These edited extracts are from Paget's own account, The Light Cavalry Brigade in the Crimea Extracts from the Letters and Journal of General Lord George Paget (John Murray, 1881). Alvin Wee of the University Scholar's Programme, created the electronic text using OmniPage Pro OCR software, and created the HTML version. Edited and added by Marjie Bloy, Ph.D., Senior Research Fellow, National University of Singapore.

2 August: ... we sailed for Varna and made the passage in sixteen hours. The harbour full of transports, at least one hundred, and more coming every day. My first visit, of course, after attending to the details of disembarkation, was to Lord Raglan, who soon sent for me to his bedroom, where he transacted his business. He looked well, though rather pale and worn. ... Everyone seems longing for an expedition anywhere, to get out of this foetid hole of cholera and disease. ... The misery of this place exceeds belief. No one allowed to move about without swords, even for bathing, for fear of the Greeks.

4 August: We completed our disembarkation today ... Working parties are busy in all directions, cutting wood for the construction of fascines and gabions. Reports of Lord Cardigan's expedition towards Silistria say that he has brought back only 80 horses out of 200.

The natives round our camp amuse themselves by shooting into our tents at night. A patrol from the Eniskillens succeeded, only two nights ago, in getting some pistols, thrown away by these scoundrels for whom we are going to fight. We are encamped on such a beautiful spot, a somewhat high sloping ridge looking over the bay.

10 August: 10 p.m. A fire is raging in the town, and spreading rapidly. The commissariat stores evidently are on fire, which will baffle all previous arrangements, and we shall starve in the meantime. The Greeks no doubt at the bottom of it; all, it is believed, in the pay of Russia. Alas, we have just buried our first man; taken ill at 8, died at 3, and buried at 7, simply wrapped in a blanket, thrown into a hole, and a field officer read the burial service.

11 August: Fire out this evening; our chief loss in biscuit, grain, and men's shoes. Five Greeks were caught setting fire to buildings by the French, who immediately bayoneted them. They do things better than we do in this way.

15 August: Dreadful accounts of the cholera everywhere (especially in Light Division)... It is sad work, as one rides about of an afternoon, meeting every thirty steps a funeral party, and seeing the rows of graves under the trees.

27 August: order just come to hold ourselves in readiness for immediate embarkation; mine the only cavalry regiment as yet ordered, but Lord Cardigan's Brigade are not yet come in. The English sick go off to Scutari.

1 September: [The] Simla steamed in this morning, and consequently all tents struck, since which our embarkation today countermanded; so we sleep with empty stomachs, and the heavens for our canopy. I must leave behind me three horses and three ponies, which I shall probably never see again.

6 September: Orders for a start were given this morning, and steam was got up, but afterwards countermanded. Valuable time lost and cholera on the increase. We are to tow two transports but have only found one of them yet. Lucan on board Simla. He has as yet got no intimation of our destination.

The Landing at Eupatoria from William Simpson's The Seat of War in the East, second series. I am grateful to John Sloan for permission to use this image from the Xenophongi web site and which graciously he has agreed to share with the Victorian Web. Copyright, of course, remains with him.

Click on the image for a larger view

13 September: 2 p.m. Just rounding into Bay of Eupatoria. Signal made: "Prepare to land troops;" so all in bustle on board. We are two miles from the shore but see no signs of soldiers or opposition, though Spitfire and Sidon are standing right into the town, apparently to summon it, as two boats are lowered, we suppose to take a flag of truce on shore, and the Simoom, with the 20th on board, is standing in with the intention of landing and occupying the town. No resistance can be made, as there is not a vestige of forts, though we see some barracks, evidently evacuated.

14 September: Off Old Fort. Weighed anchor at daybreak, and at 8.30 a.m. anchored off Old Fort (ten miles from Eupatoria), in a small bay. The French landed the first blue jackets on our right about 8.30 a.m. and planted the tricolour on the sand, our Rifles landing about an hour later. Low sandy coast, the only sign of life being a few mud cottages, a mile in shore, but lots of cattle grazing about, and had and corn (cut) without end. St. Arnaud not expected to live.

Some Tartars come in from the villages to sell us fruit and provisions.

16 September: We are at last landing our horses. Lucan and staff just landed. Surge rather increasing. Herds of cattle being driven in by those picturesque-looking fellows, the "Spahis", with their white flowing robes and veils. It is distressing to see the poor horses, as they are upset out of the boats, swimming about in all directions among the ships. They swim so peacefully, but look rather unhappy with their heads in the air and the surf driving into their poor mouths. Only one has been drowned as yet, to our knowledge. We get on but slowly with our disembarkation. The French have secured for themselves the right flank, that protected by the ships, and nearest the provisions, which gives the English the post of honour, and of hard work.

Sept. 17, Bivouac near Lake Tuzla. — Here we are at last, landed in a friendly country, the contrast between the feeling evinced to us here and in Bulgaria being remarkable. They bring us in everything and appear glad to see us. I am for the moment detached from the cavalry (for which I am truly thankful),(1) who go on to-morrow, while I have received orders to remain here, and receive my orders direct from Lord Raglan, being attached to his headquarters. He talked to me to-day in his tent; he looked flourishing. On my asking whether this unopposed landing did not indicate weakness in the enemy, he said, "Well, it would appear so; but we must wait to judge till we meet them, as perhaps they are doing this to draw us on." We are encamped on the sand between the lake and the sea, the sea almost washing into my tent. Badly off for wood, there not being the vestige of a tree; all we get is from the stranded boats, of which there are a few.

I was riding today with the Duke of Cambridge, about the French camp, when we fell in with St. Arnaud, and the contrast between him and Lord Raglan, whom we had just left, was very typical of the two nations. He had a staff of about twenty; two Chasseurs d'Afrique as advanced guard, and a sort of body-guard besides, with an orderly close to him, carrying a beautiful silk tricolour standard. We rode with him to Lord Raglan, who came out in a mufti coat to meet him, and looked as much less like a commander-in-chief as more like a gentleman.

Sept. 18. — Still here, but we march tomorrow at daybreak, our tents lying on the beach waiting to be shipped off. I have bought a pony for £2 10s., which will carry my "tente d'abri," [shelter] and give Ellis (my adjutant) the benefit of it, he being invaluable to me, and, poor fellow, very grateful for it. I have three parties out in search of carts, cattle, etc. The cavalry all marched today I said to Lucan, " I believe the best course to pursue is to obey orders, and not ask for any particular service, otherwise I should be inclined to expostulate at being the rearguard." His reply was, " You may be sure that you will come up when there is anything to do; they could never do otherwise with the most efficient cavalry regiment we have."

Sept. 20. — Yesterday we had a long fatiguing day, our march commencing (from Old Fort) at 8 a.m., having been saddled since five, and we got to the end of a fourteen miles march at 6 p.m. A fearfully hot day, without a drop of water. I never saw such a scene as the last five miles of it. An occasional shako and mess-tin lying on the ground first bore evidence that the troops in our front had begun to get fatigued and to flag.

In the innocence of our hearts we began by picking these up. A little further a man, and anon another, were found lying down, knocked up; we used our persuasive powers to make these move on, sometimes with success. This went on gradually increasing, till ere a mile or two was passed the stragglers were lying thick on the ground, and it is no exaggeration to say that the last two miles resembled a battle-field! Men and accoutrements of all sorts lying in such numbers, that it was difficult for the regiments to thread their way through them.

I was attached to no division, and therefore had no commissariat to look to. The moment came when the Rifles were ordered to a flank, and I was left friendless. In this melancholy predicament I found myself, about 6 p.m., approaching the Bulganak, where the army was bivouacking, and starvation staring me in the face, when espying at some distance what appeared to be a general officer and his staff, I made off for him, and asked an aide-de-camp who he was, who told me it was General Cathcart. Darkness had come on, and we had just finished picketing our horses, when an alarm came that we were attacked; and then came a great scramble to mount, our fellows being new to such nightwork. The alarm was a false one; but our night's troubles did not end here, for about 10 o'clock, just as the men were beginning to lie down, a staff officer from Lord Raglan came and told me that he considered we were in too exposed a position, and that we must shift our ground and close in (our bivouac was close to the village of "Sablakoi," on the Bulganak).

