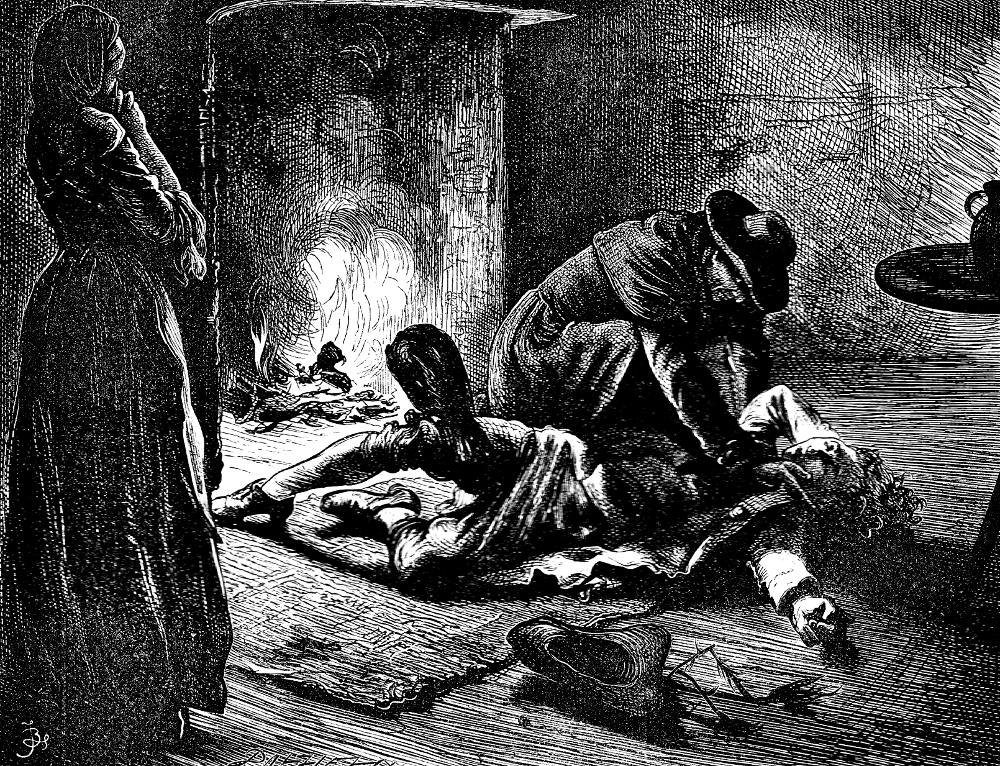

With that he advanced, and bending down over the prostrate form, softly turned back the head by Fred Barnard. 1874. 3 7⁄16 by 5 5⁄16 inches (10.7 cm by 13.7 cm), framed. Dickens's Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty, Chapter XVII, 69. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Context of the Illustration: The Mysterious Stranger confronts his Son

"Stay," he whispered. "You teach your son well."

"I have taught him nothing that you heard to-night. Depart instantly, or I will rouse him."

"You are free to do so. Shall I rouse him?"

"You dare not do that."

"I dare do anything, I have told you. He knows me well, it seems. At least I will know him."

"Would you kill him in his sleep?" cried the widow, throwing herself between them.

"Woman," he returned between his teeth, as he motioned her aside, "I would see him nearer, and I will. If you want one of us to kill the other, wake him."

With that he advanced, and bending down over the prostrate form, softly turned back the head and looked into the face. The light of the fire was upon it, and its every lineament was revealed distinctly. He contemplated it for a brief space, and hastily uprose.

"Observe," he whispered in the widow’s ear: "In him, of whose existence I was ignorant until to-night, I have you in my power. Be careful how you use me. Be careful how you use me. I am destitute and starving, and a wanderer upon the earth. I may take a sure and slow revenge." [Chapter XVII, 69]

Commentary: In the Rudges' Southwark Hovel

Barnard has emphasized the figure of the mysterious stranger in his early illustrations, perhaps because his predecessor, Phiz, had executed the plates involving Barnaby and his mother so effectively. This enigmatic ruffian turns out to be Barnaby's estranged father (whom everyone in Chigwell thinks was murdered twenty-two years earlier). The dark, menacing figure of Old Rudge appears prominently in Barnard's third, eleventh, and twelfth illustrations: "Stand — let me see your face"; "Come, come, master," cried the fellow; and With that he advanced, and bending down over the prostrate form, softly turned back the head. Thus, in the first movement of the story, Chapters One through Seventeen, Barnard makes the aged but street-wise ruffian a continuing and menacing presence. His supposed murder and that of his master, Reuben Haredale, twenty-years earlier constitute an ongoing mystery as the reader waits for somebody to solve the dual homicide and to hold Old Rudge accountable.

