[Unless otherwise stated, all quotations are from the book under review, and all illustrations except the first one (the cover of the book under review) come from our own website. Captions have been added by the editors. Click on the thumbnails for larger images, sources and more information.]

As Ben Read points out in his lively Preface, the statuary of British origin in Bombay rivals that of Manchester and Glasgow combined, while Calcutta "has an array of work to match (dare one say it) London itself." Yet the existence of these works of art has been largely forgotten, not least because of the lack of any proper list or survey. This deficiency has now been remedied with the publication of this handsome volume, which catalogues nearly three hundred pieces of sculpture sent to India from England between 1798 (Lord Cornwallis by Thomas Banks) and 1938 (George V by William Macmillan). The eighty sculptors named in the index include thirty-five Royal Academicians, with Chantrey, Foley and Brock particularly well represented.

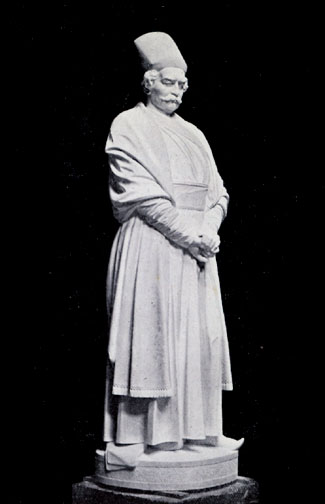

Lieutenant General Sir James Outram by John Henry Foley.

Mary Ann Steggles sets the scene with a brief history of the Honourable East India Company and its role as a patron of sculpture. She then moves on to church memorials and public statues, describing how the great and the good were chosen for commemoration, how sculptors were selected and who determined the sites and paid the bills. Finally, she tackles the question of the fate of the statues after independence in 1947. In his stimulating "View from Calcutta," Tapati Guha-Thakurta suggests that one reason why "colonial" statues had been spared desecration was because they had ceased to be objects of public interest. However, he recalls that in 1975 the eminent Indian sculptor Ramkinkar Baij had not only criticised two post-independence statues, Mahatma Gandhi and Chandra Bose, as products of official art rather than good works of sculpture, but also "unabashedly" admired Foley's Outram as "solid, strong and classical." This leads Tapati to the encouraging conclusion that colonial statuary is "metamorphosing" into a new status where it can be judged on its artistic merits, rather than on its political correctness.

Left: Charles, Marquess Cornwallis by John Bacon the Younger. Right: Curzon Monument by Hamo Thornycroft.

Against this background, the Inventory and Gazeteer provide an invaluable record of the present whereabouts of all known statues and memorials of British origin, divided into six sections: Calcutta, Madras, Bombay, Delhi, Others and Exiles & Repatriations. "Others" relates mainly to Bangalore and Lucknow, but also includes eight statues now in Pakistan. Only nine statues have actually left the subcontinent, of which two are "Exiles" (Brock's Edward VII in Canada and Weekes's Lord Auckland in New Zealand) and seven have been "repatriated" to the United Kingdom. The Inventory is followed by 200 pages of detailed description and photographs which graphically illustrate the grandeur and range of British statuary in India. Contemporary postcards and engravings show statues on their original pedestals and in pristine condition, useful when comparing the mutilated remnant of Bacon’s Cornwallis with the original monument as it appeared in the Illustrated London News of 1875, or the scattered pieces of Thornycroft's Curzon Monument with the 1911 picture from the Conway Library.

Left to right: (a) Sir Francis Chantrey's Bishop Hebert in Calcutta. (b) Thomas Woolner’s Cowasjee Jehangir in Bombay. (c) George Frampton's elderly Queen Victoria in the grounds of Kolkata's Victoria Memorial Hall, shown from the front and the back.

