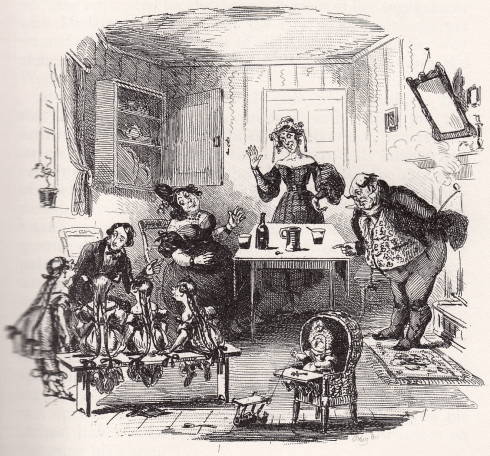

"I can — not help it, and it don’t signify," sobbed Mrs. Kenwigs; "oh! they’re too beautiful to live, much too beautiful!" — Chap. xiv, p. 85, from the Household Edition of Charles Dickens's The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby, illustrated by Fred Barnard with fifty-nine composite woodblock engravings (1875). 10.7 cm high by 13.7 cm wide (4 ¼ by 5 ½ inches). Running head: "Too Beautiful to Live" (85). [Click on the illustrations to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated: Mrs. Kenwigs and her children at her eighth anniversary celebration

Very well and very fast the supper went off; no more serious difficulties occurring, than those which arose from the incessant demand for clean knives and forks; which made poor Mrs. Kenwigs wish, more than once, that private society adopted the principle of schools, and required that every guest should bring his own knife, fork, and spoon; which doubtless would be a great accommodation in many cases, and to no one more so than to the lady and gentleman of the house, especially if the school principle were carried out to the full extent, and the articles were expected, as a matter of delicacy, not to be taken away again.

Everybody having eaten everything, the table was cleared in a most alarming hurry, and with great noise; and the spirits, whereat the eyes of Newman Noggs glistened, being arranged in order, with water both hot and cold, the party composed themselves for conviviality; Mr. Lillyvick being stationed in a large armchair by the fireside, and the four little Kenwigses disposed on a small form in front of the company with their flaxen tails towards them, and their faces to the fire; an arrangement which was no sooner perfected, than Mrs. Kenwigs was overpowered by the feelings of a mother, and fell upon the left shoulder of Mr. Kenwigs dissolved in tears.

"They are so beautiful!" said Mrs. Kenwigs, sobbing.

"Oh, dear," said all the ladies, "so they are! it’s very natural you should feel proud of that; but don’t give way, don’t."

"I can — not help it, and it don’t signify," sobbed Mrs. Kenwigs; "oh! they’re too beautiful to live, much too beautiful!"

On hearing this alarming presentiment of their being doomed to an early death in the flower of their infancy, all four little girls raised a hideous cry, and burying their heads in their mother’s lap simultaneously, screamed until the eight flaxen tails vibrated again; Mrs. Kenwigs meanwhile clasping them alternately to her bosom, with attitudes expressive of distraction, which Miss Petowker herself might have copied.

At length, the anxious mother permitted herself to be soothed into a more tranquil state, and the little Kenwigses, being also composed, were distributed among the company, to prevent the possibility of Mrs. Kenwigs being again overcome by the blaze of their combined beauty. [Chapter XIV, "Having the Misfortune to treat of none but Common People, is necessarily of a Mean and Vulgar Character," 84-85]