Turn-out No. 2 was then effected, and a pretty turn-out it was in the dark, and we had to pick our way, leading our horses for nearly a mile to the little bridge over the river, which we crossed, and then picketed our horses, and lay down in the first open space we could find, which daylight showed us was within 100 yards of Lord Raglan's head-quarters, a little white house close to the bridge. Thus we did not get settled for the night before 12 o'clock. About 3 a.m. I was woke up by the receipt of a private, note from General Estcourt, Adjutant-General of the Army, as follows:

" MY DEAR LORD GEORGE, — It is ordered that the army should get under

arms this morning in silence. There is to be no signal of trumpet or drum throughout

the army. "Believe me,

"Very truly yours,

"HY. ESTCOURT.

"Colonel Lord George Paget, 4th Light Dragoons."

This certainly looked like business.

Soon after sunrise I walked over to Lord Raglan's house, and found him standing outside talking to Estcourt and Airey. He looked, I thought, anxious. Soon after this, Lord Raglan and his staff rode close, to our bivouac, with cocked hats on, which looked still more like business.

To return for a moment to yesterday. There was some, skirmishing with the cavalry, and a man or two wounded, we hear.

The country through which we have hitherto marched consists of open plain without the vestige of a tree, partly cultivated and sometimes undulating. For the first two miles we marched rather inland, and then coasted it at that distance from the sea, the fleet all the time alongside of us. I have two troops detached, which leaves me and my major to command a squadron of 90 or 100 men. Such lovely weather, but heavy dew at night. We expect some work to-day. It is now 11 a.m., and here we have been halted for two hours, lying on the grass, two or three of us having just made a raid on a deserted sort of barn, where we got some onions.

We have in front of us gradually rising ground for some distance, which shuts out all in front from our view. We hear that we are to be opposed on a river today ; that the French and Turks are to make the first attack on the right. I shall probably be on the extreme left, and we (the cavalry) shall have to turn their right flank, that is, if I am to join the cavalry; but I get such contradictory (orders I cannot call them, but) intelligence that I don't know where or what I am.

Sept. 20. — Night bivouac on Russian position on Heights of the Alma.-- We have had a battle today! At 12 o'clock (about an hour after I had written the above) we mounted, and on coming over the crest of the hill, which I described as being in our front, there burst on our view the Russian army in position on the heights overhanging the plain in our front, at the base of which runs the River Alma, about three miles from where we first came in sight of them.

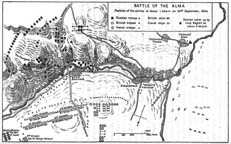

This map is taken from Christopher Hibbert's The Destruction of Lord Raglan, (Longmans, 1961) with the author's kind permission. Copyright, of course, remains with Dr Hibbert. Click on the image for a larger view

The army now had a short halt, and then advanced in order of battle across the plain. We were in a position to see the whole, as if we had taken an opera box. The Russian army in position in our front (with what appeared large masses of cavalry moving about on their right flank), and our allied armies advancing in echelon of armies from the right, and with the fleet in full view, was a fine "battle-piece." Up go the Turks and French, and about the same time out go our skirmishers, and then commences the "pop, pop." Almost simultaneously with this, volumes of smoke tell us that the village in our front is set fire to, the wind taking the smoke across our front towards the sea.

At 1.40 p.m. the action commences, and is over at 4 p.m.; to describe the grandeur of it would not be an easy task.

Our army seemed just to walk up the enemy's very strong position, and carried their entrenchments, some at the point of the bayonet. There seemed to us to be hardly a check or hesitation from the first to the last, and we could observe through our opera-glasses the actual gaps in the ranks filled up. The position on our right, that the French stormed, was more precipitous than ours, and was hardly defended by the enemy, whose chief energies seemed to be directed to their centre and right, where it was simply a long though steepish incline, without shelter.

The programme, I believe, was that when the French had got up, assisted by the shipping, they should throw forward their right shoulders, and making a sweep to their left, assist us in our more difficult task, but this, I believe, they failed to do. However, all this will come out in due time, and I shall turn to our own movements. While the action was going on, my regiment was formed up near the bank of the river, on the left. Our cavalry over the river, on our left front.

Immediately the battle commenced, I sent off Major Low to Lord Lucan (in the innocence of my heart, and goaded to do so by the officers), asking him to let us come on and join him, which, however, he declined. I then sent to General Cathcart a like message (and a very improper one, I suppose, seen by the light of after experience), with a like answer, but saying that he expected soon to hear from Lord Raglan, and then perhaps his dispositions might enable him to send us on.

When the battle was nearly over, we crossed the river, fording it, but soon found difficulty in threading our way up the hill through the numbers of dead and wounded, some lying on the ground, and others being carried to the rear, to the "Black Flag," which denoted the position of the General Hospital, formed about one and half miles from the river, on the plain. The enemy have retreated some miles, utterly licked. We ascended the hill, where the Highlanders had attacked, on the extreme left, and the hillside was strewn with the dead and dying, but nothing to the Russians on the top.

Soon after, I rode to the battery in which we had taken a gun, and found Hamilton, Grenadier Guards, who showed me the "G. G." which he had written in chalk on it. This battery was positively filled with dead bodies. The one close to which we are bivouacked was that taken by the Highlanders, but was deserted before they got up to it.

We march to the next river to-morrow, which is said to be even a stronger position than this, and where perhaps they may make another stand.

Our bivouac is next to the Guards and the Highlanders, I don't know where the cavalry are. The action took place about five or six miles from the sea; that is our left. This account of the battle may turn out to be exaggerated, but allowance must be made for a fellow who has seen the thing for the first time.

Alma Heights, Sept. 21, 7 a.m. — The poor wounded must have had a terrible night of it, bitterly cold, and we could hear their moans all night, for they are all round us. Most of our poor fellows were I hope sheltered, for they were collecting them till after dark. Oh, war, war! the details of it are horrid.

Evening. --This afternoon I have been riding all round the field (or rather hills) of battle, till I am perfectly sick.

The Russians calculated on holding the position certainly for three weeks, and the ladies from Sebastopol must have come out to see what they thought was the commencement, for numerous shawls and parasols, we hear, were found.

What a mauling they would have got had we been well supplied with cavalry! We owe, I fancy, the short duration of the battle, and the completeness of the victory, in great measure, to their proverbial fear of losing guns, which were prematurely withdrawn, to save being taken.

Alma Heights, Sept. 22. — We found little wooden crosses stuck in the ground, at various distances, denoting the range, that they might know how to fire.

I rode last evening along the valley and banks of this beautiful stream, where the wounded lay in double and treble rows, waiting for the doctors to go their rounds. Some of them complained that they had not seen one, and one said, " Oh, but we know they are all occupied elsewhere." The dead were all being collected yesterday afternoon, and the number of Russians more than was expected. My companion a great part of the time was Colonel Yea, who was picking out the wounded of his regiment, and from whom I had a very graphic account of his portion of the battle.

In my rounds I came upon Lord Raglan, just sitting down to dinner and he desired me to get off and sit down. .. he said, "Oh, George, come here and sit next to me. I have been hard at work all day, and now I should like to have a little small-talk." I then heard a great deal, as you may suppose, that was interesting, and went away with a loaf of bread, which he put into my hand. He didn't seem much satisfied with the French, and once during dinner, when he heard in the distance their endless trumpet-sounds, he said quite petulantly, "Ah, there they go with their infernal tootoo-tooing; that's the only thing they ever do." I heard all about the battle, and how St. Arnaud answered Lord Raglan when he sent to ask him to push forward his right flank, on the top of the hill, by saying that he had done his part of his work, etc. They seem to hate the French at head-quarters, and say they very nearly got our right into a mess, by not keeping in their places.

