fter he has presented his theory of Typical Beauty, Ruskin then turns to the more emotional part of his aesthetic, Vital Beauty, the beauty of living things. He begins with a word painting that contains contrasted examples of both forms of the beautiful, and this is followed by an explanation of the principles of Vital Beauty:

fter he has presented his theory of Typical Beauty, Ruskin then turns to the more emotional part of his aesthetic, Vital Beauty, the beauty of living things. He begins with a word painting that contains contrasted examples of both forms of the beautiful, and this is followed by an explanation of the principles of Vital Beauty:

I have already noticed the example of very pure and high typical beauty which is to be found in the lines and gradations of unsullied snow: if, passing to the edge of a sheet of it, upon the Lower Alps, early in May, we find, as we are nearly sure to find, two or three little round openings pierced in it, and through these emergent, a slender, pensive, fragile flower, whose small, dark purple, fringed bell hangs down and shudders over the icy cleft that it has cloven, as if partly wondering at its own recent grave, and partly dying of very fatigue after its hard-won victory; we shall be, or we ought to be, moved by a totally different impression of loveliness from that which we receive among the dead ice and the idle clouds. There is now uttered to us a call for sympathy, now offered to us an image of moral purpose and achievement, which, however unconscious or senseless the creature may indeed be that so seems to call, cannot be heard without affection, nor contemplated without worship, by any of us whose heart is rightly tuned, or whose mind is clearly and surely sighted.

Throughout the whole of the organic creation every being in a perfect state exhibits certain appearances or evidences of happiness; and is in its nature, its desires, its modes of nourishment, habitation, and death, illustrative or expressive of certain moral dispositions or principles. Now, first, in the keenness of the sympathy which we feel in the happiness, real or apparent, of all organic beings, and which, as we shall presently see, invariably prompts us, from the joy we have in it, to look upon those as most lovely which are most happy; and, secondly, in the justness of the moral sense which rightly reads the lesson they are all intended to teach . . . consists, I say, the ultimately perfect condition of that noble Theoretic faculty, whose place in the system of our nature I have already partly vindicated with respect to typical, but which can only fully be established with respect to vital beauty. (4.146-147)

To clarify the second, often puzzling, theory which Ruskin presents about the beautiful, it will be advisable to continue the contrast he has begun between Typical and Vital Beauty. If one relates both forms of beauty to Ruskin's metaphysics and religion, it will be seen that although both Typical and Vital Beauty are affected by Ruskin's religious beliefs at the time he was writing Modern Painters, Volume II, the connection between Vital Beauty and God is not as clear as Ruskin obviously believed it to be. Typical Beauty is the beauty of forms and of certain qualities of forms, which Ruskin now tentatively and now firmly asserts to be aesthetically pleasing because they represent and embody divine nature. Vital Beauty, on the other hand, is the beauty of living things, and it is concerned not with form but expression — with the expression of the happiness and energy of life, and, in a different manner, with the representation of moral truths by living things. Now, Typical Beauty, which figures forth God's being, is clearly a part of Ruskin's metaphysical system, and so also is that part of Vital Beauty produced by the presentation of moral truths. This second form of Vital Beauty is closely related to Ruskin's religious world-view, since these beautiful truths exist as part of a divinely ordained great chain of being in which each living creature plays a role as agent and as living emblem of divine intention. The first problem with this form of Vital Beauty is that such recognition of moral truth seems inconsistent with Ruskin's continual assertion of the non-rational nature of the aesthetic perception. A second problem is that the beauty of happiness, the first aspect of Vital Beauty Ruskin mentions, seems only partially at home with his other aesthetic ideas.

More problems and more clues are forthcoming if one realizes that, taken together, Typical and Vital Beauty comprise a kind of sister arts aesthetic. It has often been stated that aestheticians tend to base their ideas of beauty upon the arts with which they are most familiar. This assertion is obviously true about writers of the eighteenth century, who, believing in a visual imagination, emphasized the qualities of painting and the beauties which it presented as models for all the arts. As one might expect, this same emphasis on the visual is found in Ruskin, and, in particular, his theory of Typical Beauty draws its details, if not its ultimate explanations, from theories of beauty concerned largely with the visual, the external, the element of form. But as we have seen, Ruskin draws to a large extent on expressive ideas of poetry, and these also enter his aesthetic system. For Vital Beauty, which is based on romantic theories of poetry, is concerned with emotions, with internal reactions, and with notions of psychology and morality on which romantic poetic theory depends. The extent to which Vital Beauty has a different basis than Typical Beauty is seen in the different accounts which Ruskin provides to explain their reception in the mind. A concern with internal reactions and processes of thought is characteristic of expressive theories of art, and it is appropriate that such an interest should enter what is in essence an expressive theory of beauty. For whereas Ruskin merely states that the contemplative faculty, theoria, instinctively perceives Typical Beauty as pleasurable, he describes the mechanism by which the observer perceives both the happiness and moral significance of a living being to be beautiful. This process, act, or faculty — one cannot be sure which it is — is sympathy. To solve the problems, first, of how the mind enjoys the internal mental and emotional state of another, and, second, of how moral truth is perceived by a non-rational part of the mind, one must examine the history of the term "sympathy" and attempt to show what Ruskin believed sympathy to be.

In Modern Painters Ruskin usually defines his critical terminology with care both in order to make his argument clear to the reader and to create an impression of originality and precise reasoning. In the first volume Ruskin introduces the definitions he will use for imitation, beauty, sublimity, relation, and idea. The following volume, largely devoted to his aesthetic system, defines imagination, beauty, and theoria, and the final three volumes inform the reader of what Ruskin considers to be the correct meanings of picturesque and of landscape. Sympathy, on the other hand, is one of the few terms in Modern Painters Ruskin does not trouble to define at the outset of the discussion in which it plays a part. Many years later when he addressed Fors Clavigera to the workingmen of England, he explained that sympathy, "the imaginative understanding of the natures of others, and the power of putting ourselves in their place, is the faculty on which the virtue depends" (27.627). From the fact that Ruskin did not trouble to define the term in Modern Painters one can infer that he assumed that his readers would have been aware of the various common psychological and moral associations of this term. But because it is just these associations which are most likely to trouble anyone who now attempts to follow Ruskin's aesthetic speculations, it will be necessary to examine the history of the term and its development amid systems of moral philosophy.

