Peter W. Sinnema's study of the relation between national mourning for the Duke of Wellington and English identity at mid-nineteenth century arrived at the Victorian Web within a short time of a number of several closely related contributions: Philip V. Allingham, our Canadian contributing editor, had sent in scanned images and text from both The Illustrated London News's series of articles on the funeral of the Iron Duke and that periodical's coverage of the Great Exhibition of 1851 to which The Wake of Wellington devotes one of its seven chapters. Not long before,

Jacqueline Banerjee, our contributing editor from the UK, had sent in a series of photographs and accompanying text on various memorials related to Wellington, including Sir Richard Westmacott's Achilles, the Wellington monument in Hyde Park, and Decimus Burton's Wellington (or Constitution) Arch, once the site on which perched Thomas Wyatt's grotesquely large equestrian statue of the Duke. These provided the subject of Sinnema's closing chapter. There were other points of coincidence: I had just reviewed a recent book on Joseph Paxton that approaches the Crystal Palace from a very different direction from Sinnema's, and over previous months I had written several dozen brief discussions of both Thomas Brown's School Days, the point of departure for the first chapter, and Thomas Arnold, who is the true hero and moral center of the book. I therefore eagerly looked forward to reading The Wake of Wellington.

Peter W. Sinnema's study of the relation between national mourning for the Duke of Wellington and English identity at mid-nineteenth century arrived at the Victorian Web within a short time of a number of several closely related contributions: Philip V. Allingham, our Canadian contributing editor, had sent in scanned images and text from both The Illustrated London News's series of articles on the funeral of the Iron Duke and that periodical's coverage of the Great Exhibition of 1851 to which The Wake of Wellington devotes one of its seven chapters. Not long before,

Jacqueline Banerjee, our contributing editor from the UK, had sent in a series of photographs and accompanying text on various memorials related to Wellington, including Sir Richard Westmacott's Achilles, the Wellington monument in Hyde Park, and Decimus Burton's Wellington (or Constitution) Arch, once the site on which perched Thomas Wyatt's grotesquely large equestrian statue of the Duke. These provided the subject of Sinnema's closing chapter. There were other points of coincidence: I had just reviewed a recent book on Joseph Paxton that approaches the Crystal Palace from a very different direction from Sinnema's, and over previous months I had written several dozen brief discussions of both Thomas Brown's School Days, the point of departure for the first chapter, and Thomas Arnold, who is the true hero and moral center of the book. I therefore eagerly looked forward to reading The Wake of Wellington.

After a first chapter that looks at Tom Brown's School Days and biographies of Wellington, the book examines the Great Exhibition of 1851 as an anticipation of the kind of massive public ritual that was the Iron Duke's funeral and also for his role, a very characteristic one, in organizing security for it. Next, Sinnema looks at the way periodicals and later biographies created a picture of Wellington's austere, simple life, after which a fascinating fourth chapter juxtaposes the commodification of Wellington in an enormous number of souvenirs and commercial products with what seems an inevitable corollary — a fear of the very masses who were supposed to purchase such memorabilia. Chapter five, "Obsequies and Sanctification," covers exactly what it suggests, and Chapter six, "Irish Opposition," explores the complex Irish reactions to both Wellington and British treatment of this conservative man of Anglo-Irish origins. A final chapter looks at the controversy over the creation of Wyatt's monstrously out-of-scale equestrian statue of the Duke, its critical reception, and its final removal from Burton's arch during Wellington's own lifetime. Throughout Sinemma writes clearly and with not all that much jargon, keeping his argument to a brief 130 pages, including 21 nicely reproduced illustrations, largely from Punch and The Illustrated London News. Sinnema offers valuable insights not only about Victorian conceptions (and myths) of Englishness but also about the prehistory of modern mass-media celebrity. Such an approach is not of course entirely new, since as the author generously acknowledges, similar work on the death of Queen Charlotte in 1815 and the 1851 exhibition pioneered this kind of historical investigation. The brief chapters on the Great Exhibition and the creation of an idealized portrait of the Duke's simple, sparse life and avoidance of luxury work very well, though I would have liked some attempt to place him in the context of ancient Roman history and patriotism. Sinnema's discussion of Irish attitudes toward Wellington economically portrays his homeland's ambivalence toward this conservative Tory: some Irish journalists scoffed at the Duke and English adulation of him while others claimed his virtues derived from Irishness, not Englishness. The English also had to come to terms with the fact that their ideal Englishman was born in Ireland.

