Westmacott’s pedimental sculpture for British Museum, London, which dates from 1851, was officially unveiled in 1852 (see Bryant 316). The sculptural composition over the portico of the south entrance to the British Museum is in Portland stone, with the sculptures in the round (not in relief). It shows, in narrative progression, an allegory of man's development through the ages, acquiring knowledge and skills in the arts and sciences, as well as natural history. It carefully incorporates items actually to be found inside the museum, in this way preparing the visitor to see the museum "as the simultaneous representation and fulfilment of that progression" (Gidal 12).

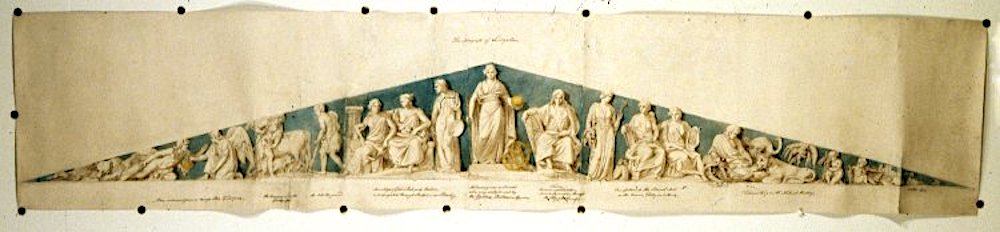

Westmacott's presentation drawing of the group of sculptures, probably dating to 1851, when the work was installed (see Bryant, 327, n.20). © The Trustees of the British Museum. Source: "Drawing."

Westmacott's design on paper, which includes animals, both domestic and wild, is a "brush drawing in brown wash, with pen and brown ink and watercolour, over black chalk" ("Drawing"). As completed, the project was his "largest single design" (Bryant 315) as well as his last, and of considerable interest. This is how he put it himself, in a letter of 23 May 1851 to Henry Ellis (1777-1869), then the museum's principal librarian:

Commencing at the Eastern end, or angle of the Pediment, man is represented as emerging from a rude savage state, through the influence of Religion. He is next personified as a Hunter, and a Tiller of the Earth, and labouring for his subsistence. Patriarchal simplicity then becomes invaded and the worship of the true God defiled. Paganism prevails and becomes diffused by means of the Arts.

The worship of the heavenly bodies & their supposed influence led the Egyptians, Chaldeans and other nations to study Astronomy, typified by the centre statues, the key stone to the composition.

Civilization is now presumed to have made considerable progress. Descending towards the Western angle of the pediment, is Mathematics; in allusion to science being now pursued on known sound principles. The Drama, Poetry and Music balance the group of the Fine arts, on the Eastern side, the whole composition terminating with Natural History of which such objects or specimens only are represented as could be made most effective in sculpture. [qtd. in Bryant 323]

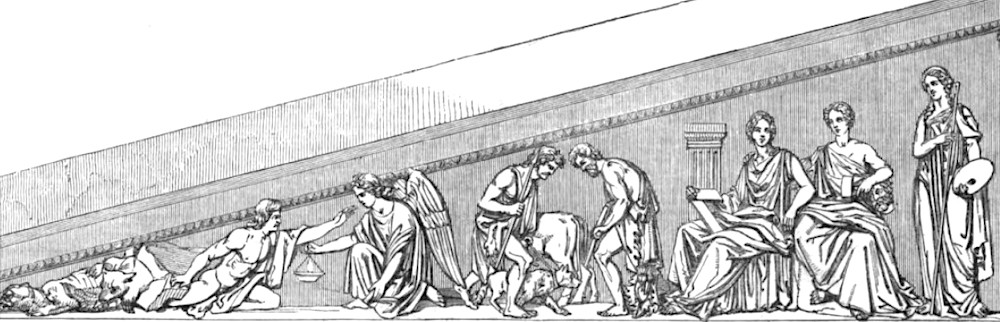

The left side of the pediment. Source: "The British Museum...."

Here, shown more clearly in the line drawing in Illustrated London News of the time, primordial man is shown emerging effortfully from a cleft rock, with an angel kneeling in front of him, holding a lamp (gilded in the original), and encouraging him. An agricultural scene follows, complete with dog wearing a collar. Mark Bryant considers the furthest figure on the left as "the best figure in the composition" (322), contrasting it with the passive Adam of Michelangelo's famous creation scene. Here, Westmacott's annotation actually reads, "Man redeemed from a savage state by Religion," but it is clear that he advances through his own struggles, even if under guidance. Then, after the hunting, tilling and labouring group, come the classical arts: both architecture and sculpture are represented with their instruments, architecture next to a column, and sculpture with her forearm resting on a carving.

The central figures in Westmacott's presentation design. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Source: "Drawing."

At the centre is Astronomy with her own instruments, holding a globe. Next to her on the left is Painting, holding a palette. On the other side, to the right, is Mathematics, followed by Drama holding a comic mask, Poetry with a writing tablet and a scroll, then Music with a harp.