While we were at dinner, a chief of a village — prince, as he called himself — was with his followers brought to Lord Raglan, and I heard him interrogated. He said the Russians had been to his village since the battle, and told him that if he, supplied us with anything, his village would be burned down. He said that he would supply us with all he could, but that Lord Raglan must send an armed party to capture them and take him prisoner, so that it might appear compulsory. The "prince" told me his village all wished us success, but the staff-officer, Captain Hamilton, who accompanied the party to the village (seven miles off) says that he believes that he intended to throw us over, if he had had the chance.

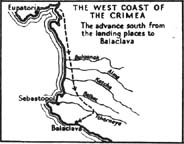

This map is taken from Christopher Hibbert's The Destruction of Lord Raglan, (Longmans, 1961), p. 10, with the author's kind permission. Copyright, of course, remains with Dr Hibbert.

Click on the image for a larger view

Our ships have telegraphed that the Russians have destroyed the bridges over the next river in our front, the Katcha, but there is still another, the Belbek, close to Sebastopol, where they may make another stand.

Lord Raglan told me that he had never been under a hotter fire, except perhaps Waterloo; and on my mentioning that I had heard that he said it was the strongest position he had ever seen, he said, "Well, I don't know that I quite said that." To look at it from the river, it appeared very strong. He told me also that the Russian generals (taken prisoners) have asked him not to let them fall into the hands of the Turks.

Bivouac on the Katcha, Sept. 23, evening. — We marched here to-day, seven miles from the heights of the Alma. About a mile from our bivouac we found a poor Russian horse standing, with a shot through his thigh. The officers shot several bullets into his head, but could not finish him, and we left him still standing, and shaking his poor head.

The people in this village say that the Russians came through here like a perfect mob that night, utterly discomfited, and acknowledging to a loss of 7000, and that they have abandoned the position on the Belbek, six miles further on, and are gone into Sebastopol.

Katcha, Sept. 24, morning. — Here we are, 10 a.m., waiting to mount, having been saddled since six; the old story, under a broiling sun, without a bit of shade. This is such a beautiful valley, prettier than the Alma, and a very strong position. The whole length of these narrow valleys are one long vineyard, and the profusion of grapes wonderful, though, alas! not ripe, from which our fellows suffer much. Cardigan has just ridden in from the cavalry (three miles off) and describes a dreadful night they had of it, having got into a narrow pass, in which he says one battalion might have annihilated them, but then he added, "Mind, Lord Lucan was in command," which accounts, in his mind, for it, and perhaps for his colouring of it. The Scots Greys have landed this morning. We are within a mile and a half of the sea, and heard cannonading, this morning, either from our ships shelling Sebastopol, or from the enemy destroying some works. The, Russian cavalry, they say, have gone off to Simpheropol. Our ride yesterday was over the everlasting "steppe," till suddenly we came on this beautiful valley, full of trees, vineyards, and villages.

Belbek, Sept. 25. — We marched about seven miles yesterday to this river, over very steep hills and valleys, very fatiguing to men and horses, often having to dismount and lead our horses. This is just such a valley as the two last, and very pretty. Burghersh just gone off to embark, with an escort of my regiment.

... yesterday the Scots Greys joined the army, having come from England after us ... The reason, we hear, why the Scots Greys have been sent on is that they want to show fresh troops (the Greys being of course especially conspicuous) that were not at the Alma, a very good reason, doubtless; but then they might ere this have relieved us by another regiment of the Light Brigade, it being the custom of the service that such a duty as that hitherto imposed on us should be taken by regiments in turn.

In the meantime, cannonading has been going on for the last three hours, at intervals. The attack on Fort Constantine is given up, and we are going round by the left, to the rear of the town, and the Engineers say it will be an easy affair. The want of precaution and tactics that the enemy has hitherto displayed is extraordinary.

Each river that we have crossed would have given them ample opportunity (even if they did not defend them) of harassing us, by destroying the bridges, wells, etc. Over this river (Belbek) the only crossing is a wooden bridge, which five men might have destroyed in as many minutes, and yet here it is intact, and all the wells in order, even to the buckets at their mouths. Our fellows were without food all yesterday, but this morning we caught a bullock, and killed him on the spot, to make sure.

I have just come in from riding with Low, a long circuit over the hills on the other (rear to us) side of the river, on our left rear, placing videttes, outposts, etc., and from which we could see for miles towards Simpheropol ; but except a couple of Cossack videttes two miles from us, we could not see a living soul. The enemy appear to be quite panic-stricken.

Black River (The Tchernaya), Sept. 27, morn. — We had a most tedious and disagreeable march yesterday, by tracks through an endless wood (in many places so narrow that horses could not go three abreast), and I believe chiefly by the compass. We had only a company of Rifles in our rear (in skirmishing, order), and did not know from one moment to another whether we should be attacked. Indeed, the following little episode will show how critical was our position considered.

About 2 p.m. we suddenly emerged on an open space of four or five acres, in the wood, nearly in the centre of which stood what had been a barrack-looking building known as "Mackenzie's Farm," the walls of which only remained, as it had been set fire to the day before, and the flames from it were still smouldering. We found our division lying down and taking their midday repose, and I was about to do the same with the 4th, when General Cathcart rode up to me and said, "If you have a mind, I will give you a little job, which may have a good effect, and which at all events will be good fun. I have, just seen Prince Napoleon, whose division is gone on, and he tells me that the road by which the Russians retreated yesterday, and which crosses our front just ahead of us, is covered with their débris, ammunition-waggons, tumbrels, etc., of all sorts, and I want you, if your people are not too much knocked up, to follow up the line of their retreat, and if you can get sight of them, to blow up their tumbrels, etc., so as to bid them a sort of defiance." I of course said we were ready, and after selecting the freshest horses, away we went, accompanied by two Engineers, for which I had bargained, and whom we mounted. It appears that Lord Raglan fell in, the day before, with the rear of a large force of Russians Making its way out of Sebastopol and bound for Simpheropol, at Mackenzie's Farm, and that our people pursued them for some distance.

Cathcart told me that the only instructions he would give me was a limit of three miles and two hours. We accordingly made the best of our way at a brisk trot, except where we were impeded by the débris of the days before, and what a scene it was! Every description of accoutrement and engine of warfare, with an occasional waggon upset, and here and there a dead horse or two, strewed along the road, which wound through a thick forest for about three miles, when we suddenly emerged on the summit of a steep zigzag descent of nearly a mile, to the vast plains below, leading to Simpheropol.

Here I halted, and was proceeding to place videttes to keep a watch, while we carried on our operations, when "ping, ping" came small friends close to our heads, and on rushing forward, we saw half-a-dozen Cossacks galloping "ventre à terre" down the winding road. This descending road we found actually blocked up with abandoned ammunition-waggons, etc., and from it we could see in the plain, three, or four miles off, a force of what appeared to be about 9000 or 10,000 of the enemy.

Here then was the very opportunity for carrying out the General's instructions. So I dismounted the Engineers, and with some of the officers accompanied them to the first half-dozen waggons we got to, not two hundred yards off, to which they quickly applied slow matches, the first of which blowing up prematurely, nearly blew our heads off also.

The limits of my time being now nearly expended, we scuttled back to the regiment, at the top of the hill, as fast as we could, and started on our way back. We, had hardly reached it when they began one by one to blow up, the effect of which (some tumbrels having small arms, I suppose, and others round shot) resembled exactly the music of a general action. This little episode repaid us well, as we thereby got a sight of the Russian force in retreat, and saw the beautiful plains through which they were marching; and I believe we saw the hills round Batchi Serai. After this the division continued its march, down a long, steep descent to the valley of the Black River, on which we are now bivouacked, the army having gone on to Balaclava. We got a view of Sebastopol yesterday on our march, from a sort of look-out or summer-house ...

