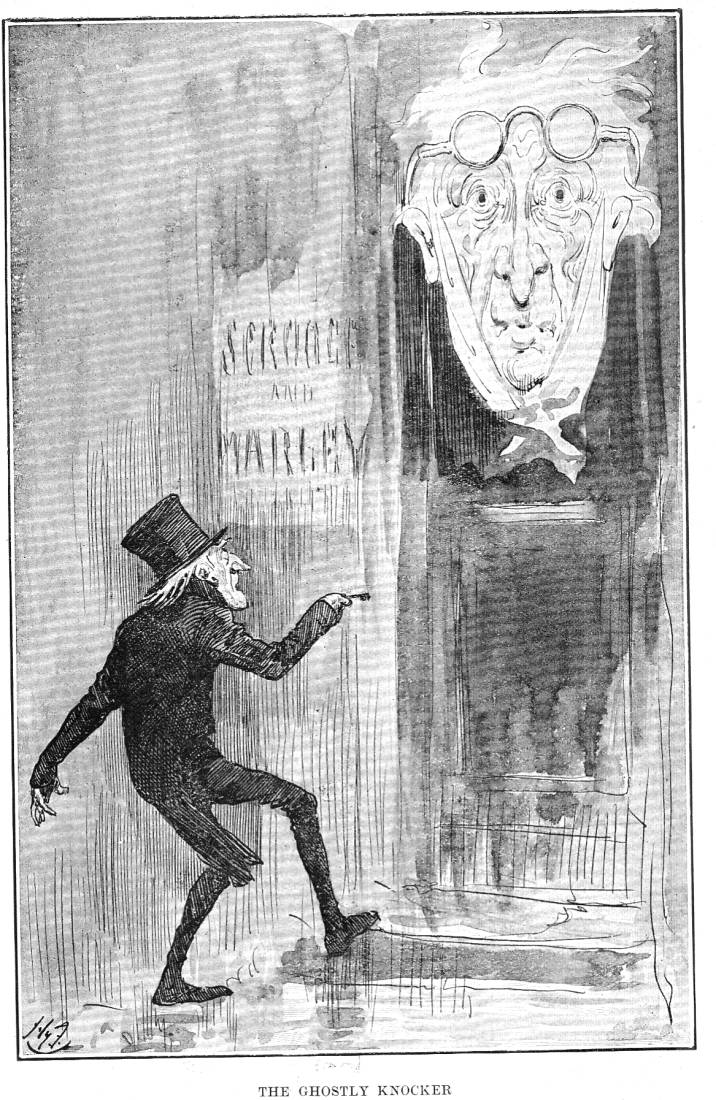

The Ghostly Knocker

Harry Furniss

1910

14.5 by 9.3 cm (5 ¾ by 3 ⅝ inches), framed.

Fourth lithographic illustration for A Christmas Carol in The Christmas Books, Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910), Vol. VIII, facing page 17.

