rthur Hughes (1832-1915) is familiar to students of Victorian art as one of many painters of the mid-nineteenth century who worked in a Pre-Raphaelite style. Widely regarded as a quiet and unassuming character with limited ambition, Hughes was the author, nevertheless, of vivid works in watercolour and oil. In part a realist, with a keen eye for verisimilitude and the details of the real world, he was at the same time a poetic painter of saturated colours, idealized beauty, deep emotion and delicate states of mind.

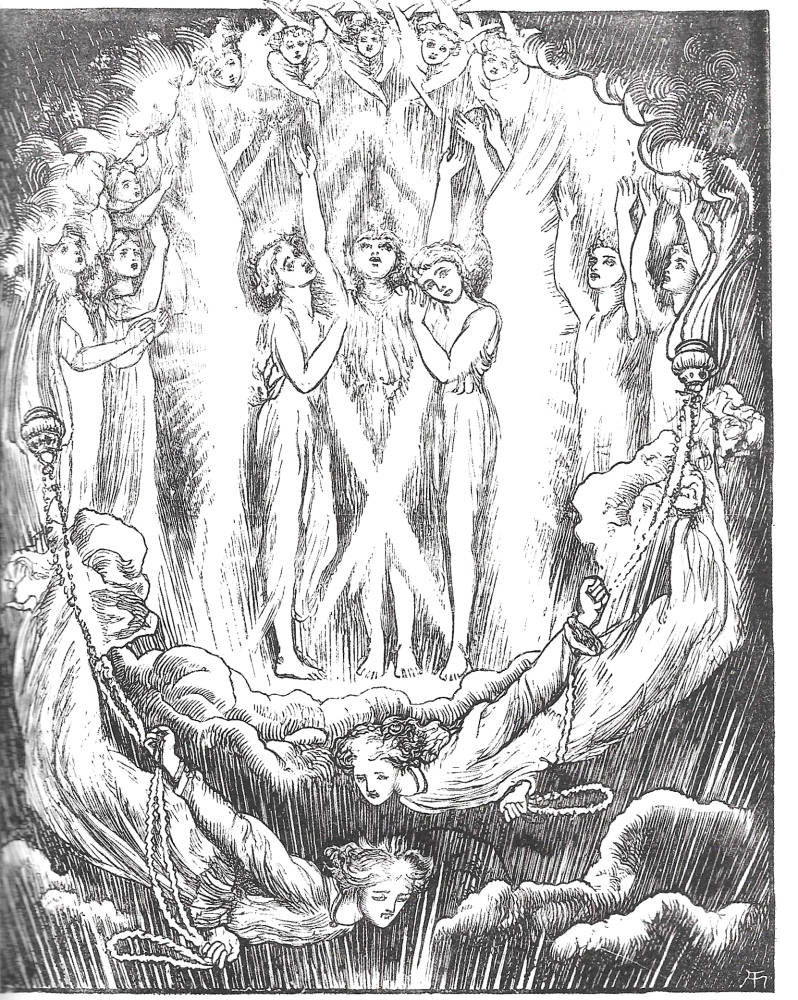

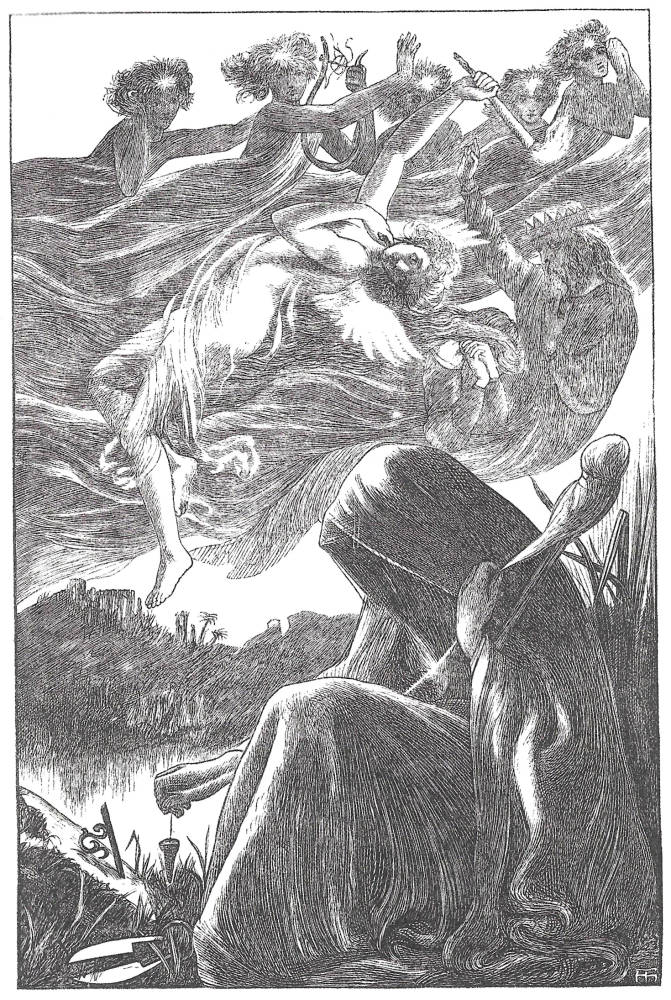

He was equally accomplished as a designer in black and white, extending his poetic vision into the small domain of wood-engraved illustrations for books and magazines. He was a major contributor to the so-called "golden age" of the 1860s, and he helped to define the idea of Pre-Raphaelite book-design. By turns contemporary, medievalist, religious, fantastical and often downright weird, his engravings for the page are curious, interior worlds which combine idealized beauties " especially androgynous men " with formal experiments in distortion, flattened space, manipulations of scale and the abstract beauties of pattern-making. These qualities made him a powerful interpreter of books for children and of subjects with a spiritual content. Glimpsed, as it were, in suspended animation, his figures seem to occupy an alternative world as signs within an iconography of angels, imps, grotesques, swooning maidens and swirling arabesques of Pre-Raphaelite hair.

The qualities of these illustrations have been analysed in several publications, notably those by Forrest Reid (1928), Paul Goldman (1996, 2004) and Gregory Suriano (2000), as well as in a number of critical essays; however, the first book-length monograph to consider this unusual artist’s work is Maroussia Oakley’s The Book and Periodical Illustrations of Arthur Hughes.

