[Click on photographs to enlarge them.]

Commentary by John Lucas Tupper (1872)

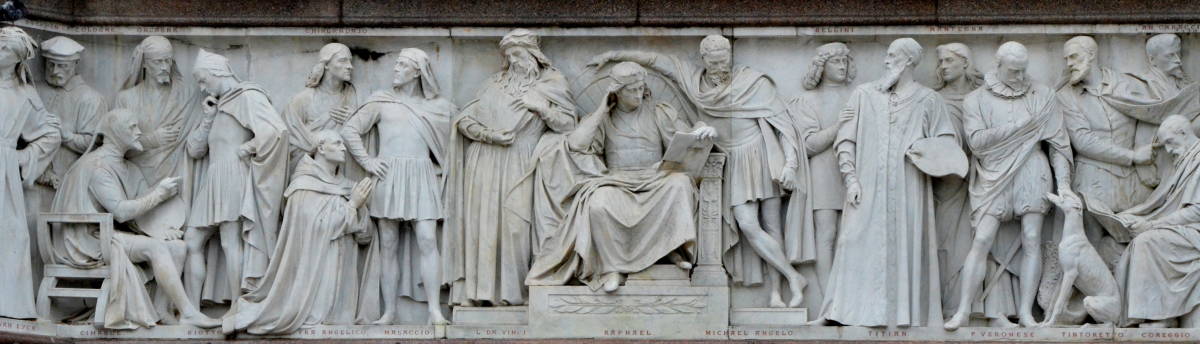

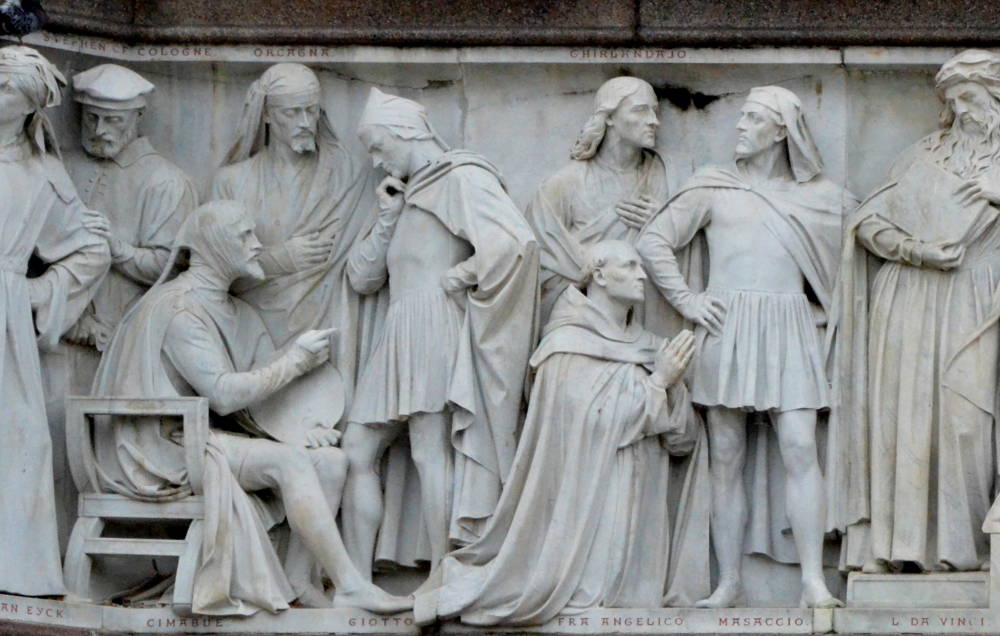

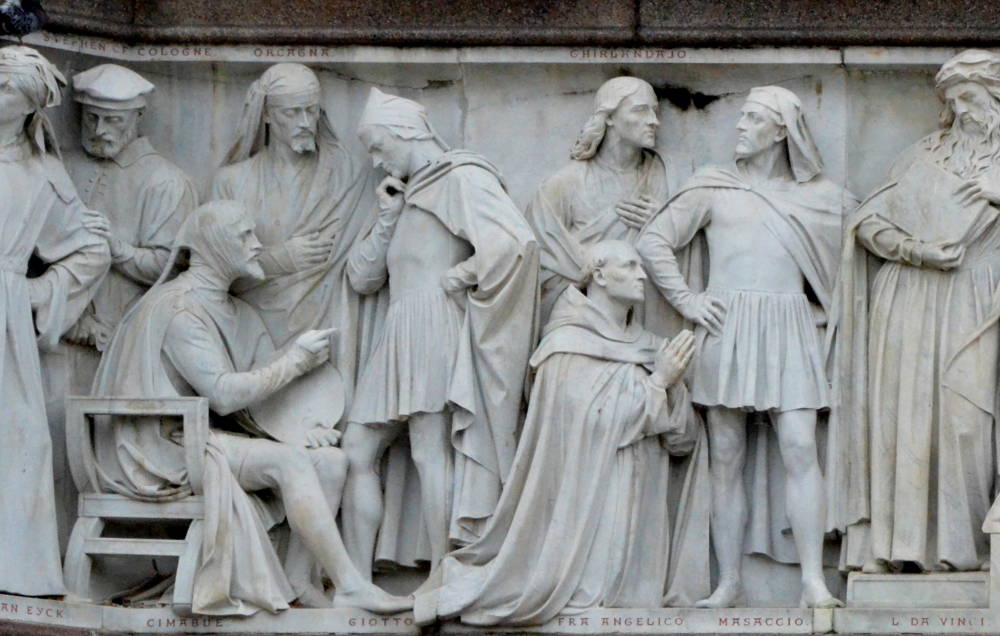

The painters occupy the east front. Raffaelle, seated in the centre upon a circular-backed throne, is looking at a volume of designs, half approving, half fastidiously. His fingers let in the cool air amongst his curls. Michael Angelo leans slantwise on his left, almost encircling the back of the throne with his right arm, his legs crossed, and his head drooping over in thought. Da Vinci, who stands on Raffaelle's right hand, leaning on the throne and almost turning his back to it, is very discerningly conceived, especially when certain critics are appraising him as a merely scholastic painter, and would no doubt have him holding a pair of compasses. But he holds his book of great thoughts near his heart. Propped on one leg, the hip thrown out, he leans further and further back, while his head drops further and further forward. And he must have stood thus who was not prone to give up restlessly any attitude of thought or feeling, but to carry it further and still further to some sublime consummation.

On the right of him stands Masaccio, a most vigorous conception, with hands at his hips and head turned over his shoulder. The saintly Angelico is on his knees beside him, while in the space above appears the passionate face of Ghirlandajo. Giotto stands near, conversing with Cimabue seated, Orcagna behind and between them.

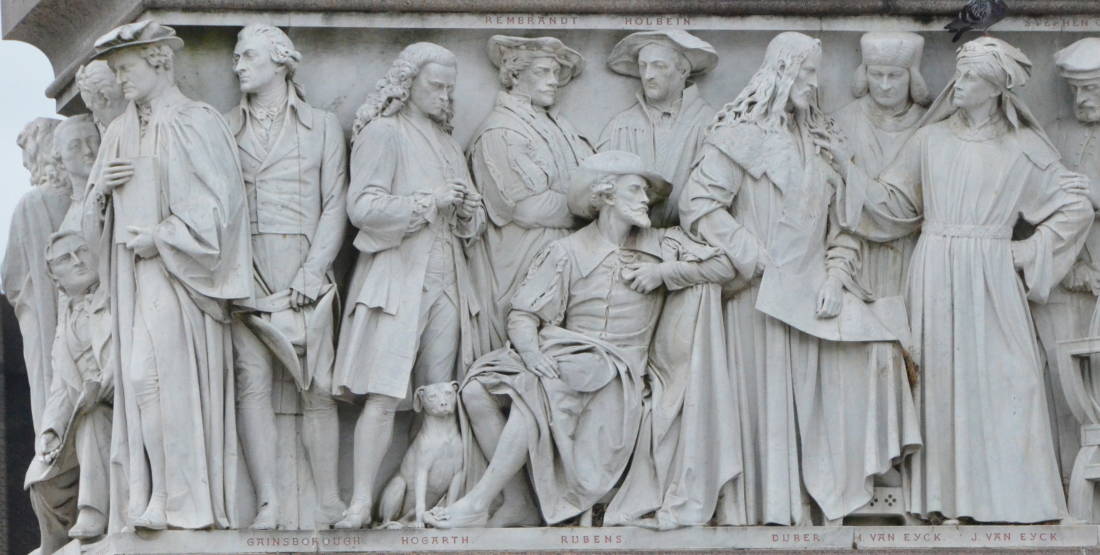

Then comes an upright figure, John Van Eyck, who, with left hand on hip, lays his right on Albrecht Durer's left breast, as taking counsel on some deep point of art-science. Durer looks grand and gracious with his inclined, attentive head. Van Eyck's brother interposes from behind, and Stephen of Cologne completes the group. The fur-trimmed mantle of Durer masses richly with his long pendent locks, contrasts effectively with