Court of Small Causes, Calcutta (as it was then), designed by William Henry White, F.R.I.B.A. Source The Builder, 23 March 2025, p. 297.

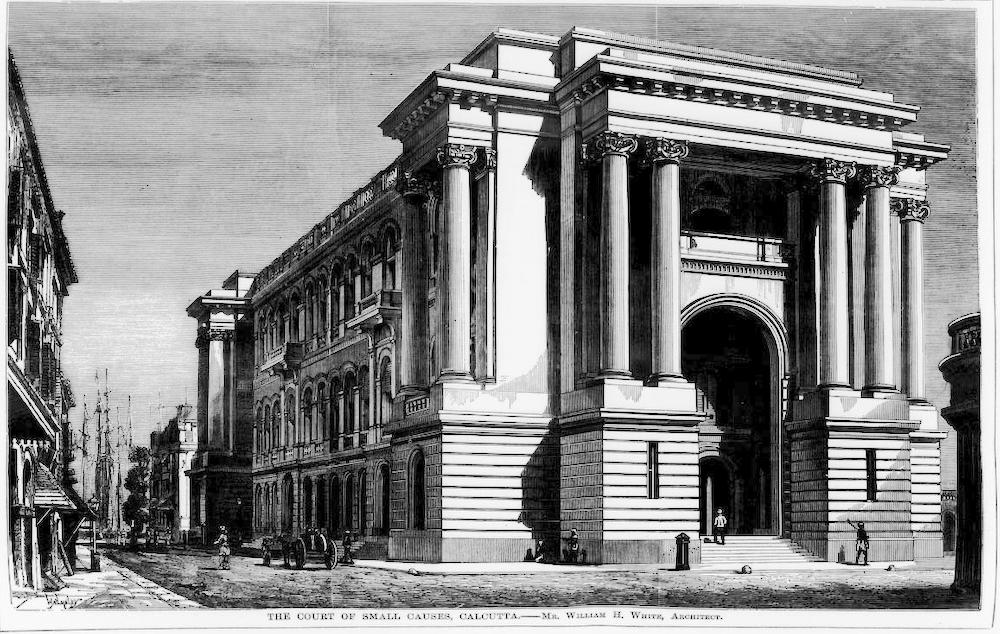

Philip Davies writes that White was in India, attached to the P.W.D., for thirteen months in the later 1870s. One of his major projects, in fact the only one he completed, was the Court of Small Causes, close to Walter Granville's neo-Gothic High Court there. However, the "Small Causes" court contrasted with Granville's neo-Gothic complex, since it was in a French Palladian style as "seen through Victorian eyes ... a bold, imaginative and functional building of considerable merit" (Davies 208). Davies regrets that White returned to England after this, and indeed it seems a shame that he came to prominence there for his role at the RIBA rather than for his architectural achievements.

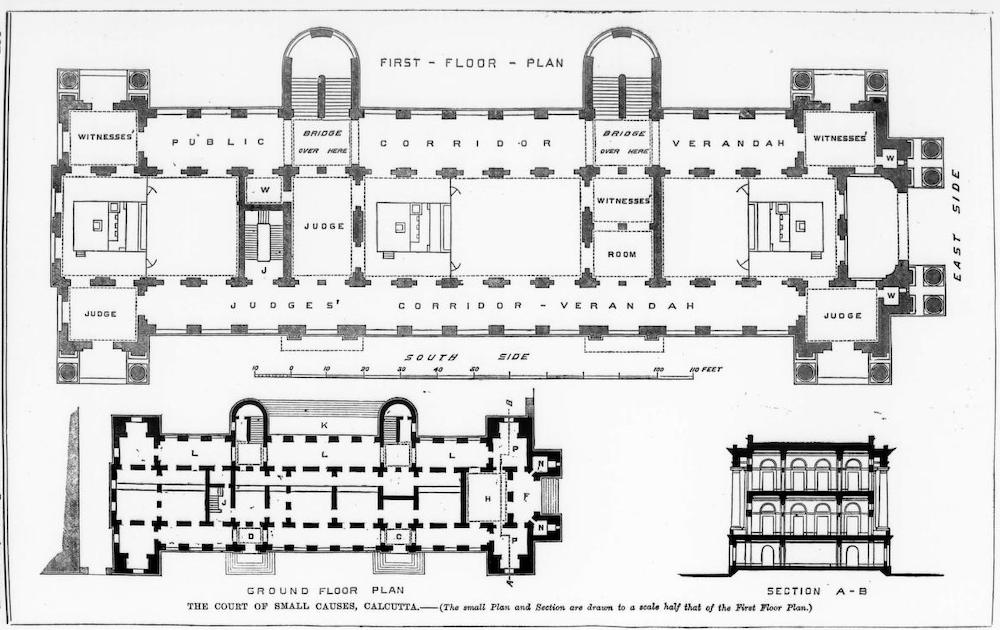

The building and its plans were shown and discussed, with input from White himself, in the Builder of March 1878. It is described as "a Calcutta Court of Justice, consisting of six courts, in five of which judges preside, and of public offices connected therewith" (300), and as having been begun to White's drawings at the end of 1872, and built from 1873-34. The engineer in charge at that time was one Hugh Leonard (1823-1901), "known as the father of Indian engineering, and who was then officiating Chief Engineer and Secretary to the Government of Bengal" (300). The materials were brick with a cement facing, and to the Builder its European exterior was offset by the "Anglo-Indian" character of the courts and verandahs, typical of the town. The south elevation is on Hare Street, and the east on Bankshall Street, where it stood at that time in relative isolation.

