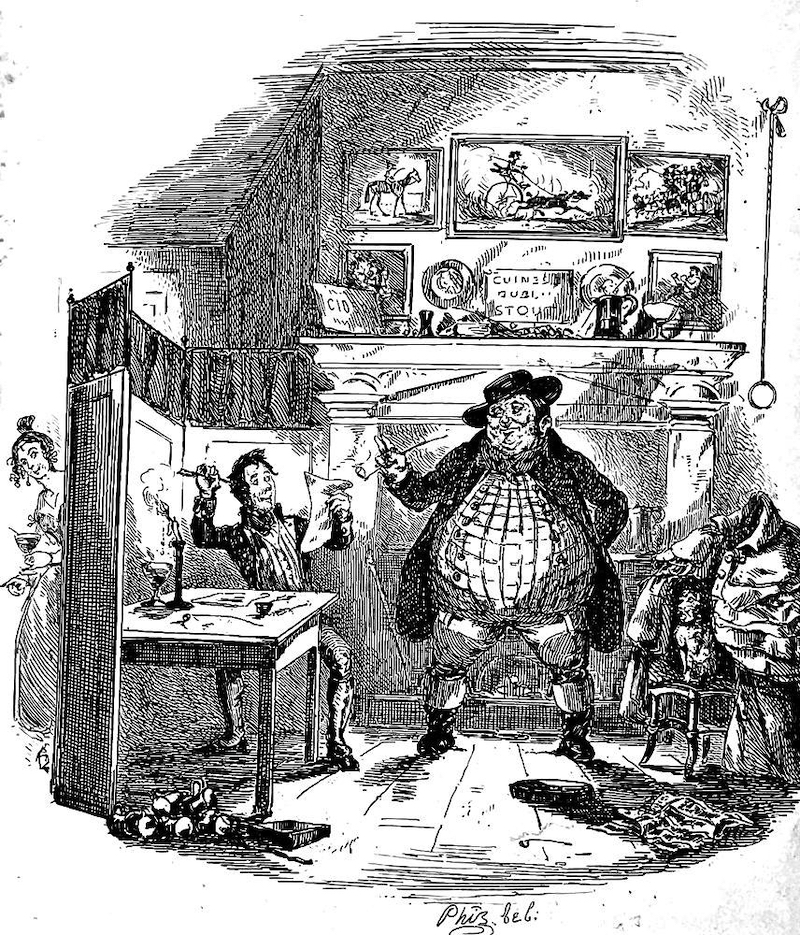

With a countenance greatly mollified by the softening influence of tobacco, requested him to "fire away." by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne). British Household Edition (1874) of Dickens's Pickwick Papers. 11.2 cm high by 14.3 cm wide (4 ⅜ by 5 ½ inches), framed, half-page, p. 225; referencing text on page 226; descriptive headline: "Cupid at The Blue Boar" (p. 225). [Click on the illustration to enlarge it.]

Passage Realised in the Two Phiz Illustrations (1837 and 1874)

We cannot distinctly say whether it was the prospect of the pipe, or the consolatory reflection that a fatal disposition to get married ran in the family, and couldn't be helped, which calmed Mr. Weller's feelings, and caused his grief to subside. We should be rather disposed to say that the result was attained by combining the two sources of consolation, for he repeated the second in a low tone, very frequently; ringing the bell meanwhile, to order in the first. He then divested himself of his upper coat; and lighting the pipe and placing himself in front of the fire with his back towards it, so that he could feel its full heat, and recline against the mantel-piece at the same time, turned towards Sam, and, with a countenance greatly mollified by the softening influence of tobacco, requested him to "fire away." [Chapter XXXIII, "Mr. Weller the Elder delivers some Critical Sentiments respecting Literary Composition. . . ," 226]

Commentary

Of the original 1836-37 illustrations for monthly serialisation of The Pickwick Papers that Phiz elected to redraft for the Chapman and Hall 1874 re-publication of the novel in the new Household Edition, the most faithful to the original serial engraving is The Valentine (March 1837). As usual, with the Household Edition, Phiz has re-captioned it with a quotation to underscore the precise moment illustrated. However, the juxtaposition of the characters and the principal elements of the setting — the parlour of the Blue Boar in the vicinity of Mansion House (which Nast has worked into the background of his illustration for Chapter XXXIII) — are largely unchanged. However, Phiz, with his fondness for a pretty female face and form, has introduced the barmaid who delivers Tony Weller's usual beverage ("a double glass of the inwariable"), even through the quotation points to a moment after she has delivered his "inwariable" and left the room. Significantly, Tony Weller is less corpulent and less a caricature in the 1873 revision, the face and form of Sam Weller are more mature and less diminutive, and the clutter on the mantelpiece has been replaced by a tidy arrangement of public-house memorabilia. Thus, in 1873, Phiz transformed his earlier Regency cartoon for Valentine's Day (actually 13 February 1831, ironically the day immediately preceding the momentous breach-of-promise trial of Bardell vs. Pickwick.

The Valentine by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne). This appeared in the March 1837 installment of the serial.

