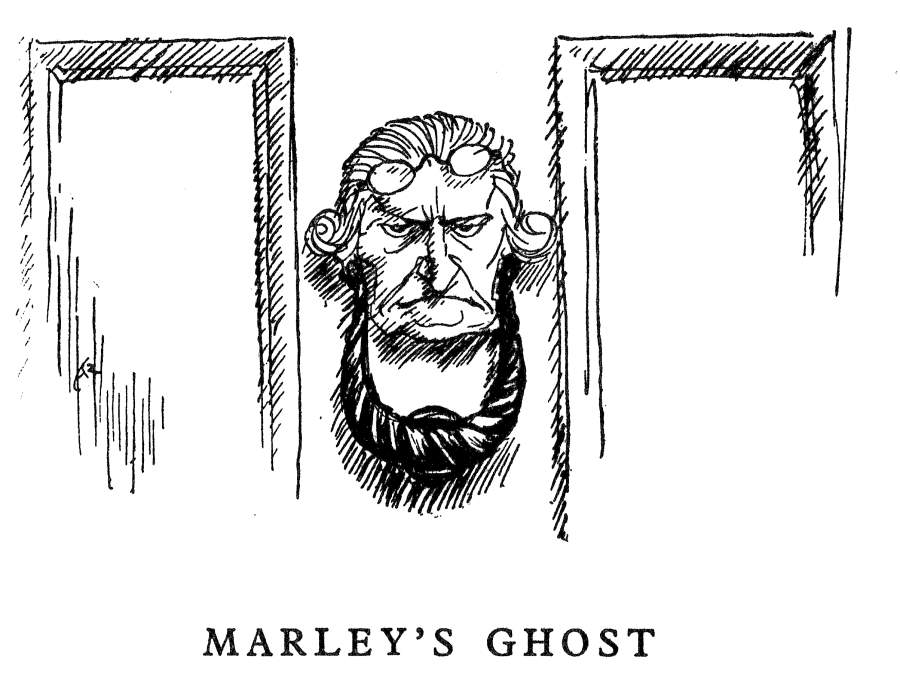

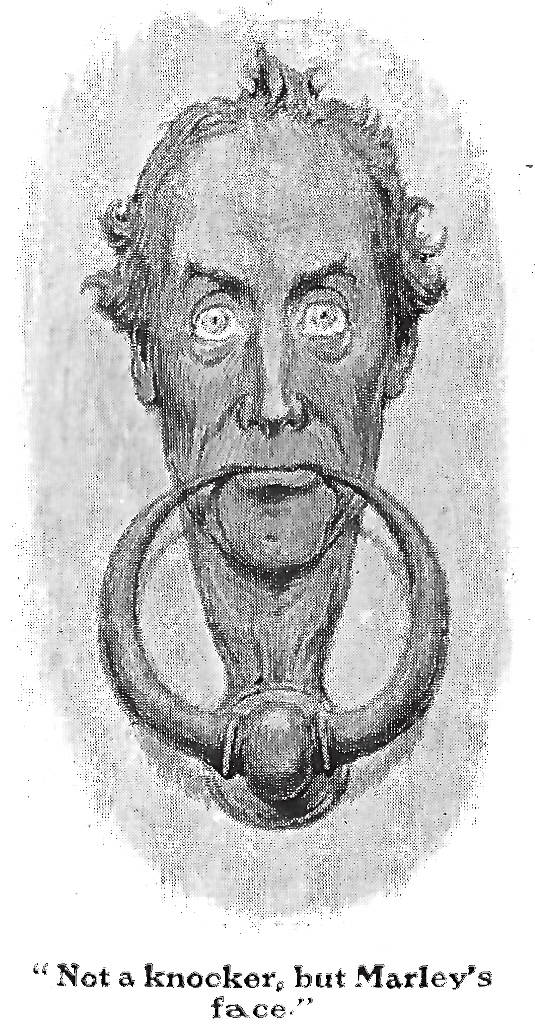

Marley's Ghost by Arthur Rackham. 1915. Photographic reproduction of pen-and-ink drawing. Illustration for Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, page 13. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Commentary: The Initial Transformation

Arthur Rackham’s headpiece for "Marley's Ghost” marks that magical moment when Ebenezer Scrooge crosses from the real, prosaic world of business and his spartan existence into the supernatural world of ghosts, spirits, visions, and visitations. As he reaches for the handle on his front door, he seems to hear his old partner's voice, calling his name out of the fog and darkness of Christmas Eve, momentarily disorienting the usually unflappable miser:

Scrooge, having his key in the lock of the door, saw in the knocker, without its undergoing any intermediate process of change — not a knocker, but Marley’s face.