During the second half of the eighteenth century and throughout most of the nineteenth, sympathy, which today signifies little more than compassion or pity, was a word of almost magical significance that described a particular mixture of emotional perception and emotional communication. According to Johnson's Dictionary (1755), sympathy is "Fellow-feeling; mutual sensibility; the quality of being affected by the affections of another." For Dr. Johnson, sympathy is, first, fellow-feeling, an emotion brought forth or called into being in some manner by another human being; secondly, it is a shared interaction of emotions by several people; and, thirdly, it is the "quality" of being emotionally stirred by another's emotions. Dr. Johnson's definition of sympathy is derived from a British school of moral philosophy which referred ethics to feeling.

For this sentimentalist or emotionalist school of ethics to have developed, it was necessary that there be changes in the traditional moral psychology that had been handed down, virtually unchanged, from ancient Greece through Rome to Europe of the Middle Ages and Renaissance. (See Ernest Tuveson, The Imagination as a Means of Grace, 42-55.) These changes were brought about by the English empiricists Thomas Hobbes and John Locke, and the sentimentalist theories of ethics attempted to answer problems which these philosophers had raised about the nature of moral action. Thomas Burnet and Anthony Cooper, Lord Shaftesbury, originators of the emotionalist school of moral philosophy, based their theories of moral behavior upon emotional reactions in attempts to replace innate ideas, whose existence Locke had denied, with another means of making man innately aware of good and evil. Since Locke had demonstrated to their satisfaction that the mind cannot possess inborn ideas of God and moral right, they attempted to find another manner in which man might make moral valuations. Extending Locke's own notion that the mind has an innate power or principle that perceives differences in color, Burnet suggested that it is by means of a similar innate power that the mind perceives differences of moral value. According to Shaftesbury, the more influential of the two writers, man's power of perceiving right and wrong resides in "his natural moral sense"(Characteristics, I, 262). an internal sense much like the senses of sight, hearing, and taste. By analogy to the "feelings" of sight and sound, the subject feelings of this moral sense were thought to be the affections or emotions. This notion of a moral sense became quite important in British ethical theory and influenced Ruskin, who accepts the existence of an innate "moral sense" that deals with emotions."A Joy for Ever"(1873) perhaps best states Ruskin's acceptance of the traditional emotionalist position: "To this fixed conception of a difference between Better and Worse, or, when carried to the extreme, between good and evil in conduct, we all, it seems to me, instinctively, and, therefore rightly, attach the term of Moral sense" (16.164).

One of the changes wrought by this school of emotionalist ethics to which Ruskin was indebted was a new concentration on the emotions in ethical speculation. Since the affections, or emotions, were thought to produce moral behavior, moral philosophy naturally became the study of the affections. For this shift of emphasis from reason to emotion to occur, it was necessary for older conceptions of emotion to change. One of the premises of Shaftesbury's ethical writings, which was ultimately of great significance in theories of art and morality, is the principle that the emotions are not only equally valuable, but in certain cases superior to the conceptions of the rational, thinking mind. The emotionalist ethics based on this premise did not develop, and probably could not have developed, until Hobbes and Locke had replaced the classical and medieval hierarchical model of the mind with one in which all the faculties were in a sense equal. For centuries moral philosophy had been founded on a psychology in which reason, lord and rightful ruler of the soul, checked the often rebellious urgings of the lower faculties, sense and will. Hobbes and Locke replaced this moral psychology, in which reason dominated the hierarchy, with a psychology in which reason was dependent upon sense-data. Locke wrote his Essay Concerning Human Understanding, as he informed his reader, in order to limit to a proper sphere the endeavors of the too ambitious human mind; and the first limitation which Locke imposed, or rather, revealed, is that the understanding can only work with ideas that enter the mind through the senses. This limitation not only denies the possibility of innate ideas, it also destroys the older descriptions of the mind as capable of the immediate apprehension of truth. Locke's restriction of the understanding and his insistence that it is dependent for its ideas on the senses shatters the older hierarchical model of the mind and consequently changes attitudes toward reason and emotion. When Shaftesbury, using Latitudinarian theories of the benevolent affections, places the burden of moral behavior on the emotions, then emotion, for the first time, becomes of greater value than reason in moral theory.

When Hobbes and Locke attacked previously conceptions of reason and the hierarchical psychology with which they were associated, these philosophers clearly did not foresee that their attempts to make men aware of the true nature and importance of reason would, paradoxically, become the basis of psychologies in which feeling was not only more important than reason but in which even the role of a Lockean conception of the understanding was disparaged. Even Shaftesbury, who derived morality from the feelings and not from reason, was very much a man of his age and would have denied the great claims which those he influenced made about the role of the emotions. The Scottish school of moral philosophers, with which Ruskin was well acquainted and from which he derived many of his ideas, was the philosophical heir of both Locke and Shaftesbury, and it is in the works of Adam Smith, Dugald Stewart, and Thomas Reid, the leaders of this school, that one can observe the development of Locke's and Shaftesbury's new attitudes toward mind and reason. In Adam Smith's Theory of the Moral Sentiments, for example, reason is presented as playing a very small role in moral action. Since Smith believes that all behavior comes within the scope of morality, he believes, in effect, that reason plays but a small role in the conduct of human life. After the great paeans to reason which one finds in the Cambridge Platonists of the seventeenth century, and after the attempts of Hobbes and Locke to clarify the all important function of reason, it is surprising to encounter the intensity with which Smith denies that reason is important in decisions about moral right:

Though reason is undoubtedly the source of the general rules of morality, and of all the moral judgments we form by means of them; it is altogether absurd and unintelligible to suppose that the first perceptions of right and wrong can be derived from reason, even in those particular cases upon the experience of which the general rules are formed. These first perceptions, as well as all other experiments upon which any general rules are founded, cannot be the object of reason, but of immediate sense and feeling. . . . If virtue, therefore, in every particular instance, necessarily pleases for its own sake, and if vice as certainly displeases the mind, it cannot be reason, but immediate sense and feeling, which, in this manner, reconciles us to the one, and alienates us from the other.[Theory of the Moral Sentiments, I, 569]