In the original engraving, Phiz exaggerates Tony Weller's stomach (producing a pear-shaped figure that completely blocks the fireplace from the reader's view), rendered Sam (left) a mere homunculus, and had a cat and Tony Weller's coachman's greatcoat occupy the small chair (right), devoting much of his attention and the reader's to the objects on the mantel and the paintings above it: The signs "Guiness Dublin Stout" (centre) and "Cider" (left) complement the tankards, and the various horse-racing and coaching pictures suggest an atmosphere at once "of the turf" and masculine. But Michael Steig sees significance not so much in these background details as in parallels between this illustration and "The Trial" because he interprets the writer's and the illustrator's intention to counterpoint the implications of romance for Pickwick in the latter illustration and his servant in the former, for, as befits their differing ages and social classes, they celebrate Valentine's Day with a distinct difference:

With increasing frequency as the novel advances, Dickens deals with various parallels and antitheses: comic, moral, sentimental, social, and institutional. Thus, the semi-illiterate coachman Tony Weller can give the genteel Pickwick advice about widows based on his own folly and consequent experience. And in The Valentine (Ch. 33), and The Trial (Ch. 34) these implicit parallels can be actively "read." The central link between Chapters 33 and 34 is a love letter. As a tenant, Pickwick has written innocent notes to Mrs. Bardell which are interpreted through a barrister's (Mr. Buzfuz's) allegory of innuendo to read as though they were love letters. Sam here, as elsewhere in the novel, parodies his master, when, inspired by a comically allegorical valentine in a shop window, he writes a declaration of love to Mary the housemaid. To stress the parallel, Dickens has Sam sign his letter, "Your love-sick/Pickwick" (Ch. 32, p. 345), a comment upon the ridiculous position in which Pickwick has found himself with Mrs. Bardell. Once this parallel is recognized, the similar composition in the two etchings suddenly becomes visible.

Although the second etching has many characters, it is, as much as the first, based upon a simple spatial relationship between a central, standing, admonitory figure and, on the left, the object of his exhortations. Sam, writing his letter, receives advice from his father, who gestures with his right hand to support his arguments; in the other illustration, Serjeant Buzfuz holds the "love letter," but he too gestures — toward Pickwick — with his right hand, and though Pickwick's expression is totally different from Sam's, he holds his arms in a similar position. Taken together, these two plates stress the thematic counterpoint of Sam and Pickwick which occurs throughout the novel from the cockney's first appearance: Sam relates to his father with a balanced mixture of love, respect, and independence, and he is invulnerable to the depredations of law, society, or women; Pickwick, having no father, and not yet properly fatherly himself (as he will be once he has forgiven Jingle and intervened for Winkle with his father) is vulnerable to women and the law. [Dickens and Phiz, pp. 34-35]

Right: This particular picture on which Sam Weller's eyes were fixed by Thomas Nast for the American Household Edition (1873).

Phiz's redrafted version of the twenty-seventh illustration in the monthly serial complements rather than duplicates Nast's thirty-seventh 1873 American Household Edition illustration for this chapter, This particular picture on which Sam Weller's eyes were fixed (p. 193). The clutter above the mantelpiece is resolved into clear images, although in the 1874 woodcut the tops of the pictures are cut off and we see the door to the right that was not revealed in the March 1837 engraving. The cat remains on his chair, and evidently Tony's outer coat (no longer clearly recognisable as such) has been draped over it; more significantly, perhaps, the scene's principal source of light (the fire immediately behind Tony) is not blazing with such intensity as in the 1837 engraving, implying that Sam is in much better control of his emotions and his indicting of the romantic epistle than his hapless master. In the engraving, an adolescent Sam holds up his sheet, and scratches his ear, as if uncertain of the effect of what he has written; in contrast, in the woodcut, a mature Sam (with much the same haircut) seems much more confident about the quality of his epistle. The presence of the attractive "young lady who superintended the domestic arrangements of the Blue Boar" (224) counterpoints Sam's protestation that he has no intention to marry and the less romantic view of sexual relations encapsulated in Tony Weller's down-to-earth observations about his wife, and about the possibility of his son's marrying. Curiously, Phiz has chosen to retain the fireplace as a backdrop, even though the text specifies that "Sam Weller sat himself down in a box near the stove" (225).

Related Material

- The complete list of illustrations by Seymour and Phiz for the original edition

- An introduction to the Household Edition (1871-79)

- Harry Furniss's illustrations for the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

Other artists who illustrated this work, 1836-1910

- Robert Seymour (1836)

- Thomas Onwhyn (1837)

- Felix Octavius Carr Darley (1861)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr. (1867)

- Thomas Nast (1873)

- Harry Furniss (1910)

- Clayton J. Clarke's Extra Illustrations for Player's Cigarettes (1910)

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. Formatting by George P. Landow. [You may use the images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File and Checkmark Books, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Robert Seymour, Robert Buss, and Phiz. London: Chapman and Hall, November 1837. With 32 additional illustrations by Thomas Onwhyn (London: E. Grattan, April-November 1837).

_____. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863. 4 vols.

_____. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Thomas Nast. The Household Edition. 22 vols. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1873. Vol. 2.

_____. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874. Vol. 5.

_____. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 2.

_____. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. Vol. 1.

_______. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Thomas Nast. The Household Edition. 16 vols. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1873. Vol. 4.

_______. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874. Vol. 6.

_______. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 2.

Guiliano, Edward, and Philip Collins, eds. The Annotated Dickens.2 vols. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1986. Vol. I.

Steig, Michael. Chapter 2. "The Beginnings of 'Phiz': Pickwick, Nickleby, and the Emergence from Caricature." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. P., 1978. 24-50.

Created 11 April 2012

Last updated 22 April 2024