[I have transcribed the following article from the Hathi Trust Digital Library online version of The Dome and its excellent OCR text. The two illustrations by Gyles appear in the article. I have added the Beardsley that Yeats mentioned. — George P. Landow]

THE only two powers that trouble the deeps are religion and love, the others make a little trouble upon the surface. When I have written of literature in Ireland, I have had to write again and again about a company of Irish mystics, who have taught for some years a religious philosophy which has changed many ordinary people into ecstatics and visionaries. Young men, who were, I think, apprentices or clerks, have told me how they lay awake at night hearing miraculous music, or seeing forms that made the most beautiful painted or marble forms seem dead and shadowy. This philosophy has changed its symbolism from time to time, being now a little Christian, now very Indian, now altogether Celtic and mythological ; but it has never ceased to take a great part of its colour and character from one lofty imagination. I do not believe I could easily exaggerate the direct and indirect influences which “A. E." (Mr. George Russell), the most subtle and spiritual poet of his generation, and a visionary who may find room beside Swedenborg and Blake, has had in shaping to a definite conviction the vague spirituality of young Irish men and women of letters. I know that Miss Althea Gyles, in whose work I find so visionary a beauty, does not mind my saying that she lived long with this little company, who had once a kind of conventual house; and that she will not think I am taking from her originality when I say that the beautiful lithe figures of her art, quivering with a life half mortal tragedy, half immortal ecstasy, owe some thing of their inspiration to this little company. I indeed believe that I see in them a beginning of what may become a new manner in the arts of the modern world; for there are tides in the imagination of the world, and a motion in one or two minds may show a change of tide.

Pattern and rhythm are the road to open symbolism, and the arts have already become full of pattern and rhythm. Subject pictures no longer interest us, while pictures with patterns and rhythms of colour, like Mr. Whistler's, and drawings with patterns and rhythms of line, like Mr.Beardsley's in his middle period, interest us extremely. Mr. Whistler and Mr. Beardsley have sometimes thought so greatly of these patterns and rhythms, that the images of human life have faded almost perfectly; and yet we have not lost our interest. The arts have learned the denials, though they have not learned the fervours of the cloister. Men like Sir Edward Burne-Jones and Mr. Ricketts have been too full of the emotion and the pathos of life to let its images fade out of their work, but they have so little interest in the common thoughts and emotions of life, that their images of life have delicate and languid limbs that could lift no burdens, and souls vaguer than a sigh; while men like Mr. Degas, who are still interested in life, and life at its most vivid and vigorous, picture it with a cynicism that reminds one of what ecclesiastics have written in old Latin about women and about the world.