Commentary: Domestic Farce in London after the Yorkshire Melodrama

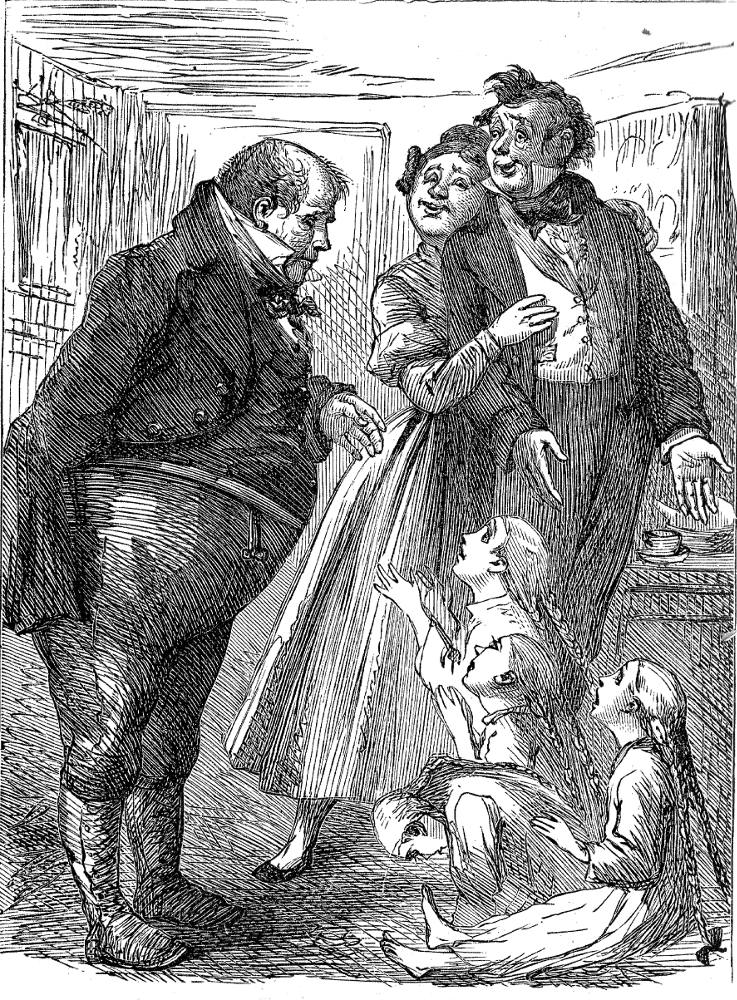

Nicholas Engaged as Tutor in a Private Family (August 1838), in which Phiz depicts Nicholas under the alias "Johnson" as the prospective tutor to the children of a social-climbing London bourgeois couple.

Returned from Yorkshire to London, Nicholas casts about him for a suitable situation, turning down the ignominious position of secretary to Member of Parliament Mr. Gregsbury. However, he agrees to act as private French tutor the daughters of Newman Nogg's neighbours, the Kenwigses, for the sum of five shillings per week. He assumes the name of 'Johnson'.

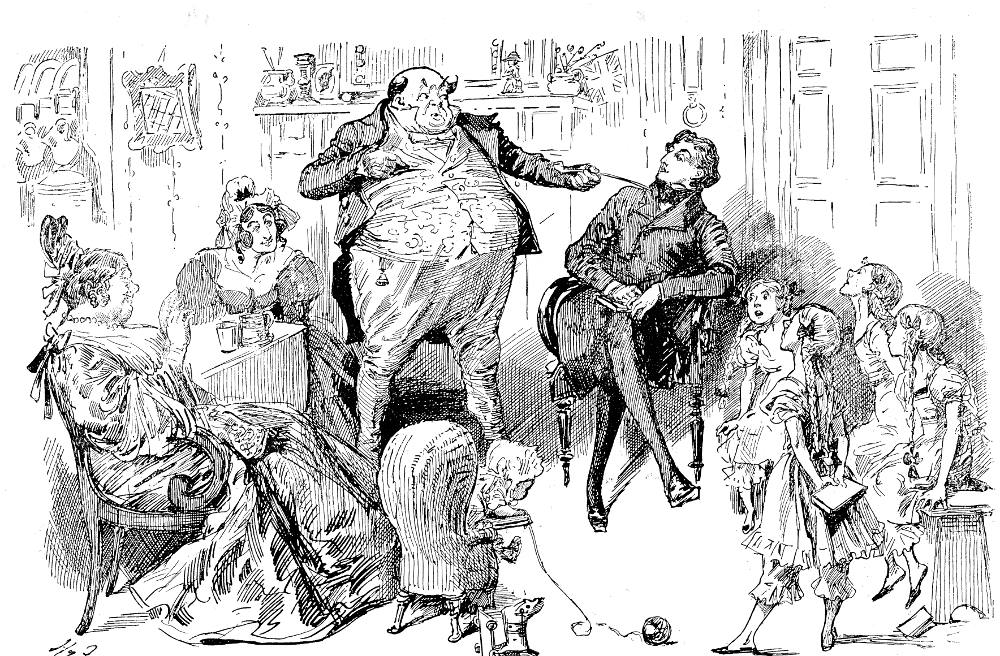

In the 1867 Diamond Edition Sol Eytinge. Jr., makes the rate-collector a dominating and substantial presence in the family portrait: The Kenwigs Family and Mr. Lillyvick (for Chapter 52).

