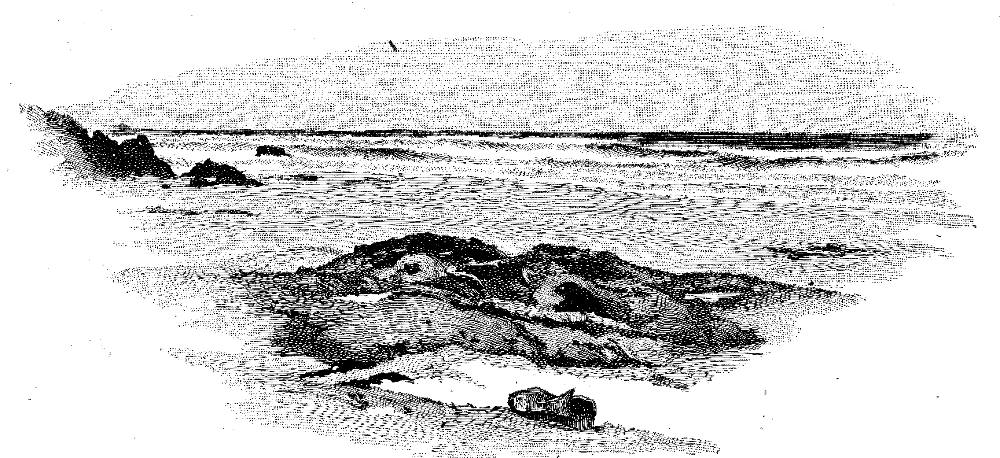

Shoes that were not fellows enables the reader to assess Crusoe's situation at a glance: he alone among the entire crew has survived, and the shoes remain unclaimed on the beach. Foot of page 33, vignetted: approximately 4.8 cm high by 10.5 cm wide.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Anticipated: Crusoe the Sole Survivor

I was now landed and safe on shore, and began to look up and thank God that my life was saved, in a case wherein there was some minutes before scarce any room to hope. I believe it is impossible to express, to the life, what the ecstasies and transports of the soul are, when it is so saved, as I may say, out of the very grave: and I do not wonder now at the custom, when a malefactor, who has the halter about his neck, is tied up, and just going to be turned off, and has a reprieve brought to him — I say, I do not wonder that they bring a surgeon with it, to let him blood that very moment they tell him of it, that the surprise may not drive the animal spirits from the heart and overwhelm him.

“For sudden joys, like griefs, confound at first.”

I walked about on the shore lifting up my hands, and my whole being, as I may say, wrapped up in a contemplation of my deliverance; making a thousand gestures and motions, which I cannot describe; reflecting upon all my comrades that were drowned, and that there should not be one soul saved but myself; for, as for them, I never saw them afterwards, or any sign of them, except three of their hats, one cap, and two shoes that were not fellows. [Chapter III, "Wrecked on a Desert Island," pp. 33-34]

Commentary

Paget complements I was now landed on the facing page by depicting the lifeless scene that Crusoe himself surveys from the shore. Paget seems to pride himself on using subtle visual effects to reveal the individual's psychology, rather than attempting the melodramatic staginess of previous illustrators in examining this situation.

Related Material

- The Reality of Shipwreck

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Related Scenes from Stothart (1790), the 1818 Children's Book, Cruikshank (1831), Wehnert (1862), and Cassell's (1863-64)