The Inventory reveals that a large proportion of the statues in fact remain in their pre-1947 locations. This is particularly true of works indoors, whether in churches, like Chantrey’s kneeling Bishop Heber in St Paul's Cathedral, Calcutta, or in academic institutions like the Bombay Institute of Science, where Brock’s Lord Sydenham still stands, despite Sydenham’s fear that it would end up under a heap of rubbish (quoted by Frederick Brock in his biography of his father, due to be published later in 2012). Others left untouched are Indian philanthropists like Foley’s Nusserwanji Petit and Woolner’s Cowasjee Jehangir, both in Bombay. And in Bangalore the citizens are proud of their Cubbon Park and its four historic monuments — Brock's Victoria, Jennings' Edward VII, Onslow Ford’s Maharajah of Mysore and Marochetti's equestrian Sir Mark Cubbon.

Left: Charles Sargeant Jagger's George V in Coronation Park, Delhi. Right: Sir Edgar Bertram Mackennal's Edward VII in Kolkata's Victoria Memorial Garden.

A few particularly sensitive works were moved for their own protection in 1947, like Marochetti’s Angel of the Resurrection and Brock’s Brigadier General John Nicholson, but it was not until ten years after independence that Nehru announced that government policy was to remove all British statues from public places. He added two qualifications — international ill-will should be avoided, and "offensive" statues should be moved before those of historical or artistic value. The key word was "remove" — there was to be no destruction, simply a gradual concentration of ex-British statues in designated locations, where they remain to this day. The most notable of these is Calcutta’s Victoria Memorial. Victoria is portrayed twice — Brock’s marble statue of the young queen is inside the Memorial Hall, and Frampton’s seated bronze of the elderly Empress of India is outside. The Memorial now houses some thirty five statues, busts and reliefs. Some were specially commissioned, like Mckennal’s Edward VII and George V, and others were transferred there in the 1920s, like Steell’s Lord Dalhousie. But the majority have arrived since independence, and they now form the largest single collection of British sculpture in India.

Left: The Victoria Memorial Hall, Kolkata, a handsome setting for historical artwork as well as a space for celebrating modern India. Right: The towering Durbar Memorial in the midst of what is still a graveyard of imperial statues in "Coronation Park," Delhi. At least some work is being done there now, though progress is very slow indeed.

Other concentrations of statuary are at Barrackpore, the Bhau Daji Lad Museum in Bombay, the Uttar Pradesh Museum in Lucknow and Coronation Park in Delhi. Unfortunately conditions in some of these locations are not ideal. Whereas a bronze or marble Queen Victoria, set on a well-designed pedestal, is a pleasure to behold, the sight of six such statues huddled together on the floor of an annex of Lucknow Museum is a sorrowful one. In a similar vein, Steggles writes: "Nowhere do the statues of the British look more forlorn than those relocated to the site of the Old Durbar in Delhi." Intended to be a tourist attraction, Coronation Park is now popularly known as the "Graveyard of the Statues." Jagger's George V and Lord Hardinge , and Reid Dick's Irwin and Willingdon, deserve a better fate.

However, it would be wrong to end this review on a sombre note. Steggles and Barnes have done an immense service by revealing the treasury of statues, busts and memorials sent to India in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries; abundant evidence that the talents of our finest sculptors were fully committed to those prestigious commissions. Of equal if not greater importance is the light their book sheds on the history of this artistic heritage over the past sixty five years; the confirmation that there was no "iconoclasm"; that nearly all works inside buildings such as churches, colleges and museums remain in situ; that only nine works have actually left India; and that where statues in public places have been moved, they have invariably been relocated to "sculpture parks."

By drawing attention to the fact that the conditions prevailing in some of these "parks" could be improved, Steggles and Barnes have perhaps suggested a field for fruitful collaboration in the future between conservation experts in Britain and in India. Congratulations to both authors.

Bibliography

Steggles, Mary Ann, and Richard Barnes, British Sculpture in India: New Views and Old Memories, with a Preface by Benedict Read and a View by Tapati Guha-Thakurta Kirstead, Norfolk: Frontier Publishing, 2011. 320pp. £50. ISBN 13: 978 1 872914 41 1.

Last modified 16 October 2018