Nicholas meets the Kenwigs family, including Lillyvick, through their mutual acquaintance, Newman Noggs, the Kenwigses' neighbour who lives in the garrett of their building, on the top-most floor. They are having to rent a suite of rooms rather than their own home because they are financially dependant on Susan's rich uncle, Mr. Lillyvick. Because they are determined to retain his favour and inherit his estate, the Kenwigs are constantly ingratiating themselves with him. Consequently they have given their baby the improbable Christian name "Lillyvick." In eight years of marriage, the couple have already had five children; the eldest, Morleena, being an awkward seven-year-old. Focussing on a humorous event that precedes Nicholas's arrival, Barnard targets the serio-comic moment in which the egocentric and self-deluded Mrs. Kenwigs reiterates her conviction that the sheer physical perfection of her offspring will result in their dying in childhood. Behind this odd conviction lies the high infant and child mortality rates then prevalent among the working classes in Britain's urban slums. The minute that Mrs. Kenwigs raises this peculiar complaint, the terrified children begin to cry, sure that some terrible fate is shortly going to overtake them. The picture, then, constitutes a disruption of the conviviality of the anniversary supper and card-game hosted by the middle-class Kenwigs on the first floor of the somewhat run-down, five storey house in Golden Square. Barnard has represented the little girls as being miniatures of Susan Kenwigs herself, in juvenile Regency fashion skirts and feminine trousers. As Kenwigs actually practices a skilled trade as an ivory-turner, he can afford the best apartments in the building, a suite of rooms on the first floor, in which from time time he and his wife entertain her rich uncle in hopes of being left something substantial in his will.

Relevant illustrations from Other Editions (1838, 1875)

Left: The 1875 American Household Edition version of the same by C. S. Reinhart is similarly exploiting the farcical material Dickens has provided: "My baby! My blessed, blessed, blessed, blessed baby!". Right: Harry Furniss's version of the Kenwigses: Nicholas as the tutor to the little Kenwigses (Charles Dickens Library Edition, 1910).

Related material, including front matter and sketches, by other illustrators

- Nicholas Nickleby (homepage)

- Phiz's 38 monthly illustrations for the novel, April 1838-October 1839.

- Cover for monthly parts

- Charles Dickens by Daniel Maclise, engraved by Finden

- "Hush!" said Nicholas, laying his hand upon his shoulder. (Vol. 1, 1861)

- The Rehearsal (Vol. 2, 1861)

- "My son, sir, little Wackford. What do you think of him, sir?" (Vol. 3, 1861)

- Newman had caught up by the nozzle an old pair of bellows . . . (Vol. 4, 1861).

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s 18 Illustrations for the Diamond Edition (1867)

- C. S. Reinhart's 52 Illustrations for the American Household Edition (1875)

- Harry Furniss's 29 illustrations for Nicholas Nickleby in the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

- Kyd's four Player's Cigarette Cards (1910).

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Barnard, J. "Fred" (il.). Charles Dickens's Nicholas Nickleby, with fifty-eight illustrations. The Works of Charles Dickens: The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1875. Volume 15. Rpt. 1890.

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1988.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby. With fifty-two illustrations by C. S. Reinhart. The Household Edition. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1872. I.

__________. Nicholas Nickleby. With 39 illustrations by Hablot K. Browne ("Phiz"). London: Chapman & Hall, 1839.

__________. Nicholas Nickleby. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 4.

__________. "Nicholas Nickleby." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, being eight hundred and sixty-six drawings by Fred Barnard et al.. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1908.

Created 14 April 2021