Tiny Tim dressed for church: headpiece for Dickens' Dream Children (1924) and second frontispiece, Tim in his Sunday best (1911, facing "Contents," page 3) — Harold Copping's twin studies of the charming boy whose social disadvantages, medical condition, and innate virtue effect the moral reformation and societal reintegration of the former miser and general curmudgeon in A Christmas Carol and subsequently Children's stories from Dickens. Line-drawing in lithograph and black-and-white lithography. Left: 4 by 2 ⅞ inches (10 x 7.6 cm), vignetted. Right: 3 ¼ by 2 ¾ inches (8.3 x 7 cm), vignetted. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

First Passage Illustrated: Portrait of a Beautiful, Doomed Child

So Martha hid herself, and in came little Bob, the father, with at least three feet of comforter, exclusive of the fringe, hanging down before him; and his threadbare clothes darned up and brushed to look seasonable; and Tiny Tim upon his shoulder. Alas for Tiny Tim, he bore a little crutch, and had his limbs supported by an iron frame! that, of all the blithe sounds he had ever heard, those were the blithest in his ears. ["Stave Three: The Second of the Three Spirits," A Christmas Carol, 71]

Second Passage Illustrated: An Exemplary "Dream Child" from Dickens

Whenever Boz comes to touch on the subject of children a tender chord seems to be struck, charged with love and affection and all the sympathies. His very heart seemed to go out to them. This was owing to his interest in the poor crippled child of his sister, Mrs. Burnett, whom he framed, as it were, in that exquisite and truly perfect crysolite, "The Christmas Carol," and where it is figured as Tiny Tim. All who heard the readings [by Dickens in the United Kingdom and America] will recall his almost broken accents, as he described it; and what a general flutter of joy there was when he officially announced that Tiny Tim did not die. [Percy Fitzgerald, "Dickens' Dream Children," introduction to Children's Stories from Dickens, 8]

Commentary: Acknowledging Tiny Tim's Iconic Status

Then up rose Mrs. Cratchit, Cratchit's wife, dressed out but poorly in a twice-turned gown, but brave in ribbons, which are cheap, and make a goodly show for sixpence; and she laid the cloth, assisted by Belinda Cratchit, second of her daughters, also brave in ribbons; while Master Peter Cratchit plunged a fork into the saucepan of potatoes, and, getting the corners of his monstrous shirt collar (Bob's private property, conferred upon his son and heir in honour of the day) into his mouth, rejoiced to find himself so gallantly attired, and yearned to show his linen in the fashionable Parks. And now two smaller Cratchits, boy and girl, came tearing in, screaming that outside the baker's they had smelt the goose, and known it for their own; and, basking in luxurious thoughts of sage and onion, these young Cratchits danced about the table, and exalted Master Peter Cratchit to the skies, while he (not proud, although his collars nearly choked him) blew the fire, until the slow potatoes, bubbling up, knocked loudly at the saucepan lid to be let out and peeled.

"What has ever got your precious father, then?" said Mrs. Cratchit. "And your brother, Tiny Tim? And Martha warn't as late last Christmas-day by half an hour!" [Stave Three, "The Second of the Three Spirits," 70]

The middle son, the cripple, is the last Cratchit child whom Dickens mentions, about one-third of the way through the narrative. Although readers today instantly recognize the iconic status of Bob Cratchit's physically challenged middle son, Tiny Tim, the boy does not appear in the initial 1843 volume, which had just a short, eight-frame narrative-pictorial program by periodical illustrator John Leech. Whereas later illustrators, beginning with the American Household Edition's E. A. Abbey (1876) accord some prominence to the child of Scrooge's clerk, Copping is the first, through two Raphael Tuck volumes, to accord Tiny Tim pride of place; in Mary Angela Dickens's retelling of the story for Children's Stories from Dickens (1924) the serious, beautiful, soulful child of financially struggling, lower-middle-class parents becomes the protagonist, and Scrooge a mere adjunct. Ironically, then, although Dickens was concerned about the plight of poor children when he wrote The Christmas Books (1843-48), Timothy Cratchit is hardly the street-boy in The Haunted Man (1848), for he is one of six much-loved children in a literate, respectable, lower-middle class family. He is not parallel in any way to "Ignorance" in Leech's Ignorance and Want. The shift in Tim's status may probably be traced back to Dickens's reading of Carol in Boston to a packed audience in 1867. Only in the ensuing Diamond Edition (1867) illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Junior, Ticknor-Fields' house artist, does Tim with his crutch appear in a frontispiece, for example. Indeed, Paul Davis notes that the Eytinge illustration of Tiny Tim and his father "was the first rendering of this iconic subject" (78).

