Harriet Hosmer's Queen Zenobia

Meredith Moore '08, English 156 (History of Art 152) — Victorians in Togas: Classicism and Empire in Victorian Literature and Art, Brown University

[Home —> Visual Arts —> Sculpture —> Painting —> The Nude in Victorian Art]

Harriet Hosmer defied the commonly held idea that sculpture was physically beyond a woman's capabilities. Known as an 'emancipated female' for her radical behavior of living alone, walking alone, and riding horseback alone, Hosmer soon gained a reputation not only asa talented sculptor but also as a pioneering advocate for women's rights.

Hosmer began her career at age 19, and in 1852 moved to Rome to study under English Sculptor John Gibson. Hosmer worked in the contemporary neoclassical style, although her works revealed an approach to content that was noticeably different to that of her contemporaries. Most of her subjects such as Daphne, Medusa, and Oenone depicted figures and themes of classical mythology. Hosmer's preference for female subjects has been understood as a reflection of her concern for the secondary status of women in the nineteenth century. This is particularly evident in her monumental work of Zenobia, the 3rd century Queen of Palmrya.

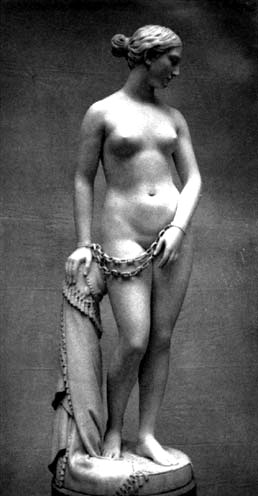

Known for her courage, intelligence and beauty, Queen Zenobia reigned over Palmyra from 267 to 272 A.D., and the city flourished under her rule. In 270, when Aurelian came to power in Rome, Palmyra was sacked and the Queen was captured. The sculpture done by Hosmer in 1859 depicts Zenobia as a captive to the Roman army. The fallen queen stands defeated; head slightly bowed, and eyes downcast. Her crown, jewels and impeccably gathered dress appear unaffected despite the heavy chain, which hangs from her wrists, the only symbol of her imprisonment. Her stance still conveys power, her back is straight and her shoulders are back as she slightly steps forward with confidence. Contrasting comparable works portraying suffering women, such as Hiram Powers' The Greek Slave, 1843, Hosmer shows the queen clothed, proud, and stoic.

Left: The Greek Slave by Hiram Powers. Right: Zenobia by Harriet Hosmer.

Click on thumbnails for larger images.

Hosmer employed multiple literary and historical accounts of the queen to construct her visual representation. It is a common held belief that Hosmer relied upon Augustan History and William Ware's novel, The Letters of Lucius Piso, to develop her Zenobia (Waller 22). In these male accounts of the Queen, she is said to have been, "decked with jewels and golden chains, for which she labored under weight of the ornaments; for it is said that this woman, courageous though she was, halted very frequently, saying that she could not endure the weight of her gems" (Waller 23). Hosmer's depiction, however, does not follow these descriptions of the Queen. Hosmer diminishes the chains to only wrist manacles and lessens the jewelry to only that which is necessary to convey her royalty. The Queen does not appear faint nor does she falter as she confidently steps forward. In Hosmer's account, the Queen is calm and dignified; she is in an active pose, clutching her chains embodying strength and authority. Hosmer chose to bring Zenobia to life, not as her usual symbol of a defeated victim, but rather as an embodiment of woman's ability to move beyond the constraints that have been placed on them.

Questions

Left: The Barberini Juno. Right: The Athena Giustiani

1. Do you see any possible similarities between these two classical sculptures and Hosmer's Zenboia, the Athena Giustiniani and the Barberini Juno?

2. In your opinion does Hosmer portray Zenobia as a strong and authoritative figure? If not, how could she have done so?

3. Do you feel it is acceptable for artists such as Hosmer to alter historical accounts of figures to better suit the idea they are trying to convey?

Bibliography

Waller, Susan. "The Artist, the Writer, and the Queen: Hosmer, Jameson, and Zenobia." Woman's Art Journal 4.1 (1983): 21-28. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0270-7993%28198321%2F22%294%3A1%3C21%3ATATWAT%3E2.0.CO%3B2-3

Last modified 27 February 2007