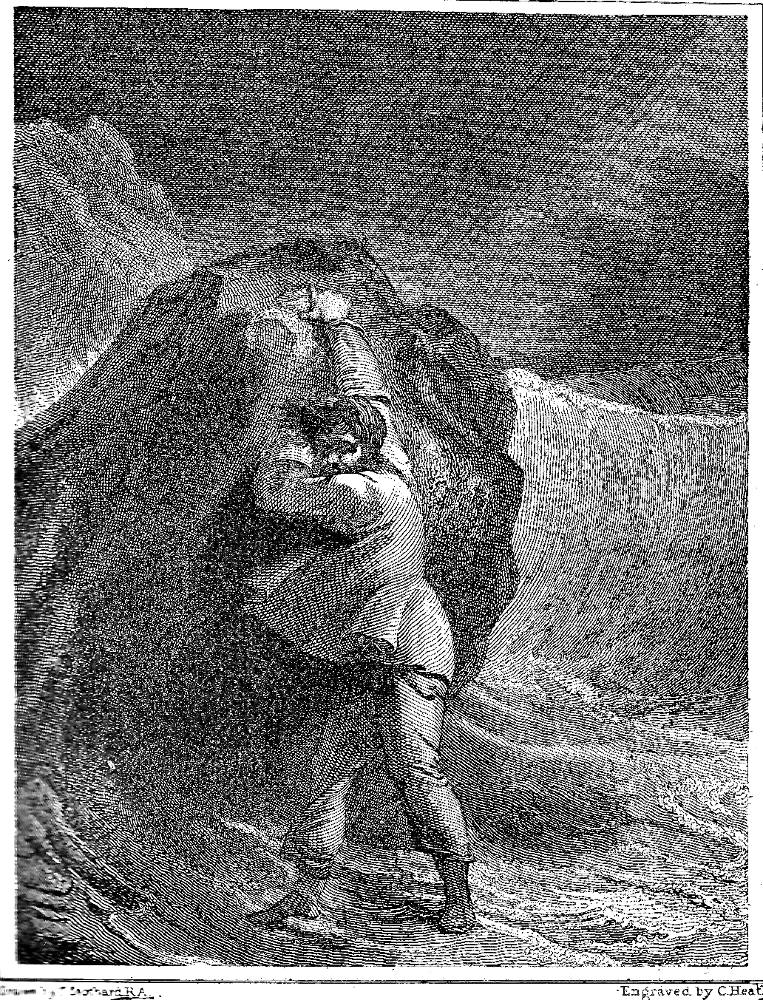

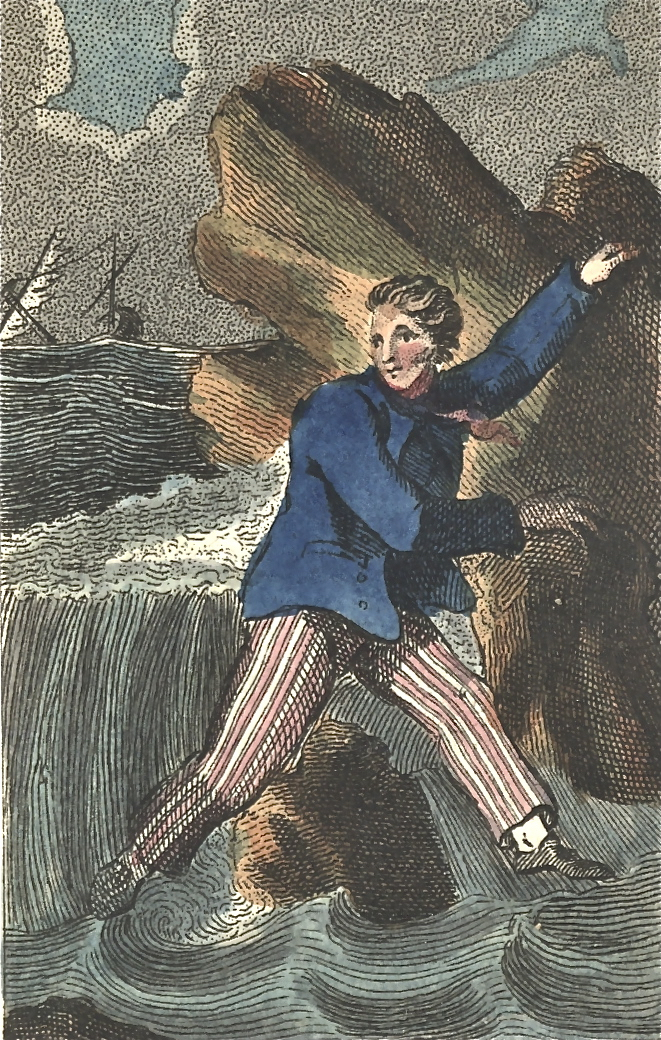

Right: Stothard's elegant realisation of Crusoe clinging to the rock, Centre: Wehnert's more dynamic realisation of the same episode, Crusoe saved on the island (1862: wood-engraving, Chapter III, "Wrecked on a Desert Island"). Right: Colourful children's book realisation of the same scene, but utterly lacking in realistic perspective: Robinson Crusoe cast away on the rock (1818). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Above: George Cruikshank's vignette of the castaway nearly overwhelmed by the breakers, Crusoe clinging to a rock on the beach. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Reference

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Of York, Mariner. As Related by Himself. With upwards of One Hundred Illustrations. London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1863-64.

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Of York, Mariner. As Related by Himself. With upwards of One Hundred and Twenty Original Illustrations by Walter Paget. London, Paris, and Melbourne: Cassell, 1891.

Last modified 25 April 2018