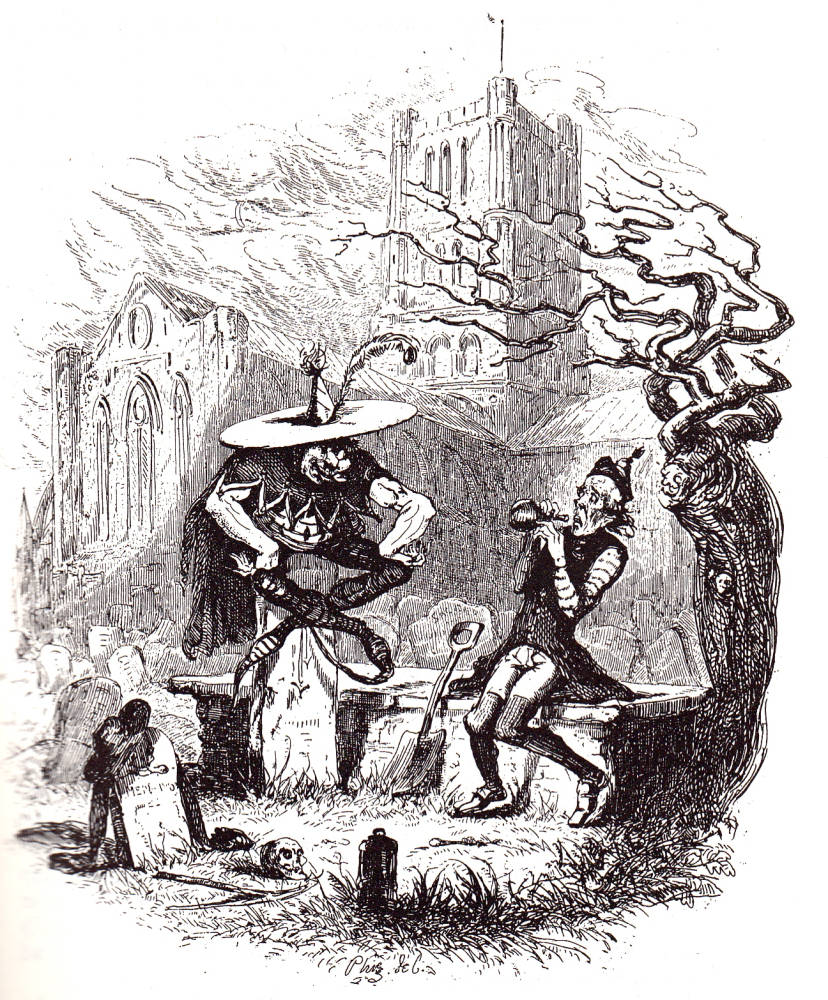

“And now,” said the goblin king, “show the man of misery and gloom a few of the pictures from our own great store house.” — in The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, for Chapter XXIX, Instalment Ten (January 1837), based on Phiz's steel engraving The Goblin and The Sexton, page 247. 12.7 cm high by 10.7 cm wide (5 by 4 ½ inches), vignetted. Onwhyn issued this "extra" illustration on September 30, 1837.

