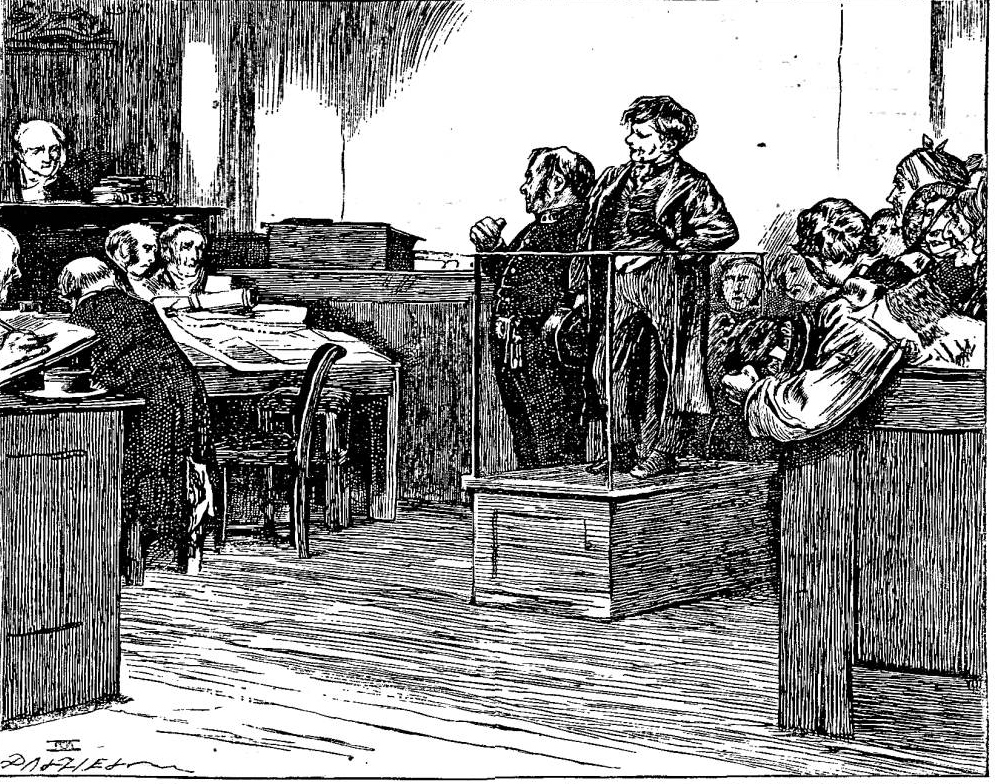

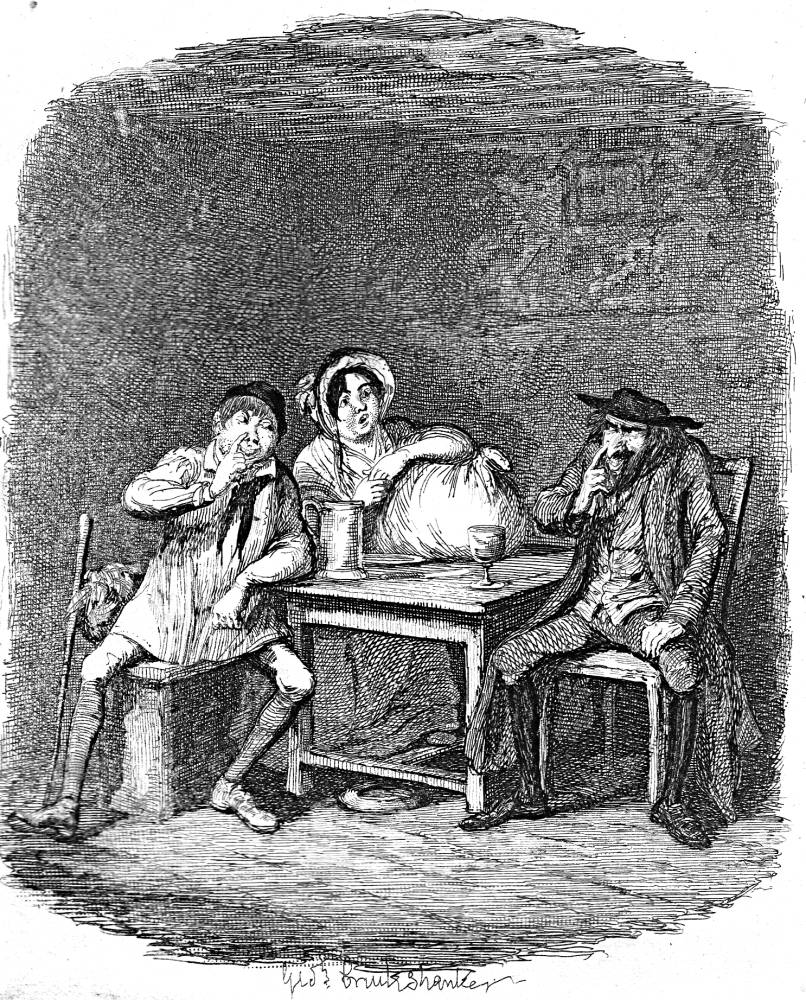

"What is this?" inquired one of the magistrates. — "A pick-pocketing case, Your Worship." — James Mahoney's wholly original illustration of the chirpy Cockney pickpocket casually challenging the authority of the magistrate's court as Noah Claypole, a new hire in the gang and therefore unknown to the police (disguised as a countryman in a linen smock-frock and holding a carter's whip) observes the proceedings on behalf of Fagin in Chapter 43 in the Household Edition. In the original narrative-pictorial serial sequence by George Cruikshank in Bentley's Miscellany, the periodical reader encountered instead Noah and Charlotte at The Three Cripples, sharing a beverage with the canny Fagin as he secures the services of "Morris Bolter" (otherwise, Noah Claypole) to steal coins on the "kinchin lay" (160, i. e., beating up children on errands) and to observe the Dodger's trial for theft of a snuff-box, a petty crime for which the Dodger will be transported to Botany Bay, New South Wales, Australia, in The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress in Part 19 (November 1838). The Mahoney illustration of the courtroom scene occurs on page 161 at the end of Chapter 42 and the beginning of Chapter 43, four pages before the textual passage in Chapter 43. 1871. Wood engraving by the Dalziels, 10.8 cm high by 13.7 cm wide.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.].

Passage Illustrated

It was indeed Mr. Dawkins, who, shuffling into the office with the big coat sleeves tucked up as usual, his left hand in his pocket, and his hat in his right hand, preceded the jailer, with a rolling gait altogether indescribable, and, taking his place in the dock, requested in an audible voice to know what he was placed in that 'ere disgraceful sitivation for.

"Hold your tongue, will you?" said the jailer.

"I'm an Englishman, ain't I?" rejoined the Dodger. "Where are my priwileges?"

"You'll get your privileges soon enough," retorted the jailer, "and pepper with 'em."

