IN writing an introduction to this volume compiled by Mr. B. W. Matz and illustrated by Mr. Harold Copping, I am uncertain if I should attempt a criticism of Mr. Copping's clever work, which is far too well known to need an introduction, or whether I should allude in any way to the manner the book is presented to the artistic and literary world; nothing has been said to me on the subject, and I am generously left to my own devices and may write as I will.

Taking advantage, therefore, of my freedom in this respect, and taking also into consideration how the drawings and the book itself appeal to my sense of what is fitting and beautiful, I trust I may not be wrong in omitting all criticism, and in expressing merely a few words of sincere appreciation concerning what must surely give delight to thousands of my father's readers.

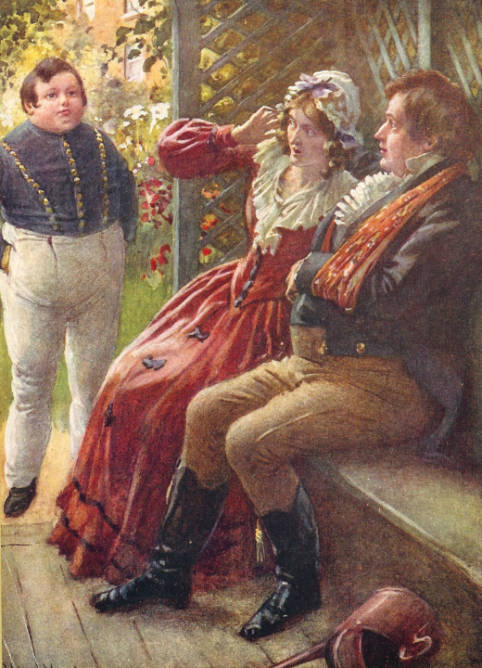

It is true that most of us have very definite views with regard to the appearance and bearing of every character to whom we are introduced in my father's novels, and it may happen sometimes these views (which are, of course, invariably the right ones) will vary ever so slightly from those held by Mr. Copping, on which rare occasions it were well if we agreed to differ, as Mr. Copping's ideas are always happy, and very often breathe the very spirit of the familiar figures and well remembered scenes they represent. As to the charming way his illustrations are reproduced and given to the public, the book speaks for itself and requires no interpreter. [7/8]

It may not be out of place if I mention here that, in answer to a request lately made, I have just heard from Mr. B. W. Matz, the well-known Editor of The Dickensian, who is more learned, I believe, in artistic and literary matters connected with my father than anyone else I know. He tells me no fewer than sixty artists resident in England and sixteen American artists have illustrated his works, and probably the number is still increasing, so tempting are his subjects to publisher and artist alike.

From The Pickwick Papers to The Mystery of Edwin Drood is a long journey. From the light-hearted though thrilling adventures of Mr. Pickwick and his followers to the mysterious gloom and evil doings of Jasper in the dear and dull old city of Cloisterham are many milestones, pointing to the names of Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickleby, The Old Curiosity Shop, Barnaby Rudge, Martin Chuzzlewit, Dombey and Son, David Copperfield, Bleak House, Hard Times, Little Dorrit, A Tale of Two Cities, Great Expectations, and Our Mutual Friend, besides those half-mile or quarter-mile stones, as they might be called, on which are engraved A Christmas Carol, The Chimes, The Cricket on the Hearth, The Battle of Life, The Haunted Man, and a host of articles, papers and shorter stories which appeared in Household Words and All the Year Round.

All these have been carefully noted and studied by Mr. Copping, and as we linger over some of the results of his meditations, our minds turn, as they have often turned before' to the man whose years were marked by such landmarks, which, like those on the Dover road, are self-evident, standing as they do in this case as the memorials of a busy life indeed; for my father was most certainly the 'strenuous worker " he has been constantly described by those authors who have made him the subject of their memoirs.

Yet there was nothing aggressively industrious in his manner of working, or in the quiet way he seemed to achieve more than many who made a greater parade of what they did. He was not " faddy " nor over particular in his choice of a study; indeed, during the years he lived at Gad's Hill he changed his writing room three times.[8/9] He seldom, if ever, volunteered any statement or information regarding his work unless directly called upon to do so, and I have known him leave it in the middle of a sentence, and without protest, if a slight domestic difficulty of any kind hurried him into acting as judge or adviser. Writing appeared as natural to him as breathing, and was so much the expression of his being and so satisfying to the intense restlessness of his nature, which for ever craved expression, as to make it doubtful whether, had that excitement been withdrawn, he could possibly have attained the comparatively early age at which he died. No one, however, enjoyed a holiday more than he, and no one could "laze " with more satisfaction to himself and others, but only for a short time. His real happiness throughout life consisted, I am convinced, in following the destinies of those imaginary people, who were scarcely imaginary to him, in the same way as he has caused them to seem living to his readers, through the light of his sympathy and understanding. To those of us who looked in upon him sometimes as he sat at his desk, with an eager expression of interest and enjoyment on his sensitive face, the swift conviction would come that here, if anywhere, was the right man in the right place, doing what was his, by right of an enormous capacity for the work before him.

