iles's Hero represents a major accomplishment by a representative member of an important group of young women sculptors, many of whom had trained at South Kensington. According to Susan Beattie, the authority on the New Sculpture who was the first scholar to direct attention to these young women, Giles was one of a group that included Florence Steele, Ruby Levick, Esther Moore, and Gwendolyn Williams, all of whom studied modelling in the early 1890s under Edward Lanteri at the National Art Training School (now the Royal College of Art) at South Kensington, winning prizes in National Art Competitions during the early 1890s (Beattie, 195).

iles's Hero represents a major accomplishment by a representative member of an important group of young women sculptors, many of whom had trained at South Kensington. According to Susan Beattie, the authority on the New Sculpture who was the first scholar to direct attention to these young women, Giles was one of a group that included Florence Steele, Ruby Levick, Esther Moore, and Gwendolyn Williams, all of whom studied modelling in the early 1890s under Edward Lanteri at the National Art Training School (now the Royal College of Art) at South Kensington, winning prizes in National Art Competitions during the early 1890s (Beattie, 195).

The official catalogues of the annual Royal Academy exhibition show that in the mid-90s women suddenly exhibit in large numbers. Although almost no women exhibited works of sculpture in the late 1880s, the following women appear as exibitors in the 1896 catalogue: Esther M. Moore, Kathleen Shaw, Florence Newman, Ada F. Gell, Florence H. Steele, M. Lilian Simpson, Lilian V. Hamilton, Ella Casella, Nelia Casella, Lydia Gay, Fraces A. Dudley Rolls, L. Gwendolyn Williams, Andrea C. Lucchesi, Rosamond Praeger, Countess Fedora Gleichen, Edith Bateson, Honora M. Rigby, Frances I. Swan, Hon. Lady Rivers Wilson, Edith A. Bell, Emily A. Fawcett, Alice M. Chaplin, Ruby Levick, and Margert M. Giles. Twenty-four out of approximately eighty exhibitors were women; one cannot determine the gender of a half dozen or so of the other exhibitors.

According to Susan Beattie,

the dramatic rise of women sculptors to prominence in the 1890s was directly related to the changing image of the art. The cult, not only of the statuette, but of modelling as the sculptors most direct means of self-expression, and the consequent revolution in the bronze founding industry, had deeply undermined the principal argument against women's involvement in sculpture, their inability to cope with the sheer physical effort it required. [Beattie, 195]

The new emphasis upon modelling clay, as opposed to stone carving, led directly to the entrance into the field of large numbers of young women. One must also point out, however, that once these women began to exhibit, many, like Giles, produced works with hammer and chisel as well as with the tools of the modeler. But the new fashion for bronze first made a radical new opportunity for women in the arts. Furthermore, these young women not only began to work with supposedly masculine tools and media they also worked with their subjects as well. For example, R. Ruby Levick exhibited a group of boys wrestling and Rugby Football (1901), and Lilian Wade produced bas reliefs of military scenes (see Wood).

In Hero, Giles realizes much of the potential created by this new opportunity, but she does so by reinterpreting a subject and a sculptural theme usually considered particularly appropriate for women. In particular, it departs from conventional conceptions of the female nude, and it thereby demands new aesthetic standards and makes new, or at least unconventional, claims about women. In addition, Hero challenges not only conventional conceptions of the female figure suitable for art but also conventional interpretations of a commonplace theme or structure.

A major part of Mspan class="sculpture">Hero's importance to the history of British sculpture derives from its relation of scale to basic conception. As Beattie points out, "despite the interest taken in the statuette since the mid-1880s surprisingly little attention had been given to the question of the relationship between scale and design" (Beattie, 196). In fact, almost all British statuettes exhibited before the turn of century were simply reduced versions of larger works that did not take into account the implications for design of changed size and scale. In contrast, the "complex. spiralling composition" of Hero derives from the "actual size of the bronze," and the sculptor has "presupposed the ability and inclination of its owner to vary its position, and so gradually discover, from a fixed viewpoint, its whole implication as a three-dimensional work of art" (Beattie, 195-196).

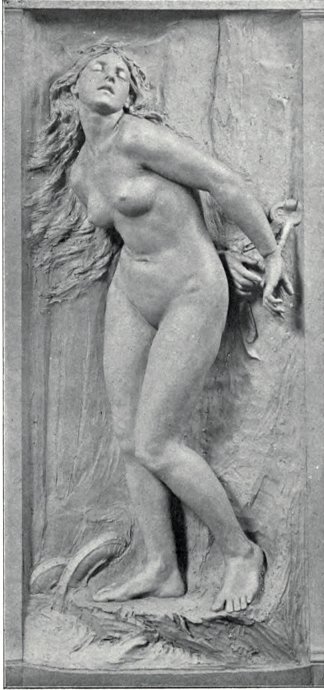

Left: S. Nicholon Babb's The Victim , 1905.

