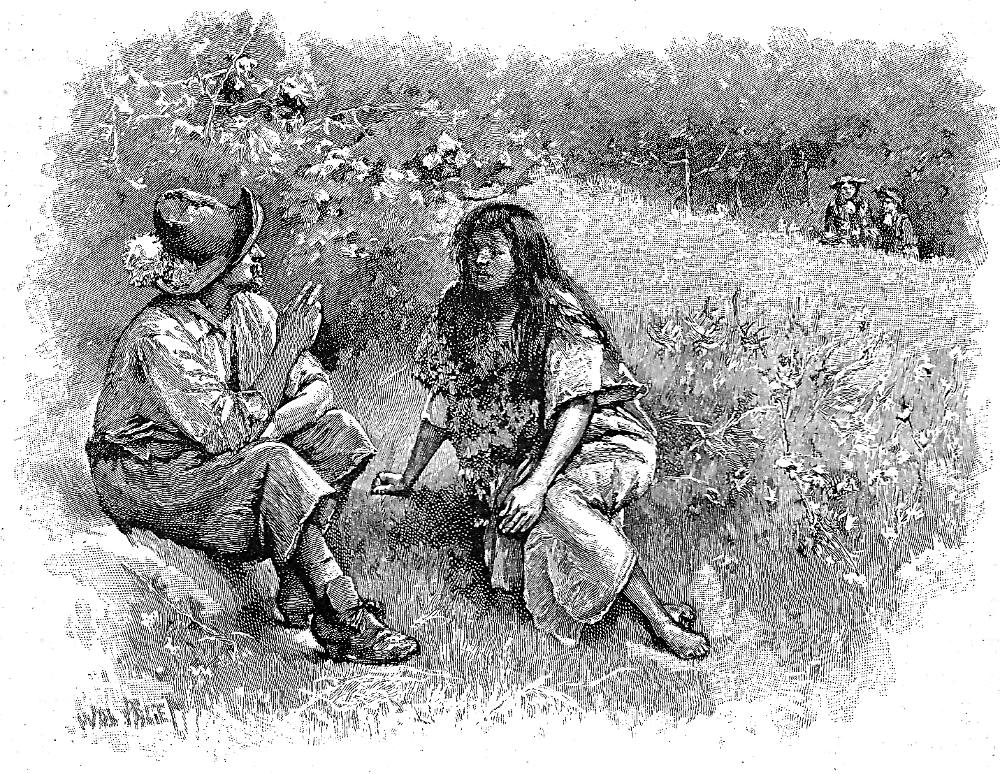

"Atkins and His Tawny Wife" (See p. 310), signed by Wal Paget, bottom left. Paget describes the conversation between European husband and aboriginal wife in far more casual terms than his precedessors George Cruikshank (1831) and William Luson Thomas (1864). Half of page 313, vignetted: 9 cm high by 11.6 cm wide. Running head: "Our Talk with Atkins" (page 313).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Text Illustrated: Atkins (of all people!) discusses Spiritual Matters

Upon this discourse, however, and their promising, as above, to endeavour to persuade their wives to embrace Christianity, he married the two other couple; but Will Atkins and his wife were not yet come in. After this, my clergyman, waiting a while, was curious to know where Atkins was gone, and turning to me, said, "I entreat you, sir, let us walk out of your labyrinth here and look; I daresay we shall find this poor man somewhere or other talking seriously to his wife, and teaching her already something of religion." I began to be of the same mind; so we went out together, and I carried him a way which none knew but myself, and where the trees were so very thick that it was not easy to see through the thicket of leaves, and far harder to see in than to see out: when, coming to the edge of the wood, I saw Atkins and his tawny wife sitting under the shade of a bush, very eager in discourse: I stopped short till my clergyman came up to me, and then having showed him where they were, we stood and looked very steadily at them a good while. We observed him very earnest with her, pointing up to the sun, and to every quarter of the heavens, and then down to the earth, then out to the sea, then to himself, then to her, to the woods, to the trees. "Now," says the clergyman, "you see my words are made good, the man preaches to her; mark him now, he is telling her that our God has made him, her, and the heavens, the earth, the sea, the woods, the trees, &c." — "I believe he is," said I. Immediately we perceived Will Atkins start upon his feet, fall down on his knees, and lift up both his hands. We supposed he said something, but we could not hear him; it was too far for that. He did not continue kneeling half a minute, but comes and sits down again by his wife, and talks to her again; we perceived then the woman very attentive, but whether she said anything to him we could not tell. While the poor fellow was upon his knees I could see the tears run plentifully down my clergyman’s cheeks, and I could hardly forbear myself; but it was a great affliction to us both that we were not near enough to hear anything that passed between them. Well, however, we could come no nearer for fear of disturbing them: so we resolved to see an end of this piece of still conversation, and it spoke loud enough to us without the help of voice. He sat down again, as I have said, close by her, and talked again earnestly to her, and two or three times we could see him embrace her most passionately; another time we saw him take out his handkerchief and wipe her eyes, and then kiss her again with a kind of transport very unusual; and after several of these things, we saw him on a sudden jump up again, and lend her his hand to help her up, when immediately leading her by the hand a step or two, they both kneeled down together, and continued so about two minutes. [Chapter VI, "The Clergyman's Counsel," pp. 310-11]

