Tasmanian Punch, 25 August 1877. Source: Scully 8. (c) W. H. Schroder, Cape Punch, 4 July 1888. Courtesy of Chris Holdridge. Source: Sully 9. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

[D]espite its unique status among comic papers, aside from a very few studies (Douglas, 1994; Bryant, 2008; Codell, 2006; Scully, 2012), the importance of Punch for that greatest of nineteenth-century enterprises — the British Empire — has been little appreciated. The otherwise unrivaled work of the late Richard D. Altick (1997) did not deal in depth with Punch as a key disseminator of imperial ideology, and did not touch upon the role Punch played as the center of its own "informal" empire. Not only was the London Charivari itself circulated widely throughout the British Empire — appearing on the news-stands from Montreal to Melbourne — but it spawned a whole host of colonial and other imitators. Some of these colonial Charivaris were short-lived — such as Punch in Canada (1849-1850) (above left), Tasmanian Punch (1866-1879) (above centre), and Cape Punch (1888) (above right) in South Africa — but many represented the first flowerings of a British style of satirical journalism that (together with its American counterpart) has arguably come to infuse all global political cartooning and caricature. The longer-lasting Melbourne Punch (1855-1925), Sydney Punch (1856-1857; 1864-1888), Hindu Punch (1871-1909), and Awadh [or Oudh] Punch (1877-1936), may have begun their lives as peripheral imitators ofthe metropolitan paper, but came to embody aspects of the emerging national consciousnesses of the Australian colonies and Indian provinces, and were foundations of the Australian and Indian traditions of comic art. [8-9]

Related Material

- 2. Regional and American imitators of Punch

- 3. Maintaining British identity abroad through Punch

- 4. Colonial Charivaris

- 5. An Indian Punch

Bibliography

Altick, Richard Daniel. Punch: The Lively Youth of a British Institution. Athens: Ohio University Press, 1997.

Bryant, Mark. Wars of Empire in Cartoons. London: Grub Street, 2008.

Codell, Julie. "Imperial Differences and Culture Clashes in Victorian Periodicals' Visuals: The Case of Punch." Victorian Periodicals Review, 39/4 (Winter 2006): 410-428.

Douglas, Roy. "Great Nations Still Enchained": The Cartoonists Vision of Empire, 1848-1914, London: Routledge, 1993.

Scully, Richard. "Constructing the Colossus: The Origins of Linley Sambourne's Greatest Punch Cartoon." International Journal of Comic Art, 14/2 (Fall 2012): 120-142.

Created 12 August 2019