obert Seymour, whose suicide created the opening for Browne's talents, was thirty-eight at his death, with better than a decade of experience in etching, lithography, and drawing on wood, as a creator of individually sold satirical prints, periodical caricaturist, designer of humorous sporting plates, and book illustrator. Browne was, in other words, a nonentity replacing a widely known and popular artist, and he took at first the pseudonym "N.E.M.O." — "no one" — suggesting a self-effacing hack laboring away for others. (When Dickens sixteen years later gave such a nom de plume to a character who very much fits this description, he may have been having a little joke at Browne's expense.) N.E.M.O. became Phiz — a more appropriate companion for Boz, as well as a logical title for one who did "phizzes" — with the third plate he did for Pickwick. Browne's first six etchings for Pickwick are as overall designs perhaps already superior to Seymour's efforts, but as Harvey has pointed out, Browne has trouble with the poses of his figures (Harvey, pp. 106-109.), and equal trouble, I think, creating adequately distinct faces; in this respect the schoolmistress in the sixth plate of this series is as wanting as Sam Weller in the second.

obert Seymour, whose suicide created the opening for Browne's talents, was thirty-eight at his death, with better than a decade of experience in etching, lithography, and drawing on wood, as a creator of individually sold satirical prints, periodical caricaturist, designer of humorous sporting plates, and book illustrator. Browne was, in other words, a nonentity replacing a widely known and popular artist, and he took at first the pseudonym "N.E.M.O." — "no one" — suggesting a self-effacing hack laboring away for others. (When Dickens sixteen years later gave such a nom de plume to a character who very much fits this description, he may have been having a little joke at Browne's expense.) N.E.M.O. became Phiz — a more appropriate companion for Boz, as well as a logical title for one who did "phizzes" — with the third plate he did for Pickwick. Browne's first six etchings for Pickwick are as overall designs perhaps already superior to Seymour's efforts, but as Harvey has pointed out, Browne has trouble with the poses of his figures (Harvey, pp. 106-109.), and equal trouble, I think, creating adequately distinct faces; in this respect the schoolmistress in the sixth plate of this series is as wanting as Sam Weller in the second.

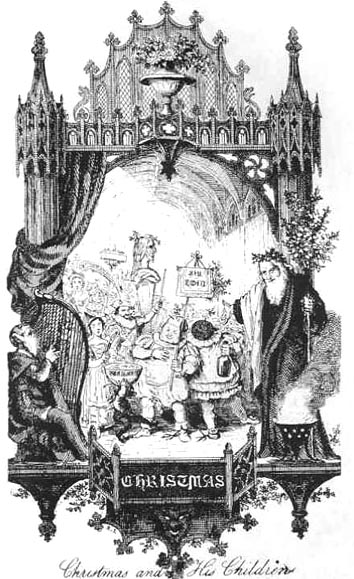

Frontispiece for Thomas K. Hervey's The Book of Christmas by Robert Seymour illustration 25].

The woodenness of the figures in these earliest plates is not much worse than Seymour's efforts, but with the seventh of his etchings, "Mr. Pickwick in the Pound," the young illustrator seems to have hit his stride. A comparison of [24/25] Seymour's Pickwick plates, together with those he did earlier in the year for Hervey's The Book of Christmas with Phiz's work for Pickwick reveals that the younger man, though by no means a slavish imitator, had carefully studied the elder's manner. Browne's work also generally reflects close affinities with older traditions of graphic satire. The figures in all of Browne's plates for Dickens' first novel are small, almost cramped, their bodies often contorted and their faces twisted into expressions which at times are insufficiently varied. Most noticeably, Phiz takes from Seymour the practice of modeling the faces by etching on them numerous curved lines that impart contorted grimaces to their expressions. Since Seymour, perhaps more directly and immediately than any other artist, provided Phiz with a mode in which to operate as Dickens' illustrator, the story of Phiz's development is the story of his movement away from that older style in a direction parallel to the development of Dickens' own art.