I must now endeavour to explain the beautiful way in which the Russians have been out-manoeuvred in the last three days.

Menschikoff, and it is believed a large portion of his army, have escaped out of Sebastopol, and were making their way out from the south side, with the intention probably of getting round to our rear, when Lord Raglan just cut into the rear of that army during the movement at Mackenzie's Farm. Had Lord Raglan been a few hours earlier, and thus caught them in the act of ascending the precipitous road from the Black River, it would have been a desperate affair. We have by this flank movement what is called changed the base of our operations to Balaclava, which was taken yesterday, with little resistance, and which is now in possession of our fleet.

On heights before Sebastopol, Sept. 27, evening. — After a beautiful march of eight or ten miles round by Balaclava, we about 4 p.m. made the "Lights," i.e. the heights above the town on the south side. Just after crossing the bridge (The "Tractir Bridge") close to us, we found ourselves in the wake of a French division, with the staff of which is Lieutenant-Colonel Foley. I rode a great part of the way, and from them I learnt that St. Arnaud had given up the command to Canrobert. We have now, I rejoice, to say, turned the tables on the cavalry, and indeed the whole army, having left them in the plain of Balaclava well in the rear, malgré the efforts of Lord Lucan to catch hold of me.

We were threading our way through the army, in their bivouac of the night before in front of Balaclava, and we were passing the Cavalry Division, when up rushes one of Lord Lucan's staff, saying that he wished to speak to me.

I accordingly went to his tent close by, leaving my regiment on its march, and on his asking me under whose orders I was, and where I was going I replied that I was under the orders of Sir G. Cathcart, and was, by his direction, following his division. After some conversation he said, " Well, you have my orders to halt, and remain here with the Cavalry Division." I then said, "Well, my lord, I must obey such an order coming personally from you, but I hope that I shall be considered as relieved of all responsibility in the matter." He said, "I take all the responsibility on myself; dismount your men, and picket your horses."

We had not long commenced this operation when Captain Boyle (one of Sir G. Cathcart's aide-decamps) rode back to me in rather an excited state, asking me why I had disobeyed Sir George's orders, on which I took him to Lord Lucan, who then desired me to mount my regiment again and proceed after the Fourth Division.

I accordingly started off at a good round trot (for the division by this time had got a long way on), when the whole (I should think by the noise they made) of the trumpets of the brigade began a chorus of "Walk," to which (with horror do I say it) I turned a deaf ear, until one of Lord Lucan's staff came rushing after me, and asked me if I had not heard the trumpet sounds; so I changed the pace till I had got into a dip which concealed me from Lord Lucan's view, and then being urged by Boyle, riding at my side (who knew of Cathcart's annoyance at my previous halt), to get on, we trotted on again till we had reached the rear of his division, as it was ascending the hill up to the heights.(This ascent was known afterwards as the "Col de Balaclava.")

We are now in sight of Sebastopol; up here, indeed, there is a beautiful view of it. I rode up with Cathcart. As we emerged on the heights, we soon came to a stone quarry, with heaps of stone slabs squared, and the very barrows and working tools left on the around, appearing as if we had disturbed them in their work. When our men had got a little settled, I walked with him. and his staff a little more to the front, and as we lay on the ground with our telescopes out, he said, " I could get in there to-night with my division, if they would let me. I have tried hard, but am not allowed to make the attempt."

The Fourth and Third Divisions (the latter having followed the former) and my regiment are the only troops now up in the front. They soon saluted us with a shell, but it fell short.

You poor people will about this time be getting the telegraph of the Alma; how we pity you! What mischievous things these telegraphs are in time of war!

Before Sebastopol, Sept. 28, 2 p.m. — We have just come in from a sort of patrol and foraging expedition round the plateau of hills overlooking the town, taking with us all the horses we can muster each man leading two horses wherewith to load with what we could find, and poking our noses into all the deserted farmhouses and other buildings we could find, till at last we hit upon a lot of stuff like Indian grass, which we brought home, for a couple of days' consumption, for though within a short distance of the harbour no corn has as yet come up, so we are thus forced to shift for ourselves.

We wandered about all the morning, without seeing a soul, except here and there a couple of Cossacks in the distance; but in our rambles we espied a fellow quietly walking up the hill from the town, on whom Low and I laid violent hands, and sent him off to Lord Raglan. Mercy! Have we taken the first prisoner out of Sebastopol? He appeared to be a Greek, and when it is considered that he came up through all the Cossack videttes, it looks as if he was a spy. They have just set fire, to a large building outside, the town (that the savans say is a depôt of grain). This, together with the fact of the wells in the farmhouses not being destroyed, their buckets even being left, confirms the belief of how little they expected an attack from this side.

6.30 p.m. — I was interrupted by a sudden order to move off to our left and join the Third Division, and the whole army we hear was put in motion by an attack from Batchi Serai, of it is said 26,000 men, so we (England's division) have thrown our right back, our pickets being just out of gun-shot of the town. All the forage we collected yesterday we had to leave on the ground, so we are now again without any. Our horses have not had corn now for three days, and we were forced to leave three at our last bivouac to-day, utterly exhausted.

Before Sebastopol, Sept. 29, 10 a.m. — Still at single anchor with Third Division. Such a beautiful view, we can see every gun in the ships and batteries, and the people working at the entrenchments. They have been shelling us all the morning, at intervals, probably trying the range, for the shells fall far short of us.

The days are oppressively hot, and the nights equally cold.

Before Sebastopol, Sept. 30. — They have been peppering at us so all day that we have had to shift, further back. We saw them landing their ships' guns, and as they move them up, they send their balls, of course, further; but they are very innocent, and only dig into the ground, and our fellows immediately seize, upon them to grind their coffee with.

Lucan rode up to us to-day in very good humour, but I regretted to hear he had put in arrest his commissariat officer yesterday, on my reporting that I had not yet any supplies, for I believe the poor fellow did his best. He and Cardigan had a turn up yesterday, because he would not allow any troops, even the officers to have forage till the 4th and 11th (in the front) were provided for. Good man!

Those French fellows are too bad. We are ordered to move out of this to-morrow, and take ground to our right, as the French must now needs take the left, so as to be near their shipping, they having had the right and the sea up to now, so that our army have always the toughest work.

Before Sebastopol, Oct. 2. — I rode into Balaclava yesterday, and a most curious place it is; the entrance to the harbour being of that width that two ships "stem on" would reach across it; deep water, immensely high cliffs, and a sort of winding inlet, that completely hides the entrance from the sea, up all our ships, including the Agamemnon. I got on board the old Simla, lying outside, which had just brought the 4th Dragoon Guards from Varna, and after meeting with a warm welcome from all on board got some provisions which will set me up for Week.

Our divisions are now coming up to the front, and the French also. Fellows from Sebastopol get occasionally taken, and as they generally come to my tent to be forwarded under escort to headquarters, I generally fish up something from them, through my cook who is a sort of lingua franca interpreter. We sent twenty soldiers in one batch yesterday.

Oct. 3 — Another day of inaction (at least as far as we are concerned), though they are getting on with the landing of the guns, both English and French; but I don't like to go to the rear, and therefore know little of what is going on.

Oct. 5. — We are in great excitement to-day, having sent down to Balaclava to get stores from a ship, the arrival of which we heard of, and the envoy has returned with a goose, some sheep and potatoes as my share. Cardigan has given in, and gone on board ship, which leaves me topsawyer. Lord Raglan comes up to-day, and occupies a farmhouse.