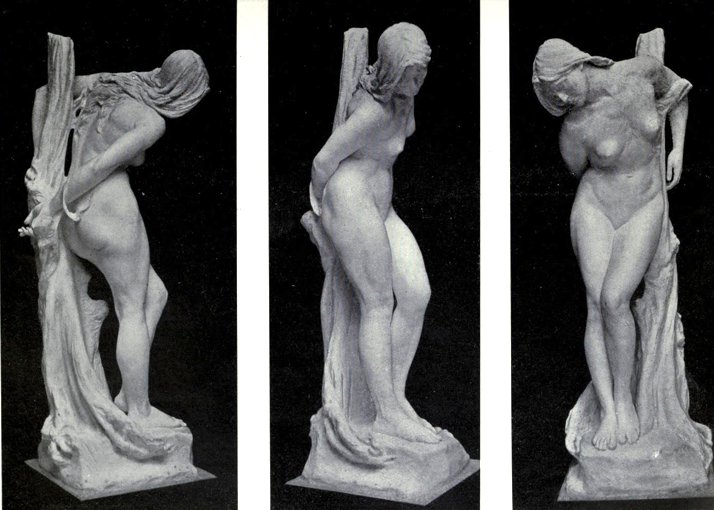

Right: Benjamin Clemens, Immolate (three views), 1912.

Although Hero's brilliant reinterpretation of the statuette owes little to the fact it was sculpted by a woman, its reinterpretations of the female nude do. Comparing it to several contemporary works makes clear Giles's originality in creating an active, powerful nude. Captive (1908), a work by a Miss J. Delahunt, is a clothed female figure seated in a pose roughly analogous to that of Giles's statuette. Here, the image is of passivity and acceptance, if not despair. S. Nicholon Babb's The Victim (1905), a bas relief of an Andromeda-like nude chained to a cliff, represents another standard image, popular throughout the nineteenth century, of the bound woman helplessly awaiting her fate, and Benjamin Clemens's Immolate (1912), which dates from the same year as Giles's scriptural frieze, presents an even more extreme image of a bound nude whose nakedness is emphasized by the garment that has been peeled away from her and hangs only from her arms. The work by Delahunt represents a passively accepting woman, those by Babb and Clemens an intensification or exaggeration of that theme in the situation of the bound nude. Giles, in contrast, creates a representation of woman -- even a suffering or anxious woman — as a far more free and active being.Part of the relative uniqueness of Hero arises in its emphasis upon a physically powerful female nude. A comparison with these others works reveals that at the time Giles sculpted her prize-winning representation of Hero, her conception of the female nude must have seemed particularly androgynous. Unlike Burne-Jones, who often created androgynous female figures by using male proportions for female nudes so that the resulting figure appears that of a young boy with breasts, Giles produces a nude with ample breasts and hips. The androgyny of her nude derives from its extraordinarily heavy musculature, which makes the figure appear a descendant of Michelangelo's gnudi. Looking at the figure's left arm, which supports her as she turns anxiously to search the darkness for Leander, one perceives tensed bicep, tricep, and forearm. Similarly,Hero's right upper thigh, which she has drawn slightly behind her, has a deep hollow, which similarly indicates mental and physical tension. Even today, when the standard of female beauty has moved toward greater muscularity or at least toward muscle tone than ever before, Hero's back strikes one as unusually well muscled — almost as if Giles had chosen for her model a twentieth-century woman shotputter or bodybuilder.

What else has Giles done to the conventional female nude in this representation of the anxious Hero? In the first place, she has rejected basic understandings of feminine beauty commonplace in her time. Within the context of contemporary figural types for the female nude that emphasize classicizing elements like calm, dignity, balance, stasis, Hero appears passionate and powerful. Within the context of female nudes that emphasize a lack of muscularity and definition as a prerequisite of female beauty, she appears an equally contradictory embodiment of power. Giles's work, which aggressively rejects the image of woman as an embodiment of roundness and softness, thereby reinterprets a convention or code created by men. In creating Hero , Giles has seized control of the cultural discourse in question — here that of the artistic representation of women — and given that code, convention, or form her own meaning.

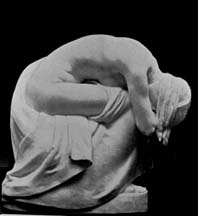

Bertram Mackennal, Grief. marble. 1898.

