Solitary Ebenezer Scrooge: Ebenezer Scrooge with his gruel (1924, p. 50) and The dying flame leaped up as though it cried, "I know him; Marley's Ghost!" and fell again (1911, facing p. 26) — Harold Copping's twin studies of the social isolate in A Christmas Carol and subsequently Children's stories from Dickens. Line drawing and black-and-white lithography. Left: 4 ⅞ by 3 ½ inches (12.5 x 9 cm), vignetted. Right: 6 by 4 ⅜ inches (14.8 x 11.1 cm), framed. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated from "Tiny Tim" (1924)

Well, it was Christmas eve, a very cold and foggy one, and Mr. Scrooge, having given his poor clerk unwilling permission to spend Christmas day at home, locked up his office and went home himself in a very bad temper. After having taken some gruel as he sat over a miserable fire in his dismal room, he got into bed, and had some wonderful and disagreeable dreams, to which we will leave him, whilst we see how Tiny Tim, the son of his poor clerk, spent Christmas day. [Children's Stories from Dickens, 50]

Passage Illustrated from "Stave One: Marley's Ghost" (1911)

The cellar-door flew open with a booming sound, and then he heard the noise much louder, on the floors below; then coming up the stairs; then coming straight towards his door.

“It’s humbug still!” said Scrooge. “I won’t believe it.”

His colour changed though, when, without a pause, it came on through the heavy door, and passed into the room before his eyes. Upon its coming in, the dying flame leaped up, as though it cried, “I know him; Marley’s Ghost!” and fell again. [pp. 23-24]

