Suffering him to clasp her round the waist, as they moved slowly down the dim wooden gallery — Fred Barbard's illustration for Dickens's The Cricket on the Hearth in Christmas Books, 104. Engraved by one of the Dalziels, and signed "FB" lower right. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Context of the Illustration

Oh, Shadow on the Hearth! Oh, truthful Cricket! Oh, perfidious Wife!

He saw her, with the old man — old no longer, but erect and gallant — bearing in his hand the false white hair that had won his way into their desolate and miserable home. He saw her listening to him, as he bent his head to whisper in her ear; and suffering him to clasp her round the waist, as they moved slowly down the dim wooden gallery towards the door by which they had entered it. He saw them stop, and saw her turn — to have the face, the face he loved so, so presented to his view! — and saw her, with her own hands, adjust the lie upon his head, laughing, as she did it, at his unsuspicious nature!

He clenched his strong right hand at first, as if it would have beaten down a lion. But opening it immediately again, he spread it out before the eyes of Tackleton (for he was tender of her, even then), and so, as they passed out, fell down upon a desk, and was as weak as any infant. [British Household Edition, "Chirp the Second," 102]

Commentary

Barnard's crucial illustration in "Chirp the Second" of A Cricket on the Hearth shows the youthful and blithe couple observed by Tackleton and Peerybingle (left rear). Dot and Edward Plummer are innocently discussing May's forthcoming marriage to Tackleton. However, the mischief-making toymaker attempts to make John believe that the reappearance of the handsome youth — disguised as an elderly traveller — has rekindled an old flame for John's much younger wife.

