This review started life as part of a longer piece, "Virtually Victorian: A return to formal engagement with the novel," in the Times Literary Supplement of 25 February 2021. It has been extended, reformatted, linked and illustrated for the Victorian Web by the author. Click on the images to enlarge them, and to find out more about them.

Matthew Sussman promotes a specialised but nonetheless widely relevant and stimulating way of attending to the literary text. The words "Stylistic Virtue" in his title refer not to morality in its most obvious sense, but to verbal properties, such as clarity and gracefulness of expression. His emphasis on such properties suggests a return to formalism; however, the moral component of "virtue" is still there, if not in the way that it was in Victorian criticism. Instead of drawing on what may be known about the author's life, work and reputation, such an approach focuses on how appropriately thoughts are organised and presented in the present context. In effect, Sussman looks for integrity in the writing itself. His primary aim is to restore perspective: to inspire "an approach to style that adequately balances the empirical rigor of 'literary linguistics' with the range of purposes encompassed by 'criticism and interpretation'" (19).

Sussman starts with a solid, scholarly history of thinking about style, one that goes back long before early twentieth-century formalism to romantic views on the organic nature of style, and then to the Aristotelian notions of style that were particularly prevalent in the nineteenth century. This was a time of crosscurrents in critical thinking, when character-based belletrism was challenged by the ideas of homegrown intellectuals like John Henry Newman and Herbert Spencer. In his The Idea of a University (1852), the former placed more emphasis on (for example) propriety, or aptness. To Newman, says Sussman, the artist was "in equal parts genius and craftsman, a worthy individual whose capacity to master the art of expression makes possible his imaginative self-embodiment through form" (39; emphasis added). Exactly contemporary with Newman's book, Spencer's essay, "Philosophy of Style," delves into the processes of the writer's mind, and is, in Sussman's words, "saturated in scientific protocols" (41). In comparison with these more incisive analyses, and their attention to technique, belletrism began to seem old-fashioned. Such ideas infiltrated academe to the extent that in 1865 the Regius Chair of Rhetoric and Belle Lettres at the University of the Edinburgh was renamed the Regius Chair of Rhetoric and English Literature instead — a telling detail.

Nevertheless, Victorian critics continued to connect style, in and of itself, with fundamental values — a tradition that survived even with the advent of aestheticism, and the idea of "art for art's sake," later in the century. Sussman finds many references to "ethical value" in Walter Pater, for instance; and Oscar Wilde too has a place here, with his claim in De Profundis that there is an "intimate and immediate connexion between the true life of Christ and the true life of the artist" (70). This recalls Sussman's earlier quotation from George P. Landow's The Aesthetic and Critical Theories of John Ruskin (1971), about Ruskin's seeing the contemplation of beauty "as a moral and religious act" (qtd. p. 52).

Thackeray unmasked at the end of Chapter 9 in Vanity Fair (p.78 in the Bradbury & Evans edition of 1848).

The tradition that somehow weathered the philosophical debates of the day was eventually submerged by the new wave of twentieth-century New Criticism and formalism. How does it help, then, to bring this notion of stylistic virtue into the equation? This is what Sussman sets out to show us in the second half of the book, as he looks in turn at Thackeray, Trollope and George Meredith. Here, close reading of well-chosen passages does more than anything else to demonstrate the value of Sussman's approach, and to present his subjects' oeuvres in a new light.

