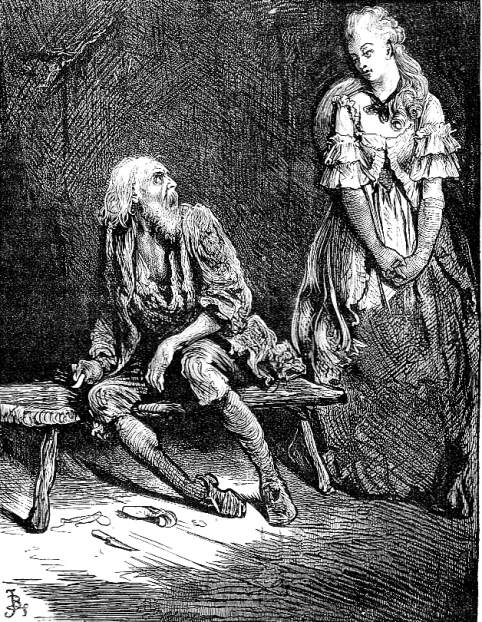

The Shoemaker of the Bastille by Harry Furniss. 1910. Vignetted, 9 cm high x 14 cm wide. Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, The Charles Dickens Library Edition, facing XIII, 49. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

When the quiet of the garret had been long undisturbed, and his heaving breast and shaken form had long yielded to the calm that must follow all storms — emblem to humanity, of the rest and silence into which the storm called Life must hush at last — they came forward to raise the father and daughter from the ground. He had gradually dropped to the floor, and lay there in a lethargy, worn out. She had nestled down with him, that his head might lie upon her arm; and her hair drooping over him curtained him from the light.

"If, without disturbing him," she said, raising her hand to Mr. Lorry as he stooped over them, after repeated blowings of his nose, "all could be arranged for our leaving Paris at once, so that, from the very door, he could be taken away —"

"But, consider. Is he fit for the journey?" asked Mr. Lorry.

"More fit for that, I think, than to remain in this city, so dreadful to him." [Book One, Chapter Six, "The Shoemaker," 42-43: the picture's original caption has been emphasized]

Commentary

In The Shoemaker of the Bastille Furniss has responded with a study in contrasts to Phiz's more stoic serial illustration The Shoemaker (June 1859: see below). Phiz had visualised with great sensitivity the reunion of father and daughter which Dickens first describes in the 2 May 1859 weekly instalment in All the Year Round. However, whereas in the original serial illustration and subsequent illustrations the dutiful daughter kneels before her long-lost father, in Furniss's more emotional interpretation of the same scene the ex-prisoner is prostrate, and his daughter acts as his nurse rather than as a child. Although Furniss uses the caption The Shoemaker of the Bastille to underscore Dr. Manette's loss of identity as a political prisoner in solitary confinement, he does not — like John McLenan in A white-haired man sat on a bench, stooping forward and very busy, making shoes — actually depict the quondam-physician as a shoemaker, for the bench (left rear) is barely recognizable as such in the vigorous pen-and-ink sketch. Furniss accentuates the differences between the tender young woman with luxuriant hair and the exhausted, bald old man, creating a sense of the sacred by rendering the garret (in the manner of Phiz in the original) as a sort of hermit's grotto, and by eliminating the dispassionate onlookers whom Phiz included in the 1859 steel engraving, Jarvis Lorry and Ernest Defarge.

Martin Meisel in Chapter 15 of Realizations, "Dickens' Roman Daughter," notes that the daughter's tending the prisoner-father is something of a pattern in Dickens's works, the locus classicus of which remains Little Dorrit's tending "The Father of the Marshalsea," which (Meisel notes) was Dickens's updated prose account of "the much-painted scene of 'Roman Charity'" (303), a painterly commonplace known in the Renaissance as Caritas Romana (305), the ultimate source of which was the classical writer Valerius Maximus. An example of the concept's realisation in the visual arts is Andrea Sirani's Roman Charity (1630-1642). This reversal of the nurturing parent-nurtured child relationship occurs more oddly in the Jenny Wren-Mr. Dolls household in Our Mutual Friend (1864-65). Furniss's image, then, is more consistent than most of the other illustrators' realisations with the "maternal daughter" concept in Dickens's text. Meisel describes the effects of the Roman Charity paintings that Dickens admired when he visited the various Italian city-states in the mid-1840s:

From the womb or grave of the Marshalsea he [William Dorrit] is resurrected, and his infancy and childhood are given him, by the child-woman who reverses time and Nature to redeem them.