One can gain a notion of what else Giles has rejected by examining other representations of the female nude and of female grief. The passivity and lack of emotion that characterizes many nineteenth-century female nudes appears in contemporary sculptural representations of grief as well. Bertram Mackennal's marble statuette Grief (1898) presents the extreme emotion it embodies by means of a closed-in form, all emotion being expressed by the figure's curved back and hidden face. Like so many other images of women undergoing extreme emotion, this one presents the feminine in an image of powerful feeling pent within, rather than radiating outwards. Alfred Buxton's Isabella (1912), an idealized version of the Boccaccian literary theme made popular by Keats, Millais, and Hunt, presents the mad, mourning heroine crouched over the head of her murdered lover. Again, woman's grief, woman's emotion, is presented as calm enclosed within female form, and agony transforms to culturally aceptable melancholy.Considered in terms of its overall intellectual structure, Hero is one of many popular nineteenth-century artistic subjects that partake of what one can term the woman-waiting-by-the-water, another form of which appears in the many depictions of Ophelia playing with flowers before she enters the fatal stream. Those by Richard Redgrave and Arthur Hughes are among the best known. A second version of this theme appears in the naturalistic representations in late Victorian painting of women, usually the wives of fishermen, waiting for their overdue husbands to return. Local details that situate the image within a particular, identifiable, locatable time and place characterize Frank Bramley's Hopeless Dawn, Frank Holl's No Tidings from the Sea, and Walter Langley's But Men Must Work and Women Must Weep.

Edward G. Bramwell' Hero Mourning over the Body of Leander. 1908.

A more typical rendition of the Hero subject itself appears in Edward G. Bramwell's Hero Mourning over the Body of Leanderin which the grieving woman, face hidden, folds herself over the body of her dead lover. Comparing this fairly effective work to that by Giles, one is struck by the way Bramwell's Hero literary effaces herself, simultaneously creating an effective image of grief and a cultural acceptable political statement about the proper relation of woman to man. Face hidden, she folds into and around the man's body and dead maleness dominates the work even more than properly feminine grief.In contrast to such works, Giles has defined the female partner in an erotic relationship as more active than traditionally conceived. Her statuette's musculature, which conveys to the viewer a sense of unusual power, contrasts markedly with the usual conception both of the nude and of the Hero theme. Both are generally represented by nineteenth-century artists in paint, stone, and bronze as passive beings invaded by emotions. The conventional nude's rounded arms and flanks, which graph the ideal of male desire, embody a passive form, one smooth and graceful but completely without force. In fact, this lack of power provides a major source of this figure-type's complementary erotic and artistic appeal, an appeal that had been explicitly codified as an aesthetic doctrine since Edmund Burke opposed the powerful masculine sublime to an essentially passive beauty.

Burke, whose Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful (1757) made "terror . . . the ruling principle of the sublime" (58), explained the opposition between it and beauty by a physiological theory. He made the opposition of pleasure and pain the source of the two aesthetic categories, deriving beauty from pleasure and sublimity from pain. According to Burke, the pleasure of beauty has a relaxing effect on the fibers of the body, whereas sublimity, in contrast, relaxes these fibers. Burke further underlines the opposition of the two aesthetic categories by making beauty essentially feminine and sublimity masculine, and in so doing he quite explicitly reduces the importance and value of the beautiful. He also reduces the importance and value of the feminine, since by his reasoning the feminine and the female cannot be great. In Hero Giles rejects this reductive opposition of male and female by creating a sublime female nude and demonstrats, certainly to the satisfaction of Lord Leighton, who awarded her work first prize, that the female figure can be a source of power as well as of languid beauty.

This intonation of the traditional female nude is not the only one that Giles makes in reinterpreting the traditional figure of Hero. Hero reinterprets the traditional subject of the deserted or abandoned woman by making the body type more intense and heroic and by creating an unsettling emotionality so suffused with angst that it borders on the grotesque. In so doing, Giles offers a redefinitions of the feminine and the femininely appropriate. Her muscular, straining nude grounds the emotional intensity that is the second part of her reinterpretation — the reassertion of a woman's right to a powerful emotional life. Unlike almost all other representations of this theme that I have encountered, Giles's presents a woman actively searching the world around her. In so doing, she transforms what had been a purely contemplative, or even passive and suffering, form closed in upon itself — a quiet female center cut off from the outside world — into a consciousness that actively pentrates surrounding space, radiating a sense of force and activity.

When perceived within the context of contemporary and traditional conceptions of sculpture, Giles's Hero embodies changes in the basic conception of the art, particularly those conceptions related to medium and scale. As we have observed, it also embodies those attitudes related to gender, in this case the gender of the artist, and in fact the basic conception of Hero depends upon the entrance into the field for the first time of women in large numbers. In particular, when perceived within the context of contemporary and traditional conceptions of the female nude, this work makes strong statements about the nature of women, art, and beauty. Giles also makes clear statements about the role of the woman artist and about the nature of her contributions to art and to the understanding (or redefinition) of woman. As Hero further reminds us, work in an ideal or mythic mode, which by definition might seem removed from contemporary concerns, in fact permits the artist to emphasize precisely those issues that most concern her. In this case, a woman artist's sculptural representation of a nude woman from an ancient narrative permits her to reject contemporary cultural constructions of female nature and replace them with those that emphasize strength, activity, and power.

- Margaret M. Giles's Hero and the Sublime Female Nude: Introduction

- Margaret Giles's life and career

- Bibliography

Last modified 4 January 2005