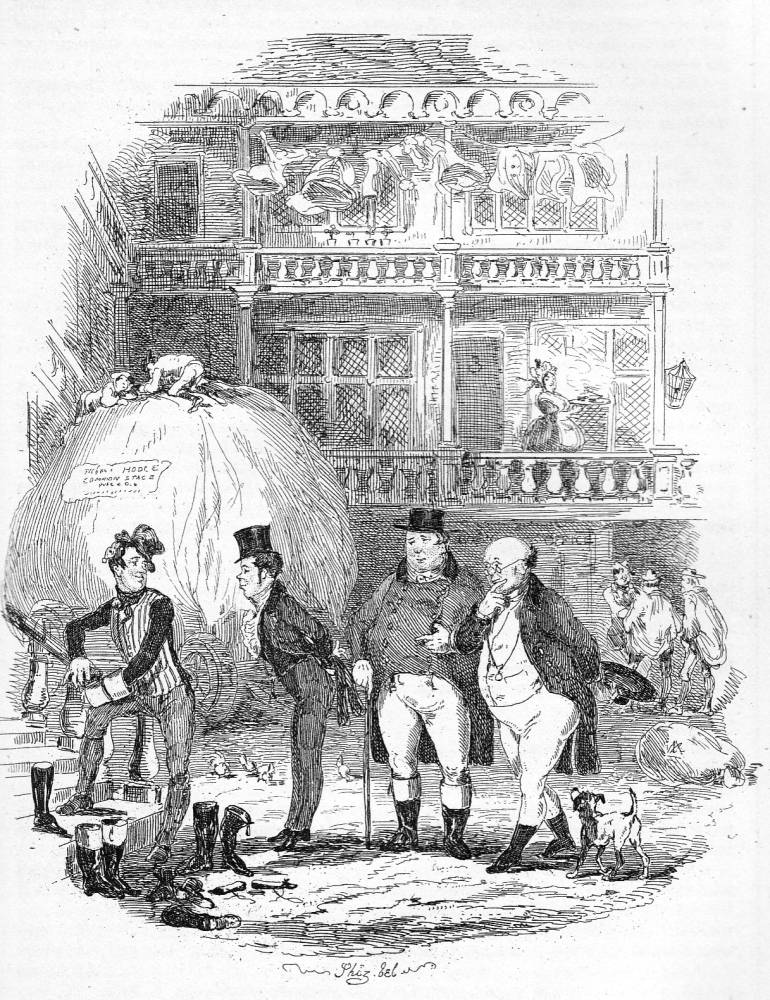

Left: First appearance of Mr. Samuel Weller illustration 13].

Almost from the very beginning, Phiz found himself called upon by the changes in the nature of Pickwick (including the character of Pickwick himself) to function as a different kind of illustrator. Except for the melodramatic tale of the melancholy clown, all the incidents Seymour had been required to depict were broadly comic. Pickwick was portrayed, both in text and etchings, as essentially a lovable fool, but Phiz's first commission was for two designs depicting events that for the first time involve Pickwick in incidents that require him to take morally responsible actions: Jingle's elopement with Rachael, in "The Breakdown" (ch. 9), and Jingle's encounter with the force of morality (as embodied in Mr. Wardle and Pickwick) and of the law (in Perker) in "First appearance of Mr. Samuel Weller" (ch. 10; captions given here for the Pickwick illustrations are those added in the 1838 edition, for which these two etchings plus ten others were etched anew with fundamental changes.). The first of this pair of etchings depicts the failure of passionate, resentful action, as it shows Pickwick temporarily fallen by the way (quite literally) and taunted by the triumphant rogue jingle, while the second depicts the impending victory of rational action, as the pursuers, now strengthened by the assistance of Perker the solicitor, are on the point of discovering the designs of their adversary.

Dickens, in the passages relevant to the first of these plates, as well as frequently elsewhere, makes great play with Pickwick's [25/26] tendency to burst into violent if ineffectual rages; in the second plate, reasonable action does temporarily triumph, but Dickens has not forgotten comedy and uses Sam's good-natured insolence as a means of deflating Pickwick's and especially Perker's self-importance. Phiz emphasizes this undercutting in a way which suggests an independent use of expressive iconography: he leads our eye from the jaunty cockney, Sam Weller, on the left, through the three gentlemen to the little dog on the right, who is contemplating Pickwick's calves with vicious intent.