Commentary: Various Iterations of the 1843 Novella's Gothic Moment

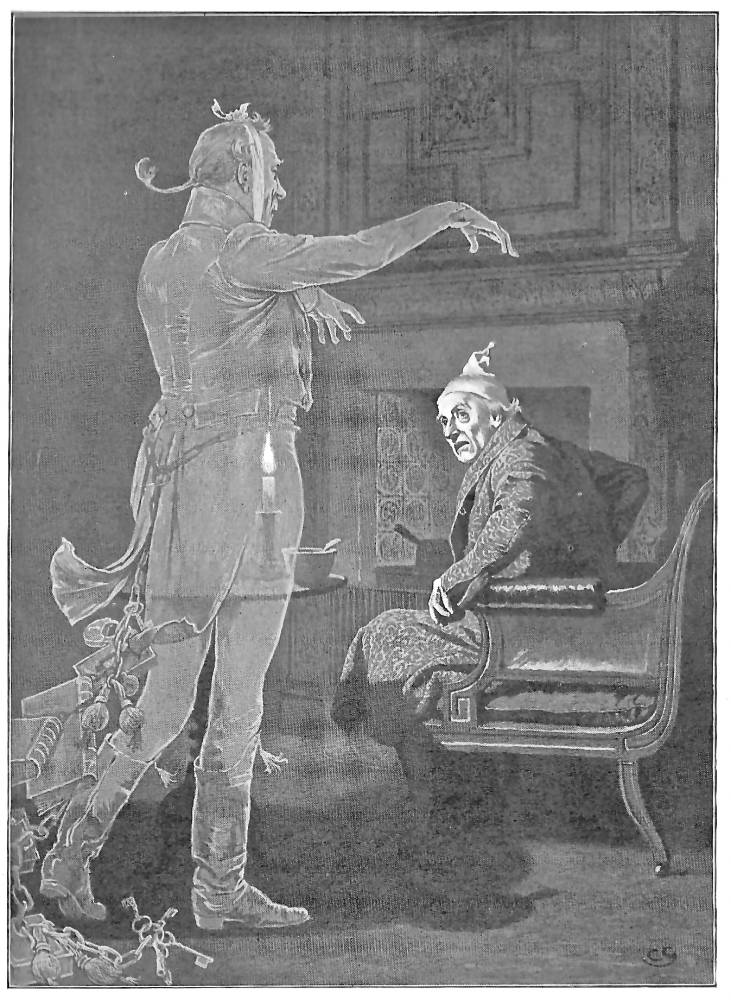

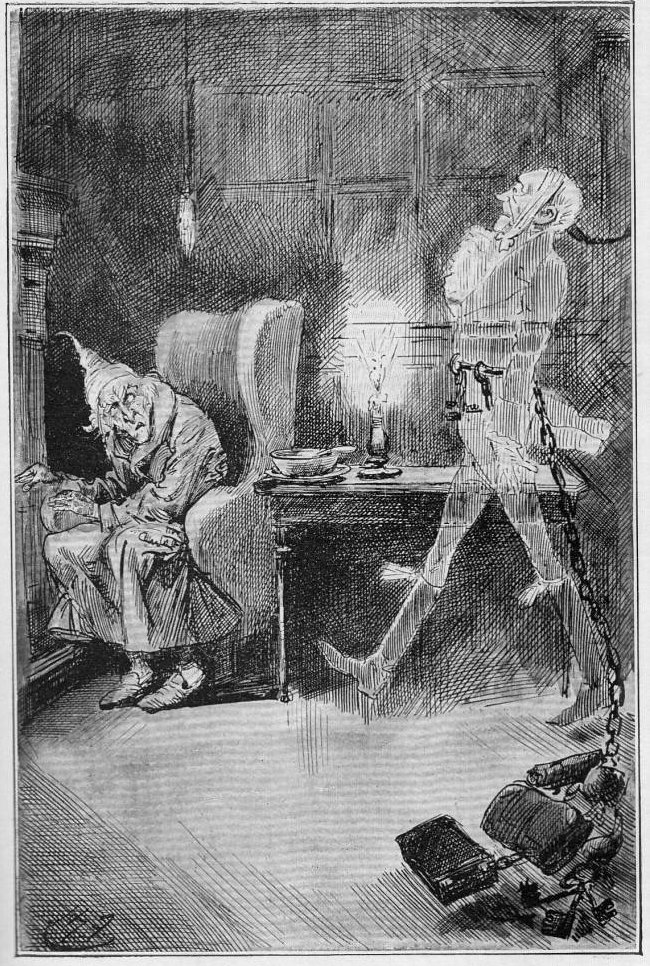

The illustrator has chosen as his subject the very moment when the chilly protagonist, in the midst of eating his gruel before bedtime, encounters the wandering spirit of his dead business partner, a whispy Jacob Marley. Copping presents the moment as Gothic rather than amusing, as in John Leech's 1843 realisation of the same instance of supernatural visitation. Copping has taken the moment seriously, depicting it with a photographic realism worthy of the new century's popular entertainment medium, the black-and-white motion picture.

In both of Copping's treatments, Scrooge in nightgown and nightcap instinctively grips the arm of his easy-chair and looks up. However, the line drawing suggests that he has just detected a peculiar noise (the sounds of Marley's chains), whereas the lithograph includes the ghostly visitor, his face and form lit by the candle beside the partially consumed bowl of gruel. The moment is made all the more mysterious by Copping's use of chiaroscuro under the side-table and behind Scrooge's chair.

Other Editions' Versions of the Solitary Scrooge as a Haunted Man (1843-1912)

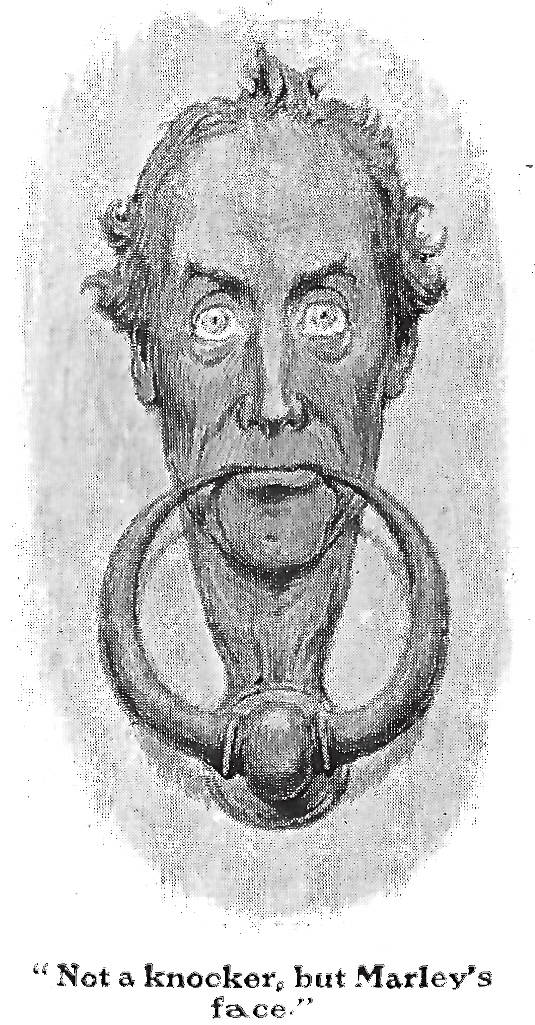

Left: Sol Eytinge, Jr., makes the fireside scene suitably Gothic in the first stave in the 1868 Diamond Edition volume of Christmas Books: Scrooge and The Ghost/span>. Centre: Charles Greene's Pears' Centenary Edition illustration of Scrooge's initial meeting with the spirit of his deceased partner for The Christmas Books (1912): Scrooge's knocker. Right: Clayton J. Clarke's John Player & Sons Cigarette Card No. 35 in the Characters from Dickens series (1910).