For all its virtues, among which concision and generosity toward other scholars hardly rank least, The Wake of Wellington staggers a bit in the first chapter before later hitting its stride. Having just completed several months reading Tom Brown's School Days, Tom Brown at Oxford, The Scouring of the White Horse, and works about Hughes, I found myself somewhat taken aback and chastened by the book's first chapter: how could I have missed what Sinnema claimed to be a central emphasis upon Wellington in Hughes's most famous novel? I began reading The Wake of Wellington in Madrid, where I had gone to give a talk on digital information technologies in the study of comparative literature, and so I was far from my and my university's library, but, most appropriately, given my reasons for being away from home, I had an electronic copy of Thomas Brown's School Days on my laptop, so I decided to search for "Wellington" and found precisely . . . one mention and that in the book's first paragraph, which I shall quote in full:

The Browns have become illustrious by the pen of Thackeray and the pencil of Doyle, within the memory of the young gentlemen who are now matriculating at the universities. Notwithstanding the well-merited but late fame which has now fallen upon them, any one at all acquainted with the family must feel that much has yet to be written and said before the British nation will be properly sensible of how much of its greatness it owes to the Browns. For centuries, in their quiet, dogged, homespun way, they have been subduing the earth in most English counties, and leaving their mark in American forests and Australian uplands. Wherever the fleets and armies of England have won renown, there stalwart sons of the Browns have done yeomen's work. With the yew bow and cloth-yard shaft at Cressy and Agincourt—with the brown bill and pike under the brave Lord Willoughby—with culverin and demi-culverin against Spaniards and Dutchmen—with hand-grenade and sabre, and musket and bayonet, under Rodney and St. Vincent, Wolfe and Moore, Nelson and Wellington, they have carried their lives in their hands, getting hard knocks and hard work in plenty—which was on the whole what they looked for, and the best thing for them—and little praise or pudding, which indeed they, and most of us, are better without. Talbots and Stanleys, St. Maurs, and such-like folk, have led armies and made laws time out of mind; but those noble families would be somewhat astounded — if the accounts ever came to be fairly taken—to find how small their work for England has been by the side of that of the Browns.

Yes, this passage does emphasize this family's role in establishing the British empire, and, yes, Wellington, receives mention along with five other British military heroes, but it in no way holds Wellington or any other much-praised heroes up to the reader as an ideal. Instead, Hughes emphasizes the importance to England of this family of yeoman who "have carried their lives in their hands, getting hard knocks and hard work in plenty — which was on the whole what they looked for, and the best thing for them — and little praise or pudding, which indeed they, and most of us, are better without." Hughes's ideal Englishman in fact turns out to have little in common with the Iron Duke. In fact, if one looks at Tom Brown, the novel's protagonist, its portrayal of Thomas Arnold, and the author's own career, one receives a vastly different impression of the novel and its author from what Sinnema suggests. To begin with, what kind of heroism does Tom, a brash, unthinking boy at the novel's opening, display? After Arnold, his headmaster, confers with the boy's housemaster, they decide that the best way to save Tom from himself is to have him take under his wing a younger boy, the still-grieving son of a clergyman who died taking care of the poor during an epidemic when other ministers and the local physicians abandoned them — a fairly obvious echoing of the Catholic priests praised by Carlyle in Past and Present for doing the same during an epidemic in southern Italy. That example of heroism alone should warn us that Hughes has little interest in the kind of heroism exemplified by Wellington. Tom does defend his charge from a bully, but he displays far greater courage by risking ridicule when he follows little Arthur's example and prays in the dormitory before getting into bed. By the end of the novel, Tom has become a more spiritual, feeling young man ready to learn his final lesson at Rugby: as he takes leave of his housemaster before leaving the school for Oxford, to his great surprise he learns from him that his friendship with Arthur, which has contributed so much to his growth as a person, came about as a result of the headmaster's concern for him. Arnold, who appears throughout the book as a true Carlylean hero, is the moral, ideological center of Tom Brown's School Days — Arnold, the gentle but brave teacher of moral courage that enables Tom and others to go against received opinion. Yes, Hughes praises athletics as healthy diversion and exercise at Rugby, but he also emphasizes the transience, the essential unimportance, of athletic fame. Nonetheless, even a cursory reading of the novel reveals that although it does mention Wellington and one of his victories in India, Tom Brown's School Days continually emphasizes a very different kind of leader, so different in fact that Sinnema's use of the book in The Wake of Wellington appears a grotesque misinterpretation.

Sinnema's problems with effectively handling evidence at times appears in his occasionally writing as if one can take any statement, however unlikely or oversimplified, that has appeared in print to prove one's argument. He, for example, quotes Norman Thompson that "virtually 'every writer projected onto the Duke of Wellington the demanding ideals of the age and saw in him the perfect hero in Victorian dress: selflessly devoted to his country; modest and heedless of rewards and display; diligent and meticuliously attentive to detail; patient and punctual, temperate and thrifty'" (5). Every writer, really? Was Wellington praised or even mentioned in the works of both Rossettis, both Brownings, both Newmans, Meredith, Thompson, Patmore, Disraeli, Bulwer-Lytton, Collins, Eliot, or Trollope? Tennyson, the recently appointed Poet Laureate, of course wrote his ode on Wellington, but that was part of his job, that is what he was paid to do. And Dickens, an important journalist as well as novelist, certainly might have commented on the Duke, though I don't recall Sinnema citing any examples of his having done so. Ruskin sharply differed from Carlyle's positive estimate of Wellington, going so far as to question whether he should even receive credit for the costly victory at Waterlooo! My point here is that no need exists for such exaggeration, which ends up greatly weakening the author's credibility, when he already has a strong case.