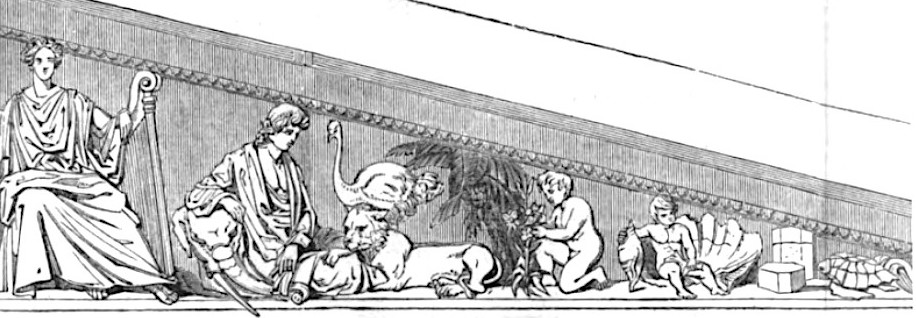

The right side of the pediment. Source: "The British Museum...."

To the right of Music, descending to the right edge of the pediemnt, and balancing primitive man's emergence from the rock on the far left, are Natural History exhibits. Plant specimens are being gathered, an elephant and other creatures can be seen, and on the furthest right, better shown in this simple line drawing than in the reproduction of Westmacott's coloured one, is a giant tortoise. This was in reference, apparently, to the one brought back by Darwin from the Galapogos Islands: when it died in 1837, Darwin had presented it to the museum (see Bryant 322).

The Artistry of the Pediment

For all its emphasis on the broad sweep of history, the pediment is quite novel in its artistry. The idea of filling a pediment with individual figures, all executed in the round, and placed continuously across the triangular space, was Greek rather than Roman in inspiration. Far from being conventional for English neoclassicism, this was a distinct form only recently noted, and first described” by Charles Robert Cockerell (see Bryant 317). It had been partially adopted at the Fitzwilliam Museum at Cambridge, in Charles Lock Eastlake's design for the pediment there, and at the Royal Exchange in London, where the sculptor was Westmacott's son, Richard Westmacott Jr. But in both cases, some carving had been done in relief. (In fact the British Museum pediment too has some relief work, though only for objects, not figures.)

Another interesting point about this work is the colour. Originally, as in Westmacott's own drawing, it was meant to have a blue background as well as some gilding. This early bid for polychromy was also in deference to the Greeks. It proved controversial in England, but, as Bryant says, what modern art critics (and the general public) perceived as overdone and grandiose, like the hefty, individual statues, or gaudy, like the application of colour, should actually be read as "a deliberate vocabulary of antique rigour and and severity" (319).

Interpreting the Pediment

Of equal interest is the general import of the composition. According to Eric Gidal, this "progressive iconography exemplifies both the foundational myth of Enlightenment Rationalism and Victorian imperialism," justifying "empirical classification and material appropriation" alike (11). This seems especially true when taking into account references in the poses of Architecture and Sculpture to figures in the Elgin Marbles (see Bryant 319).

Looking lower down the south front to the Trustee's seal, however, Gidal infers that the trustees themselves recognised that the museum has a larger function. Noting that the figure of Britannia was dropped from the seal, he finds the stress here on the "timeless and universal principles of classical thought." From this point of view, the museum can be seen as a "repository of eternal ideals" (14). Debate over the return of certain items to their countries of origin (notably the Elgin Marbles, to Greece) show that the tension between these various expressions of the British Museum's purpose continues to be felt to this day. [Click on all the images to enlarge them.]

Top photograph (2005) © George P. Landow. Other images and commentary added by the author. [You may use the photographs and black-and-white images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer or the person who scanned the images, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.] Westmacott's drawing and the view of its central figures come from one image downloaded from the British Museum website, of Museum object number 1887,0502.1. Although this is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC by-NC-SA 4.0) license, the Museum requires you to register before downloading it.

Related Material

- The British Museum

- The Elgin Marbles, Polychromy, and Ancient Greek Art as an Aesthetic Ideal

- Polychromy in the work of Baron Carlo Marochetti (1805-1867): Part I (of a three-part article)

Bibliography

"The British Museum, Pediment of the Principal Front." Illustrated London News. Vol. 20 (Jan-June 1852). Hathi Trust, from a copy in the University of California Library. Web. 14 September 2019: 427.

Bryant, Max. "'The Progress of Civilization': the pedimental sculpture of the British Museum” by Richard Westmacott." Sculpture Journal 25/3 (2016). 315-17.

"Drawing." British Museum. Web. 13 September 2019.

Gidal, Eric. Poetic Exhibitions: Romantic Aesthetics and the Pleasures of the British Museum. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 2001.

Last modified 26 February 2020