Left: Charles Green's cinematic version of the same scene, Marley's Ghost (1915). Centre: John Leech's caricatural interpretation of Scrooge's encounter with the shade of his partner, dead some seven years, in Marley's Ghost (1843). Centre: Harry Furniss's more whimsical version of the same scene in the Charles Dickens Library Edition, Marley's Ghost (1910).

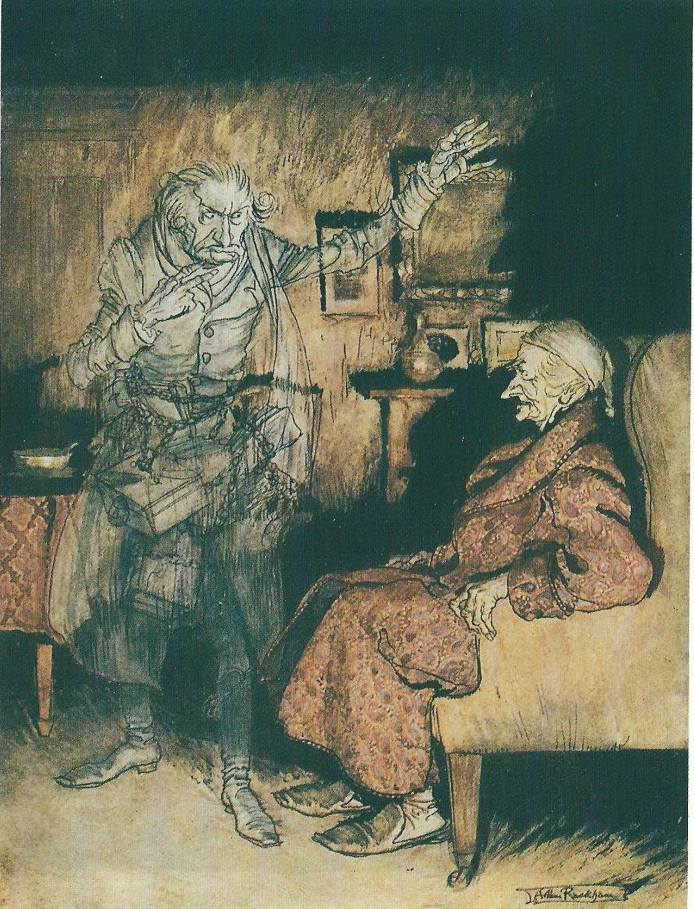

Left: C. E. Brock's portrait of a more genial Marley: Tailpiece to Stave One: Jacob Marley (1905). Centre: Barnard's Marley's Ghost (1878). Right: Rackham's "How now," said Scrooge, caustic and cold as ever, "What do you want with me?" (1915).

Above: Abbey's atmospheric "Marley's Ghost" (1876)..

Illustrations for A Christmas Carol (1843-1915)

- John Leech's original 1843 series of eight engravings for Dickens's A Christmas Carol

- Sol Eytinge, Junior's 1867-68 illustrations for two Ticknor & Fields editions for Dickens's A Christmas Carol

- E. A. Abbey's 1876 illustrations for The American Household Edition of Dickens's Christmas Books

- Fred Barnard's 1878 illustrations for The Household Edition of Dickens's Christmas Books

- Charles E. Brock's 1905 illustrations for A Christmas Carol and The Chimes

- A. A. Dixon's 1906 Collins Pocket Edition for Dickens's Christmas Books

- Harry Furniss's 1910 Charles Dickens Library Edition of Dickens's Christmas Books

- A selection of Arthur Rackham's 1915 illustrations for Dickens's A Christmas Carol

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being A Ghost Story for Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman & Hall, 1843.

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Harold Copping. London, Paris, New, York: Raphael Tuck, 1911.

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Charles Green, R. I. London: A & F Pears, 1912.

Dickens, Mary Angela, Percy Fitzgerald, Captain Edric Vredenburg, and Others. Illustrated by Harold Copping with eleven coloured lithographs. Children's Stories from Dickens. London: Raphael Tuck, 1893.

Dickens, Mary Angela [Charles Dickens' grand-daughter]. Dickens' Dream Children. London, Paris, New York: Raphael Tuck & Sons, Ltd., 1924.

Hearne, Michael Patrick, ed. The Annotated Christmas Carol. New York: Avenel, 1989.

Matz, B. W., and Kate Perugini; illustrated by Harold Copping. Character Sketches from Dickens. London: Raphael Tuck, 1924. Copy in the Paterson Library, Lakehead University, Thunder Bay, Ontario, Canada.

Slater, Michael. "Notes to A Christmas Carol. The Christmas Books. 2 vols. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971. Rpt. 1978. Vol. 1, pp. 257-261.

Simons, Paul, and Will Pavia. "Dreaming of a white Christmas? Put it down to Dickens's nostalgia for his lost childhood." The Times. 24 December 2008. Page 4.

Created 4 October 2023