I have just been dipping into one of my bullock-trunks to find something, and the contents of it will amuse you. On the top there were six or seven onions, wrapped up in a not over well-washed flannel shirt; next to which, in a very dirty old newspaper, are some mole candles, approaching; closely to the articles known as dips, loosely interspersed with these being broken bits of ration biscuit. Diving deeper, my hand arrived on half a loaf of bread, the crumbs of which will be somewhat annoying when I next put on the worsted sock in which it was packed. These with occasional lumps of sugar, pots of preserved meat, halfbroken cigars, a little more dirty linen, a ration of salt pork, and my other pair of boots (not cleaned) fill up a good portion of one trunk, and so unnerve me that I have not the courage to venture on the other, to find what of course I failed to find in the first.

Some tents have come up to us, not before they were wanted, for our fellows have suffered cruelly the last two nights from the hard rain. There is an interesting animal, called a centipede, which frequents these parts, and which the rain has kindly brought to us.

I like Evans very much to serve with, as indeed I did Cathcart (I had no time to judge of England). It is such a blessing to serve with people who are not fussy, and who are not always dissatisfied with what one does. So different from what one is accustomed to in our cavalry service, though I must say that as yet I have not had a vestige of disagreement with any General or staff-officer. I suppose that service improves people, and especially the "tyrant" Lucan, as one had always heard of him, with whom, if one ever does differ for a moment, the difference is adjusted in the most friendly and gentlemanlike way.

There is a certain portion of the programme of our daily amusements that I could easily dispense with, that of being be-capped and be-booted every morning half an hour before daybreak-mind, not sunrise, but break of day. I am now writing this to you at 5 a.m. (having been up with my horse saddled by me just one hour), and profiting by the first rays of sun from the east (I can assure you I don't feel poetical, whatever I may write) to do so. How I long for the time when I can make my servant call me at daybreak, in order to be able to tell him to go to --! But it is too cold to go on writing, and I must go and have a warm by my Hungarian cook's fire, who is preparing me a cup of hot chocolate. We live in momentary expectation of our tents being blown down, for we are encamped on a sandy soil, which makes it very dusty. There is a good deal of rock, too, which makes it difficult to drive in the tent-pegs, and when driven in they won't hold.

Oct. 7. — . We are out of hay altogether, but we, hear there is a lot of it come to Black River valley to-day, which we are to try and get hold of to-morrow.

Oct. 10. — It has been too cold to write the last two days; one can hardly hold one's pen, and it is so irksome to write with thick gloves on. We don't seem to get on, and are quite in the dark about everything. Every day we hear that on the next the attack will commence. The men encircle themselves with high stone walls (for there are plenty of stones), and light a fire in the centre but the wood is getting scarce, and will be more so. The cold is so intense that ten of our half-starved commissariat ponies died last night. About once every day and night a fellow gallops in with a report that the Russians are advancing in numbers. Douglas and I had another look round the entrenchments yesterday, but this time the French ones, which appear strong and well made. He took a fur-coat of Menschikoff's from his carriage, the day of our raid at Mackenzie's Farm, which I tell him was his cook's, but he looks very comfortable in it. They are hammering away to-day more than ever, it amounts almost to a cannonade at this moment. Prince Edward's tent is close to mine, and we see a good deal of each other. He is a good campaigner, and always makes the best of everything.

Oct. 12.-- I rode with Prince Edward to-day to Lord Raglan's, a nice house on the steppe about two miles off. Fire to open on Sunday. I afterwards went round the entrenchments with Evans and Estcourt. No joke going with those sort of folks and their staff, for one gets awfully peppered at, riding in such a body. Two or three shells came too near us to be pleasant, at which my most sensible and discriminating "Exquisite," was much frightened. We hear the cavalry are supposed to have made rather a muck of it the other morning. At daybreak a reconnaissance came round upon Balaclava, which it is said they lost an opportunity of cutting off.

We are now regularly turned out about midnight, and I shall soon wake at the regular time, but we always turn in again in half an hour. Every fool at the outposts, who fancies he hears something, has only to make a row, and there we all are, generals and all. Well, I suppose 500 false alarms are better than one surprise, so there is no help for it. I have just had a message to say we must be on the alert to-night, as if we were not so every night, nolens volens [willy-nilly].

The Russians have fired thousands of shot, and as yet have only killed four men and a bullock. We hear that Cathcart is very angry at the way things are going on, and at his never being consulted. What a thing war is, and what wrangling and jealousies does it engender!

There are Lucan and Cardigan again hard at it, because they can't agree, and it is found desirable to separate them. Cardigan must needs be ordered up here to command the 4th and 11th, both of which are usefully placed, with their respective divisional generals, and all this must needs be upset to part these two spoilt children.

The view from our heights is one grand panorama, and from here we can take, in at a glance the scene of all our late and present operations, since the passage of the Belbek. The, boldness of the scenery magnificent, with the end of the Caucasian range of hills (as we are told) overtowering Balaclava, though far off, and the ruins of Inkerman across the valley of the Black River to our right, very picturesque. But as it is said that there is but one stop between the sublime and the ridiculous, I shall stop.

Oct. 13. — We were left quiet last night, without an alarm. I had a long ride to-day with Prince Edward all round our lines, and a long talk with Cathcart who don't seem to approve of all this delay, and said that at least they might let him, as he proposed, silence some of their batteries, which are annoying our working parties, and by which we lose men daily, for he says he could easily do it, and without the heavy guns. Cardigan has pitched his tent up here, looking ill. He told me that we (4th and 11th) are to be separated from our divisions, and be brigaded under him, which Evans didn't seem to approve of, when I told him. The Earl is very gracious to me, but I always "My lord," him, though he has returned to "George Paget." However, I should have done this in any case, while out here. Cathcart seemed apprehensive of our being attacked.

Camp near Balaclava, Oct. 14, evening. — Cardigan had a turn-up with me to-day — our first and last, I hope, for I had rather the best of it. It happened in this wise.

I received a Brigade order, early in the morning, to parade (with the 11th Hussars) at 1 p.m. at a spot indicated, a mile off, for the purpose of marching under Lord Cardigan to join the cavalry division down here. Having been attached to the Second Division by an order from head-quarters, I could not of course obey the Brigade order, that is, without the knowledge and sanction of Sir De Lacy. I accordingly went to his tent, and he immediately despatched a letter to Airey informing him of what had happened, and expressing a hope that we might remain with him, at the same time he ordered me not to move till the answer came, and said that, as he was going out for some hours, he had begged that the answer should be sent under flying seal to me, and that I was to open it and act upon it.

I had, however, taken the precaution of decamping and having everything packed on the mules, and the horses even bridled, before one o'clock. That hour came, but no answer, and I saw the 11th in the distance mounted on parade, and the General and his staff; so I sent an officer to him, explaining how I was circumstanced. In an hour the answer from head-quarters came, saying that the regiment was to join the Cavalry Division, but an officer's party of twenty men were to be left with the Second Division. I accordingly trotted off, and found his lordship in a very angry state, awaiting me on parade.

On my arrival, "Officers commanding regiments" were sent for, and with a preparatory twist of his moustache he thus addressed me, "Pray, Lord George Paget, I wish to be informed why my brigade order has not been obeyed, and why I have been kept waiting for you the last hour? " etc. I quietly answered, "If your lordship will give me the opportunity of explaining the reason, I think I can satisfy you," etc. He replied, "Proceed, my lord." I then told him what I have just narrated, and then, with another twist of his moustache, he replied, " Quite satisfactory, my lord, be pleased to join your regiment."

Now talk of general actions and great victories! I pride myself on this one, I assure you.

Sir Colin Campbell is sent down to command at Balaclava, and Lucan is ordered to " render him all assistance in his power." Cardigan dines always on board his yacht, and sometimes returns here to sleep.

Portal had a narrow escape of being cut off with his regiment yesterday. He was on a patrol with twenty men, and thought he would give his thirsty horses some drink in the Black River, when he luckily caught sight of a strong party of the enemy on his flank, which made him alter his mind, and retrace his steps, through a narrow gorge by which he had come; and only just in time, for another minute or two and he would have been cut off, and he deserves great credit for the way in which he managed it.