Marley’s face. It was not in impenetrable shadow as the other objects in the yard were, but had a dismal light about it, like a bad lobster in a dark cellar. It was not angry or ferocious, but looked at Scrooge as Marley used to look: with ghostly spectacles turned up on its ghostly forehead. The hair was curiously stirred, as if by breath or hot air; and, though the eyes were wide open, they were perfectly motionless. That, and its livid colour, made it horrible; but its horror seemed to be in spite of the face and beyond its control, rather than a part of its own expression.

As Scrooge looked fixedly at this phenomenon, it was a knocker again. [Stave I, "Marley's Ghost," pp. 24-26]

When, his wanderings in the company of the three Spirits of Christmas finally over, Scrooge reprises the moments around his dwelling associated with his supernatural visitors, he notes first his front-door, now forever transformed into a portal into a new life: “There’s the door, by which the Ghost of Jacob Marley entered!" (Stave V, "The End of It," page 134)

Scrooge sees Marley in death as he saw him in life, with his spectacles above his forehead, implying that he is near-sighted. And, indeed, his mind never went far from the "money-changing hole" (33) of Scrooge & Marley.

The American illustrator who had just met Charles Dickens in person in 1867, Sol Eytinge, Junior, in his twenty-fifth anniversary Christmas Carol, seems to have been the first illustrator to consider the transformation of the knocker as worthy of pictorial comment; certainly it is important in that it marks the point at which Scrooge departs from strict reality through a metaphysical portal into a world of vivid memories and terrifying nightmares. Few artists have had the opportunity to provide such a realisation, the other exception to this observation being Arthur Rackham in his 1915 tour de force. The knocker of the story, as Arthur Rackham may have known, was inspired by an actual door-knocker that Charles Dickens saw in the vicinity of Cornhill. The knocker as envisaged by Rackham is neither psychologically magnified nor animated, but resembles the actual door-knocker that Dickens had in mind and described, a knocker with a man's face rather than (as was usual) a lion's. It was the door-knocker on a house in eighteenth-century Craven Street that gave the writer the idea for one of the most memorable scenes in all of his work. T. W. Tyrell in "The 'Marley' Knocker" in the Dickensian (October 1924) has suggested that Dickens's transformation of bronze door-knocker into Marley's face was influenced by an unusual knocker with a man's face "that hung on the front door of No. 8 Craven Street when it was occupied by one Dr. David Rees in the 1840s" (cited in Guiliano and Collins, I: 841, and Hearn, Note 55, p. 70]. However, the unwanted attention the door received in the twentieth century has resulted in the owner's having it taken down and placed in a bank vault. However, least we have the residue of this memorable object constantly before us in the many illustrated editions of the Carol. Rackham's long-haired Marley gazes upon the reader as he does upon Scrooge with a slightly sour expression, as if resenting the fact that callers pound the back of his head onto a brass plate!

