Lay the dead man, with his stark and rigid face turned upward to the sky [Page 274] by Charles Stanley Reinhart (1875), in Charles Dickens's The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby, Harper & Bros. New York Household Edition, for Chapter L. 8.9 x 13.7 cm (3 ½ by 5 ⅜ inches), framed. Running head: "Early Morning" (275). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated: Sir Mulberry shoots Verisopht in a Duel

After a pause, and a brief conference between the seconds, they, at length, turned to the right, and taking a track across a little meadow, passed Ham House and came into some fields beyond. In one of these, they stopped. The ground was measured, some usual forms gone through, the two principals were placed front to front at the distance agreed upon, and Sir Mulberry turned his face towards his young adversary for the first time. He was very pale, his eyes were bloodshot, his dress disordered, and his hair dishevelled. For the face, it expressed nothing but violent and evil passions. He shaded his eyes with his hand; grazed at his opponent, steadfastly, for a few moments; and, then taking the weapon which was tendered to him, bent his eyes upon that, and looked up no more until the word was given, when he instantly fired.

The two shots were fired, as nearly as possible, at the same instant. In that instant, the young lord turned his head sharply round, fixed upon his adversary a ghastly stare, and without a groan or stagger, fell down dead.

"He’s gone!" cried Westwood, who, with the other second, had run up to the body, and fallen on one knee beside it.

"His blood on his own head," said Sir Mulberry. "He brought this upon himself, and forced it upon me."

"Captain Adams," cried Westwood, hastily, "I call you to witness that this was fairly done. Hawk, we have not a moment to lose. We must leave this place immediately, push for Brighton, and cross to France with all speed. This has been a bad business, and may be worse, if we delay a moment. Adams, consult your own safety, and don’t remain here; the living before the dead; goodbye!"

With these words, he seized Sir Mulberry by the arm, and hurried him away. Captain Adams — only pausing to convince himself, beyond all question, of the fatal result — sped off in the same direction, to concert measures with his servant for removing the body, and securing his own safety likewise.

So died Lord Frederick Verisopht, by the hand which he had loaded with gifts, and clasped a thousand times; by the act of him, but for whom, and others like him, he might have lived a happy man, and died with children’s faces round his bed.

The sun came proudly up in all his majesty, the noble river ran its winding course, the leaves quivered and rustled in the air, the birds poured their cheerful songs from every tree, the short-lived butterfly fluttered its little wings; all the light and life of day came on; and, amidst it all, and pressing down the grass whose every blade bore twenty tiny lives, lay the dead man, with his stark and rigid face turned upwards to the sky. [Chapter L, "Involves a serious Catastrophe," 275]

Commentary: Not the Duel but its Consequences

In Dickens's text, the actual duel is just a matter of a moment: two shots ring out almost simultaneously and young Lord Frederic Verisopht, in what has been the most noble act of his short and otherwise frivolous life, dies instantly. And Sir Mulberry Hawk suddenly finds himself fleeing to the Continent to avoid a murder charge. The approach that Reinhart has taken to his subject much resembles that taken by the other Household edition illustrator in the Chapman and Hall volume: although Barnard's treatment involves a full-page panorama, both pictures show a handsome, well-dressed corpse stretched out in a meadow, with the River Thames in the background. The deadman's top-hat, the signifier of his social status, and his handkerchief lie beside him on the grass. However, Reinhart emphasizes the grass and trees surrounding Verisopht, and makes the body a much larger part of the composition. Whereas Barnard has the newly risen sun flooding the meadow with searing light and only suggests the grass as he makes the sky almost half of the picture, Reinhart creates a sense of mystery in the deep shadows at the rear, where already the carriage containing the seconds and the victor is rattling off.

Commentary: "Fashionable" duelling had been outlawed by the 1870s.

