Photographs by the author, 2023. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web project or cite it in a print one. Click on all the images to enlarge them, and, in the case of the De Drey Rooms, to find more information about them.]

A New Road

View of nos 1-9 St Leonard’s Place from Blake Street.

Several important new roads would be cut through the old city of York in the nineteenth century, most importantly: Parliament Street, 1834-6, with Barclay's Bank standing prominently on its corner; Duncombe Place, 1859-64; and Clifford Street, 1881, with the York Institute of Art, Science and Literature dominating its west side. But one of the first was St Leonard’s Place, named after the medieval hospital which had covered much of the area. The chief feature of the new road is seen above: in the photograph on the left are the columns of the 1828 portico of the Assembly Rooms by Pritchett & Watson, which had replaced the projecting apse of Burlington’s façade in a minor road improvement in 1828. On the right is the Red House, built for York’s MP in 1702-4, but later known as Dr Wake’s house: these were fixtures for which the new road had to allow.

Several possible routes were drafted by Peter Atkinson working with his elder son W. B. Atkinson in 1831- 33 for the corporation. Finally, this road was cut through a jumble of older properties, and through the medieval and Roman city wall, directly into Bootham, the road leading west and north from the city.

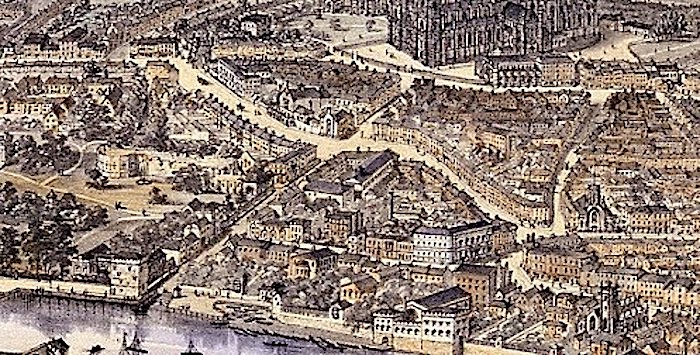

York in 1858 from Whittock’s panorama. Source: York Museums Trust (York Art Gallery).

Long-distance coaches leaving the city from inns in the Coney Street area needed a wider road and better angles to get through Bootham Bar. The route for coaches going west and north begins at the lower right, with Coney Street on which is St Martin’s church; then right into St Helen’s Square, made in 1745 by paving over the churchyard but still not at its present extent; then left into the curve of Blake Street, and then comes the rather overstated width of St Leonard’s Place; then turning left, at last, into a straight exit along Bootham.

Bootham Bar

Left: The inner face of the gate seen from High Petergate. Right: The outside of the gate in the city walls, seen from Bootham.

Although a length of the medieval wall, and the barbican which had projected into Bootham, were lost in making the new road, the Bar, or gate, itself was retained; it was given a mock medieval inner face by Peter Frederick Robinson, the designer of the Prison, in 1834 (Fawcett 2011, 33). It is detectable as a pastiche because there would be no need for arrow slits on the inner face of the gate. In the exterior view, the figures standing above the parapet were carved by G. W. Milburn, whose workshop was nearby: that was in 1894; they replaced earlier figures in a similar position (Pevsner & Neave, 194).

In the 1830s, there was rising sympathy in York for saving the old walls, a committee had raised a subscription for restoring them, and the archbishop was not therefore willing to approve the demolition of the whole of the Bar (Fawcett 2009, 20). So, the comeback of York’s walls was initiated, and even the arrival of the railway from 1839 could not demolish them.

The new road was needed not only because traffic in the city had become too much for the narrow streets, but also to provide income for the City Corporation: it owned much of the land and hoped to derive income from renting high quality properties on it. Building began in 1834, but it was some years before enough interest was shown to complete the chief feature proposed, a crescentic terrace of nine houses behind a unified façade. Investors were not grandees but connected with the council, or were architects or builders. Two of the nine plots at first were not used as houses, no. 1 was built to be let to the York Subscription Library, and the central plot, no. 5, was for a time the home of the Yorkshire Club. At present, the City of York Council is selling nos. 1-9, but owns the De Grey House and Rooms (see below). The Art Gallery is part of the York Museums Trust, and the Theatre Royal (also shown below) is owned by the York Citizens Theatre Trust.

The terrace of houses, nos. 1-9 St Leonard’s Place

Left: View of the central house, no. 5. Right: View of the north end of the terrace from near the Bar; the end house is no 9.

The unified façade was designed by John Harper, using stucco or “Roman cement” on brick, “treated as a dignified Greek Revival ensemble with paired pilasters emphasising the end pavilions” (Fawcett 2009, 25). However, the interiors were the work of various architects, as chosen by the individual purchasers. Although George Townsend Andrews’ design for the facade had been rejected, he designed the interiors of nos. 1-4 and no. 8; John Harper designed the interiors of nos. 5, 6 and 9; no. 7 may have been designed by James Pigott Pritchett.

Left: Balcony railing of the terrace. Right: Boot-scraper by the fornt door.