Two illustrations by Arthur Hughes. Left: The First Sunrise from The Sunday Magazine (February 1872). Right: Fancy from Good Words (November 1870). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Oakley’s study, a weighty 325 pages, is an encyclopaedic examination of Hughes’s oeuvre in this field. There are 184 reproductions of his illustrations. The range and complexity of the imagery is clearly displayed and for that alone the monograph constitutes a significant visual essay. However, Oakley’s focus is not on style but on the contexts in which the artist operated, notably his dealings with authors and publishers, but also with a number of others.

The opening chapter explores Hughes’s illustrations for poetry and traces in detail the working relationships that led to his visual interpretations of Tennyson’s Enoch Arden (1866), Christina Rossetti’s Sing Song (1870), and Thomas Hake’s Parables and Tales (1872). Previous criticism has shown how artists were engaged within a complex nexus in which personal contact was as important as artistic suitability, and Oakley demonstrates at length how Hughes’s commissions were influenced on all sides; operating within an industrial mode of production, his contacts were all-important. The circumstances surrounding the illustration of Enoch Arden are especially telling, and Oakley deftly charts the patterns of influence, favour and suggestion that cohered into an offer of work. "Why", she inquires, was Hughes chosen to illustrate the poem? (p.43). The answer is complicated, and was in part the result of his relationship with Thomas Woolner, the Pre-Raphaelite sculptor: “Hughes had painted Alice Woolner in 1865, and as Woolner was also a close friend of Tennyson, his influence might have helped to secure the commission for the Enoch Arden illustrations” (p.43).