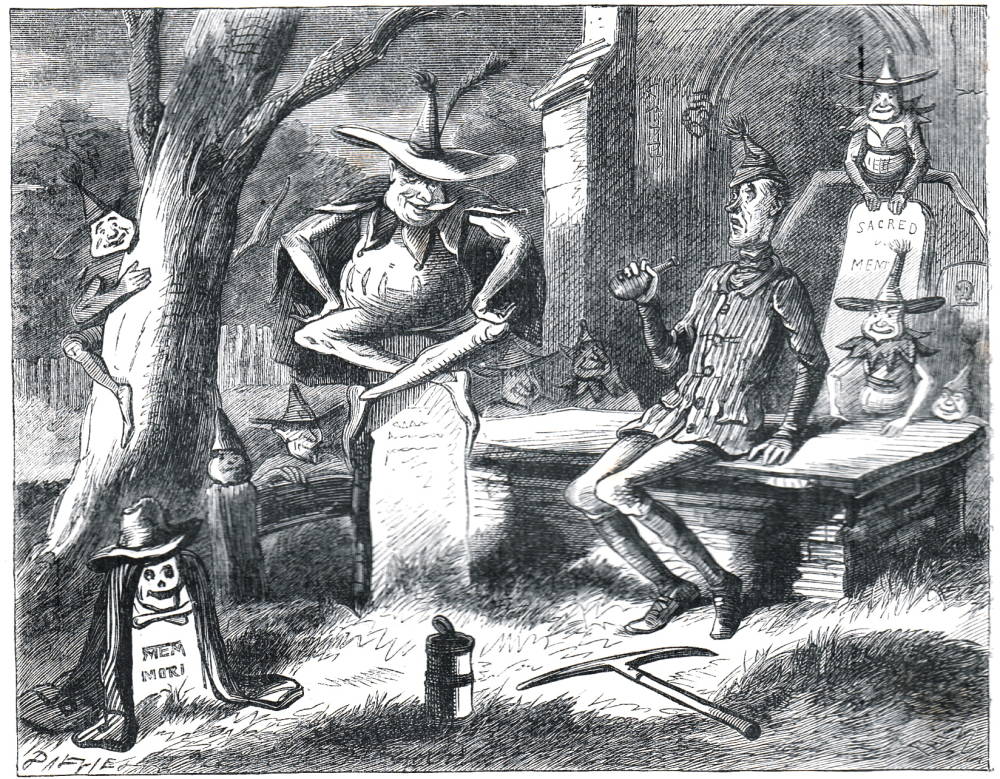

Passage Illustrated: The Lamentable Sight that the Goblin King shows Gabriel Grubb

‘“And now,” said the king, fantastically poking the taper corner of his sugar-loaf hat into the sexton’s eye, and thereby occasioning him the most exquisite pain; “and now, show the man of misery and gloom, a few of the pictures from our own great storehouse!”

‘As the goblin said this, a thick cloud which obscured the remoter end of the cavern rolled gradually away, and disclosed, apparently at a great distance, a small and scantily furnished, but neat and clean apartment. A crowd of little children were gathered round a bright fire, clinging to their mother’s gown, and gambolling around her chair. The mother occasionally rose, and drew aside the window-curtain, as if to look for some expected object; a frugal meal was ready spread upon the table; and an elbow chair was placed near the fire. A knock was heard at the door; the mother opened it, and the children crowded round her, and clapped their hands for joy, as their father entered. He was wet and weary, and shook the snow from his garments, as the children crowded round him, and seizing his cloak, hat, stick, and gloves, with busy zeal, ran with them from the room. Then, as he sat down to his meal before the fire, the children climbed about his knee, and the mother sat by his side, and all seemed happiness and comfort.

‘But a change came upon the view, almost imperceptibly. The scene was altered to a small bedroom, where the fairest and youngest child lay dying; the roses had fled from his cheek, and the light from his eye; and even as the sexton looked upon him with an interest he had never felt or known before, he died. His young brothers and sisters crowded round his little bed, and seized his tiny hand, so cold and heavy; but they shrank back from its touch, and looked with awe on his infant face; for calm and tranquil as it was, and sleeping in rest and peace as the beautiful child seemed to be, they saw that he was dead, and they knew that he was an angel looking down upon, and blessing them, from a bright and happy Heaven. [Chapter XXIX, “The Story of the Goblins who stole the Sexton,” 247]

Commentary: The Goblin King Presents Scenes from Life

Right: Phiz's original January 1837 version of the graveyard scene in the Tenth Instalment (Chapters 27, 28, and 29).

In The Goblin and the Sexton (in the January 1837 instalment), published eight months before Onwhyn's "unofficial" complement to the main program, Phiz had offered a delightful model for the "extra" illustrator. But Onwhyn humanizes the sexton as Phiz had not done, and appeals to sentimentality rather than a taste for the whimsical and bizarre. We see one of those sights which, like the scenes that Marley's Ghost and the three Spirits of Christmas show Scrooge, changes the course of Grubb's life. Dickens's model is, of course, Washington Irving's "Rip Van Winkle" (1819) from The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent.

Unlike the other interpolated tales in the picaresque novel, “The Story of the Goblins Who Stole a Sexton” is a self-contained chapter, although once again narrated by one of the characters whom Pickwick meets, Mr. Wardle. Phiz had already, months before, brilliantly set the scene (a country churchyard in the late afternoon) and introduced the two principal characters: the physically distorted, jocular Goblin King, and the curmudgeonly grave-diggger, Gabriel Grubb, suitably named for the Archangel from "The Book of Daniel" and "The Gospel According to St. Luke" who will announce to Mary that she will give birth to the Son of God. But his surname is an utter contrast, suggesting death and decay rather than miraculous birth, for a grub is an insect that inhabits the soil of cemeteries in legions. So whimsical a Christian and surname as well as the bizarre antics of the goblins suggest we have entered the magical, comical world of pantomime. And Onwhyn's imaginative treatment of the sights to which the Goblins subject Grubb in their underground theatre-cavern reinforces this impression.