Balaclava, Oct. 17. — Well. The ball was opened at 6.30 a.m.. to day; our morning a most exciting one, but we are so completely tied down that we daren't move. Lucan got a despatch from Airey, that all was going on satisfactorily. Russian ships got more out of reach, but the Twelve Apostles injured. The large tower on our right front silenced, and two magazines blown up, but one of our Lancasters burst. Tremendous explosions all day, and a talk of the assault tomorrow. Cardigan has not appeared to-day, so I am in command, which I suspect the Russians must have heard. We are mounted down here every morning an hour before daybreak, and sit there for two hours, till Lucan has been round the outposts, and then we turn in. Coldish work, with a thick mist, and of course quite dark.

Oct. 19. — We had such a long, day yesterday. We were attacked or rather strongly threatened. We had just turned in from our morning parade, about 9 a.m., when an orderly from the outpost told us they were coming on in force from the Tchernaya, so away we went to the front of our position (a ridge of heights occupied by Turkish batteries), and there they were, sure enough, coming over a ridge of hills, about 1500 yards off. They then took ground to the right first, and then to the left, and we opened on them, sending a few shot into the thick of them, but the brushwood prevented our seeing with what effect. However, after about four hours they retired behind the hills, and we saw no more of them except their videttes, which enabled us in turn to take our corps back to camp (only half a mile to the rear), and get the men and horses fed. We did not finally get back to camp till 8.30 p.m., sixteen hours. Cardigan appeared about 11, having been, De Burgh told me, very unwell all night. I believe really he is ill, and that this will be the end of him, but he only remained a couple of hours.

We hear that the Engineers are not satisfied with the mischief done, finding that the Russians repair as fast as their batteries are silenced; in short, that the affair hangs fire, but that Lord Raglan is satisfied. Then I must return to my old, or rather new friend, Sir Colin, who said last night, "My Lud" (he always commences thus), " people must be disappointed who expected such a place as that to fall in a few hours, and I am not surprised," etc.

Oct. 19, evening. — I went up to the front this afternoon, but one could not see much for the smoke, and I tried to suck Cathcart's brains as to what he thought; he did not speak despondingly, though nobody crows much now. Also General Goldie, and some, of the head-quarter staff, who all seemed to think the upshot of it would be "point of the bayonet," but within three days, if at all, for the ammunition won't last longer. We are encamped now in a bed of a sort of thorny nettle, and this is a correct drawing of our tent companions.

At parade to-day, the brigade major came up to me, and after waiting some time, asked me, as Lord Cardigan had not come in, to form up the brigade, time pressing, on account of the hour of the division parade, on which I gave, the necessary directions. Five minutes after up comes Lord Cardigan, saying, "Lord George Paget, why were you to assume that I was not coming to parade?" I explained to him that it was on the report of his own brigade major, on which he flew off at him very irate. But we shall never quarrel, I know that. He is easily managed, with calmness and firmness, and when one is in the right — which it is not difficult to be with him.

Oct. 21. — There, was an alarm here at 4.30 p.m. yesterday, which turned us out, and we remained "standing, to our horses" all night, turning in again at 6 this morning. This is only what the infantry have to do continually, but with them there is some reason in such a proceeding, and people never complain when they are usefully employed, however harassing the work may be, but cavalry cannot act on a very dark night (which this was), and the use of outposts, etc., are generally considered to be to give the others rest. However, the attack last night was, I believe, considered imminent. Some 7000 or 8000 of the enemy advanced about 4 a.m., and we could hear their bands playing their advance in the dark; but they soon retired again.

Twice in the night our batteries (Balaclava) and our outposts on the hills opened fire, which was a pretty sight in the dark (a peculiarly dark night). People in the dark fancy they see and hear a good deal and fire, at anything, which a defunct old cow lying in front of us testifies to. Such a night as the last is hard on the horses, and also on cavalry men, who have to supply all their own and their horses' requirements all day. Cardigan was out part of the night. Siege made, better progress yesterday, and people more in spirits about it, and more, ammunition came into Balaclava to-day.

Oct. 21, evening. — If the Russians are clever they will take care that we have no more repose, for they can easily see that we all turn out on the appearance of a few of them. Lucan gave my regiment a little address to-day, just before (as he thought) we were going down to make an attack, begging us to pull up in time, and not get out of hand. He spoke well.

Oct. 22.-- Very quiet here to-day and no alarms. Our horses beginning to suffer much.

Oct. 24 — The rain come at last. I suspect we know little of the désagréments of campaigning till we have experienced that. A good deal of chaff goes on about the inaction of the cavalry, which we only laugh at. The Russian cavalry, which is ten times as strong as ours, has never yet been made use of. We have been ready and effective if wanted, but really as yet there has been no occasion for our services, except after the Alma, when Lord Raglan would not let us go.

They are afraid that Dunkellin may have been bayoneted, and have sent in a flag of truce to find out about him. It appears to have been his own fault, or rather his blindness, for the men told him it was a Russian picket in front of him, and he would not believe them.

Oct. 25, evening. — Well, we have had a fearful day's work, out of which it has pleased God to bring me harmless.

At 6 a.m. they attacked our heights and the Turkish batteries, from which they drove those fellows Pellmell. They then, about 11 a.m., came across the plain to us, right up to Balaclava and attacked our heavy brigade, who, with us, had in the meantime retreated behind our lines. The heavy brigade charged them beautifully and routed them, on which they retired to the heights they had taken from the Turks.

Things thus remained for about an hour, when the Light Brigade advanced down a valley, in rear of the position we had lost. We rode at a fast trot for nearly two miles without support, flanked by a murderous fire from the hills on each side. Well, last we got up to their guns and cavalry, and took the former (nine, I counted), sabred some of the drivers, and, to our horror, then found that we were not supported!

Oct. 26, 1 p.m. — At 8 p.m. last night I was interrupted by a remove, farther to the rear, which prevented our getting our tents up again before 10.30 p.m. on this hard day. I therefore now resume my narrative.

Thus we were a mile and half from any support, our ranks of course broken (most, indeed, having fallen), with swarms of cavalry in front of us and round us. Such a scene it would be useless to describe.

We had got beyond their guns, at the entrance of a sort of widish gorge, when, finding it useless to proceed, our fellows turned round to go back, and about we went. At this moment, however, seeing a lot of their cavalry coming on us, within fifteen yards, I holloaed to them (the remnants of the 4th and 11th, the only two regiments then in front) to "front," which they right gallantly did, when a cry arose, "They are coming down on us in our rear, my lord;" and to our consternation we saw a regiment of Lancers (fresh disengaged ones) formed up in our rear, between us and our retreat. The case was now desperate. Of course, to retain the guns was out of the question. We went about again and had to cut away through this regiment, which had skilfully formed so as to attack us in flank (our then right flank).

I holloaed "Left shoulder forward!" but my voice was drowned, and I hesitate not to say that had that regiment behaved with common bravery not one of us would have returned. I am no swordsman, but was fortunate to disengage myself and get through them, and I had the worst of it, for in the mélée I had got on the right flank (that exposed to them), and my horse was so dead-beat that I could not keep up, and saw the rest gradually leaving me at each step. Well, having got by them, we had to ride back a mile, through the murderous fire we had come through, of guns, shells, and Minié rifles from the hills of brushwood on each side; and all I can say is, that here I am, but how any of us got back I don't know. Cardigan led the first line, 11th, 13th, and 17th; I led the second line, 4th and 8th.