Commentary: Crusoe — Apostle of European Civilisation and Protestant Christianity

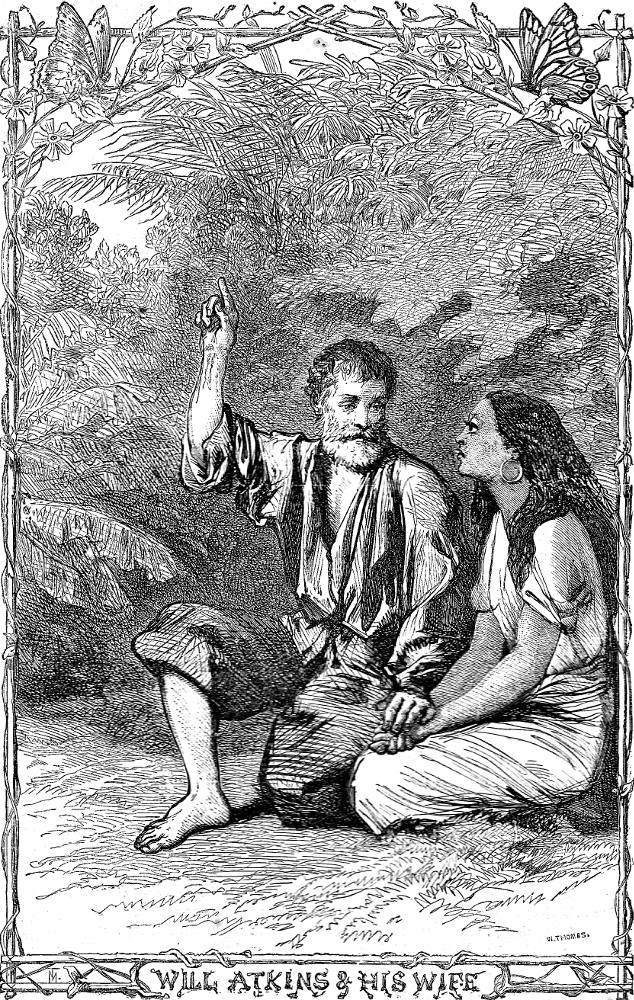

To the present-day reader Cassell's illustrator Wal Paget's choice of subject for the apostolic section of Crusoe's return to the island must seem, at first glance, decidedly odd — after all, Will Atkins, now casually gesturing heavenward, was the principal instigator of the mutiny at the end of Part One and has been a thorn in the side of the Spanish colonists thus far in Part two. However, the 1831 Cruikshank frontispiece for the second volume of the John Major edition as well as a full-page illustration in the 1864 Cassell edition provided precedents if not viable models for Paget's realistic portrayal of the reformed rowdyman. Although the Paget lithograph and the Cassell's wood-engraving are less clear than the equivalent Cruikshank steel-enbgraving about the setting, the scene is Will Atkins' plantation, one of three such plantations that Crusoe has visited upon his return to the island to gauge the progress of the colonists, not merely towards agricultural development and the acquisition of material wealth, but towards civilised thought. Thomas's and Paget's couples are much more credible than Cruikshank's immaculately dressed colonist and his willowy young wife; there is an informality about the pose and juxtaposition of Paget's Mr. and Mrs. Atkins that implies intimacy. They have not yet realised that Crusoe and his companion, the French clergyman, are about to interrupt their metaphysical conversation.

Since Atkins like the other colonists (both Spanish and English) has taken a native wife, Crusoe is delighted to learn that Atkins, formerly a ruffian, has embraced Christianity, and has even taken steps to educate his wife in the precepts of the Old Country's monotheistic religion. As a result, whatever children they have will be neither pagan nor agnostic, but English Christians — and dutiful children of Empire. Thomas, like Cruikshank before him, in choosing this particular scene for illustration in The Farther Adventures focuses, then, on Robinson Crusoe as a force for spiritual enlightenment rather than as a mere agent of European imperialism. Both the 1864 and the 1891 Cassell programs of illustration, in fact, focus on Crusoe's relationship with the French Catholic priest to dramatize the colonial founder's interest in seeing his "family" become thorough Christians, whether of the Catholic or Protestant persuasion — although he is quite insistent that Friday is a Protestant like himself.

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Parallel Scenes from Stothard (1790), Cruikshank (1831), and Cassell (1864)

Left: Thomas Stothard's study of Crusoe's distributing supplies to the colonists of both nationalities, Robinson Crusoe distributing tools of husbandry among the inhabitants. Centre: George Cruikshank's equivalent scene, Crusoe distributing agricultural implements. Right: William Luson Thomas's realisation of Atkins' discussion of religious matters in Will Atkins and his Wife (1864). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Above: Cruikshank's small-scale realisation of Crusoe's interest in spreading the words and spirit of the Gospel, Crusoe presents a Bible to Will Atkins and his native wife (1831). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

References

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner. Related by himself. With upwards of One Hundred Illustrations. London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1863-64.

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Exciting Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner, as Related by Himself. With 120 original illustrations by Walter Paget. London, Paris,and Melbourne: Cassell, 1891.

Last modified 1 April 2018