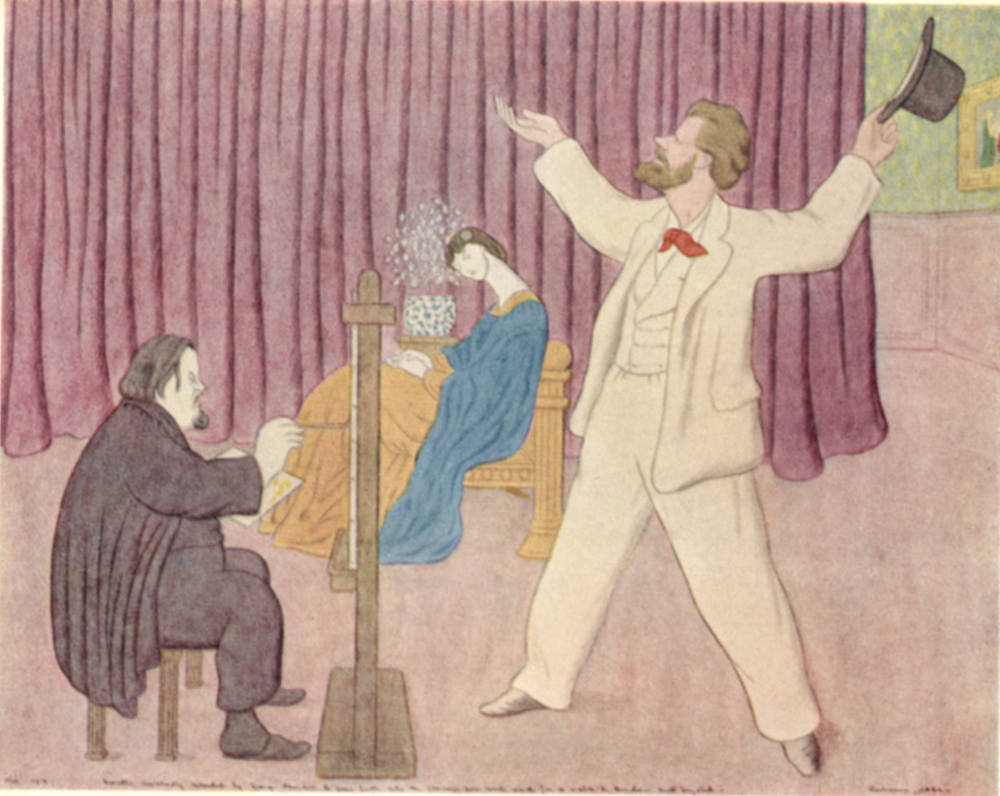

Thackeray uses asterisks to avoid going into detail about a murder in "Catherine: A Story" (Fraser's Magazine, February 1840): 202.

It is a commonplace of literary criticism, for example, that Thackeray employed a variety of styles in his early work, before exposing the worldly, the superficial and the pretentious in Vanity Fair in his own voice. Can it be left at that, though? Sussman is evidently fascinated by narratives "more postmodern in character than conservatively oriented toward the past, despite the author's preoccupation with eighteenth-century models" (97). The "stylistic pastiche" of Thackeray's first full-length novel, Catherine, comes under particular scrutiny here (112), with the perfect illustration of its "highly metafictional" procedure: the columns of asterisks substituted for the gory murder of Catherine's husband. Sussman goes on to discuss The Luck of Barry Lyndon, the next novel serially published in Fraser's, and brings in other novels as well, making it abundantly clear that Thackeray's voice, even after its apparent "crystallization" in Pendennis (212), remains versatile. This is not a matter of the author's own moral character; rather, of his highly distinctive "malleability" as a writer, and the "protean ease" with which he embraces "parody, burlesque, and bricolage." It is in this special quality of his writing that Sussman finds stylistic "grace" (97).

Analysing Trollope's style, and understanding what went into its own "ease" — this time coupled with another quality, "lucidity" — presents more of a challenge. One of Sussman's subtitles here, "It Isn't Easy Being Easy," reflects his own efforts, as he draws one subtle distinction after another, engages with numerous other critics, and endeavours to present his findings effectively. The meanings of the words "ease" and "lucidity" themselves are distinct, he argues. They refer to quite different properties of style. Here, his best guide proves to be Trollope himself, who explains in his book on Thackeray that "the easy style is simple and straightforward, having an appearance of unlabored naturalness, whereas the lucid style is precise and complete but potentially overwrought" (128). The challenge to differentiate between the two is worthwhile, since the exploration itself reveals the writer's struggles to convey his meaning apparently effortlessly and naturally, but, yes, exactly. Once again, close reading of selected passages helps to clarify Sussman's ideas, although one such passage, a description of winter light from Can You Forgive Her?, is included to show how elements of style, such as repetition and rhythm, may sometimes altogether supersede "thought content" (140). However, Sussman adds, with typical subtlety, from a purely aesthetic point of view it may sometimes "be honest to concentrate intensively and exclusively on form" (141). Fair enough. Perhaps inevitably, Sussman concludes that "Trollope's style is anything but nondescript" (143). He certainly shows how much we miss if we simply take an author's style for granted.