Smith's assertion that the first perceptions of moral right as well as everyday moral decisions are made by the emotions, and not by the reason, is accepted by Ruskin as one of his moral and artistic premises. According to Ruskin, the imagination is not only "dependent on acuteness of moral emotion; [but] in fact, all moral truth can only thus be apprehended" (4.287). Ruskin was familiar with Smith's moral treatise, but since the emotionalistic ethics it propounded were so widely accepted and could have been encountered anywhere from Wordsworth to Dickens, it is improbable that he derived this conception of morality from any one source. Ruskin's acceptance of this kind of ethical theory explains how, when he believed that beauty was instinctive and non-conceptual, he could find beautiful something that today we believe requires the exercise of conceptual thought processes.

Another premise of emotionalist moral theory which ultimately had great effect on Ruskin's ideas was the notion that the study of the processes of the mind, chiefly of the emotions, was the proper sphere of moral philosophy. Shaftesbury himself wrote that since all moral value depends upon the affections, the study of these affections must be the subject and method of moral philosophy: "Since it is therefore by affection merely that a creature is esteemed good or ill, natural or unnatural, our business will be to examine which are the good and natural, and which the ill and unnatural affections" (Shaftesbury, Characteristics, I, 247). Because psychology had developed as a part of moral philosophy, these fields of inquiry used the same terminology, and this terminology, as much as any other factor, was responsible for the continuing close alignment of studies of psychology and morals well into the nineteenth century. The alignment can be observed in Ruskin's use of the word "moral." Much of the time it is difficult to tell whether by moral Ruskin means ethical or whether he means psychological, and one is forced to conclude that he did not differentiate between a philosophy of mind and a philosophy of morality. (I am much indebted to Professor Geoffrey Tillotson, Birkbeck College, London, who pointed out this convergence to me during my Fulbright year, 1963-64. In essence, this section derives from his brief remark — just as the later one on typology derives from his suggestion that I my first discoveries about typology were worth pursuing.) It is not that Ruskin aligns the two subjects, but rather that for him psychology and moral philosophy had never been separated. Since the emotionalist moral philosophers with whose works Ruskin was familiar, particularly Smith, did not distinguish the study of what we today would call unconscious mental processes from the study of moral decisions, it is easy to understand how Ruskin could use the term "moral" to mean simultaneously "ethical" and "referring to all mental processes." From this point of view, then, Ruskin's statement about beauty becomes somewhat clearer: "Ideas of beauty, then, be it remembered, are the subjects of moral, but not of intellectual perception" (3.111). By this statement, I take it that Ruskin refers both to the fact that he believes aesthetic perception to be unconscious and automatic, and also to his belief that aesthetic responses are made by the same faculty which makes moral valuations.

The fact that the term "moral" referred both to the study of ethics and to the study of psychology helps explain why Ruskin could consider aesthetics to be a part of the study of morality. A lack of specialized vocabularies for philosophies of morality, psychology, and beauty encouraged the continuing close relationship between these three areas of inquiry. The implications of this association appear as early as Shaftesbury. He believed both that the sublime arouses violent emotion and that emotion is the agent of moral behavior. Since Shaftesbury did not distinguish between aesthetic and moral emotion, he assumed that the perception of the sublime is, in some manner, a moral act, and that it is good for the perceiver because it exercises his moral emotions. This same connection is made with similar results throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. James Beattie, Wordsworth, Hazlitt, Shelley, and Ruskin are a few of the many who believe that the perception of the beautiful is a moral act. Ruskin's theoretic faculty, he writes, "is concerned with the moral perception and appreciation of ideas of beauty" (4.35). Ruskin here makes the same identifications as had Shaftesbury, and it appears that he also draws the same conclusion, that aesthetic emotion is morally valuable to the perceiver. Ruskin makes the point in the first volume of Modern Painters when he states that "Ideas of beauty are among the noblest which can be presented to the human mind, invariably exalting and purifying it" (3.111).

At the time, however, when Ruskin was writing Modern Painters, the idea was current that theories of beauty should be divorced from the study of morals and made the subject of aesthetics, a separate discipline. Alexander Baumgarten, a German philosopher, had introduced the term "aesthetic" in 1735 with the suggestion that the study of beauty should be concerned merely with the adequacy of the object to perception, that is, that aesthetics should be a separate, independent concern dealing only with pleasures of perception. (See Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten, Meditationes Philosophicae de Nonnullis ad Poema Pertinentibus (1735), ed. and trans. K. Aschenbrenner and W. B. Holther (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1954). This work is cited and discussed by F. E. Sparshott, The Structure of Aesthetics Toronto and London, 1963, 4, 54.) Baumgarten's ideas were already known in England, too well known for Ruskin's pleasure, and he insists several times that calling the perception of beauty aesthetic is "degrading it to a mere operation of sense" (4.35), when it is in fact an operation of the moral faculty, theoria, and hence should be called "theoretic." Ruskin probably borrowed the name of his contemplative moral faculty, theoria, from Aristotle and formed its adjective, theoretic, so as to have a counterterm that he could oppose to Baumgarten's "aesthetic" which would permit him to relate beauty to a faculty concerned both with the beautiful and the good. He was impelled to defend the importance of beauty with such high moral seriousness because he had accepted the identification, made by the emotionalist school of ethics, of aesthetic and moral emotion, and because he had accepted the general views of emotion subscribed to by this school of moralists.

