Chantrey: a name which has conferred lasting celebrity on the village of Norton" — John Holland, p. 1.

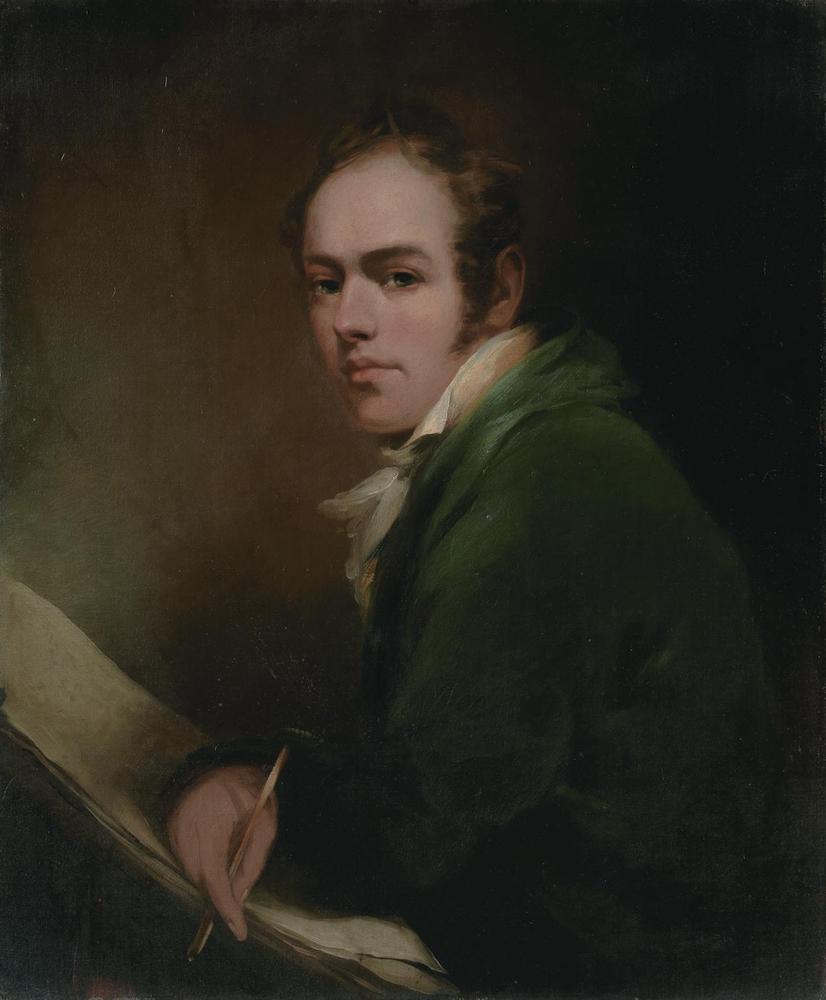

Sir Francis Leggatt Chantrey by Thomas Phillips, 1818, © National Portrait Gallery, London, by kind permission.

Francis Leggat Chantrey was very successful and greatly admired during his lifetime, and still occupies an important place in the art world. As one of his early biographers, John Holland, wrote in connection with his subject's charitable bequests (having made it plain that the same could be said of his sculptural oeuvre) "Though dead ... he yet speaketh" (345).

Chantrey's beginnings were humble enough. His cottage birthplace, now marked with a plaque, was in the hamlet of Jordanthorpe, within the parish of Norton, just five miles outside Sheffield. Stories of his early life, as recorded later by Harold Armitage in his book on "Chantrey Land," were well known there. Armitage tells how he learnt to draw on the kitchen flagstones at home; how his first job was driving a donkey loaded with milk churns down to Sheffield; and how he was apprenticed there to a carver and drew portraits of local businessmen. It was in "Chantrey Land" that his talent first manifested itself; and it was in "Chantrey Land" that he would eventually be laid to rest.

Chantrey's birthplace. Holland, title page.

From Norton, the gifted youth made his way to London to study at the Royal Academy. He soon turned to sculpture, exhibiting there in 1808. The first decisive step in his career were the busts commissioned in 1807 by the Naval Asylum Greenwich (now the site of the Greenwich Maritime Museum) of the Admirals Duncan, Howe, Vincent and Nelson, but real fame came in 1812 with his statue of George III for the Council Chamber at Guildhall; according to the biography written by his friend George Jones, this was "a good type of the whole-length statues he subsequently produced with such eminent skill in grandeur of design and boldness of execution" (15). Chantrey also carved a bust for the King who was so pleased with it that he insisted on paying 300 guineas, double the sum the sculptor was charging at the time.