The author goes on to note the involvement of J. Bertrand Payne, the new manager of Moxon’s and, it seems, an unhelpful participant in the process of securing the work:

Once the commission was agreed, Payne put pressure on Hughes to complete the drawings quickly. In early October 1865 an announcement was made about the forthcoming edition [and] on 9 October Woolner wrote to Emily Tennyson that he had heard from Hughes "who told me he had been working hard at "Enoch Arden" and that Payne had pressed him sharply as to time," but Woolner had advised Hughes "not to be pressed on any account so as to run any risk of doing the designs hastily" [p.43].

The situation is even more complicated in the case of Christina Rossetti’s Sing Song, which ultimately involved the publisher, the author, her siblings Dante Gabriel and William Michael, the Dalziel Brothers (who did the engraving), the publisher F. S. Ellis and " oh, yes, " the artist. These contacts, Oakley reveals, were essential in procuring the work, but they also put the artist under an immense amount of pressure, forcing him to accommodate competing and sometimes contradictory demands as a journeyman buffeted by the demands of economics, taste, personal influence, professional expediency, and sometimes " particularly in the case of individuals such as Dante Rossetti " by insiders" desire to meddle.

These fluid and dynamic situations are traced in the following chapters which explore Hughes’s book-work for children (Chapter 2), his diverse commissions for Alexander Strahan’s periodicals (3) and his illustrations in the period following on from the sixties and seventies. Most telling of all, in my view, is the chapter examining Hughes’s relationship with Alexander Strahan, the publisher of the evangelical Good Words and the same publisher’s Good Words for the Young. Building on her earlier essays in scholarly journals, Oakley navigates the many vicissitudes of Hughes’s work for this celebrated and demanding entrepreneur whose dealings were further enmeshed in the work of the Dalziels; authors such as Jean Ingelow and George Macdonald were on the scene and all of the participants" activities are placed within the economic context of the need to make money.

The book concludes with a chapter on "other work", an appendix considering reprints and other bibliographical matters, a complete bibliography of Hughes’s illustrations and an exhaustive listing of primary and secondary sources.

This thoroughness exemplifies Oakley’s meticulous research, which uncovers and co-ordinates a vast amount of contemporary documentation. Manuscript sources and printed accounts rarely been aired in modern studies are given a new and revealing prominence. The use of periodical reviews is particularly revealing, exposing a stratum of criticism which links the illustrations with the tastes of the readers for whom they were intended.

Oakley closes her study with a quotation from Laurence Housman, who notes how Hughes’s designs are infused with "beauty" and "charm", haunting the reader from first viewing in childhood to the days of the "older generation" (p.271). It is a lyrical conclusion to a thorough and interesting account, although the inclusion of Housman’s evaluative comment makes me wish that Oakley had ventured some more of her own; rigorously objective in her citations of other critics" opinions, I would have liked to have heard more of the author’s views on issues of style and aesthetics. For example, she explores Hughes’s first appearance in William Allingham’s The Music Master, but avoids making a judgement on his rookie’s performance, which is by all accounts pretty poor, especially in comparison with Rossetti’s contribution. It would have been interesting, in my view, to have noted how his entrée was so lacking in inspiration, but his later work so brilliant; his capacity to improve is surely worth investigation and I would have liked to have seen some analysis here.

Oakley’s book is nevertheless an invaluable investigation of a sometimes elusive figure. Written in lucid prose which is free from jargon or needless elaboration, it eloquently explains the relationships framing the artist’s production and significantly extends our understandings of the contexts of mid-Victorian book-design. An essential resource for scholars in the field and a more than adequate introduction for those discovering the subject for the first time, illustrated with high-quality scans and superbly designed by David Chambers, The Book and Periodical Illustrations of Arthur Hughes is a near-definitive study of Hughes’s graphic design.

Work Cited

Goldman, Paul. Victorian Illustration. Aldershot: Scolar, 1996; Lund Humphries, 2004.

Oakley, Maroussia. The Book and Periodical Illustrations of Arthur Hughes. Pinner: PLA & New Castle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press, 2016 [2017].

Reid, Forrest. Illustrators of the Sixties. London: Faber & Gwyer, 1928; rpt. New York: Dover, 1975.

Suriano, Gregory R. The Pre-Raphaelite Illustrators. London: The British Library & Delaware: Oak Knoll Press, 2000.

Last modified 14 February 2017