Now that we have looked at the conceptions of psychology which were associated with sympathy and which permitted its development as a term of moral philosophy, we can continue with the history of the term "sympathy." Shaftesbury, who conceives of sympathy as fellow-feeling, mentions it as one of several sources of the benevolent affections which are, in turn, the source of moral action. He believes that these natural moral affections are primarily social and must be developed within a social context. (Recently in "Shaftesbury's Horses of Instruction, J. B. Broadbent succinctly described Shaftesbury's ethics as the aesthetic of an aristocracy, a morality to make men comfortable in the club of Augustan society" [The English Mind: Studies in the English Moralists presented to Basil Willey, eds. Hugh Sykes Davies and George Watson (Cambridge, Eng., 1964], 80). Edmund Burke, who wrote almost five decades after Shaftesbury, also considers sympathy primarily as one of the "social passions"(On the Sublime, 43). which harmoniously bind men together in civilized society, but for Burke sympathy is far more than fellow-feeling. It is rather an entire process of emotional identification and perception. In On the Sublime (1757) Burke explains that sympathy is the means by which we enter into the interests of other men and are forced to be moved by their actions and emotional reactions: "For sympathy must be considered as a sort of substitution, by which we are put into the place of another man, and affected in many respects as he is affected" (44). Whereas for Shaftesbury sympathy is the shared social affection of social equals, for Burke, whose conception is more typical of later authors, sympathy is an almost mystical communion by means of which the observer places himself in the emotional point of view of another person.

Shaftesbury's notion of sympathy is that it is one of the means by which the moral affections are aroused, and although he mentions a "natural moral sense"(I, 262.), he does not connect the two, and neither does Francis Hutcheson, another moral philosopher who centered his moral theory upon this idea of an internal moral sense.According to him,

We are not to imagine, that this moral Sense, more than other Senses, supposes any innate Ideas, Knowledge, or practical Proposition: We mean by it only a Determination of our Minds to receive amiable or disagreeable Ideas of Actions, when they occur to our Observation, antecedent to any Opinions of Advantage or Loss to redound to our selves from them; even as we are pleas'd with a regular Form, or an harmonious Composition, without having any Knowledge of Mathematicks, or seeing any Advantage in that Form, or Composition, different from the immediate Pleasure" (Hutcheson, An Inquiry into our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue, 135).

It was not until Adam Smith, following Douglas Hume, identified sympathy with the internal moral sense that it became the center of ethical theory (See Walter Jackson Bate, "The Sympathetic Imagination in Eighteenth-Century English Criticism," ELH, XII (1945), 146-147). In his Theory of the Moral Sentiments, Smith, much in the manner of Burke, describes sympathy as a means of entering another person's emotions, and he explains that the imagination carries man beyond the limitations of his senses, thus creating what Burke had called a "substitution." It is interesting to observe the manner in which Smith, a philosopher consciously working in the tradition of Locke, assumes that imagination can effect a mystical identification or communion with other human beings. The sympathy evoked by this process of imaginative identification is the means by which the morality of all acts is perceived. For we approve or disapprove the conduct of another person when, placing ourselves in his stead, we either can or cannot sympathize with his motives; and similarly we approve or disapprove our own actions, "according as we feel that, when we place ourselves in the situation of another man, and view, as it were with his own eyes and from his station, we either can or cannot enter into and sympathize with the sentiments and motives which influenced it" (Theory of the Moral Sentiments, I, 188-189). Sympathy, then, is in a sense a psychological explanation of the golden rule: one acts as he would be acted upon, both because one can perceive how it feels to be acted upon, and because one can perceive the other person's judgment of one's own motives. Furthermore, since the one who is acting can, by means of sympathetic perception, be the other person for a few brief moments, he is, in a sense, acting upon himself.

This conception of moral sympathy allows us to see how vital beauty conforms to Ruskin's general statements concerning the beautiful. First of all, the notion of disinterested pleasure is at the center of Ruskin's aesthetic theory, and depending on whether he is writing about beauty as emotion or beauty as quality which produces this emotion, Ruskin considers beauty to be either a feeling of disinterested pleasure or a quality which produces this feeling of disinterested pleasure. Now, since sympathy is a means of partaking of the feelings of another, and since happiness is a feeling of pleasure or some combination of pleasures, the necessarily disinterested pleasure that is produced by sympathizing must, according to Ruskin's system, therefore be beautiful. Thus, the vital beauty of happiness is simply the pleasure of another which the observer disinterestedly enjoys by means of sympathetic perception — that is, by entering for an instant into that person's feelings and making that person's pleasure his own to the extent that it can be enjoyed.

Although the history of moral sympathy clarifies to an extent what Ruskin means by the beauty of human happiness, his remarks on the Vital Beauty of plants and animals remain difficult to understand. For since happiness implies a form of consciousness rarely accorded to dogs and never to delphiniums, it seems confusing to apply the notion of happiness to animals, and even meaningless to mention it in relation to plants. Ruskin was well aware of the difficulties in his theory of Vital Beauty, and he began his discussion of it at this, its most difficult part, with an examination of happiness in organisms in which "it is doubtful, or only seeming" (4.150). He seems quite undecided as to the true nature of happiness in plants, for while he is attracted to the idea that all living things have some form of soul, a basic conservatism prevents him from definitely and finally stating that this is so. But this does not help his theory much, for if plants can't be happy, then their Vital Beauty would seem to be based, at least in part, on illusory appearance. Ruskin suggests that the truly perceptive observer may in fact perceive happiness in the mountain gentian, his first example, but then he also suggests that the percipient associates this idea of happiness with the plant because it appears to be healthy and strong. Ruskin's lack of decision is evident in his statement, that after one has discounted the effects of Typical Beauty, "the pleasure afforded by every organic form is in proportion to its appearance of healthy vital energy. . . . The amount of pleasure we receive is in exact proportion to the appearance of vigour and sensibility in the plant" (4.151). The central term would here seem to be "appearance," for Ruskin seems willing to settle for a mere appearance of sensibility. He had earlier tried to deny that association, a subjective element, had a role in the beautiful, but when he permits an illusory appearance to be a partial basis of Vital Beauty, it seems that he has now allowed association to play a most important part in his aesthetic theory. The one thing of which the reader can be certain is that happiness for plants is chiefly to be seen in the appearance (true not illusory) of life and health. And since man, a higher being, has the added dimensions of mind and spirit, it would seem that human Vital Beauty based on the appearance of life and health must be derived, in part, from the appearance of mental and spiritual health and vitality.