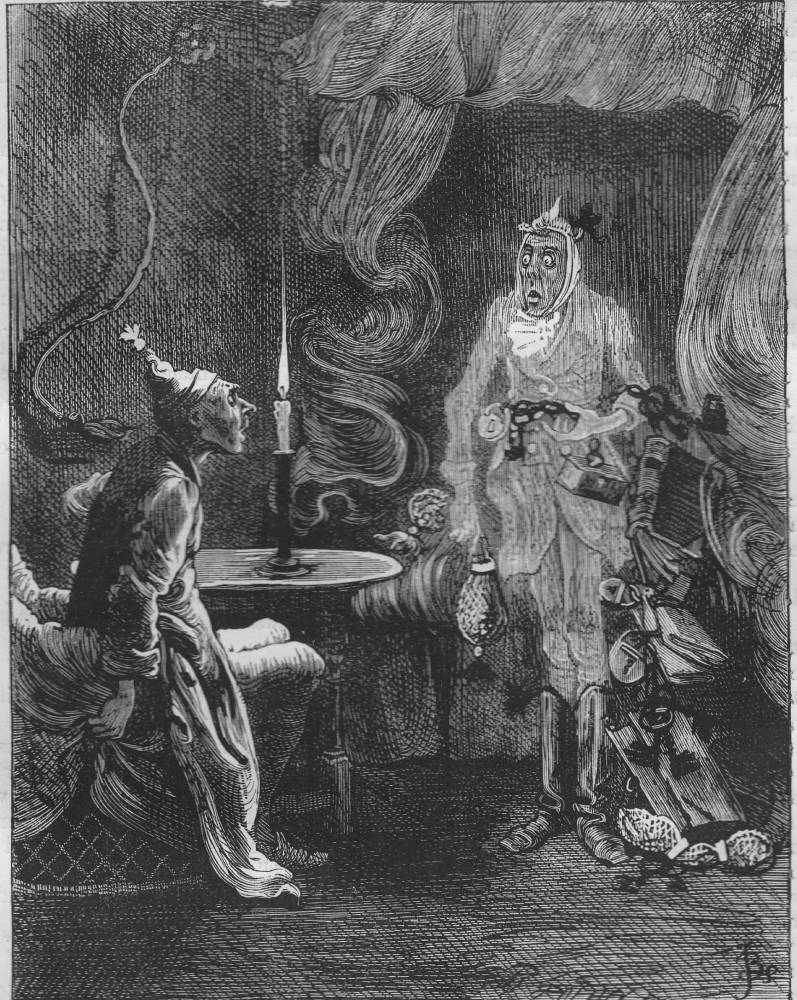

In the image of a diminutive Scrooge and a gigantic door-Knocker with the face of Jacob Marley — complete with chin-wrapping and glasses on The forehead, immediately suggesting both the corpse and the living partner whom Scrooge knew so well — Furniss offers simultaneously psychological insight and whimsical caricature. [Commentary continued below.]

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use the images on this page without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Realised: The Knocker's Transformation

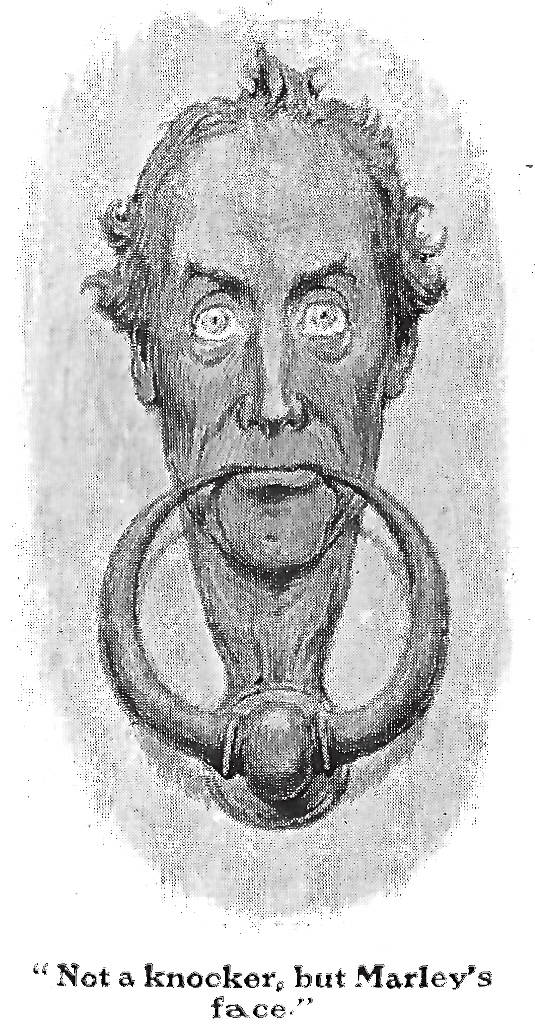

Now, it is a fact, that there was nothing at all particular about the knocker on the door, except that it was very large. It is also a fact, that Scrooge had seen it, night and morning, during his whole residence in that place; also that Scrooge had as little of what is called fancy about him as any man in the city of London, even including — which is a bold word — the corporation, aldermen, and livery. Let it also be borne in mind that Scrooge had not bestowed one thought on Marley, since his last mention of his seven years' dead partner that afternoon. And then let any man explain to me, if he can, how it happened that Scrooge, having his key in the lock of the door, saw in the knocker, without its undergoing any intermediate process of change — not a knocker, but Marley's face.