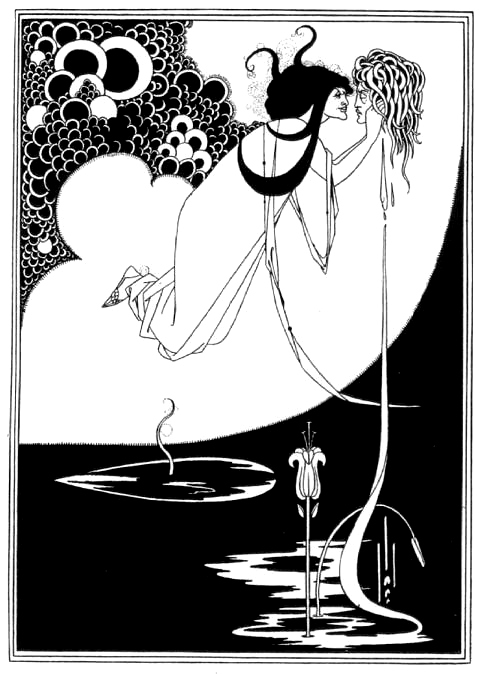

Once or twice an artist has been touched by a visionary energy amid his weariness and bitterness, but it has passed away. Mr. Beardsley created a visionary beauty in Salome with the Head of John the Baptist, but because, as he told me, “beauty is the most difficult of things,” he chose in its stead the satirical grotesques of his later period. If one imagine a flame burning in the air, and try to make one's mind dwell on it, that it may continue to burn, one's mind strays immediately to other images; but perhaps, if one believed that it was a divine flame, one's mind would not stray. I think that I would find this visionary beauty also in the work of some of the younger French artists, for I have a dim memory of a little statue in ebony and ivory. Certain recent French writers, like Villiers De L'Isle Adam, have it, and I cannot separate art and literature in this, for they have gone through the same change, though in different forms. I have certainly found it in the poetry of a young Irish Catholic who was meant for the priesthood, but broke down under the strain of what was to him a visionary ecstasy; in some plays by a new Irish writer; in the poetry of “A. E.”; in some stories of Miss Macleod's; and in the drawings of Miss Gyles; and in almost all these a passion for symbol has taken the place of the old interest in life. These persons are of very different degrees and qualities of power, but their work is always energetic, always the contrary of what is called “decadent.” One feels that they have not only left the smoke of human hearths and come to The Dry Tree, but that they have drunk from The Well at the World's End [a prose fantasy by William Morris].

Miss Gyles' images are so full of abundant and passionate life that they remind one of William Blake's cry, “Exuberance is Beauty,” and Samuel Palmer's command to the artist, “Always seek to make excess more abundantly excessive.” One finds in them what a friend, whose work has no other passion, calls “the passion for the impossible beauty"; for the beauty which cannot be seen with the bodily eyes, or pictured otherwise than by symbols. Her own favourite drawing, which unfortunately cannot be printed here, is The Rose of God, a personification of this beauty as a naked woman, whose hands are stretched against the clouds, as upon a cross, in the traditional attitude of the Bride, the symbol of the microcosm in the Kabala; while two winds, two destinies, the one full of white and the other full of red rose petals, personifying all purities and all passions, whirl about her and descend upon a fleet of ships and a walled city, personifying the wavering and the fixed powers, the masters of the world in the alchemical symbolism. Some imperfect but beautiful verses accompany the drawing, and describe her as for “living man's delight and his eternal revering when dead.”

I have described this drawing because one must understand Miss Gyles' central symbol, the Rose, before one can understand her dreamy and intricate Noah's Raven. The ark floats upon a grey sea under a grey sky, and the raven flutters above the sea. A sea nymph, whose slender swaying body drifting among the grey waters is a perfect symbol of a soul untouched by God or by passion, coils the fingers of one hand about his feet and offers him a ring, while her other hand holds a shining rose under the sea. Grotesque shapes of little fishes flit about the rose, and grotesque shapes of larger fishes swim hither and thither. Sea nymphs swim through the windows of a sunken town and reach towards the rose hands covered with rings; and a vague twilight hangs over all. The story is woven out of as many old symbols as if it were a mystical story in “The Prophetic Books.” The raven, who is, as I understand him, the desire and will of man, has come out of the ark, the personality of man, to find if the Rose is anywhere above the flood, which is here, as always, the flesh, “the flood of the five senses.” He has found it and is returning with it to the ark, that the soul of man may sink into the ideal and pass away; but the sea nymphs, the spirits of the senses, have bribed him with a ring taken from the treasures of the kings of the world, a ring that gives the mastery of the world, and he has given them the Rose. Henceforth man will seek for the ideal in the flesh, and the flesh will be full of illusive beauty, and the spiritual beauty will be far away.

The Knight upon the Grave of his Lady tells much of its meaning to the first glance; but when one has studied for a time, one discovers that there is a heart in the bulb of every hyacinth, to personify the awakening of the soul and of love out of the grave. It is now winter, and beyond the knight, who lies in the abandonment of his sorrow, the trees spread their leafless boughs against a grey winter sky; but spring will come, and the boughs will be covered with leaves, and the hyacinths will cover the ground with their blossoms, for the moral is not the moral of the Persian poet: “Here is a secret, do not tell it to any body. The hyacinth that blossomed yesterday is dead.” The very richness of the pattern of the armour, and of the boughs, and of the woven roots, and of the dry bones, seems to announce that beauty gathers the sorrows of man into her breast and gives them eternal peace.