Although the text of the novel certainly did not change between 1841 and 1867, its apprehension seems to have shifted from its popular reception as an historical romance (with a pair of couples facing blocking figures) to an exposé of the social and political conditions that spawned the No-Popery riots of 1780 in London. The more modelled and three-dimensional illustrations from 1860 onward reinforce this shift in popular assessment of the novel. For instance, Felix Octavius Carr Darley's 1862 title-page vignettes (see below) treat the figures and situations realistically rather than in the caricatural vein of Phiz, John Leech, and George Cruikshank that dominated book- and periodical illustration in the first half of the nineteenth century on either side of the Atlantic. Whereas Phiz treated Barnaby's homecoming in Chapter 17 as a comic scene on stage, with Old Rudge popping his head out of the closet to better hear his son's account of how he and Hugh had been attempting to trap the highwayman who assaulted Edward Chester the night before, Eytinge in his presentation of the widow and her son eschews such situation comedy and caricatural presentation of the three principals. Barnard's treatment of the situation in Chapter 17 is more intensely emotional but equally realistic as the Household Edition illustration of 1874 exemplifies the New Realism of the Sixties. Barnard, leader of the Sixties Realistic School inaugurated by Fred Walker, here attempts to convey the leverage that Old Rudge is using to extort Mary's financial assistance as he pointedly threatens the life of the sleeping youth.

Relevant Illustrations from the Other Editions, 1841-1910

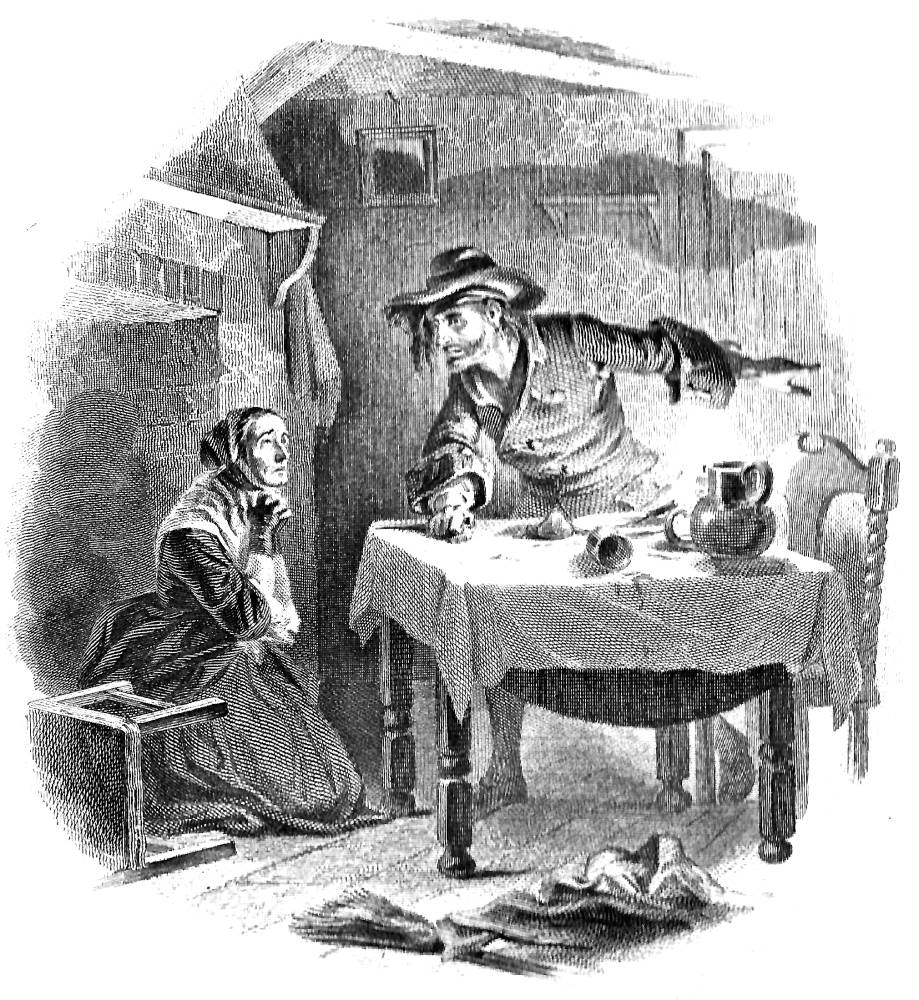

Above: Phiz's less dramatic illustration involving Old Rudge's eavesdropping on the widow and her son: Barnaby Greets His Mother (17 April 1841).