"We'll see wot the Secretary of State for the Home Affairs has got to say to the beaks, if I don't," replied Mr. Dawkins. "Now then! Wot is this here business? I shall thank the madg'strates to dispose of this here little affair, and not to keep me while they read the paper, for I've got an appointment with a genelman in the City, and as I'm a man of my word, and wery punctual in business matters, he'll go away if I ain't there to my time, and then pr'aps there won't be an action for damage against them as kep me away. Oh no, certainly not!"

At this point, the Dodger, with a show of being very particular with a view to proceedings to be had thereafter, desired the jailer to communicate "the names of them two files as was on the bench." Which so tickled the spectators, that they laughed almost as heartily as Master Bates could have done if he had heard the request.

"Silence there!" cried the jailer.

"What is this?" inquired one of the magistrates.

"A pick-pocketing case, your worship."

"Has the boy ever been here before?"

"He ought to have been, a many times," replied the jailer. "He has been pretty well everywhere else. I know him well, your worship."

"Oh! you know me, do you?" cried the Artful, making a note of the statement. "Wery good. That's a case of deformation of character, any way."

Here there was another laugh, and another cry of silence.

"Now then, where are the witnesses?" said the clerk.

"Ah! that's right," added the Dodger. "Where are they? I should like to see 'em."

[Chapter 43, "Wherein is shown how the Artful Dodger got into trouble," 165]

Commentary: Jack Dawkins, Transported Felon, and Other Dickensian Australians

To think of Jack Dawkins — lummy Jack — the Dodger — the Artful Dodger — going abroad for a common twopenny-halfpenny sneeze-box! I never thought he'd a done it under a gold watch, chain, and seals, at the lowest. Oh, why didn't he rob some rich old gentleman of all his walables, and go out as a gentleman, and not like a common prig, without no honour nor glory!" [Chapter 43, p. 163]

