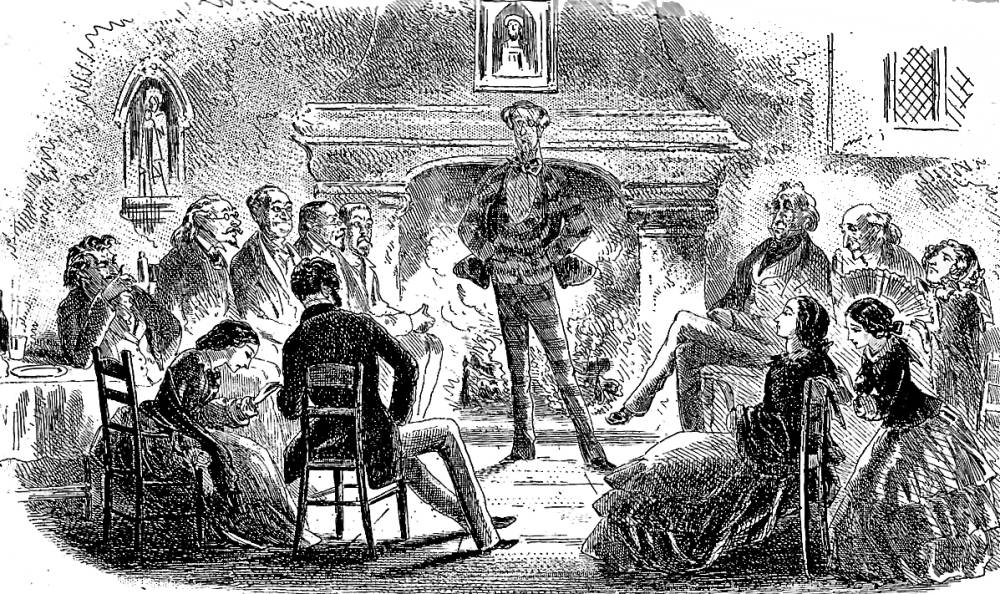

The Travellers by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne) from Dickens's Little Dorrit, Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 1, "Fellow-Travellers," facing p. 372 10.4 cm high by 17.8 cm wide, vignetted. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Image scan and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Realised

"You, madam," said the insinuating traveller, "have visited this spot before?"

"Yes," returned Mrs. General. "I have been here before. Let me commend you, my dear," to the former young lady, "to shade your face from the hot wood, after exposure to the mountain air and snow. You, too, my dear," to the other and younger lady, who immediately did so; while the former merely said, "Thank you, Mrs. General, I am perfectly comfortable, and prefer remaining as I am."

The brother, who had left his chair to open a piano that stood in the room, and who had whistled into it and shut it up again, now came strolling back to the fire with his glass in his eye. He was dressed in the very fullest and completest travelling trim. The world seemed hardly large enough to yield him an amount of travel proportionate to his equipment.

"These fellows are an immense time with supper," he drawled. "I wonder what they'll give us! Has anybody any idea?" — Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 1, "Fellow-Travellers," p. 374.

Commentary

The drawing technique is characteristic of Browne's style in the late 1850s and early 1860s at its best, with a concern for composition, a pleasant handling of faces, and something of a sparseness of background details. In some of these plates, however, there is a tendency toward excessively rigid symmetry, as in the very next one in this novel, "The Travellers" (Bk. 2, ch. 1). [Steig, 166-167]

