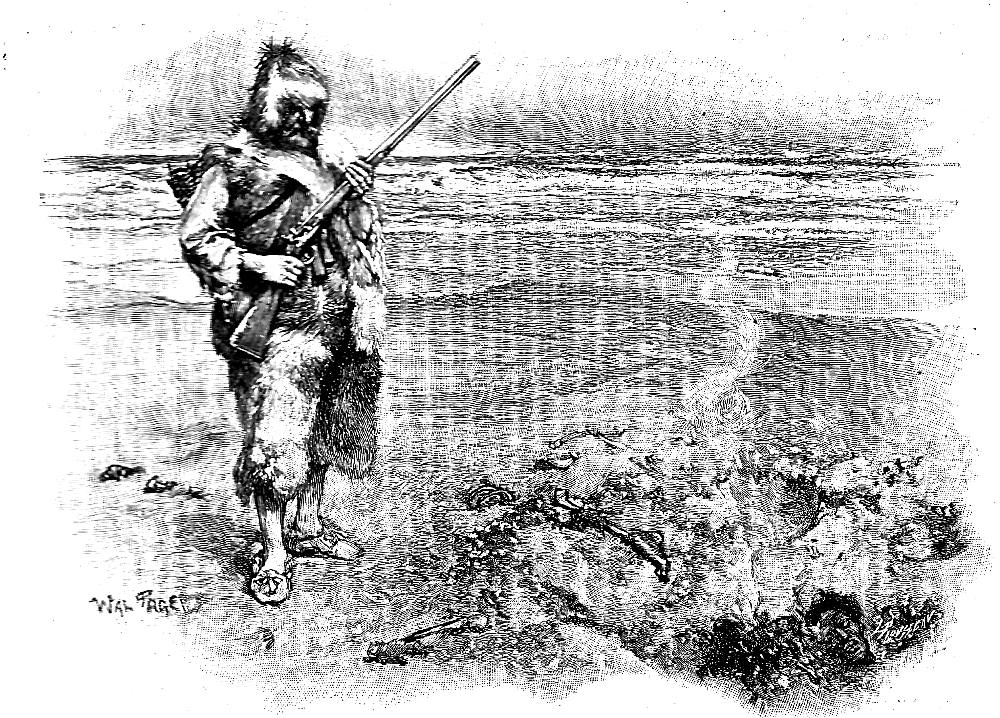

A Place where there had been a fire made (p. 114) depicts Crusoe in his "island" garb of goatskins surveying dispassionately the remnants of the grisly feast. Amidst the smoking embers we may discern — as he does — a severed foot and a leg bone. Despite his growing anxiety about unwanted visitors to his island, Crusoe continues his survey of the island, supplementing his over-the-shoulder wicker basket with rifle and ammunition. Top of page 120, vignetted: 9 cm high by 12 cm wide, signed "Wal Paget" in the lower left-hand quadrant. Running head: "Plans Against the Savages" (p. 121).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated: The Aftermath of the Cannibals' Feast

When I was come down the hill to the end of the island, where, indeed, I had never been before, I was presently convinced that seeing the print of a man's foot was not such a strange thing in the island as I imagined . . . .

When I was come down the hill to the shore, as I said above, being the SW. point of the island, I was perfectly confounded and amazed; nor is it possible for me to express the horror of my mind at seeing the shore spread with skulls, hands, feet, and other bones of human bodies; and particularly I observed a place where there had been a fire made, and a circle dug in the earth, like a cockpit, where I supposed the savage wretches had sat down to their human feastings upon the bodies of their fellow-creatures.

I was so astonished with the sight of these things, that I entertained no notions of any danger to myself from it for a long while: all my apprehensions were buried in the thoughts of such a pitch of inhuman, hellish brutality, and the horror of the degeneracy of human nature, which, though I had heard of it often, yet I never had so near a view of before; in short, I turned away my face from the horrid spectacle; my stomach grew sick, and I was just at the point of fainting, when nature discharged the disorder from my stomach; and having vomited with uncommon violence, I was a little relieved, but could not bear to stay in the place a moment; so I got up the hill again with all the speed I could, and walked on towards my own habitation. [Chapter XII, "A Cave Retreat," page 118: running head, "A Cannibal Orgie"]

Commentary

Paget has chosen a difficult scene to realise since as a realist his impulseis to provide realistic detail, but detailing the remnants of the cannibals' feast would certainly have transcended the bounds of goodtaste. Paget describes the protagonist's apparent fascination as well as his disgust in viewing a swevered foot and a leg bone amidst the unrecognizable detritus. Neil Heims (1983) relates Crusoe's abhorrence of the cannibalism by the indigenous population of the mainland opposite the island with his previous involvement in the slave trade, an equally abhorrent practice that treats human beings as cattle:

The confounding irony which reveals a serious identity between Crusoe and

the cannibals, however, and accounts for the split the fable effects between them, and

for his strong antagonism to them, is that Crusoe set out on the adventure that cast him

upon the island for twenty-eight years in order to be a trafficker in Negro slaves. The

savagery of this act of consuming and devouring, in order to be denied for the sake of

the European conscience, was displaced onto the blacks themselves by inventing a fable

that focuses on the more blatant savagery of a simpler cannibalism attributed to them. In

Crusoe has already discovered the remains of the cannibals' beach-fire and grisly feasting several pages earlier, and is now making defensive arrangements by carrying two pistols, a broad-sword in his belt.Throughout this sequence, Crusoe's dog accompanies him — and then disappears from the narrative-pictorial program after Crusoe's salvaging cargo from the wreck of the Spanish ship, paving the way for the appearance of Friday:"I was now in the twenty-third year of my residence. . . . My dog was a pleasant and loving companion to me for no less than sixteen years of my time, and then died of mere old age"(Chapter XIII, "The Wreck of a Spanish Ship," page 129).Although the dog is still very much alive at this point, Paget has intensified the reader's appreciation of Crusoe's sense of isolation by not including the dog in this or the next three frames. The running head, "A State of Siege" (129) underscores Crusoe's disturbed mental state after his discovery of the footprint on the beach.

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Associated Scenes from the 1863-64 Sequence

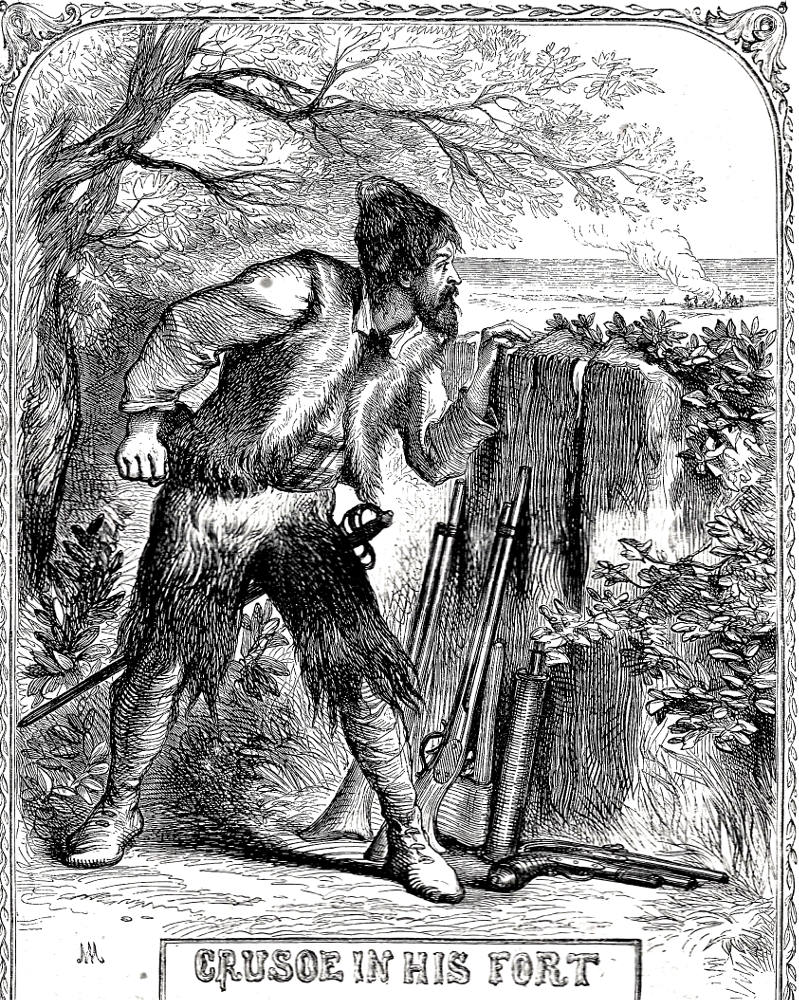

Above: The earlier Cassell's illustrations communicating Crusoe's heightened vigilance after the discovery of the footprint: Crusoe on the Look-out on the Hill and Crusoe in his Fort. Understandably, previous illustrators have avoided the scene of the castaway's discovering the grim feast's remains. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

References

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Of York, Mariner. As Related by Himself. With upwards of One Hundred and Twenty Original Illustrations by Walter Paget. London, Paris, and Melbourne: Cassell, 1891.

Heims, Neil. "Robinson Crusoe and the Fear of Being Eaten." Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 19, Issue 4 (December 1983). Pp. 190-193. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://search.yahoo.com/&httpsredir=1&article=2528&context=cq

Last modified 1 May 2018