Excerpted with permission from Reformation, Revolution and Rebirth: The Story of the Return of Catholicism to Reading and the Founding of St James' Parish by John Mullaney and Lindsay Mullaney (Reading: Scallop Shell Press, 2012), pp. 112-146, and reformatted for the Victorian Web by Jacqueline Banerjee. Omissions of references to earlier chapters, or of more specifically local history material, are marked by [...]. All images come from the book, and reproduction rights belong to the authors or to those indicated in the credits. For more information about the book, please visit the Scallop Shell Press website.

The Principles of Architecture

Pugin begins his book The True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture, by first stating that design has to be "necessary for convenience, construction or propriety." Secondly, "all ornament should consist of enrichment of the essential construction of the building." These are the two principles by which he says "you may be enabled to test architectural excellence."

On reading his introduction, other words that come to mind, and which have been applied to Pugin's work, are firmness and delight; symmetry and economy. These in turn evoke the great principles of architecture: firmitas, utilitas and venustas, laid down in the first century BC, by the Roman architect, Vitruvius. Readers may have their own preferences on how best to translate these terms but the idea of firmitas or solidity is reflected in Pugin's commitment to construction whereas utilitas equates with his concept of propriety or convenience, which today we would call being "fit for purpose." Venustas (beauty) sits neatly with Pugin's definition of "ornament."

It is worth reproducing a few more quotes from Pugin's True Principles. They serve to give us a flavour of his approach to the practical work of designing a building. At one point he writes: "In pure architecture the smallest detail should have meaning or serve a purpose." Elsewhere he makes the contentious statement, especially with regard to St James': "it is in pointed architecture alone that these principles have been carried out."

I shall also consider "ornament" with reference to the three principles, looking at the techniques of construction, be they in stone, metal or timber.

In The True Principles Pugin treated each element of church design in order, starting with the columns and buttresses. I shall follow that same order here.

Columns and Buttresses

Principle: "It is evident that for strength and beauty, breaks or projections are necessary."

Even in such a small church as St James', Pugin adheres to this principle. He breaks the lines of the long north and south walls by a regular series of five bays consisting of alternating windows and simple buttresses. The vertical line is compensated for by the use of equally regular horizontal string-courses. These serve not only as ornamentation but follow the principle of "utility," by virtue of their weathering function. The bottom course, or plinth, is splayed, or bevelled, to take the water run-off away from the base. The whole achieves an effect appropriate to the scale of the building or, as Pugin would argue, follows the principle of "propriety." It is worth commenting that in his only other Norman Romanesque church, at Gorey in Ireland, the base does not have this feature; the wall extends down to ground level.

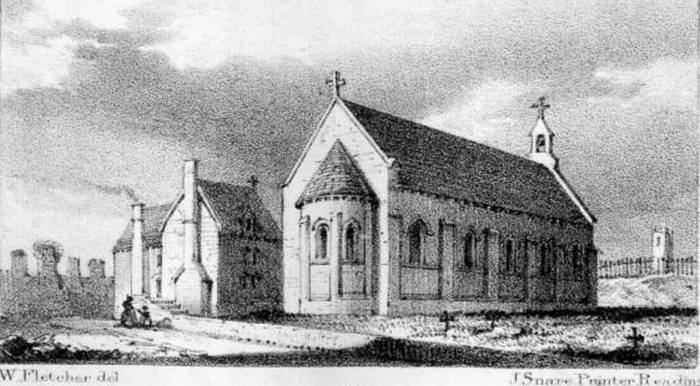

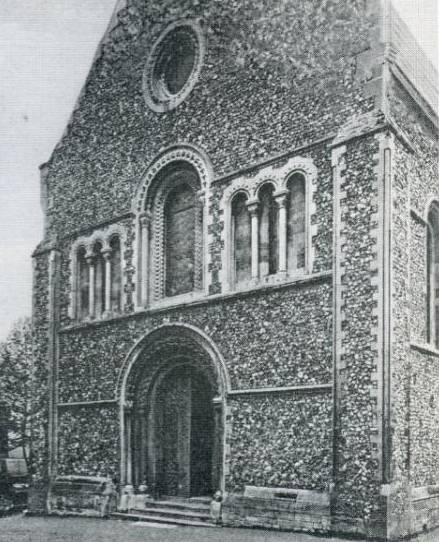

Left: Fig. 1. Courtesy of Reading Library. Right: Fig. 2. Courtesy of St James' Church

Note the use of "clamped" or "clasping" buttresses at the corners of the west end (Fig 2). The earliest drawing we have (Fig 1) does not seem to show a clamped buttress at the east end. Subsequent alterations have made it difficult to establish what the eastern buttresses were like. However the existing eastern corner buttresses are much wider than those either at the west end or along the walls. Other contemporary sketches indicate this may have been the case when the church was first built.

Photographs of the original frontage clearly show this type of buttress at the west end, along with the string courses and splays mentioned above. There is another view of St James' in Reading Library, again attributed to W. Fletcher, from Kennet Mouth looking across at the newly completed Great Western railway embankment. This is a very rough sketch but, from what can be made out, it supports the theory that the buttresses at the east end match those at the west in style but are in fact larger in width and depth.