Marley's face. It was not in impenetrable shadow as the other objects in the yard were, but had a dismal light about it, like a bad lobster in a dark cellar. It was not angry or ferocious, but looked at Scrooge as Marley used to look: with ghostly spectacles turned up on its ghostly forehead. The hair was curiously stirred, as if by breath or hot air; and, though the eyes were wide open, they were perfectly motionless. That, and its livid colour, made it horrible; but its horror seemed to be in spite of the face and beyond its control, rather than a part or its own expression.

As Scrooge looked fixedly at this phenomenon, it was a knocker again. [Stave One, "Marley's Ghost," p. 11]

Commentary

The door is oversized, intimidating, and the knocker's face "seems to be expanding like a genie released from a bottle" [Davis 121 & 126]. The knocker as a psychological manifestation need have no real-life point of origin, but T. W. Tyrell in "The 'Marley' Knocker" in the Dickensian (October 1924) has suggested that Dickens's transformation of bronze door-knocker into Marley's face was influenced by an unusual knocker with a man's face (as opposed to the usual lion's head) "that hung on the front door of No. 8 Craven Street when it was occupied by one Dr. David Rees in the 1840s" (cited in Guiliano and Collins, I: 841, and Hearn, Note 55, p. 70].

In style, the illustration looks like a washed water-colour, the only background detail discernible being the bronze nameplate to the left of the portal. Furniss permits nothing to detract from Scrooge's wonder at the massive head that has appeared just as he is about to place his key in the lock. The gigantic head, perhaps suggestive of spiritual enlightenment, is a ghostly white, in contrast to Scrooge's black hat and business-suit.