Two passages in the second volume of Modern Painters furnish an idea of what Ruskin meant by happiness, and hence by the Vital Beauty of happiness. First, there is the preface to the 1883 edition in which he explains that his own conception of happiness is derived from Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics. After translating a passage which in the earlier editions had appeared in the original Greek, Ruskin continues with his own remarks on happiness: "'And perfect happiness is some sort of energy of Contemplation, for all the life of the gods is (therein) glad; and that of men, glad in the degree in which some likeness to the gods in this energy belongs to them. For none other of living creatures (but men only) can be happy, since in no way can they have any part in Contemplation.' This, as I have said [writes Ruskin], goes far beyond my own statement; for I call any creature 'happy' that can love, or that can exult in its sense of life: and I hold the kinds of happiness common to children and lambs . . . no less god-like than the most refined raptures of contemplation attained to by philosophers" (4.7). The passage makes it clear that although Ruskin does not restrict happiness to the Aristotelian idea of contemplative pleasure, he still envisages it as requiring some form of consciousness: the happy being (whom we find beautiful) is able, he tells us, to love and to exult in its own sense of life, and both loving and exultation are activities which would require consciousness in some form. Although it is possible and even probable that Ruskin believed that animals have such a consciousness, it seems unlikely that he believed that plants could be aware of and exult in their own vitality. So the problem is not solved.

A second piece of evidence, however, casts more light on the problem of what Ruskin meant by happiness. When, near the beginning of the second volume of Modern Painters, Ruskin introduces his theory of Vital Beauty, he states that it is "the appearance of felicitous fulfilment of function in living things, more especially of the joyful and right exertion of perfect life in man" (4.64). This connection of happiness and function is reminiscent of the Nicomachean Ethics, and the manner in which Ruskin introduces the idea of function makes it clear that he is following Aristotle's procedure. At the beginning of Modern Painters, Volume II, where Ruskin demonstrates the importance of the theoretic faculty, he proposes to determine, first, what is useful and hence important to man:

[Anything is useful to another thing] which enables it rightly and fully to perform the functions appointed to it by its Creator. Therefore, that we may determine what is chiefly useful to man, it is necessary first to determine the use of Man himself.

Man's use and function (and let him who will not grant me this follow me no farther . . .) are, to be the witness of the glory of God, and to advance that glory by his reasonable obedience and resultant happiness. (4.28-99)

According to Ruskin, then, it is the function of man to glorify God and by his obedience (obedience it is presumed to moral law) to achieve happiness. This passage apparently refracts Aristotle's definition of happiness through Ruskin's religious belief. In the Ethics, after Aristotle has informed the reader that happiness is something final and self-sufficient, he admits that to say that happiness is the greatest good seems merely to be a platitude, and that a more definite idea being necessary, "This might perhaps be given, if we could first ascertain the function of man" (Basic Works, 942). Aristotle first excludes the life of nutrition and growth common to all living things, and he next excludes the life of perception, i.e., mere physical pleasure, common to men and animals. "There remains, then, an active life of the element that has a rational principle. . . . Now if the function of man is an activity of soul which follows or implies a rational principle [which is what Aristotle concludes] . . . human good turns out to be activity of soul in accordance with virtue"(942-943). Man's function, according to Aristotle, is virtuous activity, and this virtuous activity produces happiness. Man's function, according to Ruskin, is man's obedience to God's law, which is consequently virtuous activity and hence productive of happiness; and, according to Ruskin, by being happy man is beautiful. In his attempt to extend the conception of happiness to all living things, Ruskin has simply followed Aristotle's chain of reasoning backward, so to speak, allowing those things to be happy (animals and plants) which the philosopher had excluded. Since lesser animals can only partake of lesser, non-spiritual kinds of activity, their "happiness" is merely in vitality and health. Although Ruskin's sources thus help to explain how he came to formulate his notion of happiness, they do not dispel the apparently intentional ambiguities in his theory of Vital Beauty. I can only propose that Ruskin, here formulating an emotionalistic aesthetic, was willing to admit a subjective element to his system — although he was earlier unable to admit that beauty itself was subjective. Hence Ruskin's indecision and his multiple explanations for the perception of Vital Beauty.

Because Ruskin bases his theory of Vital Beauty on an extended conception of human happiness, one might expect that his chapter "Of Vital Beauty in Man" would have concentrated on the forms and qualities of a beauty more complete than any found in the animals of the field or in the oak and mountain flower; but, in fact, although he briefly mentions the effects of happiness on the human face and form, he devotes the larger part of his chapter to those things, evil passions of sensuality, pride, fear, and ferocity, which destroy the beautiful in man. When he formulated his aesthetic theories, Ruskin was still a devout, rather puritanical Evangelical Anglican; and, more troubled by man's fallen state than pleased by man's beauties, he begins his chapter on human beauty with a reminder of the loss of Eden, showing next how the "present operation of the Adamite curse" (4.184) shatters the image of the beautiful which should, and which in some small degree still does, dwell in the features of men. The entire chapter is marked by theological assertions which later embarrassed Ruskin, so much so that when in 1883 he added notes to Modern Painters, 37 years after the publication of the second volume, he felt obliged both to apologize for his earlier belief and to assure the reader that it was not necessary for him to "believe the literal story of the Fall, but only that, in some way, 'Sin entered into the world, and Death by Sin'" (4.184n). There is evil in man's nature; and man dies. These assertions, acceptable to the reader without reference to particular religious belief, are far different from Ruskin's earlier attempts to paint the darkened image of a sin-ridden creature whose potential beauty can never be even partially realized this side of paradise.

Ruskin's puritanical attitudes and his penchant for theological speculation shaped his early aesthetic theory to such an extent that, without reference to his religion, it would be as difficult to understand his ideas of beauty as it would be to understand the reason for the sermonizing tone with which he presents them. The emotional tone, the intellectual attitudes, and the very articles of belief which form Ruskin's religion permeate this second volume of Modern Painters, entering all aspects of his aesthetic theory, sometimes as source and sometimes as support for his ideas of beauty. Typical Beauty, for example, has its obvious inspiration in Ruskin's theology — so much so that in a final analysis his theory of Typical Beauty is best seen, not as an aesthetic theory related to his religious belief, but rather as a natural extension of this religious belief into the realm of aesthetics. The theory of Vital Beauty, in contrast, does not have as its basis any single theological principle, such as the figuring of divine nature in earthly objects; but here also Ruskin's faith plays a very important part. Although a religious theory of happiness is one major principle of Vital Beauty, in most parts of this aesthetic theory his belief does not so much shape or originate as merely support non-religious descriptions and explanations of the beautiful.