Further Illustrations of Tiny Tim, 1868-1924

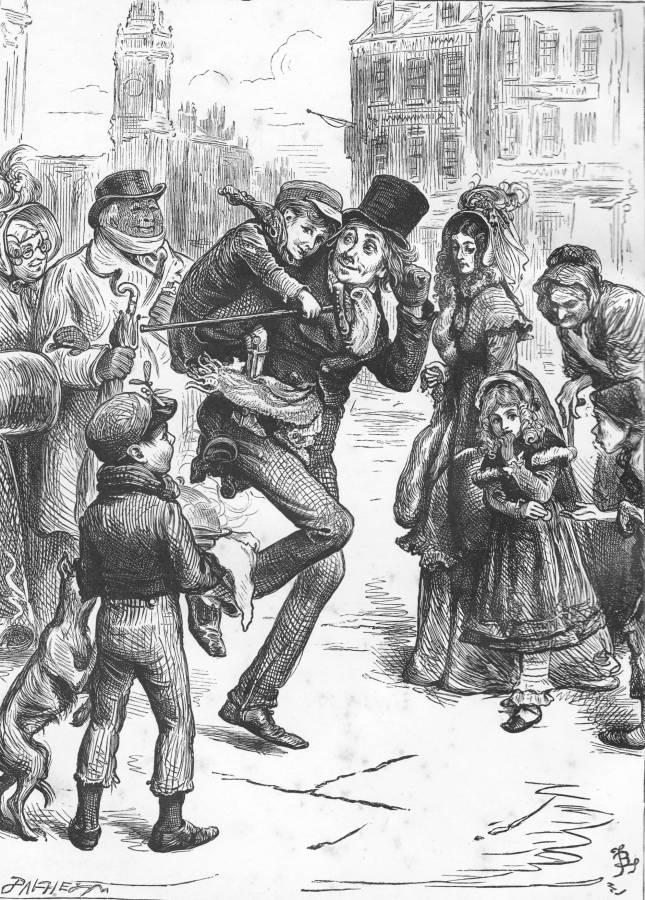

Left: Barnard's realisation of the indirect narration in which Bob and Tim return home from church through crowds of well-wishers, He had been Tim's blood-horse all the way from church, the keynote for the 1878 anthology. Right: Fred Barnard's realisation of Bob's actual homecoming, Bob Cratchit and Tiny Tim.

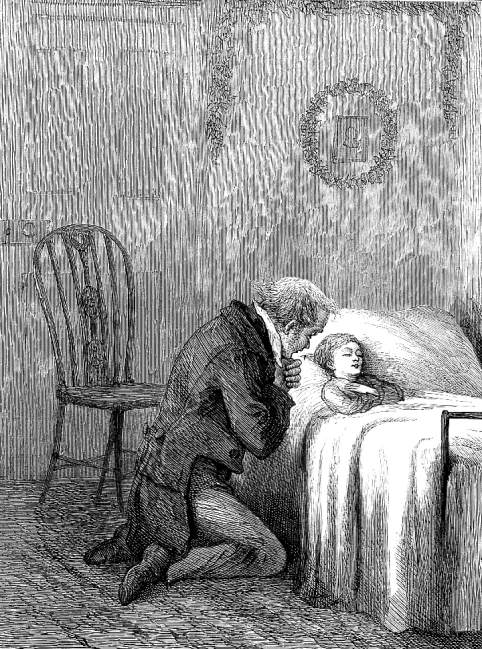

Left: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Bob Cratchit at Home (1868). Centre: Eytinge depicts Bob's praying at the child's death-bed: 'Poor Tiny Tim!' (1868). Right: Eytinge's frontispiece for the 1867 Diamond Edition of Christmas Books: Bob Cratchit and Tiny Tim. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Left: Charles Green's vignette in the 1912 Pears' Centenary Edition: Bob Cratchit and Tiny Tim: 'For he had been Tim's blood horse all the way home from church, and had come home rampant' (lithograph, 1912). Centre: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s headpiece in the Diamond Edition: Tiny Tim's Ride (1868).

Two further illustrations bear witness to Tiny Tim's iconic status; left: Charles Edmund Brock's He had been Tim's blood-horse all the way from church (1905). Right: E. A. Abbey's title-page vignette "God Bless Us Every One!" ("Stave Five," 1876). [Click on each image to enlarge it.]

Illustrations for A Christmas Carol (1843-1915)

- John Leech's original 1843 series of eight engravings for Dickens's A Christmas Carol

- Sol Eytinge, Junior's 1867-68 illustrations for two Ticknor & Fields editions for Dickens's A Christmas Carol

- E. A. Abbey's 1876 illustrations for The American Household Edition of Dickens's Christmas Books

- Fred Barnard's 1878 illustrations for The Household Edition of Dickens's Christmas Books

- Charles E. Brock's 1905 illustrations for A Christmas Carol and The Chimes

- A. A. Dixon's 1906 Collins Pocket Edition for Dickens's Christmas Books

- Harry Furniss's 1910 Charles Dickens Library Edition of Dickens's Christmas Books

- A selection of Arthur Rackham's 1915 illustrations for Dickens's A Christmas Carol

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File (Checkmark), 1998.

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being A Ghost Story for Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman & Hall, 1843.

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Harold Copping. London, Paris, New, York: Raphael Tuck, 1911.

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Charles Green, R. I. London: A & F Pears, 1912.

Dickens, Mary Angela, Percy Fitzgerald, Captain Edric Vredenburg, and Others. Illustrated by Harold Copping with eleven coloured lithographs. Children's Stories from Dickens. London: Raphael Tuck, 1893.

Dickens, Mary Angela [Charles Dickens' grand-daughter]. Dickens' Dream Children. London, Paris, New York: Raphael Tuck & Sons, Ltd., 1924.

Hearne, Michael Patrick, ed. The Annotated Christmas Carol. New York: Avenel, 1989.

Matz, B. W., and Kate Perugini; illustrated by Harold Copping. Character Sketches from Dickens. London: Raphael Tuck, 1924. Copy in the Paterson Library, Lakehead University, Thunder Bay, Ontario, Canada.

Slater, Michael. "Notes to A Christmas Carol. The Christmas Books. 2 vols. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971. Rpt. 1978. Vol. 1, pp. 257-261.

Simons, Paul, and Will Pavia. "Dreaming of a white Christmas? Put it down to Dickens's nostalgia for his lost childhood." The Times. 24 December 2008. Page 4.

Created 5 October 2023