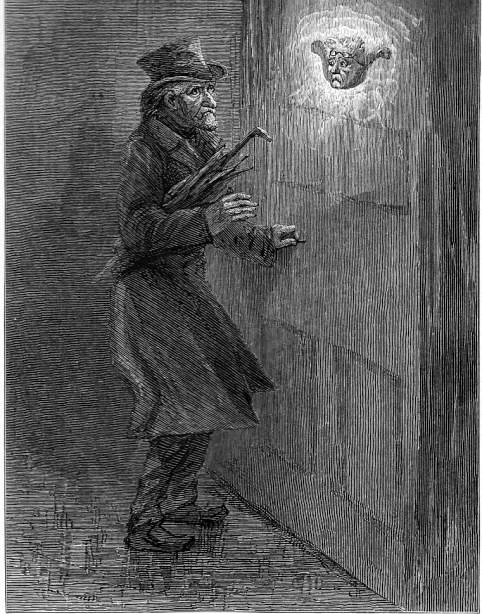

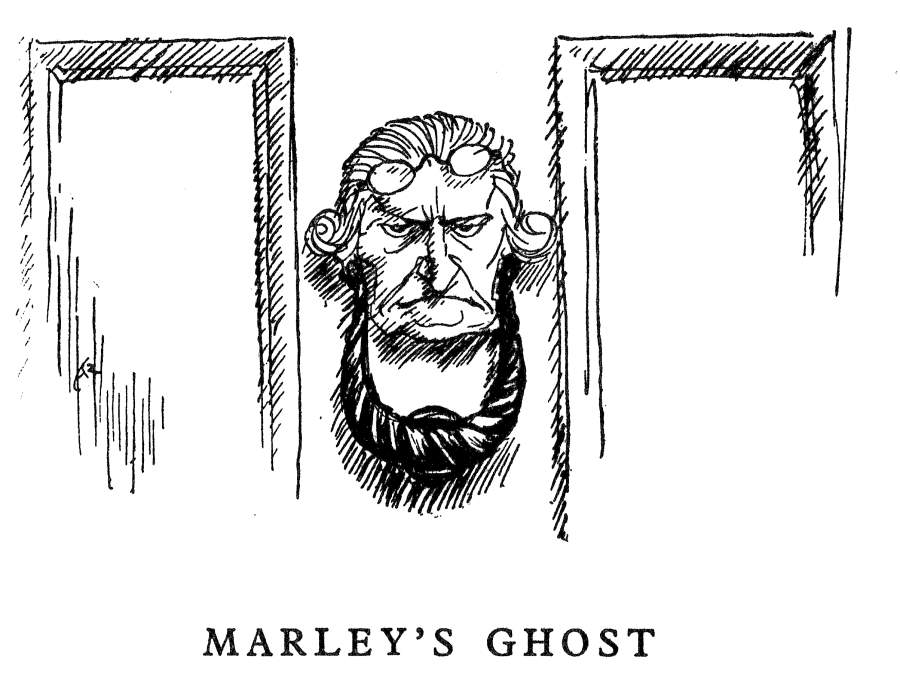

John Leech in the original edition focussed not on this prelimiary warning of Marley's arrival from the depths of Scrooge's subconscious and the grave, but rather on the arrival of the chain-dragging spirit himnself several pages later. Sol Eytinge, Junior, in his twenty-fifth anniversary Carol seems to have been the first illustrator to consider the transformation scene as worthy of pictorial comment; certainly it is important in that it marks the point at which Scrooge departs from strict reality into a world of vivid memories and terrifying nightmares. Few artists have had the opportunity to provide such a realisation, the other exception to this observation being Arthur Rackham in his 1915 tour de force. Both of the Household Edition illustrators, having the space for only a few illustrations, like Leech have chosen to show Scrooge's reaction to the Ghost's arrival as Scrooge sits, trying to get comfortable in front of a weak fire after the disturbing initial visitation. Neither Eytinge's realistic treatment, with Scrooge in a topcoat and carrying an umbrella, nor Rackham's study of the door-knocker itself in a simple pen-and-ink drawing, captures the psychological dimension of Scrooge's confrontation with the metaphysical world — and neither possesses Furniss's humour.

It may be that these Victorian illustrators realised the limitations of the media with which they had to work — copper-plate and steel engraving, wood-engraving, photogravure, and lithograph — in depicting one image becoming another. This sort of transformative effect was most easily achieved in the nineteenth century in the medium of the magic lantern show, whereby an image could appear to change as another glass slide was superimposed upon an initial version of the image. An accomplished magic lantern speaker who knew the potentialities of the medium, Furniss was likely aware also of the possibility of achieving such a transformation with film. However, the problem that his "Ghostly Knocker" exhibits in the print medium is that the image must either be the face (as in his illustration) or a knocker with a small-scale human head (as in Eytinge's 1868 wood-engraving).

Only in such film adaptations as Noel Langley's screenplay for Brian Desmond Hurst's Renown Rank production in 1951 of A Christmas Carol (otherwise, Scrooge), starring Alastair Sim, can the moment be suitably frightening; the reader finds it difficult, in contrast, to take either the 1868 or the 1915 illustration seriously. Indeed, Furniss, himself a film pioneer from 1912 with Thomas Edison in New York (Cordery 1, 5), must have come to appreciate how the new medium of silent, black-and-white film could accomplish the desired effect since he would likely have seen the 1913 Scrooge produced by Hepworth in England (cited in Bolton 243). Perhaps having seen a specimen of the new medium (Cordery and Bolton note that the first cinematic adaptation of Dickens goes back to 1897), Rackham decided to avoid making much of the transformation scene, for he downplays the moment by simply showing a disgruntled Marley as the knocker, and does not attempt to capture the transformation — or Scrooge's reaction to it.

Related Illustrations from Other Editions (1878 to 1915)

Left: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s "Marley's Face" (1868). Right: Arthur Rackham's "Heading to Stave One" (1915). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Left: Charles Green's closeup study Scrooge's Knocker (1912), featuring a psychologically magnified version of the knocker. Right: Fred Barnard's Marley's Ghost (1878) depicts the miser's second encounter with his dead partner's spirit.

Bibliography

Bolton, Philip. Dickens Dramatized. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1987.

Cordery, Gareth. An Edwardian's View of Dickens & His Illustrators: Harry Furniss's "A Sketch of Boz." Greensboro, NC: University of North Carolina Press and ELT Press, 2005.

Davis, Paul. The Lives and Times of Ebenezer Scrooge. New Haven: Yale U. P., 1990.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books, illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Junior. Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867. Vol. X.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books, illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878. Vol. XVIII.

_____. Christmas Books, illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. VIII.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman and Hall, 1843.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose. Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1868.

Guiliano, Edward, and Philip Collins, eds. The Annotated Dickens. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1986. Vol. 1.

Hearn, Michael Patrick, ed. The Annotated Christmas Carol. New York: Avenel, 1976.

Tyrell, T. W. "The 'Marley' Knocker." The Dickensian (October 1924).

Victorian

Web

Visual

Arts

Illustration

Harry

Furniss

Next

Last modified 4 June 2013

Last modified 6 January 2026