Ruskin's religion, for example, supports an aspect of his philosophy of beauty when he derives the characteristic romantic demand for particularity and detail in art from his own belief in man's fallen state. The fall of man, according to Ruskin, caused an "evil diversity" (4.176) in mankind, so that, unlike other living things, there is no ideal state or central form of human beauty. He concludes from this lack of a single ideal of human beauty, that ideal beauty, such as exists in men, is attainable only in portraiture, and that neoclassical theories of generalization, such as those of Reynolds, are inapplicable.

Another characteristic Ruskinian fusion of religion and romanticism leads to his proposition that facial expression is the chief source of human beauty. Because his puritanical attitudes toward the human body prevent his enjoying the nude in art, Ruskin has to replace classical and Renaissance conceptions of human beauty with one which does not emphasize the body. He dislikes the portrayal of the human form in art, because he believes, at this point in his career, that the body and its pleasures were necessarily suspect because necessarily corrupting. Ruskin therefore finds sensuality distasteful, and sexuality disgusting — with the result that the nude, particularly the female nude, is considered always a potentially dangerous subject for the artist to attempt, since it so easily strays into that "which is luscious and foul" (4.194). Ruskin says that few moderns, if any, have been able to avoid the dangers of this subject; and in northern painting where the nude figure looks "as if accidentally undressed" (4.198), the distrust of the nude, which Ruskin believes a modern characteristic, creates additional problems, for "from the very fear and doubt with which we approach the nude, it becomes expressive of evil" (4.198). Although Ruskin believes that moderns cannot successfully paint the nude figure, he admits that the great religious painters "with Michael Angelo and most of the Venetians, form a great group, pure in sight and aim, between which and all other schools by which the nude has been treated, there is a gulf fixed" (4.196). Prior to these men the Greeks achieved a depiction of the human form ideal in its bodily health and strength; but, for Ruskin, this perfection of the human body is but a minor part of man's true beauty.

Man's true beauty, according to Ruskin, is not found in equal degree throughout the entire body but is concentrated in the features, and this beauty appears in or upon these features when they express man's spiritual and intellectual nature. Ruskin thus uses a form of the romantic notion of expression to solve the aesthetic problem created by the opposition that he believes exists between the body and spirit, between the material and immaterial. He asserts that expression is the means by which spirit and intellect inform the face, thus making it beautiful. Human Vital Beauty is, in particular, the expression of three mental operations: that of the intellect, of the intellect joined with moral emotion, and of faith. The action of intellect engenders the appearance of "energy and intensity" (4.179) — qualities which Ruskin had earlier mentioned as characterizing non-human Vital Beauty. The appearance of the intellect working conjointly with the moral emotions creates, on the other hand, a peculiarly human form of the beautiful, the "sweetness which that higher serenity (of happiness), and the dignity which that higher authority (of divine law, and not human reason), can and must stamp on the features" (4.181). The operation of faith leaves both face and body "conquered and outworn, and with signs of hard struggle and bitter pain upon it" (4.186). Here it is the human form weakened by faith that is beautiful, the signs of submission and bodily weakness that are appealing.

These conceptions of the beautiful, like the first part of Ruskin's aesthetic, embody criteria by which he evaluates individual paintings. To create images of Vital Beauty in man, for example, the painter must necessarily avoid depicting violent or debasing emotions. Ruskin, who desires something very like a classical restraint in art, believes that the "use and value of passion is not as a subject of contemplation in itself, but as it breaks up the fountains of the great deep of the human mind" (4.204). Accepting emotionalist theories of art and moral perception, he emphasizes that the painter should only depict emotion to attain a further end, such as the rendering of character. Since he places such importance on the noble emotions, he despises a sensationalistic art which portrays violent passion only to titillate its audience, and, in fact, he holds that "all passion which attains overwhelming power . . . is unfit for high art" (4.204).

In addition to avoiding violent emotion, the artist who would create images of human beauty must beware presenting the appearance of pride, lust, fear, or cruelty which are destructive of the best in man. Ruskin's previously encountered remarks about the nude constitute his chief emphasis upon the avoidance of sensuality in art. In the course of warning against signs of pride, he singles out contemporary portraiture to which he opposes the "glorious severity of Holbein, and the mighty and simple modesty of Raffaelle, Titian, Giorgione, and Tintoret" (4.193). Lastly, "of all subjects that can be admitted to sight, the expressions of fear and ferocity are the most foul and detestable" (4.200), for these present not the healthy energy of man's body, mind, and spirit, but the disordered, debasing emotions which man received upon his fall from grace. Prohibiting all non-satirical presentation of fear, hatred, cruelty, and ferocity in art, he holds that the artist should particularly avoid scenes of war, hell, and death by violence. He thus attacks with especial fervor Nicolas Poussin's Deluge (Louvre), a "monstrous abortion . . . whose subject is pure, acute, mortal fear" (4.200), and he similarly criticizes Salvator's battle piece in the Pitti Palace "wherein the chief figure in the foreground is a man with his arm cut off at the shoulder, run through the other hand into the breast with a lance" (4.201). Furthermore, writing at a time when he still accepted Evangelical estimates of Roman Catholicism, he expresses strong distaste for both representations of hell and those "horrible images of the Passion, by which vulgar Romanism has always striven to excite the languid sympathies of its untaught flocks. . . . There has always been a morbid tendency in Romanism toward the contemplation of bodily pain, owing to the attribution of saving power to it; which, like every other moral error, has been of fatal effect in art" (4.201-202). According to Ruskin, far different subjects should appear in religious painting, for he would have it portray the highest form of Vital Beauty in man — the effects of spirit upon body.