Dickens did not purge himself of the prison theme, or outgrow the countervailing image of Roman Charity, with the conclusion of Little Dorrit. He came back to them in A Tale of Two Cities, whose imagination belongs to the period of renewed creativity immediately after his first Italian visit, and is hardly distinguishable from the germ of Little Dorrit.

The image of Roman Charity recurs in A Tale of Two Cities, in a section entitled "Recalled to Life." It takes form (like a tableau vivant) in a prepared fictive setting, designed to accommodate the actual world to the mental world of the prisoner. Dr. Manette, recently released from the Bastille but unable to accept his condition, is brought together with his daughter, Lucie, in a garret room that has been darkened and made into a pseudo-cell The wine-shop keeper, Defarge, ostentatiously wielding a key, stands in for the jailor. Lucie is required by her father's fragile mental state to restrain her "eagerness to lay the spectral face upon her warm young breast, and love it both to life and hope." But eventually she succeeds in taking him to her, and rocks him on her heart "like a child." The release comes, and the tableau configuration (including spectators) is completed, when she evokes Manette's tears for both the irremediable and irrecoverable past and the living present:

He had sunk in her arms, and his face dropped on her breast: a sight so touching, yet so terrible in the tremendous wrong and suffering which had gone before it, that the two beholders covered their faces. [TTC, I, vi]

Much else in A Tale of Two Cities recalls the imagery and concerns of Little Dorrit, but they are shifted, as here, to a bolder, broader key, appropriate to a drama played within the heroic framework of a historical action.

Note 26 [ 315] Letters, Pilgrim Edition, 4: 590. Dickens mentioned to Forster the convoluted "idea of a man imprisoned for ten or fifteen years, emphasizing his imprisonment being the gap between the people and circumstances of the first part and the altered people and circumstances of the second, and his own changed mind." Dickens then explored the psychology of the long-term prisoner, newly released, in old Dorrit, in Arthur Clennam returning from exile, and most sensationally in Mrs. Clennam making her nightmare journey through the unaccustomed streets. He pursues the theme in Dr. Manette. [Meisel, 315]

Whereas the Phiz illustration involves a sort of "play-within-the-play," with both actors (Lucie and the shoemaker, centre) and audience (Defarge and Lorry, left), as if Dickens is reconstituting King Lear's reunion with the faithful Cordelia, Furniss in Baroque fashion emphasizes the emotional aspect of this fateful meeting for Lucie, supporting her long-lost father's head in her lap as his legs sprawl out of the constricted space of his new "cell." Although the text makes plain the presence of the witnesses Defarge and Lorry, Furniss has elected to remove them from the scene in order to focus on Lucie's responses to this novel and life-changing situation.

Related Materials

- A Tale of Two Cities (1859) — the last Dickens's novel "Phiz" Illustrated

- Costume Notes on A Tale of Two Cities

- List of Plates by Phiz for the 1859 Monthly Instalments

- John McLenan's Illustrations for Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities (1859)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Diamond Edition Eight Illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities (1867)

- 25 Illustrations for Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities by Fred Barnard (1874)

- A. A. Dixon's Illustrations for the Collins Pocket Edition of A Tale of Two Cities (1905)

Relevant Illustrations from earlier editions, 1859, 1867, and 18745.

Above: Phiz's revolutionary couple constantly on the lookout for royalist spies and informers in The Wine-shop. (1859).

Left: John McLennan's periodical illustration of the reunion scene in the garret above the St. Antoine wine-shop, He took her hair into his hand again, and looked closely at it; Centre: Sol Eytinge, Junior's dual character study, Doctor Manette and His Daughter (1867). Right: Fred Barnard's "What is this?" (1874).

Bibliography

Barnard, Fred. A Series of Character Sketches from Charles Dickens [Series One: Alfred Jingle, Mrs. Gamp, Bill Sikes, Little Dorrit, Samuel Pickwick, and Sidney Carton]. London: Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co., 1880 [portfolio].

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. , 1988.

Bolton, H. Phili "A Tale of Two Cities." Dickens Dramatized. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1987, 395-412.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. A Tale of Two Cities. All the Year Round. 30 April through 26 November 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by John McLenan. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. 7 May through 3 December 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). London: Chapman and Hall, 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London: Collins, 1905.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities, American Notes, and Pictures from Italy. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 13.

Meisel, Martin. Realizations: Narrative, Pictorial, and Dramatic Arts in Nineteenth-Century England. Princeton: Princeton U. , 1983.

Created 4 November 2013

Last modified 7 January 2020