The symmetry which Steig contends imposes a rigid organisation upon the composition is consistent with Dickens's description of the three "parties" waiting for their dinner in the parlour of the Alpine convent. The "insinuating traveller" is almost certainly Monsieur Blandois (extreme left, smoking) in the first chapter of the October 1856 (eleventh) instalment that marks the mid-point of the serial run. "The Chief" (William Dorrit) and his suite — his brother Frederick, his daughters Amy and Fanny, and their governess, Mrs. General, occupy the right-hand side, with Tip Dorrit in the rather loud suit and sporting a monocle, immediately before the fire, "roasting" himself. Aside from Blandois, already noted, the left-hand register includes Minnie and Henry Gowan ("the artist traveller," nearest the viewer, to whom Blandois has already attached himself), and the overtaking party whom Dickens explicitly describes: "The third party, which had ascended from the valley on the Italian side of the Pass, and had arrived first, were four in number: a plethoric, hungry, and silent German tutor in spectacles, on a tour with three young men, his pupils, all plethoric, hungry, and silent, and all in spectacles" (373). A "value-added" feature in the drawing of the international travellers is that Mrs. General's fan, not mentioned in the letterpress, forms a kind of halo around Amy Dorrit's head, right. To suggest that the setting is the refectory of a convent, Phiz has added a statue of the Virgin and the Child (left) and a portrait of Christ above the mantel of the fireplace. Unless one regards Tip's monocle as having symbolic value, the picture is without the kinds of embedded emblems that characterize his earlier work. While Phiz has sufficiently distinguished each of the nine male travellers, the three young women might all be sisters, as the illustrator's eye for feminine beauty tended to run towards this particular type of thin brunette. Nevertheless, through giving her a tentative, timid quality Phiz leaves us in doubt as to which young woman is Little Dorrit, and which the proud, self-centred Fanny. A typical Browne elaboration of upon the text is Minnie Gowan's fruitlessly attempting to engage her husband in conversation, implying that, although not long married, the couple are already growing apart.

Browne's greatest problem was that by now Dickens usurped his very function. The author had always written unusually pictorial prose. In Little Dorrit his writing became so graphically suggestive yet selective that it needed little visual help. [Cohen 114]

Although, as Valerie Browne Lester points out, the Phiz illustrations in Little Dorrit are often superfluous because of the descriptive power of the prose, Phiz's realisation of William Dorrit's continuing arrogance and self-importance marks a significant moment in the novel as this is the first illustration in the second book, "Riches." Wealth, as Phiz points out, has done nothing to improve either William or his daughter Fanny; their sudden wealth has merely served to magnify their petulance. Only Amy remains untouched by the unexpected windfall that has enabled the Dorrits to undertake the Grand Tour, complete with couriers and trains of pack-mules. On the other hand, Mahoney's illustration (below) underscores Blandois' conception of himself as a cunning wolf stalking the English "sheep" he intends to fleece, reintroducing the criminal mastermind in the narrative pictorial sequence. The illustration is situated after the initial description of the alpine situation, just as the travellers are about to arrive at the convent for dinner.

Scenes for the first chapter of Book the Second, "Riches," in the Diamond, Household, and Charles Dickens Library Editions, 1867-1910