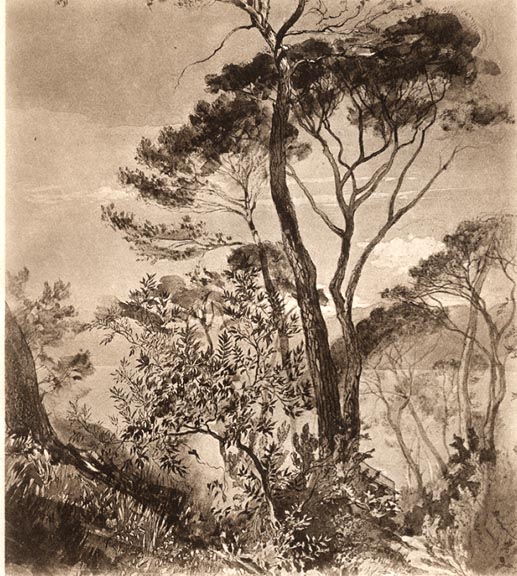

Examples of Vital Beauty from Ruskin's drawings of trees. What qualities in this watercolor

embody Ruskin's emphasis upon the viewer's empathy with living things? In other words,

what techniques of the artist can convey this effect he finds in both natures — human

nature and external nature? [Not in print edition; click on thumbnails for larger images.]

The beauty of living things, therefore, not only provides criteria for what the painter should avoid but also instructs him what to seek. In landscape, for example, it demands signs of energy, strength, and growth in trees and vegetation. Ruskin's conception of Vital Beauty thus accounts for the care with which the first and fifth volumes of Modern Painters explain the principles of tree form: only by teaching his audience to recognize signs of life in growing things can Ruskin hope to create a correct taste in landscape, an appreciation of beauty. His belief in Vital Beauty also explains his emphasis in The Seven Lamps of Architecture that beauty must depend upon natural form, for, according to him, the architect can only learn to express energy in structure and decoration by observing the power and life of natural forms. Vital Beauty also provides criteria for animal painting, requiring that the artist convey appearances, not only of physical energy and health, but also of consciousness or such intelligence as the subject may possess. Ruskin's praise of Sir Edwin Landseer's Old Shepherd's Chief Mourner in the first volume of Modern Painters reveals his attitude toward Vital Beauty in animals:

Here the exquisite execution of the glossy and crisp hair of the dog, the bright sharp touching of the green bough beside it, the clear painting of the wood of the coffin and the folds of the blanket, are language — language clear and expressive in the highest degree. But the close pressure of the dog's breast against the wood, the convulsive clinging of the paws, which has dragged the blanket off the trestle, the total powerlessness of the head laid, close and motionless, upon its folds, the fixed and tearful fall of the eye in its utter hopelessness, the rigidity of repose which remarks that there has been no motion nor change in the trance of agony since the last blow was struck on the coffin-lid . . . these are all thoughts — thoughts by which the picture is separated at once from hundreds of equal merit, as far as mere painting goes. (3.88-89)

The glossy, crisp hair of the dog indicates its physical health and vitality, but Ruskin concerns himself far more with qualities in the picture that express the animal's sorrow and loneliness. The painting, which is not as mawkish as much of the artist's later work, conveys the simple fact that the dog remains alone, its head resting on the coffin, after all others have left; and anyone who has ever seen a dog whose master has left it behind can admit that the picture, though not to modern taste, is not excessively sentimental. Ruskin, however, would take the reading farther than I have, finding human qualities, human virtues, in the animal's bearing; and at this point, most people today, except dog fanciers, would part company with the great Victorian. But whether one likes the painting or not, one must notice that the primary characteristic Ruskin admires is its ability to convey an emotion with restraint: all the signs that he interprets indicate past movements; now all is still, all is in repose.

Of far greater importance to his art criticism are the criteria which Vital Beauty provides for the painting of human beings. Ruskin's words of praise in his Academy Notes for Arthur Hughes's April Love (R. A., 1856) indicate that he believes this painter, an associate though not a member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, has succeeded in portraying feminine beauty: "Exquisite in every way; lovely in colour, most subtle in the quivering expression of the lips, and sweetness of the tender face, shaken, like a leaf by winds upon its dew, and hesitating back into peace" (14.68). Upon examining this painting (which William Morris purchased from the artist) one perceives that Ruskin is praising, once again, a restrained, quiet representation of feeling.

Left: Arthur Hughes, April Love, 1856. Right: John Everett Millais, Autumn Leaves R. A., 1856. [Not in print edition; click on picture for larger image.]

Similarly, Ruskin's praise in the Academy Notes for several of Millais's works reveals a preference for subtle depictions of quiet emotion. For example, his delight in this painter's Autumn Leaves, which he considered "the most poetical work the painter has yet conceived" (14.66), derives, one is led to believe, both from its "perfectly painted twilight" (14.67) and the lovely expressions of quiet reverie on the faces of the four girls. Again, his excessive praise of Millais's The Rescue (R. A., 1855), a painting of a fireman returning two young children to their joyful mother, was evoked both by the impassive figure of the rescuer and the noble emotion on the mother's face. Pensiveness, joy, nobility — the expression of all these, believes Ruskin, creates human beauty.

Perhaps the finest example of the kind of serene emotion Ruskin desired in art occurs in Giotto's Arena Chapel frescos in Padua. Between 1853 and 1860 he composed a series of commentaries to accompany the Arundel Society's reproductions of Giotto's paintings of the lives of Mary and Christ — the editors of the Library Edition have included the illustrations with Ruskin's text. Although he occasionally points out the artist's shortcomings, he more frequently lauds the painter's superb images of spiritual beauty. He thus praises the "submissive grace" (24.96) of the two standing apostles in the panel devoted to The Washing of the Feet; and of The Meeting at the Golden Gate (of Joachim and Anna) he writes: "The face of St. Anna, half seen, is most touching in its depth of expression; and it is very interesting to observe how Giotto has enhanced its sweetness, by giving a harder and grosser character than is usual with him to the heads of the other two principal female figures (not but that this cast of feature is found frequently in the figures of somewhat earlier art), and by the rough and weather-beaten countenance of the entering shepherd" (24.58). Ruskin finds that despite the painter's limited means, his restraint produces nobly powerful images of human beauty, and although he admits that Giotto cannot depict physical beauty very well(24.68), he believes his skill and restraint portray the more important beauties of the spirit — the admiration, hope, and love necessary to great art — better than could painters of the Renaissance. Emphasizing how much this great artist's handling of subject differs from that of later men, he comments about The Salutation:

Of majestic women bowing themselves to beautiful and meek girls, both wearing gorgeous robes in the midst of lovely scenery, or at the doors of Palladian palaces, we have enough; but I do not know any picture which seems to me to give so truthful an idea of the action with which Elizabeth and Mary must actually have met, — which gives so exactly the way in which Elizabeth would stretch her arms, and stoop and gaze into Mary's face, and the way in which Mary's hand would slip beneath Elizabeth's arms, and raise her up to kiss her. I know not any Elizabeth so full of intense love, and joy, and humbleness; hardly any Madonna in which tenderness and dignity are so quietly blended. (24.69-70)

This praise handily summarizes Ruskin's notions of the highest form of Vital Beauty in human beings, for it emphasizes the way quiet, imaginatively conceived gesture, gentle expression, and lofty theme produce the highest beauty. The emphasis upon the spiritual, which remains implicit in many of Ruskin's critiques of Giotto, appears most overtly in his praise for The Raising of Lazarus: "Later designers dwell on vulgar conditions of wonder or horror, such as they could conceive likely to attend the resuscitation of a corpse; but with Giotto the physical reanimation is the type of a spiritual one, and, though shown to be miraculous, is yet in all its deeper aspects unperturbed, and calm in awfulness" (24.88). Grasping the spiritual, and particularly the typological and symbolical, significance of Christ's miracle, this great artist presents the essential and most noble reactions to the event. In this particular panel, the painter sets his scene not in time and space but, more appropriately, in the realm of the spirit, and he thus portrays his important subject from the vantage point of eternal order, eternal peace, and eternal life. Hence in this picture of the spirit animating flesh the principle of Vital Beauty appears most clearly, for the rebirth of Lazarus is the image of the way the spirit creates beauty in fallen flesh. We here perceive the principle at the heart of Ruskin's delight in the fact that Giotto rendered admiration, tenderness, joy, dignity, and love — the noble feelings which produce noble beauty — so excellently. Here as in his theoretical writing Ruskin places emphasis upon the ascendancy of face over body, spirit over flesh, and love over all. The spirit gives life, and hence the spirit creates beauty.

In the final volume of Modern Painters (1860), after Ruskin had abandoned his early religion and much of its corollary puritanism, he expounded a new humanism that provided no place for his earlier belief that body and spirit necessarily exist in a state of conflict, or that the human body weakened and submissive is beautiful. His changed attitudes led him to dispraise medieval Christian art for the same tendency to emphasize the spiritual and to show the body outworn that he himself had earlier advocated. Writing fourteen years after Modern Painters, Volume II, Ruskin would say that man's "nature is nobly animal, nobly spiritual — coherently and irrevocably so; neither part of it may, but at its peril, expel, despise, or defy the other" (7.264). But in the earlier volume he emphasizes that human beauty depends entirely on the spiritual dimensions of man. In each of the three cases Ruskin mentions, the spirit is expressed upon the features, and it is not the human face itself which is beautiful, but only the face as symbol, as tablet upon which the mind and spirit can inscribe their images. His theory that mind and spirit create human beauty permits him to perform a tour de force, the formulation of a theory of human visible, material beauty based on that which is invisible and immaterial.

Expression is also the principle of Typical Beauty. In both Typical and Vital Beauty the physical object expresses and represents the immaterial. In both forms of the beautiful, the material object, that which is directly perceived, whether it be a human face suffused by joy and nobility or a sweep of Alpine snow glorying in unity and moderation, is a symbol through which, or on which, appear the signs of spiritual law. Vital Beauty expresses spirit, mind, and the energy of life, all informed, ultimately, by God. Typical Beauty expresses the nature of God. The twin, and in this case interchangeable, ideas of symbolization and expression grant Ruskin the means of reconciling material and immaterial, for they grant him a way of showing that the beautiful object is beautiful, as far as it is beautiful, because it is spiritual. These ideas of symbolization and expression permit Ruskin to state that beauty is, in the full sense of the word, essential, and they also allow him to defend the pleasures of aesthetic perception as moral, even religious exercises.

But the religious beliefs in which these aesthetic theories were rooted changed, and when they changed it became difficult for Ruskin to retain his theories in their original form. His loss of belief most strongly affected the theory of Typical Beauty; for after Ruskin lost his early belief, his more theological aesthetic became both intellectually untenable and emotionally uncongenial. Ruskin added a note to his chapter on Typical Beauty in 1883, many years after he had to some extent regained his faith, and in this note he informed the reader that typical now meant "any character in material things by which they convey an idea of immaterial ones" (4.76n). The central theological principle is gone, and once it had departed the theory of Typical Beauty lost all its force; for whereas one can hold that the symbolization in material things of moral qualities is beautiful, unless one can also hold that such symbolization is universal and intentional — a law of nature — beauty becomes a matter of subjective responses. It was thus that the explanation of beauty which most emphasized the objective, universal nature of aesthetic qualities became, once Ruskin lost his faith, an implicitly subjective, personal theory. Vital Beauty, on the other hand, fared somewhat better when Ruskin's beliefs changed, for based as it was on an Aristotelian notion of the happiness of function, it could easily be modified. To retain the theory of Vital Beauty Ruskin had only to return the central idea of function to its original Aristotelian acceptation and the theory could stand independently.

Ruskin's aesthetic theories are the product and the type of irreconcilable dilemmas in his thought. When he wrote the second volume of Modern Painters, he wished to take into account the subjective nature of beauty and yet make it a universal, objective phenomenon. Having begun with the premise that emotion is the basis of art, beauty, and morality, he wished to avoid the disordering, as well as the subjective, nature of emotion. And, arguing from the principle that the physical, the material, is only dross, he wished to show that the beauty of physically existing things is of greater value than the things themselves.

Last modified 6 May 2019