This does not mean there were not hours, sombre hours, when he strove and nothing came of all his labour — hours when he called upon the invisible friends of his enchanted life and not one, perhaps, would answer to his call; sad hours of dulness, when he grew miserably depressed because he could not cover even one of the little blue "slips " on which he wrote and pondered; his poor tired brain refusing absolutely the work that lay before it.

My father's habit was to retire to his study after breakfast, and there remain until one-thirty, hard at work, or, if he had a bad day, waiting as cheerfully as he could for something to "turn up," in the true Micawber spirit: one of the chief and most significant unlikenesses between himself and the real Micawber being that something usually did turn up for the son, though never for the father.[9/10] On more fortunate mornings he enjoyed what in romantic Victorian days would have been called by elderly ladies " a flow of inspiration," an expression which did not in the least tally with my father's rather severe teaching that constant application and an honest determination bent on improving any small talent inherent in the individual were the only secrets of success, and without those plodding virtues, the much envied, often discussed, mysterious fairy-like gift men call "genius " would remain always but a beautiful wasted thing, incapable of doing any permanent good in the world, and as fleeting and unsubstantial as the pretty white butterflies hovering over the flower beds in the garden.

My father's vivid imagination, fancy and love of romance and mystery were curiously at variance with—if they may not be called the compensating qualities of&mash;his strong practical common-sense, the healthy sanity and vigour of his mind and his orderly precision and desire of accounting for whatever struck him as strange in himself or others. In early life, and warned by certain faults in the character of the father he dearly loved, he laid down a few wise rules for the guidance of his own conduct, which for many, many years of his life, I believe, he never departed from. He was hard upon himself in his self-training, although l have every reason for supposing this hardness was not extended to those friends who failed where he succeeded. He has often been called a self-made man, and perhaps was so in more ways than one, for in striving after qualities he felt he lacked in his neglected youth, he became possessed of some not originally his, and moulding these to his compelling will, they became as much part of himself as those more engaging and lovable characteristics born with him, for which he was loved and honoured.

"No gift of the mind, however great, however promising," he would say, "can ever compensate for the want of energy and patient attention in every-day work, and if these are present then everything is possible." This theory, advanced for the encouragement of his children, no doubt, has its weak side, for I fear not all the patient attention or energy the world holds can give the eye that [10/11] sees or the brain that understands; possibly, some such doubt passed through the minds of his young people as they listened to his exhortations, although they never breathed to one another any revolutionary sentiment on the subject, or allowed themselves to doubt for one moment that from the height of his own standards and the knowledge he possessed of things and human nature he was not absolutely right. Perhaps, in the curiously receptive, silent way children have of learning what they have not been taught, they realized completely the difference between their own thoughts and the imaginings of their father as shown in his stories, and knew that not to them, and maybe to none other for many years to come, would be given that which they recognized as beautiful and rare, even though they seldom heard it called in their own home by the high-sounding title of " genius"; the word seemed to them of small account, however, for the substance of it lay in the books they loved and devoured.

And what delights are to be found in those books, apart from the characterization and interest of the stories. What delights and constant change from town to country for the reader who can forget, if he wishes, dingy houses and crowded streets, and, wandering away with a little girl and her grandfather, will come presently upon a kindly schoolmaster living in a green, secluded village; or, tired of rough winds blowing upon him from the Yarmouth sea, can take shelter with Bob Cratchit and his family in a London home, and share their Christmas dinner.

Much have been said and written on the subject of my father's pathos, and some have praised and others blamed it; but of the greater gift of humour which was his above all other gifts, and which in his case included so much that was pathetic and even tragic, who shall say enough of what it has done for those who have studied his works and turned to them for comfort in moments of depression and weariness? In Pickwick, the most frankly humorous of his books, his own youthful high spirits did not allow of his dwelling for long on sorrow of any kind, though here, in old [11/12] Mr. Weller's description of the death of his wife which he gives to his son Sam, is a curious foreshadowing of my father's combined humour and pathos which is very beautiful indeed, and which to many of us strikes a truer note than is to be found in his more hackneyed scenes of sentiment and long drawn-out distress. And this radiant gift of humour never deserted him, but remained spontaneously fresh and refreshing until his death, vindicating by its immortal presence the word he was so chary of using.

Related Material

- Biographical Note on Harold Copping (1863-1932): Illustrator of Dickens's Child Characters and the Bible

- "Foreword" by B. W. Matz

Bibliography

Dickens, Mary Angela, Percy Fitzgerald, Captain Edric Vredenburg, and Others. Illustrated by Harold Copping with eleven coloured lithographs. Children's Stories from Dickens. London: Raphael Tuck, 1893.

Dickens, Mary Angela [Charles Dickens' grand-daughter]. Dickens' Dream Children. London, Paris, New York: Raphael Tuck & Sons, Ltd., 1924.

Matz, B. W., and Kate Perugini; illustrated by Harold Copping. Character Sketches from Dickens. London: Raphael Tuck, 1924. Copy in the Paterson Library, Lakehead University.

Created 15 February 2009 Last updated 13 October 2023