The court's location was chosen for the breeze from the Hoogly river to reach the verandahs — a major consideration on that climate. Climate was a decisive factor in the fenestration too, and what might seem rather fashionable French features were in fact essential for the cooling of the building. Much is made in this account of such practical considerations, including the sanitary arrangements, and the various arrangements for clients, advocates, pleaders, officials, clerks, and of course the public.

The plans show separate corridors for the judges and the public, separate holding rooms for the witnesses, the concern for ventilation, etc. All is clear and well thought out.

One much regretted shortcoming was the absence of porticos over two entrances, not the architect's fault but a cost-cutting measure. ("the Government of Bengal would have no porches or porticos," 300). Aspersions are cast here on the quality of the new buildings in what was then the capital of the Raj, especially in comparison with Bombay. Interestingly, the factors blamed here are inferior materials, and the failure of Calcutta's P.W.D. to retain top-notch civil architects. Certainly, Mumbai outshines Kolkata today, when it comes to architectural heritage. White himself commented on the problems for architects in Calcutta:

During the thirteen months I was in the service of the Government,” said Mr. White, “two large public buildings were commenced. The plans, sections, and elevations of one of them, with an approximate estimate, having been approved by the Lieut.-Governor, were sent by the Superintending Engineer of the Presidency Circle to an Executive Engineer, with orders to prepare an official estimate, and to commence the works without delay; at the same time he was cautioned as to the precarious nature of the soil and ordered to make plans and sections of the necessary foundations, the footings of which were to be calculated, as regards width and depth, according to the weight of wall they were intended to carry. The plans and sections of those foundations, with a careful estimate of their cost, were, in due time, sent to the Superintending Engineer, approved by the Chief, and returned to the Executive Engineer, with orders to begin. Those foundations were barely completed before a change was necessitated by unexpected circumstances. The Executive Engineer, who had given a great deal of conscientious labour to the study of them, and who was responsible for them, was suddenly despatched to the charge of a division distant 1,000 miles from Calcutta; another was appointed to the post thus vacated, and the works proceeded. Now it is clear that if those foundations fail, the original Executive Engineer cannot be called to account, because his mantle of responsibility was transferred to the shoulders of the colleague who superseded him; while each of the Executive Engineers who have continued the works can plead, in the event of the failure of any portion of them, that it is due to the foundations which their original predecessor executed. Another illustration of the difficulty,” continued the narrator, “of defining responsibility is to be found in the New Imperial Museum of Calcutta, the original design for which was made by the late Mr. Granville. Some of the floors of that building were designed to be arched and the passages vaulted. Soon after the works were commenced, an order was issued to substitute iron girders in their place; and walls designed to receive continuous brick arches were weighted at intervals with enormous wrought-iron girders. The obvious consequences followed, and the building is ruptured in many places...." [300-301]

Such a way of proceeding would not have pleased a stickler like William Henry White at all. He too was a dissatisfied employee. The writer of the Builder article goes on to say that in the case of the court building, "the general exterior is pretty much as the designs showed it; but refinement or even accuracy of mouldings in the cornices and strings, the necessary entasis to the columns, are conspicuously absent. The balusters, rustications, and the arch-reveals, are by no means orthodox adaptations from the antique, or even the French architecture of the last century" (301). Unlike architectural historian Philip Davies, who complains of the "woefully inadequate attempts of Indian craftsmen" to copy the designs provided for the Ionic capitals (208), this commentator's first response to this particular variation is to see the capitals as "singular examples of ingenuity, and, most likely, native ingenuity.... the native modeller has interpreted the geometrical drawing line for line; he has produced, instead of volutes, four things which seem to be a combination of serpent and dolphin, snake and fish, swathed in a bandage which encircles the capital" (301). Admittedly, the word "things" suggests a certain scorn, so perhaps it is no surprise that the very last sentence of this account is more critical, explaining that the Builder's illustration shows the capitals as they were intended to be — "not as they unfortunately are" (301). Was this in deference to White, who would obviously have preferred his plans to have been carried out to the letter?

We do not know why White left Calcutta after just over a year, but we can guess that he was less than pleased with his experience of working for the P.W.D. there.

Bibliography

"The Court of Small Causes, Calcutta." The Builder Vol 36: 300-301. Internet Archive. Web. 9 July 2025.

Davies, Philip. Splendours of the Raj: British Architecture in India 1660-1947. London: Penguin, 1987.

Hugh Leonard: 1902 Obituary (from the Institution of Civil Engineers). Grace's Guide to British Industrial History. Web. 9 July 2025.

Created 9 July 2025