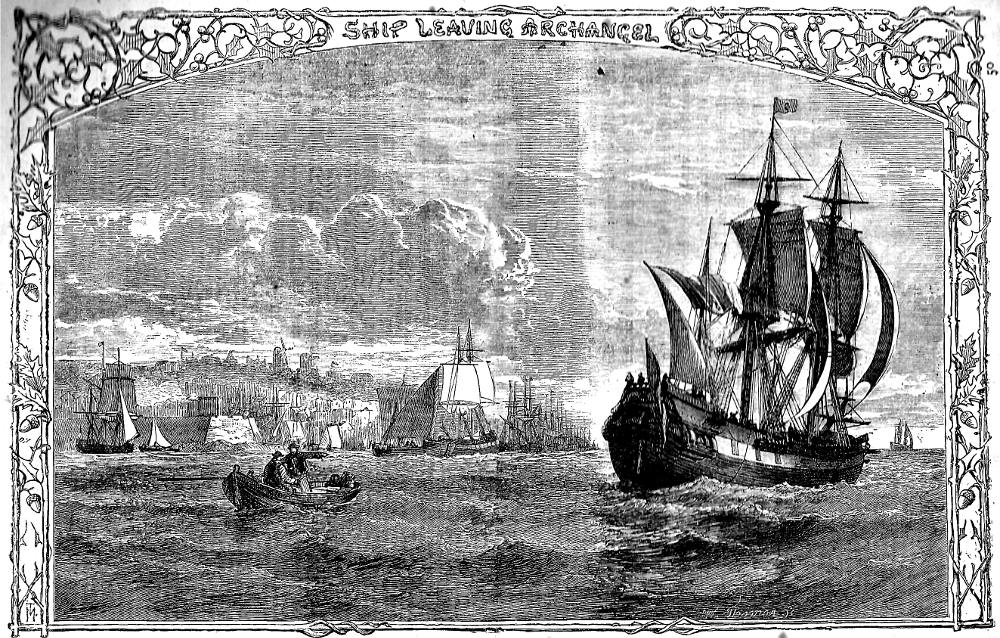

Ship leaving Archangel (page 393) — the volume's hundred-and-second composite wood-block engraving for Defoe's The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner. Related by himself (London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1863-64). Part II, The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, Chapter XVI, "Arrived Safe in England." Full-page, framed. 14 cm high x 21.7 cm wide. Running head: "Robbers in the Wood" (p. 391).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated: Crusoe departs for Home

In five days more we came to Veussima, upon the river Witzogda, and running into the Dwina: we were there, very happily, near the end of our travels by land, that river being navigable, in seven days’ passage, to Archangel. From hence we came to Lawremskoy, the 3rd of July; and providing ourselves with two luggage boats, and a barge for our own convenience, we embarked the 7th, and arrived all safe at Archangel the 18th; having been a year, five months, and three days on the journey, including our stay of about eight months at Tobolski.

We were obliged to stay at this place six weeks for the arrival of the ships, and must have tarried longer, had not a Hamburgher come in above a month sooner than any of the English ships; when, after some consideration that the city of Hamburgh might happen to be as good a market for our goods as London, we all took freight with him; and, having put our goods on board, it was most natural for me to put my steward on board to take care of them; by which means my young lord had a sufficient opportunity to conceal himself, never coming on shore again all the time we stayed there; and this he did that he might not be seen in the city, where some of the Moscow merchants would certainly have seen and discovered him.

We then set sail from Archangel the 20th of August, the same year; and, after no extraordinary bad voyage, arrived safe in the Elbe the 18th of September. Here my partner and I found a very good sale for our goods, as well those of China as the sables, &c., of Siberia: and, dividing the produce, my share amounted to £3475, 17s 3d., including about six hundred pounds’ worth of diamonds, which I purchased at Bengal. [Chapter XVI, "Arrived Safe in England," page 394]

Commentary: Crusoe in the Harbour of Archangel

The city spreads for over 40 kilometers (25 mi) along the banks of the river and numerous islands of its delta. Arkhangelsk was the chief seaport of medieval and early modern Russia until 1703. ["Arkhangelsk,"Wikipedia]

When Defoe wrote the novel, the new port and state shipyard at Archangel (named after the Archangel Michael), which Czar Peter the Great had commissioned in 1693, had recently opened as the home-base for the Russian ships Svyatoye Prorochestvo (Holy Prophecy), Apostol Pavel (The Apostle Paul), and the yacht Svyatoy Pyotr (Saint Peter). However, the progressive Czar realized that Arkhangelsk would always be limited as a result of the sea-ice which locked in the port for five months each year. Consequently, in May 1703, after waging war with the Swedes in the Baltic, he founded St. Petersburg as the Russian Empire's principal, year-round port.

However, to the Arctic port Archangel at the end of the seventeenth century Crusoe and his business partner make their way with a shipment of sables and Chinese silks for the Western European market. From the mid-sixteenth century, the chief Western European vessels in the harbour every summer were Dutch and English, although it was chiefly the former who traded in this area. In spite of its remote location on the Arctic coast and its wintry climate, Archangel retained its position as Russia’s most vital trading port until well into the eighteenth century. As Crusoe's narration implies, Archangel was originally situated several miles inland, up the Northern Dvina River, near the White Sea, rather than actually on the ocean, as the 1864 illustration suggests.

Its history as an English port-of-call began in the middle of the sixteenth century:

Three English ships set out to find the Northeast passage to China in 1553; two disappeared, and one ended up in the White Sea, eventually coming across the area of Arkhangelsk. Ivan the Terrible found out about this, and brokered a trade agreement with the ship's captain, Richard Chancellor. Trade privileges were granted to English merchants in 1555, leading to the founding of the Company of Merchant Adventurers, which began sending ships annually into the estuary of the Northern Dvina. Dutch merchants also started bringing their ships into the White Sea from the 1560s. Scottish and English merchants also traded in the 16th century; however, by the 17th century it was mainly the Dutch that sailed to the White Sea area. ["Arkhangelsk: Trade with England, Scotland, and the Netherlands," Wikipedia]

The Cassell illustration, featuring a busy port with windmills on the hill, is probably as fanciful as The Port of Archangel by Flemish seascape-painter Bonaventura Peeters the Elder (23 July 1614–25 July 1652). Presumably the two figures being rowed away from the Hamburg-bound vessel are not Crusoe and his business partner since they have already boarded the vessel in full sail departing the harbour.

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

References

"Arkhangelsk." Wikipedia. Accessed 16 April 2018. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arkhangelsk

"Arkhangelsk: Trade with England, Scotland, and the Netherlands." Wikipedia. Accessed 16 April 2018. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arkhangelsk#Early_history

Bonaventura Peeters the Elder. "The Port of Archangel." The Nation Maritime Museum, Greenwich. Accessed 16 April 2018. http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/13429.html#JvtFiRYGumDCstLB.99

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner. Related by himself. With upwards of One Hundred Illustrations. London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1863-64.

Last modified 17 April 2018