Here, also from the first chapter, is another troubling example of his accepting as authoritative a strong but hardly convincing statement to support his own positions.

In the nineteenth century, as David Morse has argued, to be English was to not be myriad others and other things. Englishness, as he puts it, "means to be English, as against Irish, Scottish, or Welsh, to be Saxon rather than Celt; it designates the interests of the aristocracy and the middle class, which have to be defended against the workers; it means having property and 'a stake in society'; it is also to be Anglican rather than a Catholic or a Dissenter; to be male rather than female; to be law-abiding and opposed to violence; it is to be respectable and contented rather than disreputable and discontented."

The Wellington with whom English mourners were asked to identify at the funeral and in most of the posthumous literature was therefore not simply the virtuous man of patriotic duty and devotion to the Crown but also the blue-blooded, unpretending, antirevolutionary, decidedly un-Celtic hero whose birth to Anglo-Irish peers in Dublin did nothing to prevent the Times from insisting on his being English "to the very heart's core." [11]

A good many upper-class Englishmen and women might have embraced such a narrow view of Englishness, but the evidence of those people Sinnema cites in this chapter shows how misleading is the claim made by the passage. Carlyle, for example, remained aggressively Scottish his entire life, retaining his accent. Equally important, although the first Victorian sage moved from radical acceptance of revolutionary violence in The French Revolution to reactionary and racist positions, loathed the British aristocracy, famously asking what they were doing while their country experienced multiple crises and answering that — they were "protecting their game." Hughes, that celebrant of Englishness, showed his harshly anti-aristocratic views in Tom Brown at Oxford, and in The Scouring of the White Horse he emphasized local working-class country customs as the sort of Englishness worthy of preservation. Turning to Hughes's career, we find someone about as far from the passage's ideas of Englishness as one could imagine. When I first reread Tom Brown's School Days and the Oxford sequel, I took Hughes to be primarily an author of books for boys, but a look at his publications and career reveal a very different person from the one that a reader might guess from Sinnema's use of his work. First of all, Hughes, a believer in Arnold's social activism, with others founded the Workingmen's College and between 1872 and 1883 served as the principal of the Workingman's College at which Ruskin and others taught. Probably one of the very few graduates of a public school who sympathized with the Chartists, this attorney devoted much of his life to the cause of unionization, particularly to legislation that made modern unions legal in the U.K. One of his publications, A Manual for Co-operators, falls about as far from the beliefs of Wellington, who opposed the first Reform Bill and tried to crush the Chartists, as one could find!

These problems appear in the first chapter, which may have the unfortunate result of so weakening Sinnema's credibility in the eyes of readers that they will not continue reading what is in fact a concise, well-written volume that offers a way into the mind and heart of England at mid-nineteenth century while showing the rise of modern conceptions — and political uses of — celebrity.

Madrid-Providence 27 September 2006

Related Materials

- Speech on Catholic Emancipation (April 2, 1829)

- A Response to the King's Speech in the House of Lords (2 November 1830)

- On the repeal of the Corn Laws (28 May 1846)

- Field-Marshall His Grace the Duke of Wellington by Sir Thomas Lawrence

- Preparations in St. Paul's Cathedral for the Funeral of the Duke

Bibliography

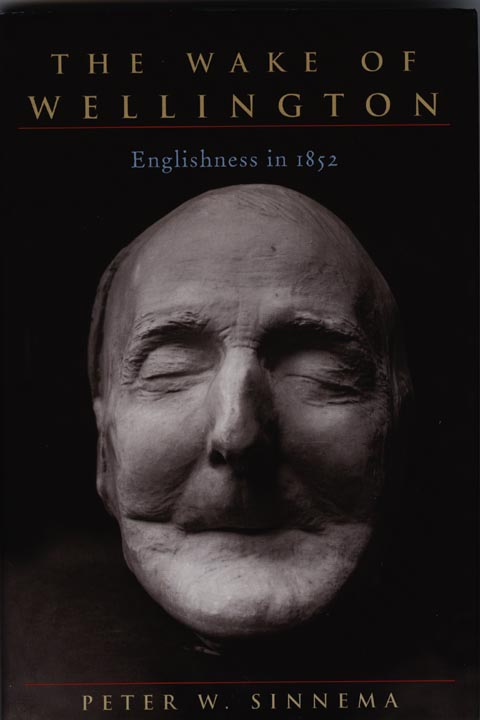

Sinnema, Peter W. The Wake of Wellington: Englishness in 1852. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2006.

Last modified 27 September 2006