With the increase in letter writing stimulated by the Penny Post, Victorian letter-writing manuals rose in popularity. The Penny Post coincided with the Victorians’ growing interest in self-education, fueled, in part, by the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, which published educational pamphlets for the middle and working classes between 1826-48. This was also an age where the quality of a letter determined one’s character, and people considered penmanship a mark of breeding. Novels published throughout the nineteenth century illustrate both points. In Jane Austen’s Emma (1815), Mrs. Weston and many of her neighbors in Highbury form a “favourable” impression of Frank Churchill based solely on his writing his new stepmother a “handsome letter”: Austen confirms that “such a pleasing attention was an irresistible proof of his great good sense” (11). In George Eliot’s Middlemarch (1872), Caleb Garth informs Fred Vincy that he must improve his penmanship if he is to remain in his employ: “‘What’s the use of writing at all if nobody can understand it’” (611). Similar ideas about the art of polite correspondence and the importance of neat handwriting fill writing manuals of the day published on both sides of the Atlantic.

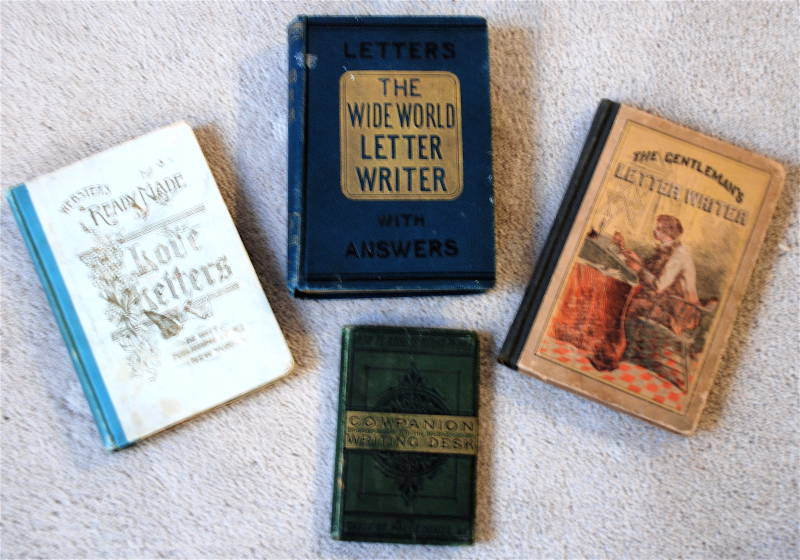

Left: These four manuals, printed in England and America, date from the mid to late nineteenth century, demonstrating the growth of writing manuals and suggest that lowering postage to a penny was not enough to promote literacy as postal reformers had prophesied.

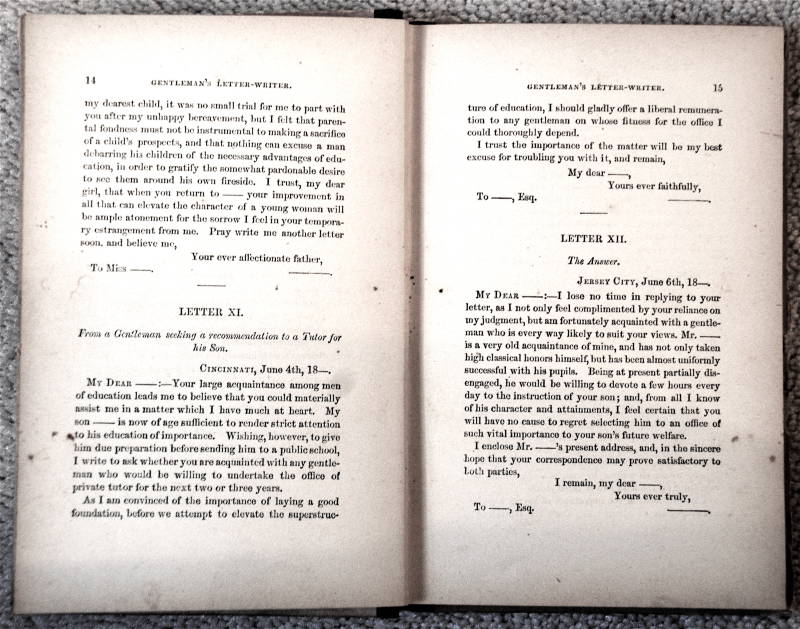

Right: The Gentleman's Letter Writer: This page shows a model letter from a gentleman seeking a tutor for his son and a reply a tutor might use in response to such a request. While today we can purchase books on how to construct a business letter or write a resum�, Victorian manuals like this include dozens of model letters and answers on topics including jobs, courtship, condolence, and congratulations. [Click on thumbnails for larger images.]