Cardigan came up before, and said, "You must give me your best support." We rode on in this disposition for perhaps a third of a mile, when the 8th Hussars would gradually incline away to our right, though I continually holloaed to them to keep to us. During the advance, however, the 11th dropped in rear of the 13th, which brought the former and the 4th into action with the enemy about the same time, the 8th having gradually fallen to our rear. When I, with the 11th and 4th, got to the guns, and saw all their host advancing, I looked in vain for the first line, and could never account for them, till I came back and said, " I am afraid the 13th and 17th are annihilated, for I saw nothing of them;" when I found that the few of them remaining had returned, unobserved by me, by ones and twos, and that they had got back first; so that in fact, when we had got to the end of this horrid valley, the 11th and 4th were the last left there.

We turned out in the morning about 700 strong, and in counting losses when we got back we counted 191. Not an officer of the 4th escaped without himself or his horse being wounded. Poor Halkett, we believe, killed. He was struck down in the advance; Sparke missing, supposed to have been sabred in the mêlée at the end, and Hutton shot in both thighs and his horse wounded in eleven places; my horse was grazed in three, or four places, and I had a shot through my holster. My poor orderly was knocked over, as well as my trumpeter, both by my side. Every trumpeter in the regiment, and two serjeant-majors out of three knocked over.

Oh, how nobly the fellows behaved! At one time we were, between four fires, or rather four attacks — right and left, front and rear. That is, a heavy fire from right and left, and cavalry in front and rear; and during all this time the fellows kept cheering! The 13th suffered the most, the 4th next. Alas! alas! it was a sad business, and all without result, or rather with the result of the destruction of the Light Brigade. It will be the cause of much ill-blood and accusation, I promise you.

There is, or rather was, an officer named Captain Nolan, who writes books, and was a great man in his own estimation, and who had already been talking very loud against the cavalry, his own branch of the service, and especially Lucan. Well, he rides up to Lucan with a written order signed "R. Airey," saying the cavalry were to recapture the guns taken in the morning. Lord Lucan says, "But what guns?" on which he insultingly replied: "There is your enemy, my lord." Cardigan most gallantly led us on, arriving himself first at the guns. Nolan — the principal cause of this disaster — was the first man killed.

After this hard day (over about one o'clock) we were not allowed to go back to our lines till 5 p.m., though only 500 yards off, and none of the men or horses had had anything to eat since the night before.

The attack of the Heavy Brigade was actually in our lines, so we have lost a good deal of property, the answer about everything being, "Oh, it was knocked over in the attack — I cannot find it;" or "The Turks must have stolen it." There is no doubt that the latter did take a good many things from our tents in their retreat in the morning. I have captured such a fine black horse, with beautiful action.

Our return was really a sort of triumph, the troops cheering us as we came up, and the fellows rushing forward to shake hands with us on our escape. As for myself, I take no credit — I could not help myself; I was ordered to go on, and go I must, but that in the whole of that devoted brigade there was not one man who hesitated was a noticeable fact now that one looks back at it.

In the afternoon I rode down to the Guards (to try to get something to eat) and had to tell them a sorry tale of some of their friends, and it was a strange coincidence that two of the first officers who rushed up to me were Bradford and Mark Wood, who each had brothers in our brigade, though with different names, who had been killed; Goade, 13th, being Bradford's brother, and Lockwood, Wood's brother, and their deaths were announced by me to their brothers without my knowing the relationship.

Lucan is much cut up; and with tears in his eyes this morning he said how infamous it was to lay the blame on him, and told me what had passed between him and Lord Raglan. The fact is, we can fight better than any other nation, but we have no organisation. At the Alma it was just the same bulldog work, but no orders issued; and so at the commencement of the Peninsular War, and so it will be at Sebastopol. I have always anticipated a disaster when the cavalry came to be engaged, though I kept it to myself. Each of the Earls exculpates the other from blame. How unfortunate the poor cavalry always is, to be either sneered at for being slow, or to get into these scrapes, neither being their own fault! There were not ten men killed by the enemy's cavalry — it was all done by the raking fire from the flanks. Their cavalry proved themselves great curs. A large force of cavalry attacked the 93rd, who allowed them to come up quite close, and then cave them such a fire that they flew back across the plain. It was not a pleasant morning seeing all our outworks (Turkish) abandoned, and no support coming up from behind. Many an anxious look did I give to those hills.

I paraded the five regiments this morning and formed them into two squadrons. You should hear my voice after holloaing yesterday; it is like an old crow!

Oct. 27. — No attack to-day. It is said we shall give up Balaclava. There was a handsome affair yesterday afternoon, a sortie driven back by our pickets with great slaughter, and little loss on our side. The expression of feelings from you all quite overwhelms me. All that afternoon we, kept feeling over our arms and legs, thinking we must find a sore somewhere. I have just seen our return:

| Officers | killed | 10 | wounded | 21 | |

| Men | " | 138 | " | 270 | |

| 148 | 291 | ||||

| Horses wounded 379 | |||||

out of about 630 on parade in the morning. All the shipping nearly is out of Balaclava, and the hospitals ordered to be ready for a move. "Annihilation of the Light Cavalry Brigade," will figure some morning probably in the newspapers in large letters. How we dread this for you all! Lord Raglan rode through our camp this afternoon, which caused some excitement among our fellows, rushing out to cheer him in their shirt-sleeves. But he did not say anything. How I longed for him to do so, as I walked by his horse's head! One little word, "Well, my boys, you have done well," or something of the sort, would have cheered us all up, but then it would have entailed on him more cheers, which would have been distasteful to him; more's the pity, though one cannot but admire such a nature.

Oct. 27, evening. — The Scots Greys puzzle the enemy. They think we mounted the Guards on horseback.

Oct. 28. — I was abruptly interrupted in my letter last night by a turn out at 10.30, in consequence of the guns on our heights opening fire. We were only out for an hour, but were roused out again by another alarm at 4 a.m., when there was heavy cannonading for half an hour, and when day began to break we found that the rumpus was caused by a number of Russian horses (with the kits on) having broken from their own lines, and rushed by our pickets. They were afterwards secured, 150 in all, mostly small greys. This was the third surprise we had yesterday (the first at 9 a.m.), which is no joke. The sensation created by night alarms is unlike anything else. The holloaing, the hurry, the rushing about, the trumpet-sounds, and the cries of "lights out" (that is the first cry always), with probably musket and cannon in the distance, is very exciting in the pitch-dark; but at last one gets accustomed to it, though one ends by jumping up at the least sound.

I am glad to say we are in a less exposed position to-day, having moved on to the steppe, land, looking over the lain at the end what is called the "Col de Balaclava." I think that I may have been instrumental in this move, having represented to Lord Raglan the other day the impropriety of leaving us always, or rather our camp, in such exposed positions. It is a fact, that we have till now been generally encamped in an outside position, i.e. with nothing in front of us. Cavalry when mounted should be outside of every thing, but their camps should always be inside, for when in camp (at night) they are helpless, and subject to disaster. So little is this appreciated, that (if report speaks truly) there was at one time a question of whether we should be encamped under Cathcart's Hill — "en l'air" — as it were.

A flag of truce went to-day to Liprandi to ask about our wounded. Alas! only three officers alive, and another goes to-morrow to ascertain their names. All the officers were very civil, except one fat old general, who, in answer to the question whether if all the dead were not buried we might be allowed to do so, said, "Dites à Lord Raglan, que nous sommes Chrétiens; nous nous battons, mais nous sommes Chrétiens." ["Tell Lord Raglan, that we are Christians; we fight, but we are Christians"] The valley is covered with dead horses.

Evans' Division gave them a rare slating on the 26th. But the siege, in the meantime, don't make much progress. I hear Lord Raglan has written home a rattling despatch about us. How absurd it will be wearing badges hereafter for Alma and Sebastopol when we did nothing, and having nothing to show for Balaclava! They are going to take my Russian horse from me. All the horses taken are to be handed over to remount the Light Brigade; but I shall make a push for mine, particularly as my horse is lame after Balaclava.