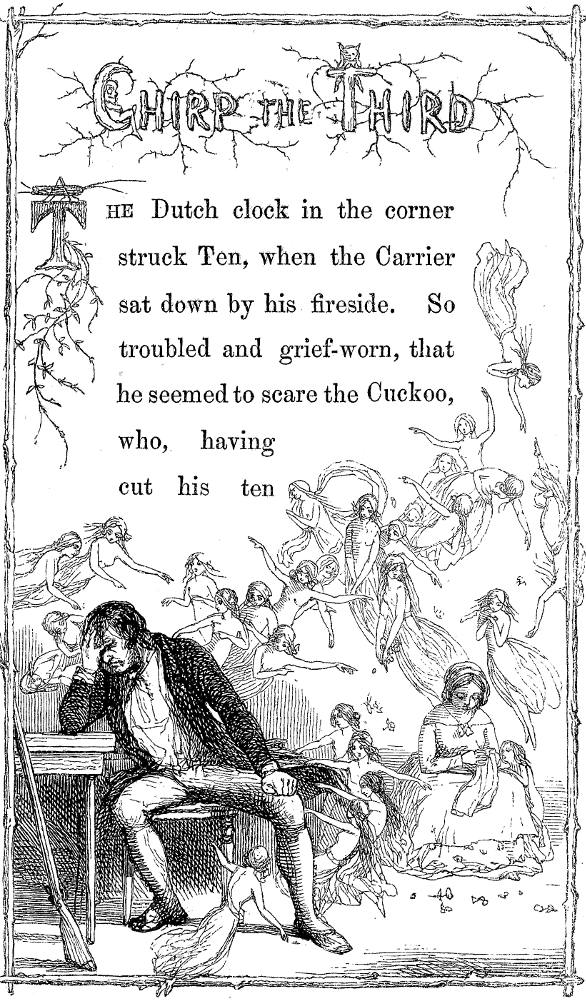

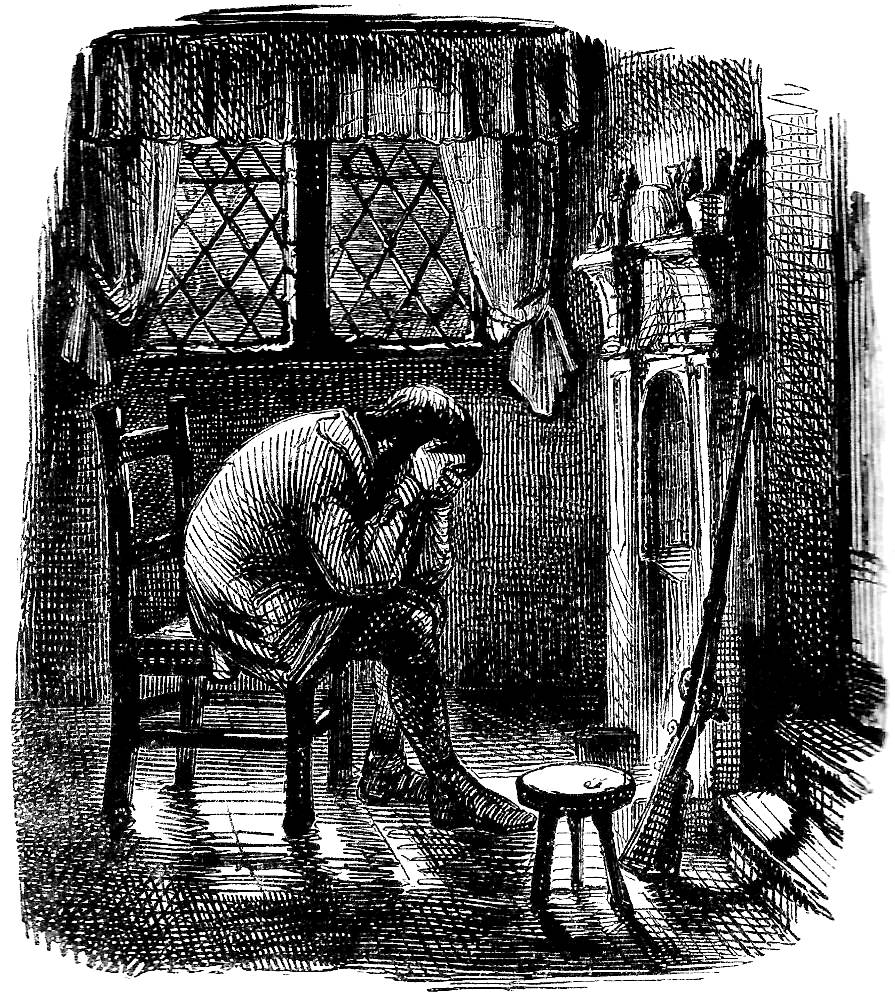

The Barnard and Abbey Household Edition illustrations depict the central issue of The Cricket on the Hearth: in a confusion typical of domestic melodrama, is John's misinterpretation of this scene in the "ware-room" or storeroom of Tackleton's toy manufactory about to result in the husband's murdering his young wife and her putative lover? The shotgun posed near John in Doyle's and Leech's illustrations suggest the possibility of violent action. Seeing his wife with a handsome young man, the supposed elderly stranger to whom he earlier gave a ride in his carrier's van, John incorrectly concludes that his wife is guilty of adultery. Acting the role of Satanic tempter, the misanthropic Tackleton seems to feel that showing John such a sight will prompt him to violence, but John surprises him by refusing to exact vengeance. In Abbey's rather more dramatic scene, John vents his anger and frustration on Tackleton himself. In contrast, the illustrators of the 1845 edition showed the consequences of this disclosure scene, for Richard Doyle shows an anguished husband wrestling emotionally before the cold hearth with his feelings of rejection and betrayal.

Barnard's illustration of putative adultery and the husband's reaction complemented in plates by other 19th c. illustrators.

Three illustrations of John's moral and emotional conflict: Left: Doyle's Chirp the Third (1845). Centre: Leech's John's Reverie (1845). Right: Luigi Rossi's "dark plate" version of the same scene, but foregrounding the watchers: What Tackleton Revealed to the Carrier (1912).

Above: Abbey's dramatic wrestling match between John and Tackleton: "Listen to me!" he said. "And take care you hear me right" (1876).

The Leech illustration, somewhat less refined than Doyle's version of John's internal conflict, specifically situates the husband's contemplation of a barren future before the familial hearth, now shrunken from its previous proportions. Leech may be implying that John's doubting his younger wife's fidelity has diminished the hearth as a symbol of the power of the domestic ideal to which the middle-aged carrier has previously subscribed unquestioningly. The fireplace offers neither heat nor light, reflecting John's own bleak assessment of his family's solidarity. Leech, as in The Dance, has dressed John in a smockfrock, indicative of his rural and working class origins and occupation, rather than in the middle-class garb of the same character in Doyle's "Chirp the Third." The conspicuous stool, highlighted by moonlight and positioned by John's right foot and immediately in front of his shotgun, sits empty, a reminder of the intimate relationship he previously enjoyed with the diminutive Dot.

Whereas Dickens's original illustrators emphasized the supernatural dimension of the story by surrounding the characters with goblin or fairy presences, as in Doyle's Chirp the Third (in which the carrier's agony is reflected by the agitation of the fairies above him and to the right), Barnard (with this exception of his fairy cricket title-page vignette) and Abbey eliminate the supernatural altogether. And, indeed, both Household Edition illustrators seem to have felt that the challenge to John Peerybingle's peace of mind posed by his wife's supposed infidelity was important enough to be underscored by a pertinent illustration. Since Dickens supplies no details about the contents of "the long narrow ware-room" (102), Barnard has supplied such toys as Dickens has mentioned that Bertha and her father produce: four rockinghorses (left), a yacht, and a substantial dolls' house (right). Although Dot wears the same cap and gown as in John Peerybingle's Fireside, Barnard has dressed Edward (wig in hand) in an elegant Regency costume that seems inconsistent with what one would expect an elderly traveller to be wearing — although, indeed, Dickens's description of the Old Stranger's clothing (including "gaiters" [83], and "His garb was very quaint and odd — a long, long way behind the time") hardly suggests the costume that Barnard has given Edward in this scene.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and his Original Illustrators. Columbus: University of Ohio Press, 1980.

Cook, James. Bibliography of the Writings of Dickens. London: Frank Kerslake, 1879. As given in Publishers' Circular The English Catalogue of Books.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

_____. The Cricket on the Hearth. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

_____. The Cricket on the Hearth. Illustrated by John Leech, Richard Doyle, Daniel Maclise, Clarkson Stanfield, and Edwin Landseer. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1845.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. London: Educational Book, 1912.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004.

Parker, David. "Christmas Books and Stories, 1844 to 1854." Christmas and Charles Dickens. New York: AMS Press, 2005. 221-282.

Patten, Robert L. Charles Dickens and His Publishers. University of California at Santa Cruz. The Dickens Project, 1991. Rpt. from Oxford U. p., 1978.

Slater, Michael. "Introduction to The Cricket on the Hearth." Dickens's Christmas Books. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1971. Rpt., 1978. II: 9-12.

Slater, Michael. "Notes to The Cricket on the Hearth." Dickens's Christmas Books. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1971. Rpt., 1978. II: 363-364.

Solberg, Sarah A. "'Text Dropped into the Woodcuts': Dickens' Christmas Books." Dickens Studies Annual 8 (1980): 103-118.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Created 2 August 2012

Last modified 24 April 2020