In 1819 Chantrey travelled further afield, to Rome, where he enjoyed studying the paintings of Raphael, an artist he greatly admired, and also met Canova, the most successful sculptor of the age. However Chantrey was critical of the amount of finish and ornamentation in Canova's work, preferring the work of Thorvaldsen which, like his own style, was simple and more rugged. Jones wrote that Chantrey's work "depended entirely on form and effect. He took the greatest care that his shadows should tell boldly, and in masses. He was cautious in introducing them, and ... never introduced a fold that could be disposed with, ... and avoided abrupt foldings" (84-85).

Chantrey had married in 1809 and moved to Pimlico in London where he built a house, with separate workshop nearby. He lived here for the rest of his life.

The eminent sculptor's character is well summed up by E. Beresford Chancellor: "Fond of a joke, amiable and pleasing in his manners, he was received with pleasure in the mansions of the great and the dwellings of the poor. No wonder that his death, which proved a national loss, should have been mourned by legions of friends whose sincere regard he had won and preserved" (Chancellor 296).

Chantrey died in 1841 and, apart from charitable bequests to the poor, left his considerable fortune (estimated then at £150,000) to the Royal Academy of Arts, according to the instructions in his will to purchase for the nation "works of the highest merit" executed entirely in Britain (though not necessarily by British artists), and to buy them not only at a fair but "liberal" price, without being swayed by personal sympathy or preferences of any kind (Chantrey's own italics, pp. 18-19). The scheme, known as the Chantrey Bequest, has been working ever since, and is still active today. Among the many famous works acquired in this way and illustrated in Chantrey and His Bequest are Frederic Leighton's An Athlete Struggling with a Python, acquired in 1877 for £2000 (p.41); John Singer Sargent's Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, acquired for £700 in 1888 (p.70), and Henry Tuke's All Hands to the Pumps, acquired for £420 in 1889 (p.78). At first the growing collection was housed in the South Kensington Museum (as it was then), but in 1897 they were transferred to the Tate (see Chantrey and His Bequest, p. 24). The Bequest, still administered by the Royal Academy, has been been both a boon to artists and a tremendous gift to the public at large.

The Burial of Sir Francis Chantrey in Norton Churchyard, Sheffield, by Henry Perlee Parker (1795–1873). 1841. Oil on canvas. H 37.1 x W 57.8 cm. Collection and photo credit: Sheffield Museums. Accession no. K1905.10. (Art UK)

"Chantrey often said that, if he had his choice, he should prefer a grave in the quiet church-yard at Norton, to one in St Paul's Cathedral or Westminster Abbey" (Holland 323). His wish was granted. Many people came out to see Chantrey's cortège pass by on its route from London, where most of his own work had been done, to be buried in the Norton churchyard; and, despite inclement weather, large crowds came for the funeral. His tomb seems typical of the man, a huge slab of polished granite lying on the ground outside the church door (a spot chosen by himself, according to the early sources, including Chancellor, p. 295) with just his name and dates deeply incised. It was surrounded with a low railing. In 1854 an obelisk 22 feet high, designed by his friend Philip Hardwick, was erected outside the churchyard.

Bibliography

Armitage, Harold. Chantrey Land: Being an Account of the North Derbyshire Village of Norton. London: Sampson Low, Marston & Co., 1910.

Chancellor, E. Beresford. The Lives of the British sculptors, and those who have worked in England from the earliest days to Sir Francis Chantrey. London: Chapman & Hall, 1911. Internet Archive, from a copy in Robarts Library, University of Toronto. Web. 21 January 2024.

Chantrey and His Bequest: A Complete Illustrated Record of the Purchases of the Trustees.... London: Caseell, 1904. Internet Archive, from a copy in the Gety Research Institute. Web. 21 January 2024.

Holland, John. Memorials of Sir Francis Chantrey, RA, Sculptor in Hallamshire and Elsewhere. London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longman, 1857. Google Books. Free Ebook.

Jones, George. Sir Francis Chantrey, R.A.: Recollections of his life, practice and opinions. Internet Archive, from a copy in the Getty Research Institute. Web. 21 January 2024.

"Sir Francis Chantrey." St James Norton: The Great Church." Web. 21 January 2024. https://www.stjamesnorton.org/sirfrancischantrey.

Created 21 August 2017