The first duel in Great Britain involving pistols rather than rapiers was fought at Tothill Fields, London, in 1711 between Colonel Richard Thornhill and Sir Cholmley Deering, but such affairs of honour between military officers and aristocrats rarely involved firearms until the early 1760s. Such scenes occur regularly in novels set in the eighteenth century, but far less frequently in Victorian novels with contemporary settings since duelling was officially outlawed in 1819. In fact, from the seventeenth century onward most European nations had attempted to ban duelling, and replace it (when necessary) with litigation. By the time that Dickens was writing this instalment of Nicholas Nickleby in 1839, duelling had definitely fallen out of favour even among the aristocracy, in part thanks to a concerted effort by Prince Albert and the Duke of Wellington to change both the law and society's attitudes. The last duel officially recorded between Englishmen in the United Kingdom occurred on the beach near Portsmouth on 20 May 1845. Prior to the nineteenth century, an officer or a "gentleman" risked social ostracism for not issuing a challenge when insulted, or for failing to respond to such a challenge. By the time that Verisopht and Hawk met on the field of honour such affairs had to be managed surreptitiously since killing another in a duel was legally judged homicide. However, an interesting coincidence is that the very last duels known to have occurred on British soil involved a pair of French political refugees, Lieutenant Hawkey and Emmanuel Barthélemy, in 1852. Both were tried for murder.

Other Duelling Scenes from Various Victorian Novels (1841-64)

- Phiz's The Duel from Davenport Dunn (February 1858)

- Cruikshank's The Duel in Tothill Fields from The Miser (July 1842)

- Phiz's Sword Play from The Spendthrift (April 1855)

- Phiz's The Duel on Crabtree Green from Mervyn Clitheroe (December 1857)

- Walker's The Last Moments of the Count of Saverne from The Cornhill Magazine (April 1864)

- Cattermole's Sir John Chester's End from Barnaby Rudge (November 1841)

Parallel Illustrations from Other Editions (1839, 1875, and 1910)

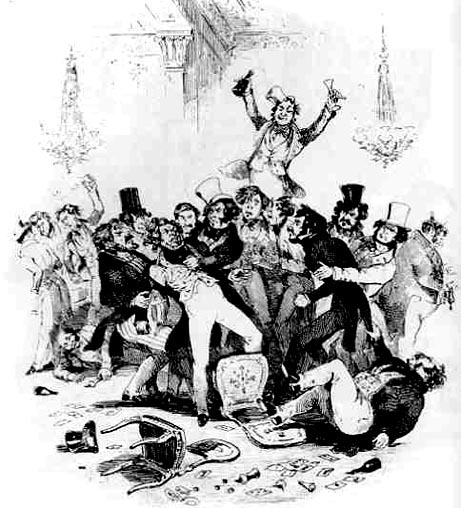

Left: Phiz introduces the chapter that sees Verisopht's death with a less distinguished scene involving The Hawk: The Last Brawl between Sir Mulbery and His Pupil (July 1839). Centre: Fred Barnard's full-page illustration of Verisopht laid out on the field of honour: All the light and life of day came on; and amidst it all, and pressing down the grass whose every blade bore twenty tiny lives, lay the dead man, with his stark and rigid face turned upwards to the sky. (1875). Right: Harry Furniss's 1910 lithograph of the same scene with violent undertones: Lord Frederick Verisopht falls in a Duel in the Charles Dickens Library Edition.

Related material by other illustrators (1838 through 1910)

- Nineteenth-Century Britain, a Nation of Debtors

- Convicted Debtors in Charles Dickens's Life and Work

- Nicholas Nickleby (homepage)

- Phiz's 38 monthly illustrations for the novel, April 1838-October 1839.

- Cover for monthly parts

- Charles Dickens by Daniel Maclise, engraved by Finden

- "Hush!" said Nicholas, laying his hand upon his shoulder. (Vol. 1, 1861)

- The Rehearsal (Vol. 2, 1861)

- "My son, sir, little Wackford. What do you think of him, sir?" (Vol. 3, 1861)

- Newman had caught up by the nozzle an old pair of bellows . . . (Vol. 4, 1861).

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s 18 Illustrations for the Diamond Edition (1867)

- Fred Barnard's 59 Illustrations for the British Household Edition (1875)

- Harry Furniss's 29 illustrations for Nicholas Nickleby in the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

- Kyd's four Player's Cigarette Cards (1910).

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Barnard, J. "Fred" (il.). Charles Dickens's Nicholas Nickleby, with fifty-nine illustrations. The Works of Charles Dickens: The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1875. Volume 15. Rpt. 1890.

Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby. With fifty-two illustrations by C. S. Reinhart. The Household Edition. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1875. I.

_______. Nicholas Nickleby. With 39 illustrations by Hablot K. Browne ("Phiz"). London: Chapman & Hall, 1839.

_______. Nicholas Nickleby. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. IV.

__________. "Nicholas Nickleby." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, being eight hundred and sixty-six drawings by Fred Barnard et al. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1908.

Created 20 September 2021