This is far less likely to happen in the case of Sussman's third and last example. George Meredith's style is notoriously difficult. Sliding between "curt and loose forms" (164), his writing is now highly condensed, now allusive, now digressive, now frankly impenetrable. For exactly this reason, his readership outside academe is vanishingly small. Yet other critics besides Sussman, such as Nicholas Dames in The Physiology of the Novel (2007), have also found him fascinating. Paradoxically, Meredith's style, while taxing to read at any length, is rather easy to illustrate. A wonderful passage from The Egoist, in which the heroine Clara is transported by the exquisite blossom of a wild cherry-tree, shows just how astonishing it can be. Sussman is perfectly justified in calling the description of her experience here "[e]xtrordinary" (165), and he is well able to explain why. The fact is that Meredith's style is always (to use Sussman's excellent word) "fervid." As Sussman says himself,

"Fervidness” may seem a vague criterion of style but it captures the odd way in which Meredith himself both assimilated and resisted various features of the realist landscape. On the one hand, it refers to the passion that comes from sincere belief; on the other, it alludes to energy, heat, and the possibility of over-boiling with excess enthusiasm. This is the criticism that has often been made against Meredith's style, but rather than regard it as a symptom of preciosity or decadence, we ought to see it, as Meredith did, as the natural expression of a peculiar sensibility. [165]

Indeed, in that unusual "virtue," even less detachable from the man himself than Thackeray's showman-like versatility and Trollope's assumed naturalness, lies Meredith's abiding attraction for the susceptible few.

"Rossetti insistently exhorted by George Meredith to come forth into the glorious sun and wind for a walk to Hendon and beyond," by Max Beerbohm. [Click on the image for more information.]

Perhaps this is the closest Sussman comes to the "ethos-based formalism so characteristic of Victorian criticism, which reads style as the expression of character," and was rooted "in an Aristotelian analogy between persons and texts" (72). English departments now seem to be at a crossroads, either stretching formalism to include other approaches, or incorporating it into those approaches. Either way, it can be a very fruitful mix.

Sussman's study is by no means an easy read. As suggested above, when looking at his chapter on Trollope, he himself has had to contend with the dilemma of style, even as he has analysed it in three of the foremost Victorian novelists. But as he says at the outset, "the union of 'style' and 'virtue' provides a new way of conceptualizing the ethical value of formalism, rooted not in the separation of art from life but rather in their unembarrassed contiguity" (4). Again, "contiguity" is the perfect word, especially insofar as it presumes association rather than simply closeness. Sussman leaves the reader with new insights into the authors he discusses, and, equally importantly, a new commitment to paying close attention to the style of others.

Links to Related Material

- The Aesthetic and Critical Theories of John Ruskin

- Newman and the Rhetoric of Aestheticism

- Irony in Vanity Fair

- Trollope on Style

- Description and Setting in The Shaving of Shagpat (by Meredith)

Bibliography

Sussman, Matthew. Stylistic Virtue and Victorian Fiction: Form, Ethics and the Novel. 259 pp. Cambridge University Press, 2021. £75.00. 978 1 108 83294 6

[Information about the first illustration] Thackeray, W.M. Vanity Fair: A Novel without a Hero. London: Bradbury & Evans, 1848. Internet Archive, from a copy in the University of Oxford. Web. 5 December 2023.

[Information about the second illustration] Thackeray, W.M. "Catherine: A Story." Fraser's Magazine, Vol XXI (February 1840): Last chapter, 200-12. Internet Archive. Web. 6 December 2023. [Also in Sussman 107.]

Created 5 December 2023