If next we turn to examine the ashlar dressings of the buttresses in figure 2, we note the use of irregularly sized limestone corner stones or quoins. Pugin argues that if these are the same size "the eye is carried from the line of the jamb to them." The same maxim is applies to window or door jambs.

He claims that a regular pattern to the quoins has the unfortunate effect of drawing the viewer's attention away to the peripheral parts of the structure, in other words outwards. So here, for example, the eye would be drawn towards the quoins and the buttresses and away from the intended foci of the building.

Pugin further states that small sized stonework not only makes construction stronger but also maintains the proportions, which would be destroyed by larger masonry elements. In addition he claims that stones in ancient buildings were not only small but "also very irregular in size so that the jointing might not appear a regular feature and by its lines interfere with those of the building."

The West Front

So what is the focus of attention, what was Pugin asking the building to do and what reaction does he expect from the viewer? He is explicit in his writings that a church exists for the glory of God and to connect man with his Creator.

Pugin wrote that "the history of architecture is the history of the world." All forms of architecture may be "perfect expressions" but they are perfect expressions of "imperfect systems." Only true Christian worship of the one true Christian God is the "perfect system," and pointed architecture is the culmination of that development, "the crowning result," of all previous Christian forms of architecture. He attacks the architectural changes at the Reformation in the 16th century as not a "matter of mere taste, but a change of soul."

Here lies a clue, in his own writings, as to Pugin's thoughts about designing in a non-pointed style. He claims that "previous to this period architecture had always been a correct type of the various systems." Tie this in with his evolutionary view of Christian architecture and we can see how he could justify the use of the Norman Romanesque style. It should be remembered that Pugin spent much of his early life staying with relatives in Northern France and made many visits to the great churches of Normandy. He was as well versed in the development of architecture in Northern Europe in the Middle Ages as anyone could be; a claim he certainly made for himself.

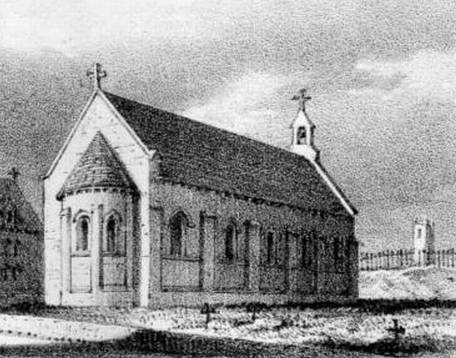

I leave the readers to come their own conclusion about the focus of attention at the west end of St. James'. To me, however, there are two: the entrance to a holy place and the surmounting bellcote, which originally supported a cross.

The eye is drawn inwards and upwards. Our immediate focus is the great door, inviting the viewer into the home of the "sacred mysteries." The idea of the pointed arch is to facilitate and reflect an ever upward or heavenly movement. The fact that Pugin achieves this effect with the use of rounded arches displays his architectural skills. The sketch in Marianna Frederica Cowlsade's book fully confirms this conclusion. The effect is completed by the eye being drawn first to the bell-cote and finally to the cross. It is important to note that there is a matching cross surmounting the east gable."

Whether Mangan, the architect of the 1926 alterations, respected or contradicted Pugin's design is a matter of opinion. Bringing the lower half of the west gable forward certainly gave the church greater depth and so more room. But was this at the cost of sacrificing propriety, convenience, construction, and so beauty, to utility? Would Pugin have considered the design as inconsistent, and thus undesirable?

Pugin's heading, and mine, to this section mentions "columns." I shall look at columns and pillars later when considering the west door in detail.

Pinnacles

Principle: "Pinnacles should be regarded as answering a double intention, both mystical and natural."

Pugin says that pinnacles are not ornamental excrescences. They are not there merely for picturesque effect, but they serve two purposes, mystical and natural. St James' does not possess pinnacles but it does have a bellcote which to some extent served the same mystical intention. As we have just seen, the use of the cross surmounting the east gable and the bellcote at the west end, as in the drawing, serves both purposes: "Their mystical intention, like other vertical lines in Christian architecture, is an emblem of the Resurrection," and draws the viewer's gaze ever upwards. Unfortunately the bellcote cross was later removed. Compare the two pictures below.

The bellcote draws the eye upwards, pointing like a finger to heaven. It is symbolic but also practical in that it houses the bell. For Pugin the bell is not a mere embellishment. It may be an ornament but only in so far as it fulfils its liturgical purpose. It is the means by which "the faithful may be called to their devotions." As such it is placed in an appropriate tower or belfry. In the case of St James', the bellcote, as we have seen, is highly visible and was originally crowned with a stone cross. Because of its height it is difficult to appreciate the care taken in its construction. Closer examination shows that the detail of the bellcote and its mouldings are consistent with every aspect of Pugin's Principles.

It is worthwhile recalling that under the 1791 Catholic Relief Act, bells were explicitly forbidden to Catholic Chapels. They were only allowed following the 1829 Catholic Emancipation Act. Their symbolism was therefore understood by Catholics and non-Catholics alike and enshrined in the law of the land. It is worth noting that the report in The Tablet explicitly mentions this important feature.

Related Material

- 1. A. W. N. Pugin's First Church, St James', Reading

- 2. The Original Design and the Norman Romanesque Style

- 4. The True Principles and Their Application to St James' (Part 2)

- 5. The True Principles and Their Application to St James' (Part 3)

- 6. Bibliography and Sources

Last modified 21 December 2012