In this highly imaginative treatment of the text, the goblins form both an interactive audience and a proscenium arch. They sit in the darkness, watching the action unfold "onstage," which to us today looks more like a gigantic video screen. As the Goblin King in his huge hat and pointed shoes points at the young mother and her three children in front of the fireplace in the humble parlour, Grubb seems shocked: his mouth open, he holds up a hand as if the sight is too emotional, too sad to be endured. Even as the kettle boils on the fire, he learns that the infant clambering up his mother is destined to die. Already at this point, then, the chief spirit seems to have foretold the child's death; the very youngest of the three will die, and leaving parents and siblings to grieve — and remember him. This is the aspect of his vocation that Grubb has never before considered.

Each goblin responds uniquely, and no two lesser goblins among the fifteen in the proscenium frame are alike. Like an audience full of children accompanied by the odd parent at a Christmas pantomime each is both physically and especially facially an individual, but each is fully engaged in the onstage action, except for the animated stool (left, under the Goblin King) who studies Grubb's reaction to their "entertainment" in the theatrical cavern beneath the cemetery.

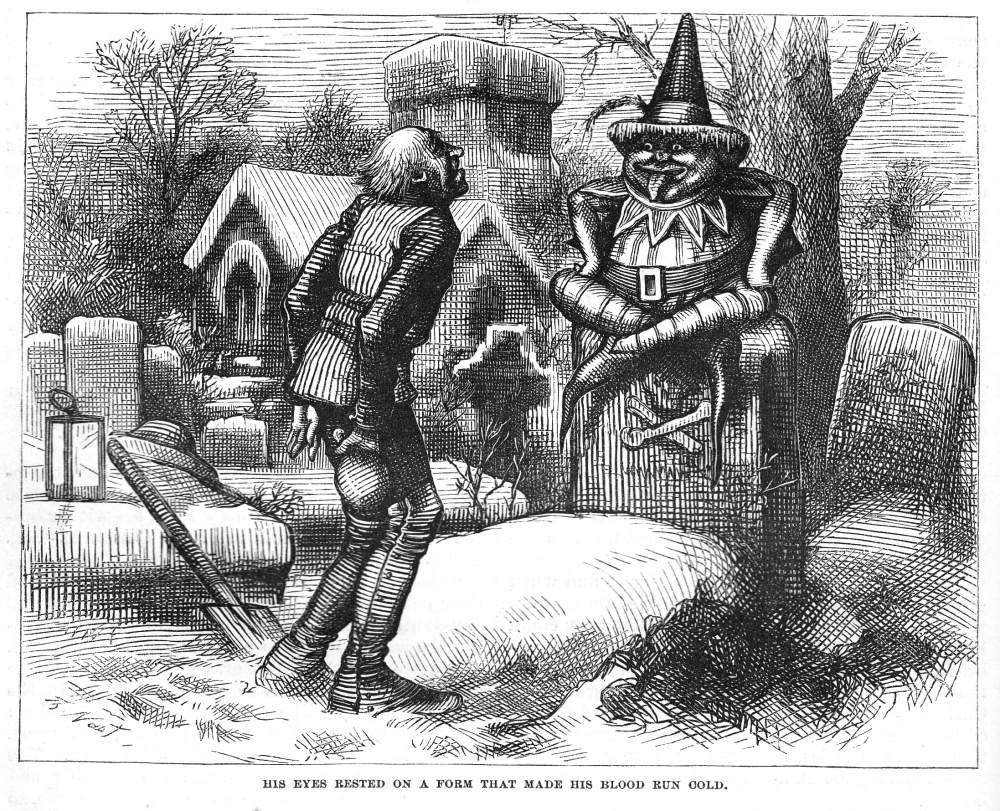

The Peculiar Goblin King in the British and American Household Editions (1873-74)

Left: Phiz's British Household Edition woodcut reworks his original 1837 steel engraving as Seated on an upright tombstone, close to him, was a strange, unearthly figure (Ch. XXIX, 1874). Right: The American edition's illustration by Thomas Nast that gives us a rather more rigid, caricatural sexton, His eyes rested on a form that made his blood run cold (1873). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

The History of Pantomime

- The Development of Pantomime, 1692-1761

- Victorian Pantomime

- Joseph Grimaldi, satire, and pantomime

- Dickens's The Christmas Books, Plays, and the Pantomime

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL or credit the Victorian Web in a print document.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Robert Seymour, Robert Buss, and Phiz. London: Chapman and Hall, November 1837. With 32 additional illustrations by Thomas Onwhyn (London: E. Grattan, April-November 1837).

_______. The Pickwick Papers. Illustrated by Thomas Nast (1873) and Phiz (1874). The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874; New York: Harpers and Brothers, 1873. Vol. 6.

Titley, Graham D. C. "Thomas Onwhyn: a Life in Illustration (1811-1886)." Pearl. University of Plymouth (2018-07-12).

Created 20 February 2024