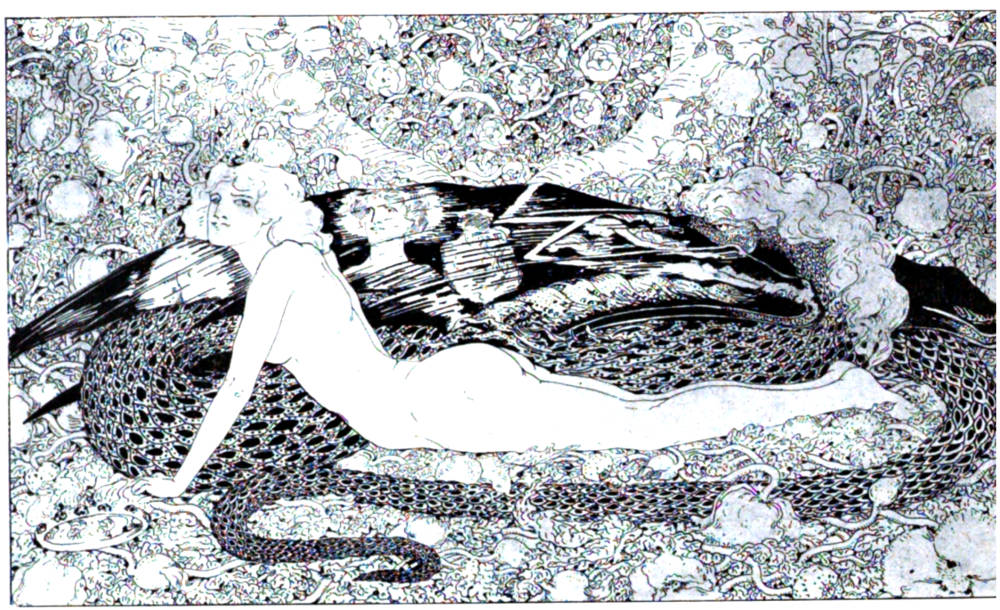

It is some time since I saw the original drawing of Lilith, and it has been decided to reproduce it in this number of The Dome too late for me to have a proof of the engraving; but I remember that Lilith, the ever-changing phantasy of passion, rooted neither in good nor evil, half crawls upon the ground, like a serpent before the great serpent of the world, her guardian and her shadow; and Miss Gyles reminds me that Adam, and things to come, are reflected on the wings of the serpent; and that beyond, a place shaped like a heart is full of thorns and roses. I remember thinking that the serpent was a little confused, and that the composition was a little lacking in rhythm, and upon the whole caring less for this drawing than for others, but it has an energy and a beauty of its own. I believe that the best of these drawings will live, and that if Miss Gyles were to draw nothing better, she would still have won a place among the few artists in black and white whose work is of the highest intensity. I believe, too, that her inspiration is a wave of a hidden tide that is flowing through many minds in many places, creating a new religious art and poetry.

W. B. Yeats.

Note.—The following are the legends for two of Miss Gyles' drawings, as chosen by herself —

DEIRDRE. “There is but one thing now may comfort my heart, and that thing thy sword, O Maisi.”

LILITH REGINA TRAGAEDLE. “O Lilith, tristissima, cujus in corde terrae prima magna tragaedia acta est, propter te adhue amoris manum tenet invidia.” (“O most sorrowful Lilith, in whose heart was played Earth's first great tragedy, still for thy sake does Hatred hold Love's hand.")

Bibliography

Yeats, W. B. “A Symbolic Artist and the Coming of Symbolic Art.” The Dome 1 (1898): 233-37. Hathi Trust Digital Library. Web. 30 October 2019.

Last modified 31 October 2019