Oct. 30. — Such bitter cold, I and the snow has begun to show on the hills. There is little doubt now, I fear, of the army's wintering in the Crimea. An order has come that now that we are within the lines we are only to turn out at 5.30 every morning. Imagine this being a source of rejoicing!

Oct. 31. — Airey told me to-day they are preparing for hutting for the winter. We have been selling to-day the effects of those who fell on the 25th. Melancholy work. A surprise again at 11 p.m. General Bosquet, it appears, had set his eye upon a nice lot of cavalry horses, and sent a shell into them, and succeeded in getting some. A novel expedient truly, but he might as well have given us warning, and thus have saved us our turn out in the cold. Very little firing to-day; we are, I fancy, running short of ammunition.

Nov. 1. — It has become so cold, with a piercing north wind. The thing I find most difficult in keeping, warm at night is my nose, and I fear it will affect its beauty.

The deserters say they are nearly all starving in Sebastopol, but well clothed. As for our horses, another week will finish them.

Nov. 2. — To-day we, the Light Brigade, have moved to about where, we (the 4th) were a fortnight ago, when attached to the Second Division close to the windmill. Why, I don't know. On arriving at our encamping ground, I found "the Punter" (Colonel Blair, Fusilier Guards, killed at Inkermann.) waiting to tell me, that he had prepared dinner for me, and we had a very sumptuous spread, after which we, adjourned to the Duke of Cambridge's tent, and smoked a cigar with him, the subject of course being Balaclava, of which — or rather of one's constant repetition of the same story — one is beginning to get tired. Turning round in one's narrow bed is a difficult operation, without disarranging the economy of the blanket, plaid, great coat, and cloak; and there is always an odd knee or toe, or some stray corner of one's body, that one cannot keep warm.

Nov. 3. — Nothing fresh; all reports so contradictory, that one knows not what to believe. I am left in a sort of command of the brigade, as Cardigan is ill on board his yacht, though he comes up most days. He is an odd man, certainly. When I first joined the brigade, ten days ago, I pointed out that the brigade was not placed in camp as it should be according to rule; since then he has given in to my views, and yesterday, on our taking up our ground, he said, "Here, Lord George, you seem to understand these things; be good enough to picket the brigade according to your ideas;" but whether this was because he was cold or bored, or had confidence in me, I am not prepared to say.

Nov. 4 — We have had such a drenching day, at least morning, for it cleared up at one, and there has been very little firing. A rainy day in camp is no joke. The Great Duke never said a truer thing than that the worst house is better than the best tent; but we have an additional blanket issued to-day.

Nov. 5, evening. — Another dreadful struggle just over. The enemy attacked our position at daybreak this morning, and the fight has been going on all day. Ours has been a complete victory; but at what a sacrifice of life! Eight generals hors de combat! A more sanguinary day than the Alma. The Light Cavalry Brigade were sitting under a heavy fire for half an hour, and lost a few men.

Early in the morning Nigel Kingscote (Colonel Kingscote, one of Lord Raglan's aides-de-camp) rode up to me, and told me that I was to support the Chasseurs d'Afrique, in case they were called upon. This they soon were, and went to the front, to the support (as we heard) of General Bosquet, whose division was in difficulty. We went on till we got into a heavy fire, when after some time they returned, and we also. We advanced nearly as far as the two great batteries, and there saw a scene of carnage I shall not easily forget.

At one moment I fell in with the Duke of Cambridge, and said, "Where are the Guards?" when he, pointing out a small cluster of men, said "There they are, all that are left of them."

Nov. 7. — There is nothing new. We are gradually settling down after the shock of Sunday. It was indeed a dearly-bought victory, and would not have been one, but that "Englishmen never know when they are licked," as Napoleon I., I believe, said. Pennefather told me the loss of the Russians must have been 20,000. As usual, our fellows had to bear the brunt of it, though some French troops came to our assistance at last. A Council of War, yesterday, adjourned to to-day. They attacked us in that part of our position which was considered the weakest; and since the battle we have been intrenching it more. We are in the thick of all the horrors here, our encampment being close to the windmill, the depôt of the wounded Russians, half an acre of which (enclosed in a stone wall) is filled with them.

Here, again, my orderly was killed; there seems to be a fatality about my followers. They all get knocked over, and there was something peculiarly unlucky in the fate of this one, Rickman by name. Perceiving that he was not wounded when we turned out in the morning, I asked his captain (Brown) why he was not out. He said, "There must be some mistake, as a horse was told off for him;" and he accordingly mounted. I have of course nothing on my conscience, still the reflection is painful.

The evening after the battle, I smoked a cigar with the Duke of Cambridge in his tent. Poor Clifton was there, with a dreadfully swollen face, having been hit on the cheek. Jem Macdonald, as usual, cheery. Bentinck, when being carried past us wounded, said, "Ah, it is my turn now!" The shoals of wounded being carried past us all day was truly distressing. Oh war! war! how one has heard and read of it without realising all its horrors! I must stop now, but I intend, D.V. [Deo volente --God willing], to write, a more detailed account some day of all that I saw in this battle, as well as Balaclava.

Nov. 7. — Went to head-quarters to hear the result of the Council of War, as to what was decided on for the future, as upon that depended the questions of whether I should ask leave to go home, with the purpose of retiring from the service; and the same evening I dined with the Duke of Cambridge, and discussed the matter with him, and Jem Macdonald.

Nov. 8. — The Council of War has determined that the siege, or rather assault, is to be given up for the year, and until reinforcements come; and that the occupations of the army are to be for the present confined to intrenching themselves strongly in their position.

Nov. 9. — Went to Lord Raglan, and after a conversation with him and Estcourt, it was agreed that there could be no objection to my going home, for the purpose of retiring; and he then called for the Order Book, and himself wrote down the order giving me leave for this purpose. [Paget's father had just died]

I rode down to Balaclava, and secured a passage on board the Andes, and then returned to my camp and packed up my traps. After which, I ordered a parade of the regiment, and gave them a parting address, which was warmly responded to; and they turned out, as I rode away, and gave me three cheers. I then rode back to Lord Raglan to dinner.

In the middle of it a large, official letter was brought to him (which had been opened). It was from Menschikoff, and addressed to Lord Raglan and Canrobert conjointly, having come first to Lord Raglan, and been sent by the latter to Canrobert to open, from whom it was now returned. It was in answer to one sent by them to Menschikoff, complaining of the wounded having been bayoneted at Inkermann, the tone of which answer may be judged of by Lord Raglan's remark on reading it, and handing it to us to read, "Not a very satisfactory letter, I think." It was in courteous terms, but taking the high line, contradicting the assertion, but saying, "At the same time that, if such acts had been committed, they would have been justified by the previous acts of the Allies, in having fired on a church in the town."

About 11 p.m., I took my leave and started in a very thick fog for Balaclava, to which I had great difficulty in finding my way, though accompanied by a corporal of Lord Raglan's escort who knew it better than I did. On my road, I called at Lord Lucan's tent, and found him in bed, but had an equally warm parting with him, and many kind expressions as to the way in which I had served under him.

Nov. 10 — Blew so hard that we could not get out of the harbour. I could not get far away for fear of missing the ship sailing.

Nov. 11. — The weather moderated, so we sailed at 1 p.m. to-day in the Andes, and soon lost sight of our enemy's coast.

Notes

(1) In saying this, I meant nothing as regards Lord Lucan. I always received every consideration from him, and there was no one under whom I would rather serve; but I certainly had misgivings as to my position relatively to him and Lord Cardigan combined.

It was once said of two noble lords, who betted heavily on the turf, and who were much associated in their dealings therein, while at the same time they were supposed to be not over scrupulous with others, " They are like a pair of scissors, which go snip and snip and snip, without ever doing each other any harm, but God help the poor devil who ever gets between them! " And this, I thought, might possibly apply to my case. [back]

Last modified 29 May 2002