A particular feature of the development is the ironwork of the unifying balcony, and the various railings on the staircases inside; this was made by Gibson & Walker (Pevsner & Neave, 231), though the ironwork is assigned to Walker’s in Walmgate by Fawcett 2009, 25. The two were connected: John Walker had been Gibson’s apprentice, but was a partner by 1829, and bought out Gibson’s in 1837. These railings therefore are probably one of the earliest examples of what was going to be seen as Walker’s excellence as a supplier of cast iron railings nationally. Boot-scrapers survive, at nos. 1, 2 and 6. One is formed of two dolphins and an anthemion, the others of anthemions alone. The scraper at no. 1, shown above, is at a blocked doorway on the Museum Street side of the building, which formerly led only into the News Room of the Library.

Extensive illustrations of all the interiors at the time when nos. 1-9 were still being used as Council offices are given in Fawcett 2009, including drawings for ironwork by Harper which are in the City Archives. In about 2010, after some 50 years of use by the Council (Fawcett 2009, 25), the offices moved to the former railway station terminus on Toft Green designed by G. T. Andrews. Use by the Council had been kind to the interiors; the nine houses have been restored and are being sold.

Mr Blanshard’s House, now known as De Grey House

Left: General view from the other side of the street. Right: Side view from the front of the Theatre Royal

G. T. Andrews’ partnership with P. F. Robinson ended in July 1837, about a month after the accession of Queen Victoria. Andrews had been building up a practice in the city while superintending the construction of the Prison designed by Robinson; he had an office in 31 Castlegate which his succeeding practice retained for decades. Up to 1837, anything Andrews had designed would have appeared as by the partnership. Hence, this house opposite the terrace, “was built for William Blanshard to designs dated 1835 by P. F. Robinson and G. T. Andrews. Built of brick rendered in ‘Roman Cement’ to front and side, the house is of three storeys with basement and attics in the slated mansard roof” ("De Gray Rooms"). This roof is not so noticeable as the one on the terrace, but added an extra storey to the accommodation.

On this side of the road too, take-up was slow, and the three houses projected here never materialised. Only Mr Blanshard’s house was built.

De Grey Rooms

Left: The Bar and the De Grey Rooms with stub of medieval walls and new stairs between them. Right: Seen from the north side, the beautiful white façade is a screen for a brick and wood structure fitted into an awkward space.

Eventually the space between the house and the stump of the medieval wall was taken up when the "De Grey Rooms were built by subscription in 1841-42 to the design of G. T. Andrews. The impetus for the erection of the building was given by the Earl de Grey and officers of the Yorkshire Hussars who required suitable accommodation for their annual mess. It was intended to be used for concerts, balls, public entertainments and meetings” (York Conservation Trust). The colonel, Thomas Philip, Earl de Grey (1781-1859), was also known as a very capable amateur architect and was first president of the (Royal) Institute of British Architects (Fawcett 2009, 24-5, 42-3). Fronting St Leonard's Place, it has an entry at the north end which provided a carriage drive round to Mr Blanshard’s house.

Later developments

Theatre Royal, 1877 façade.

Later developments completed what is now seen along this street. The present facade of the Theatre Royal replaces one designed by John Harper in 1834-5. It was designed by the City Engineer, George Styan in 1877-9 (Pevsner & Neave, 198). This façade uses medieval architectural features of various periods; the heads in roundels are probably intended as characters in plays by Shakespeare.

Left: The oriel window, with four of the heads in roundels on either side, above and below. Right: The eyes of this character at street level have been coloured in.

When this theatre opened in 1744, and was enlarged in 1764, it had an insignificant entrance on Little Blake Street. John Harper’s front can be glimpsed in the Whittock panorama, but looks no loss: three bays of the eight-bay entrance arcade survive at 79 Fulford Road, it might be described as Tudor Gothic in style, again a reference to the national playwright (Murray 10-11; York Mix website).

The open area between the façade of the theatre and the De Grey House represents a garden planned in the 1840s (Fawcett 2009, 23, 24). A watercolour by Charles Dillon (dated to 1830 but must be at least 1835), shows a view taken from the north end of the terrace across this garden towards the Minster; it shows Blanshard’s house on the left, and part of Harper’s façade to the theatre on the right. There is ample space for the tiny coaches to pass each other, just as on the panorama – York must have been very proud of the new road!

The Art Gallery of 1879, designed by Edward Taylor, stands on Exhibition Square which was laid out at the same time. Besides those already mentioned, several additional roads were cut: Foss Islands Road, 1853, is outside the city, but there was lobbying to retain the walls alongside it; and on the south bank of the Ouse were Queen Street bridge, in about 1840, Priory Street in the 1850s, and Station Road in the 1870s. York was becoming the city we know today.

Bibliography

"De Grey Rooms." York Conservation Trust (a useful site for other buildings too).

Directory of York. (Published by) George Stevens, 1885. Leicester University Digital Collections: 97-98.

Fawcett, Bill. George Townsend Andrews of York: “The Railway Architect." . York: YAYAS and North Eastern Railway Association, 2011.

_____. "St Leonard’s Place: Its Development and Buildings." York Historian 26 (2009): 18-47.

An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 5, Central. Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1981.

Murray, Hugh. A Directory of York Pubs, 1455-2003. York: Bullivant, 1988.

Pevsner, Nikolaus, and David Neave. Yorkshire: York and the East Riding. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002.

"Saved – the 180-year-old York Theatre Royal arches threatened with demolition." York Mix. 4 January 2023.

Created 4 January 2023