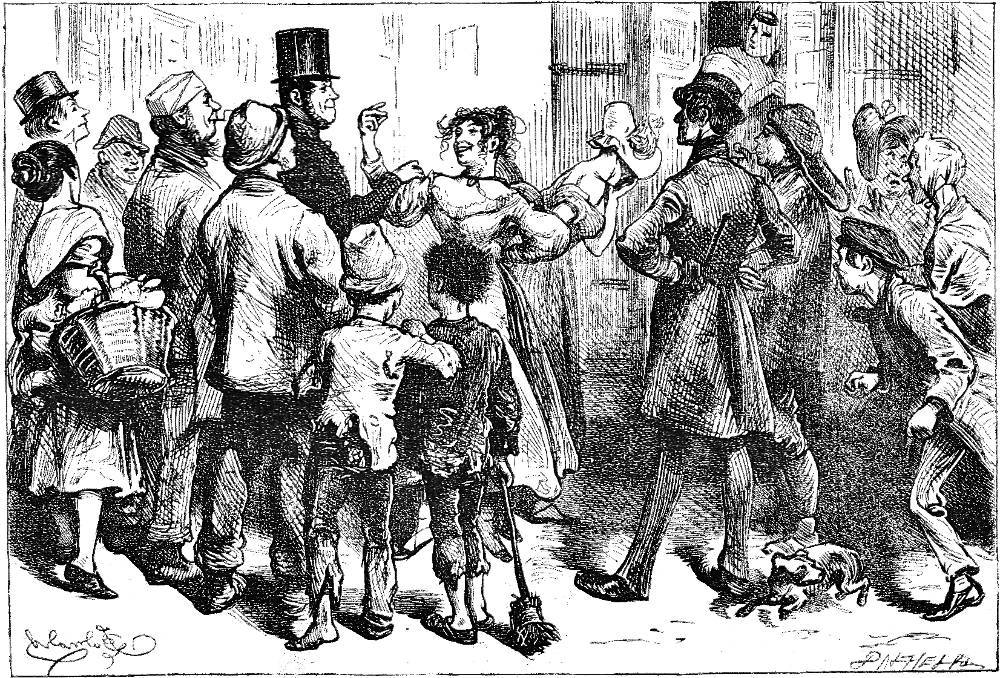

The Prisoners' Van. (wood-engraving). 1876. 9.3 cm high x 13.8 cm wide, framed (p. 132). — Fred Barnard's lively crowd scene in which he contrasts the two sisters arrested as prostitutes, the sixteen-year-old a brazen, cheerful, gesticulating Cockney in the manner of The Artful Dodger in Oliver Twist, and the fourteen-year-old, ashamed, embarrassed, and distraught, as a crowd gathers to watch "her Majesty's carriage" (128) unloaded at the Bow Street Police Office. Whereas Cruikshank had not provided any sort of illustration for the sketch first published as "Scenes and Characters No. 9" in Bell's Life in London on 13 December 1835, and even Harry Furniss did not bother with this slight piece of reportage, Barnard with his strong sense of social justice and interest in the problems of the East End, saw possibilities in the sisters as victims of their neglected upbringing and poverty.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

After a few minutes' delay, the door again opened, and the two first prisoners appeared. They were a couple of girls, of whom the elder — could not be more than sixteen, and the younger of whom had certainly not attained her fourteenth year. That they were sisters, was evident, from the resemblance which still subsisted between them, though two additional years of depravity had fixed their brand upon the elder girl's features, as legibly as if a red-hot iron had seared them. They were both gaudily dressed, the younger one especially; and, although there was a strong similarity between them in both respects, which was rendered the more obvious by their being handcuffed together, it is impossible to conceive a greater contrast than the demeanour of the two presented. The younger girl was weeping bitterly — not for display, or in the hope of producing effect, but for very shame: her face was buried in her handkerchief: and her whole manner was but too expressive of bitter and unavailing sorrow.

"How long are you for, Emily?" screamed a red-faced woman in the crowd. "Six weeks and labour," replied the elder girl with a flaunting laugh; "and that's better than the stone jug anyhow; the mill's a deal better than the Sessions, and here's Bella a-going too for the first time. Hold up your head, you chicken," she continued, boisterously tearing the other girl's handkerchief away; "Hold up your head, and show 'em your face. I an't jealous, but I'm blessed if I an't game!" — "That's right, old gal," exclaimed a man in a paper cap, who, in common with the greater part of the crowd, had been inexpressibly delighted with this little incident. — Right!" replied the girl; "ah, to be sure; what's the odds, eh?" — "Come! In with you," interrupted the driver. "Don't you be in a hurry, coachman," replied the girl, "and recollect I want to be set down in Cold Bath Fields — large house with a high garden-wall in front; you can't mistake it. Hallo. Bella, where are you going to — you'll pull my precious arm off?" This was addressed to the younger girl, who, in her anxiety to hide herself in the caravan, had ascended the steps first, and forgotten the strain upon the handcuff. "Come down, and let's show you the way." And after jerking the miserable girl down with a force which made her stagger on the pavement, she got into the vehicle, and was followed by her wretched companion.