Although Fagin directs a string of street gypsies, the only two who stand out are the quick-witted pickpocket Jack Dawkins (otherwise, "The Artful Dodger," a sobriquet doubtless conferred by Fagin himself) and Charley Bates, far more benign and facetious figures than Fagin's chief criminal associate, the burglar Bill Sikes. After the trial of his boon companion in crime, the murder of Nancy, and the deaths of Bill Sikes and Fagin, Charley Bates reforms himself, "appalled by Sikes's crime," and, settling upon an agricultural life far removed from the Great Oven, eventually becomes "the merriest young grazier in all Northamptonshire." His partner in crime, the indefatigable Jack Dawkins, is tried for stealing a silver snuff-box, and in Chapter 43 is sentenced to criminal transportation, despite a vociferous and witty Cockney defense in which he tries to put the court itself on trial. For all his wit and "artfulness," Dawkins is sentenced to transportation for life to New South Wales, Britain's antipodean penal colony. Dickens later consigned Augustus Moddle in Martin Chuzzlwit to "Van Dieman's Land" (Tasmania), and the Micawbers, Martha Endell, and the Peggotty clan of David Copperfield to the Australian colony as sheep-farmers. Magwitch's fortune which supported Pip as a gentleman in Great Expectations is also derived from sheep ranching in New South Wales as, transported for life, Magwitch inherits his employer's estate. Transportation had ceased to be a sanction against British criminals in 1849, although many colonists in 1840 were under the impression that an Order in Council was sufficient to have revoked transportation, originally introduced as early as 1597 (to the Carolinas) and rejigged in 1788 (after the conclusion of the American Revolution) as an enlightened mode of relieving the crowding in British prisons. As Dawkins notes in the court, as part of Britain's penal system, transportation was in the portfolio of the Secretary of State for the Home Affairs. In the 1840s, Dickens in collaboration with heiress and humanitarian Angela Burdett-Coutts actively encouraged the reformed prostitutes of Urania Cottage to re-settle in Australia as productive daughters of empire who would marry prosperous ranchers, herders, and farmers. Two of Dickens's own sons (long after his writing Oliver Twist, Alfred in 1865 and Edward in 1868, having few prospects in England, took up sheep farming in the Outback, and Dickens had contemplated making a reading tour Down Under in 1862.

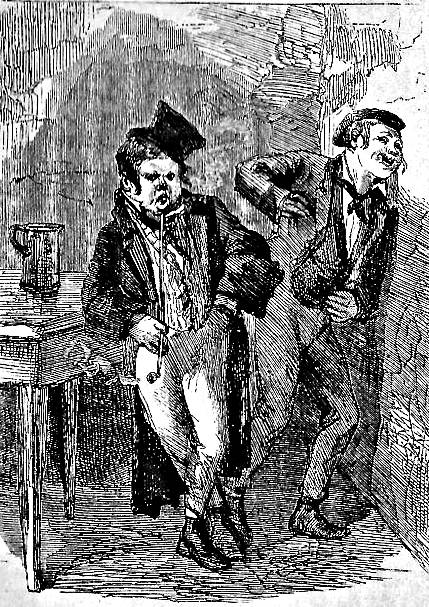

Mahoney's illustration focuses on the swaggering figure of The Dodger, looking for all the world like a miniature adult in coat and vest as he stands beside the uniformed jailer in the dock. The picture has the virtue of verisimilitude in terms of the juxtaposition of the various participants in the trial, including the public in the galleries (right), and the magistrate and court recorders (left). The conspicuous figure in the right foreground, his face turned away from the viewer and towards The Dodger, is undoubtedly Noah, identifiable by his linen smock-frock. Compare the clothing and face of the pickpocket here to Mahoney's handling of him in "What's become of the boy?". Although as self-confident and self-assured as The Dodgers of Mahoney and Eytinge, Furniss's youth seems to be a handsome, well-coiffed, fashionably dressed young adult rather than a pre-pubescent waif in cast-off adult clothing.

Illustrations from the serial edition (November 1838), Household Edition (1871), and Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

Left: George Cruikshank's serial engraving "The Jew & Morris Both begin to understand each other" (1838). Centre: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s "The Artful Dodger and Charley Bates" (1871). Right: Harry Furniss's Charles Dickens Library Edition illustration "The Artful Dodger before the Magistrates" (1910). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

References

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "George Cruikshank." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Letters of Charles Dickens. Ed. Graham Storey, Kathleen Tillotson, and Angus Eassone. The Pilgrim Edition. Oxford: Clarendon, 1965. Vol. 1 (1820-1839).

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1846.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Il. F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. Illustrated by James Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910.

Last modified 23December 2014