Relevant Illustrations from the 1843, 1868, 1910, and 1912 Editions

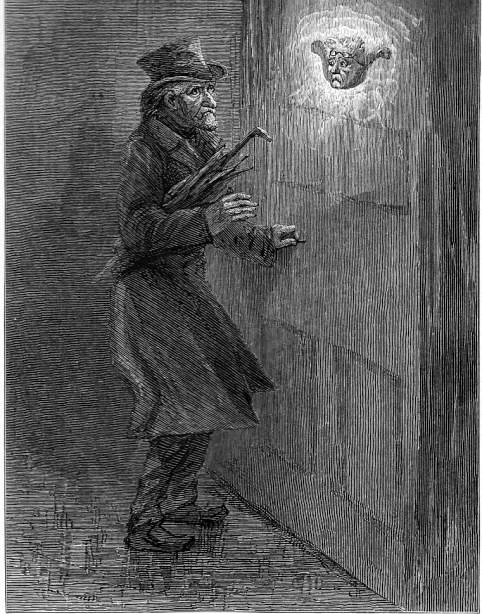

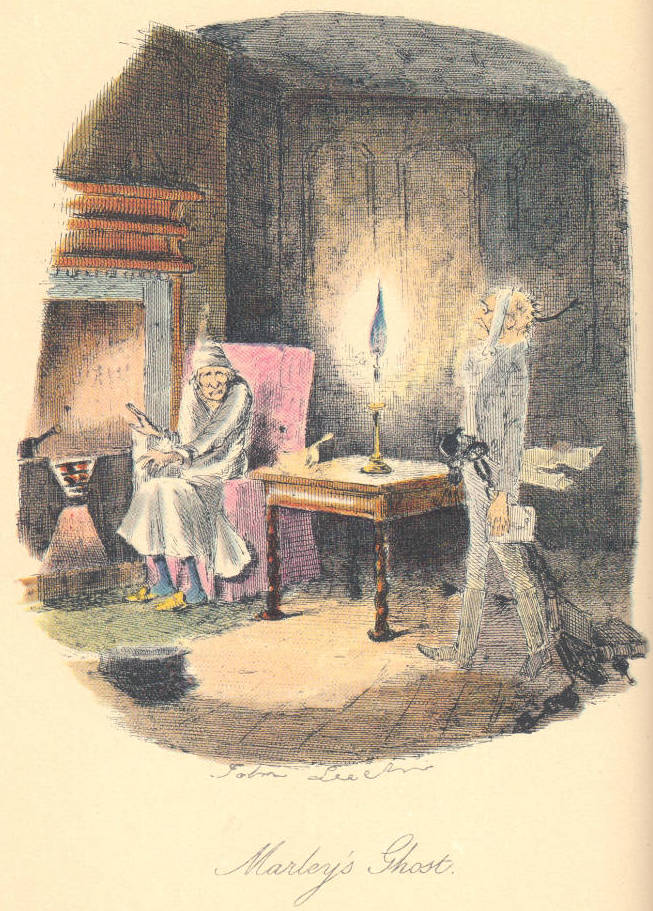

Left: Sol Eytinge, Junior's scene of Scrooge's shock at seeing Old Marley's likeness on his own door, Marley's Face. Right: John Leech's interpretation of the arrival of the shade of Scrooge's former partner, Marley's Ghost.]

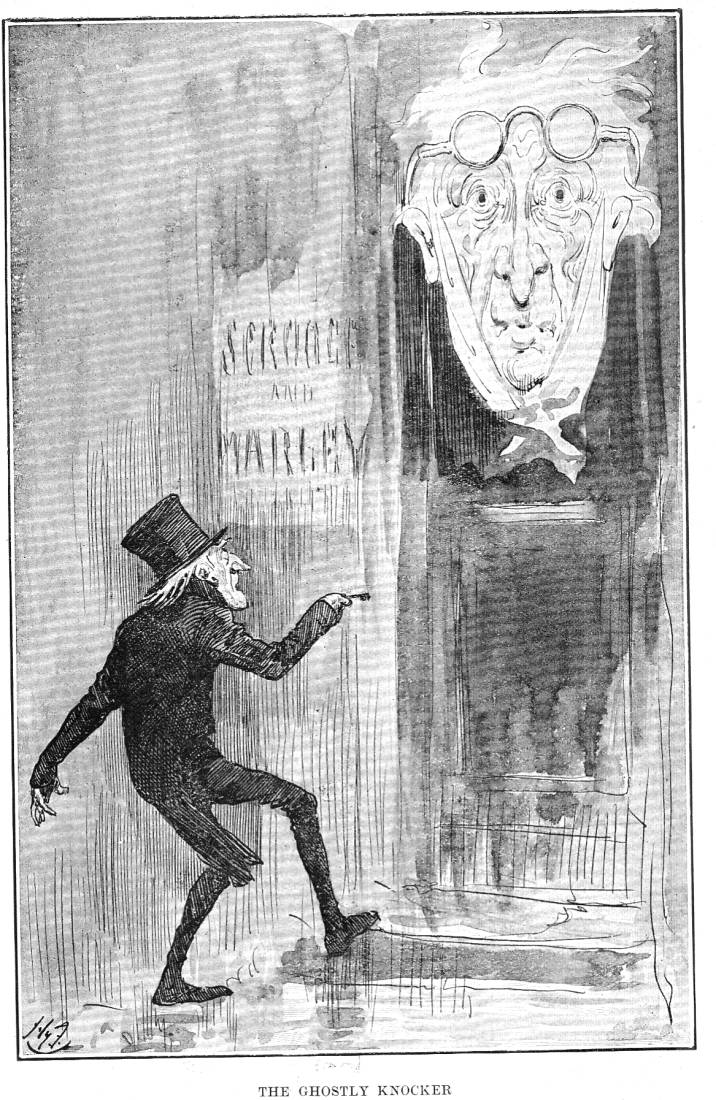

Left: Harry Furniss's The Ghostly Knocker (1910), featuring a psychologically magnified version of the knocker. Right: Charles Green's lithograph of the dour-faced knocker, Not a knocker, but Marley's Face (c. 1912).

References

The Annotated Dickens. (Vols 1 & 2 containing Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist, A Christmas Carol, Hard Times, David Copperfield, A Tale of Two Cities, and Great Expectations.) Edited, with introduction and notes by Edward Guiliano and Philip Collins. London: Orbis Books, 1986.

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol in Prose: being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman & Hall, 1843.

____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1868.

____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Charles Green, R. I. London: A & F Pears, 1912.

____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Arthur Rackham. London: William Heinemann, 1915.

Hearne, Michael Patrick, ed. The Annotated Christmas Carol. New York: Avenel, 1989.

Last modified 26 June 2019