These two girls had been thrown upon London streets, their vices and debauchery, by a sordid and rapacious mother. What the younger girl was then, the elder had been once; and what the elder then was, the younger must soon become. A melancholy prospect, but how surely to be realised; a tragic drama, but how often acted! — "Characters," Chapter 12, "The Prisoners' Van," p. 129.

Commentary

By coincidence, in 1876, the same year that he illustrated the Household Edition of Sketches by Boz Fred Barnard displayed the greatest of his large-scale canvasses at the Royal Academy, Saturday Night in the East End, in which he comments on appalling urban social conditions. The reviewer for The Academy on 27 May 1876 pronounced this large-scale painting as amongst "the most remarkable illustrations of London low-life [. . .] full of grime and flare, and of human uncouthness" (518). This half-page illustration shares that dynamic, underscoring Barnard's social conscience as sees the older prostitute's bravado as courageous, even as she confronts the police officer to the left and shields her younger sister (right) from the prying eyes of the crowd. Although Barnard individualises the onlookers, only the man in the paper hat, perhaps a plasterer or painter, stands out, as if it is he who initiates the dialogue with Emily, rather than merely picks up the banter later. Emily (centre) is the only figure we see clearly, and she is the focal point of everyone else's gaze, including that of the exploited children, the chimney-sweeps in the foreground, left. This is the social realism of the working classes, rather than the casual entertainments of the rising middle classes that have absorbed so much of Boz's attention heretofore. But, then, this observer was not originally "Boz," but a specialist in reporting on such issues as crime and prostitution.

Since George Hogarth, editor of the Evening Chronicle and Dickens's father-in-law, probably advised Dickens against using the pen-name "Boz" (associated with his sketches in the Morning and Evening Chronicle) for his contributions to Bell's, Dickens whimsically decided to use the name of the henpecked husband "Tibbs" in "The Boarding-house" and its sequel in the Monthly Magazine for the observant, witty, and forthright reporter of the dozen pieces that appeared in Bell's Life in London and Sporting Chronicle. This was a remarkable weekly periodical so popular that it had 24,000 regular readers (more than the readership of any other weekly or daily paper). Whereas the landlady's husband, little Tibbs, is a pathetically incompetent and "melancholy specimen of the story-teller" who never seems to get much beyond the opening of one his volunteer home-guard anecdotes from thirty years earlier,

The twelve sketches and stories Dickens publishes in Bell's between 27 September [1835] and 17 January [1836] are anything but 'melancholy specimens' of course. They include several comic tales of misplaced self-confidence and punctured pretentiousness, rather like the Monthly ones. However, they are mostly set rather lower down the social scale than those and in inner-city localities like 'the most secluded portion of Camden Town', or 'the populous and improving neighbourhood of Gray's-inn-lane', rather than in the suburbs. Also, they teem with sharply individualised vignettes of a greater variety of lower and lower-middle class Londoners (brilliant thumbnail sketches abound) as opposed to the stock farce types that tend to predominate in the earlier tales.

In one sketch, 'The Prisoners' Van' (Bell's Life, 29 Nov.), Dickens for the first time talks to his readers (in a relaxed and confident tone) about how he works and where he finds his material of choice, a passage omitted when the sketch was reprinted in the first volume of Sketches:

We have a most extraordinary partiality for lounging about the streets. Whenever we have an hour to spare, there is nothing that we enjoy more than a little amateur vagrancy — walking up one street and down another, and staring into shop windows, and gazing about us as if, instead of being on intimate terms with every shop and house in Holborn, the Strand, Fleet-street and Cheapside, the whole were an unknown region to our wondering mind. We revel in a crowd of any kind — a street 'row' is our delight . . . .

There follows a wonderfully vivid mini-sketch of a fatuous street row, of a somewhat milder kind than the all-female brawl featured in his first Tibbs sketch, 'Seven Dials' (Bell's Life, 27 Sept. [1835]). Then, having softened up his readers with this comic reportage, Dickens goes on to depict a disturbing scene of two girls, a brazen sixteen-year-old prostitute and her as yet unhardened younger sister, being carted off to Coldbath Fields (the Middlesex House of Correction). He challenges his readers, some of whom, certainly, would have occasionally been clients of such girls, to deny that this is a common scene. . . . — Michael Slater, "'The Copperfield Days': 1828-1835," p. 53.

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens: A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Bentley, Nicholas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens: Index. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z. The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1846.

Dickens, Charles. "The Prisoners' Van," Chapter 12 in "Characters," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1839; rpt., 1890. Pp. 202-204.

Dickens, Charles. "The Prisoners' Van," Chapter 12 in "Characters," Christmas Books and Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: James R. Osgood, 1875 [rpt. of 1867 Ticknor & Fields edition]. Pp. 376-77.

Dickens, Charles. "The Prisoners' Van," Chapter 12 in "Characters," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876. Pp. 128-29.

Dickens, Charles. "The Prisoners' Van," Chapter 12 in "Characters," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 1. Pp. 259-62.

Hawksley, Lucinda Dickens. Chapter 3, "Sketches by Boz." Dickens Bicentenary 1812-2012: Charles Dickens. San Rafael, California: Insight, 2011. Pp. 12-15.

Schlicke, Paul. "Sketches by Boz." Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1999. Pp. 530-535.

Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens: A Life Defined by Writing. New Haven and London: Yale U. P., 2009.

Last modified 18 May 2017