Widely circulated letter-writing manuals, such as The Universal Letter Writer and The Wide World Letter Writer, appeal to men and women and include dozens of model letters and appropriate responses on topics including how to apply for a job, accept or decline a position, send condolences, propose, accept an offer of marriage or cordially decline it, or declare a long undisclosed passion. While today we fear a paper trail and relish paper shredders, the Victorians had a predilection for committing important matters to writing. As nineteenth-century novels well illustrate, marriage proposals and acceptances by letter appear in, for example, George Eliot’s Middlemarch as well as Anthony Trollope’s The Eustace Diamonds (1871) and Kept in the Dark (1882), which includes a letter breaking off an engagement that closely resembles “From a Gentleman to a Lady, Confessing Change of Sentiment” from the The Wide World Letter Writer. Some manuals target specific audiences, such as the newly literate or the Victorian lady or gentleman, and still others focus exclusively on one type of letter. Titles of these volumes typically declare their intended audience or focus — e.g. A New Letter-Writer, for the Use of Gentlemen, Webster’s Ready-Made Love Letters. Pocket-sized manuals designed to keep in one’s writing desk include the aptly titled Companion to the Writing-Desk, which provides information on how to address letters (e.g. Royal Personages, the Nobility, civic authorities) as well as on the general art of composition.

Although we know Lewis Carroll as the creator of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), Carroll immersed himself in the world of letter writing and even authored a letter-writing manual. An avid letter writer, Carroll kept an accurate register of all the letters he wrote and received throughout his lifetime. He piggybacked on the popularity of his enduring Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by designing a letter-writing manual and a Wonderland postage stamp case marketed with it. Different from other period manuals, Eight or Nine Wise Words About Letter-Writing (1890) seems, in the words of Carroll’s biographer Morton Cohen, "practical, sensible, and tongue-in-cheek" (Biography 493). Carroll advises the writer to reread a letter before answering it; to affix the stamp and to address the envelope before writing the letter to avoid the "wildly-scrawled signature — the hastily-fastened envelope, which comes open in the post — the address, a mere hieroglyphic" (Eight or Nine 2-3); to write legibly; to avoid extensive apologies for not writing sooner; to use a second sheet of paper rather than to "cross" — "Remember the old proverb 'Cross-writing makes cross reading'" (16-17). Carroll even suggests where to store the postage stamp case: "this is meant to haunt your envelope-case, or wherever you keep your writing-materials" (37).

Letter-writing manuals helped writers take advantage of the opportunities for frequent communication now affordable to the larger public. To recall the words of Rev. T. Cooke in his preface to The Universal Letter Writer, “Letters are the life of trade — the fuel of love — the pleasure of friendship — the food of the politician — and the entertainment of the curious. To speak to those we love or esteem, is the greatest satisfaction we are capable of knowing; and the next is, being able to converse with them by letter” (vi). In an increasingly mobile and literate society, letter-writing manuals helped Victorians across social classes to seek employment, conduct business, hire and fire, give advice, declare their love, and “converse” with family and friends at times of rejoicing and mourning.

References

Austen, Jane. 1815. Emma. Ed. Lionel Trilling. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1957.

Carroll, Lewis. Eight or Nine Wise Words About Letter-Writing. 1890. Delray Beach, Fla.: Levenger Press, 1999.

Cohen, Morton N. Lewis Carroll: A Biography. New York: Knopf, 1995.

Companion to the Writing-Desk; or, How to Address, Begin, and End Letters to Titled. London: R. Hardwicke, 1861.

Cooke, Rev. T. The Universal Letter Writer; or New Art of Polite Correspondence. London: Milner and Company, c. 1850.

Eliot, George. Middlemarch. 1872. Ed. W. J. Harvey. New York: Penguin, 1976.

Golden, Catherine J. Posting It: The Victorian Revolution in Letter Writing. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2009.

A New Letter-Writer, for the Use of Gentlemen. Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, 1868.

Webster’s Ready-Made Love Letters. New York: De Witt, 1873.

The Wide World Letter Writer: Letters with Answers. London: Milner, n.d.

Last modified 16 June 2010