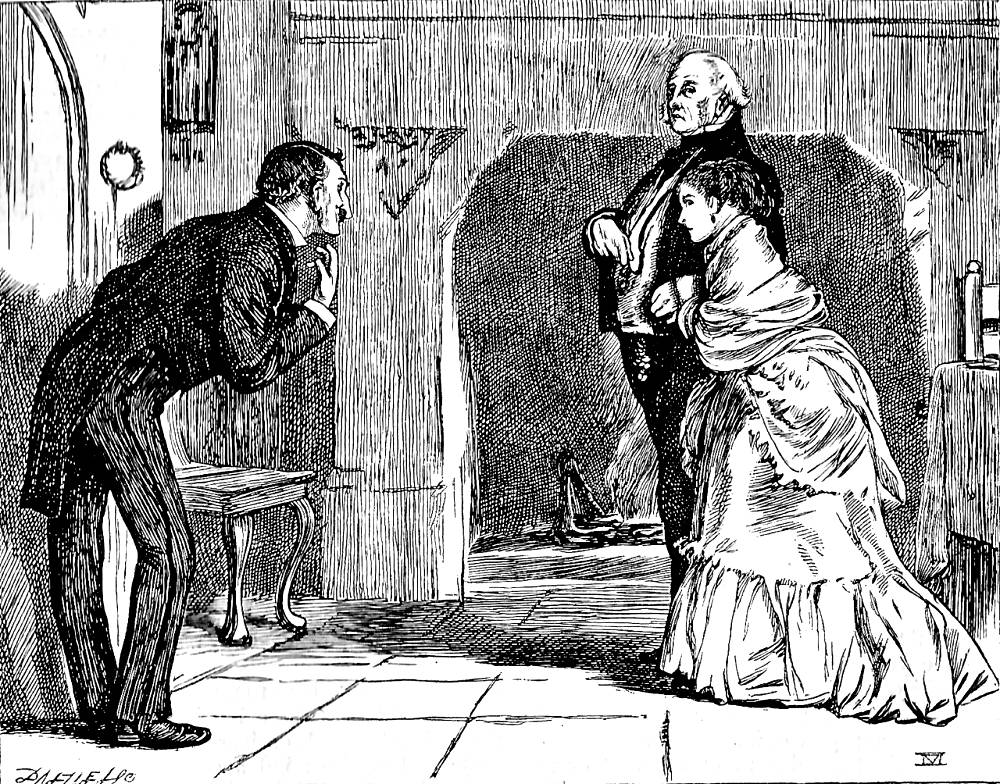

Left: Harry Furniss's version of William Dorrit as an egotistical English tourist on the Continent, Mr. Dorrit and the Swiss Innkeeper. Right: Sol Eytinge, Junior's study of the haughty English governess, the genteel widow whom William Dorrit has hired to "finish" his daughters, Mrs. General (1867). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

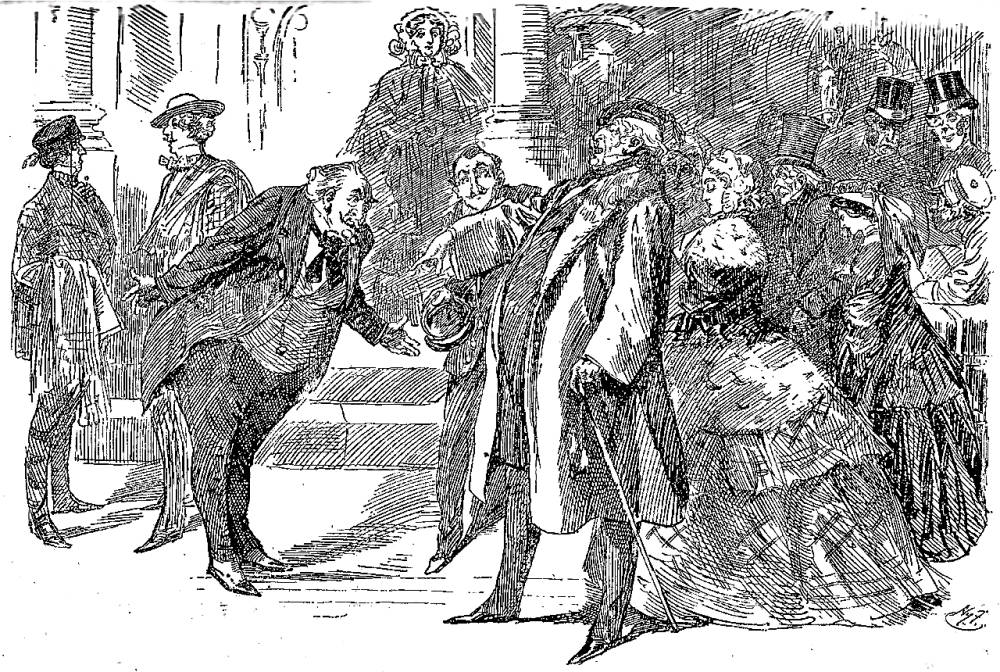

Above: James Mahoney's introduction of Rigaud (now, "Blandois") among the English travellers at the Swiss inn, As he kissed her hand, with his best manner and his daintiest smile, the young lady drew a little nearer to her father (Book 2, Ch. 1, in the 1873 Household Edition).[Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ["Phiz"]. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Authentic Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1901 [rpt. of the 1867 edition]. Vol. 12.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863. 4 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney [58 composite wood-block engravings]. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss [29 composite lithographs]. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

"Little Dorrit — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Muir, Percy. Victorian Illustrated Books. London: B. T. Batsford, 1971.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. The Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 8 May 2016