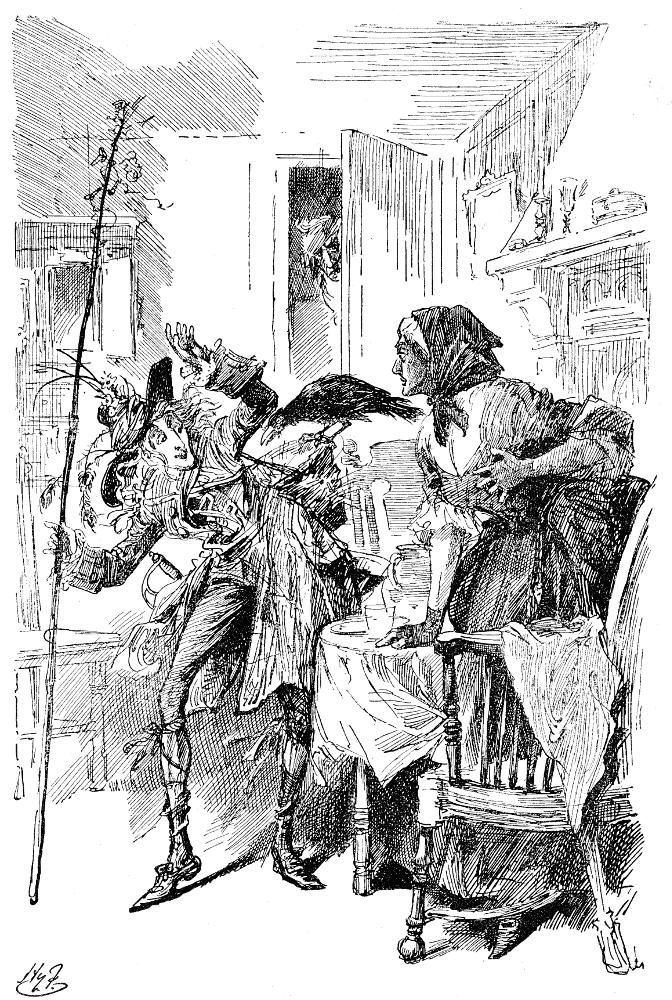

Left: F. O. C. Darley's photogravure title-page vignette of Old Rudge and his estranged wife, "He rattles at the shutters!" cried the man (1862). Centre: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s wood-engraving for the Diamond Edition Barnaby and his Mother (1867). Right: Harry Furniss's lithograph for the Charles Dickens Library Edition Barnaby and his Mother (1910).

Related Material including Other Illustrated Editions of Barnaby Rudge

- Dickens's Barnaby Rudge (homepage)

- Cattermole and Phiz: The First illustrators: A Team Effort by "The Clock Works" (1841)

- Phiz's Original Serial Illustrations (13 Feb.-27 Nov. 1841)

- Cattermole's Seventeen Illustrations (13 Feb.- 27 Nov. 1841)

- Felix Octavius Carr Darley's Six Illustrations (1865 and 1888)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s ten Diamond Edition Illustrations (1867)

- A. H. Buckland's six illustrations for the Collins' Clear-type Pocket Edition (1900)

- Harry Furniss's 28 illustrations for The Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Barnaby Rudge in Master Humphrey's Clock. Illustrated by Phiz and George Cattermole. 3 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1841; rpt., Bradbury and Evans, 1849.

_______. Barnaby Rudge. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

________. Barnaby Rudge — A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874. VII.

________. Barnaby Rudge. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. VI.

________. The Dickens Souvenir Book. London: Chapman & Hall, 1912.

Hammerton, J. A. "Ch. XIV. Barnaby Rudge." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition, illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. 213-55.

Created 20 August 2020

Last modified 18 December 2020