the simple surfaces of Van Eyck's drapery, and melodises with the rich slashed costume of Rubens, who sits next, a picturesque figure full of spirit. In the space above this sitting figure of Rubens, and a little recessed, appear Rembrandt and Holbein, the rich dresses of whom complete the mass of decorative surface demanded for the contrast just mentioned. Next to Rubens stands the observant Hogarth, looking innocently abstracted, but sleetching some face upon his nail; his dog is between his legs.

By his side is Gainsborough; and Reynolds, a graceful, thoughtful figure, occupies the salient angle of this wing, the face of which presents Turner seated and looking up at Wilkie.

The princely Titian rears his mantled figure on the left of Angelo, with Bellini between them, his hand on Titian's arm. Veronese is next to Titian, his right hand half buried in his rich mantle and his left on a greyhound's head. Mantegna is seen between him and Titian. Coreggio, voluminously draped, and massed, by means of the dog and a rich-plumed hat upon the ground, with the figure of Veronese, is sitting examining designs; while between these figures, a little recessed, and offering a highly decorative surface, we have Tintoretto flinging himself round, his cloak floating back with the motion, and carrying out and clearing up most important lines in the composition, the consummate harmony of which is beyond praise. Next to Coreggio, Velasquez stands erect and stately. A little behind, on his left, is Murillo; and on his right, and above Coreggio, are the two Caracci.

Photographs, text, and formatting by George P. Landow. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Tupper, J. L. “Henry Hugh Armstead,” English Artists of the Present Day. Essays” by J. Beavington Atkinson, Sidney Colvin, F. G. Stephens, Tom Taylor, and John L. Tupper. London: Seeley, Jackson, and Halliday, 1872, 61-66.

Pevsner, Nikolaus. Berkshire. London: Penguin, 1988.

Content last modified 12 November 2011

Reformatted 16 March 2015