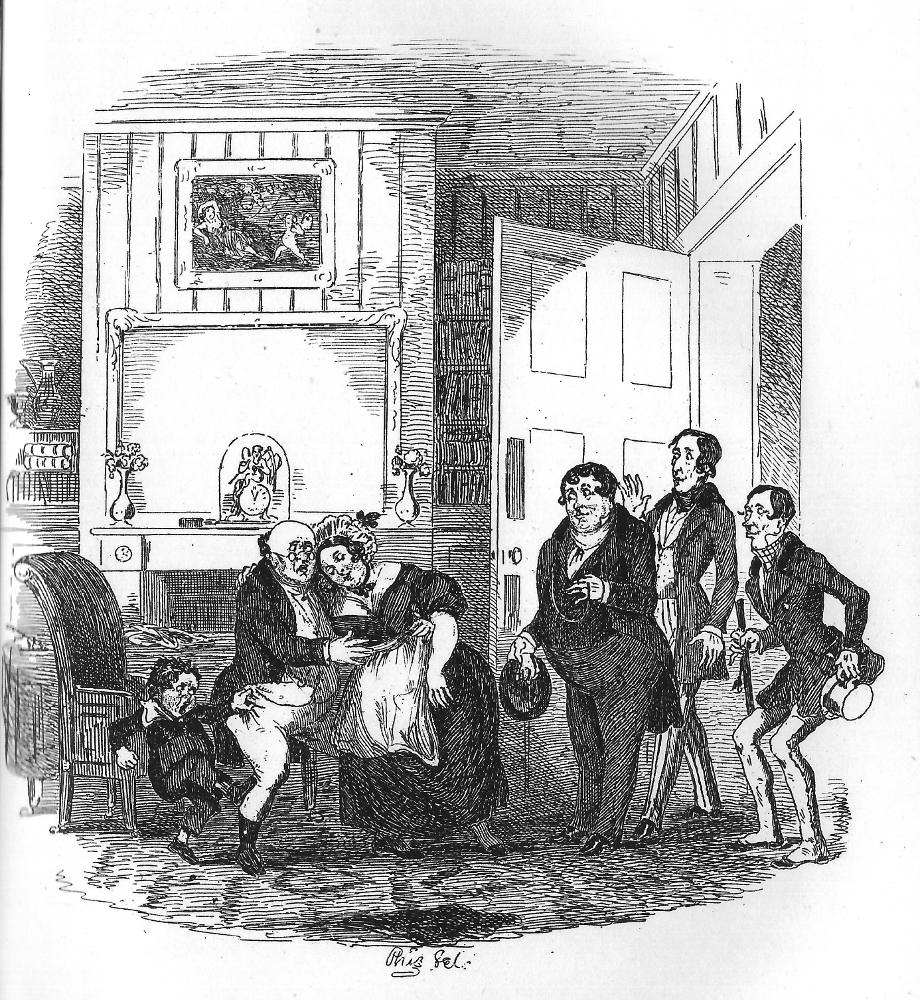

Mrs. Bardell faints in Mr. Pickwick's arms illustration 14].

The artist's execution is crude, perhaps (and much improved in the 1838 re-etching of this plate), but the dog's presence is important, for it is not mentioned in the text, and although Dickens could have suggested him to Browne it is just as likely that the artist included him as a natural compositional and thematic complement to the independent-minded Sam. Thus, Phiz demonstrates from the outset a capacity for composing illustrations which may be "read" like a Hogarth engraving, significant details and composition combining to elucidate Dickens' text. Browne's 1836 and 1838 versions of his third illustration, "Mrs. Bardell faints in Mr. Pickwick's arms" (ch. 12), provide an especially interesting example of this talent and its development. In the 1836 plate, with its harsh and scarcely relieved verticals, the rendering of both room and characters is rudimentary and stiff. Considered abstractly, the overall composition adequately conveys the point of the scene — Mr. Pickwick at the center holds Mrs. Bardell, harried by Master Bardell on one side while scrutinized by his friends on the other. Most interesting, however, are the rather tentatively etched details above the door: a stuffed owl and the sculptured head of what appears to be an elderly man. Presumably these constitute some kind of ironic reference to wisdom and sagacity, or perhaps the head simply suggests Pickwick's rather advanced age.

In the redesigned plate for the 1838 edition not only has Browne enormously improved the rendering of characters and scene so that the illustration comes alive in contrast to the stiff, formal feeling of the earlier one, but he eliminates the two vaguely emblematic details and introduces three new, much clearer ones: a framed picture above the mirror, showing Cupid aiming an arrow at a languid nude; on the chimneypiece, a pair of [26/27] vases with fresh flowers in them; and between these, an ornamental clock featuring Father Time with his scythe. The clock is immediately behind Pickwick's head, while the right-hand vase is behind Mrs. Bardell's, so that the clear implication is a lightly ironic commentary upon the conjunction of age and (relative) youth.

The Unwelcome Intruders illustration 15].

The picture of the God of Love aiming his arrow at a reclining woman is curiously similar to a detail in an earlier book illustration by George Cruikshank. While the detail's design could resemble the earlier etching by chance, the subject of the earlier plate makes this less likely. Entitled "The Unwelcome Intruders," it deals with an amorous adventure of the Duke of Cumberland and depicts three men entering a room and surprising the Duke in dishabille, while a lady runs off into another room (Moore, facing I, 121). The total composition is not similar to Browne's plate, but the connection of the situation with the Cupid detail suggests at the very least that Browne was influenced by his predecessor's etching, and perhaps that he was alluding to it — which would give extra comic point to the plight of Pickwick, who has no intention of becoming romantically involved with his landlady. One may also push further the interpretation of the other emblems, as the symbol of age on the mantel is flanked on both sides by a symbol of youth (the flowers), just as Pickwick is caught between the swooning landlady and her kicking child. In any case it is important to stress that Browne must have introduced all of these new emblems on his own intitiative, since Dickens would hardly have given fresh instructions for the re-etched plates in the 1838 bound volume. Given his great advances in drawing and etching during the course of Pickwick's publication in parts, Phiz was probably not satisfied to trace and re-etch his earlier designs, as he had to do with Seymour's (From Plate 22 on, Browne etched duplicate steels for the first edition; the earlier steels, not etched in duplicate, required re-etching because they were worn. (Two steels etched by Browne for Part III were to replace those done by Buss.)

In the combination of Father Time and Cupid, Browne uses emblematic details in a quite Hogarthian way; compare for example Hogarth's method of juxtaposing Cupid holding a scythe, representing the transitoriness of the flesh, with a detail of Orpheus and his music-tamed beasts, symbolizing the illusory nature of eternal concord on earth, in his family group, The Graham Children (Tate Gallery; Paulson, 1: 459). The details in the 1838 etching hint at a more serious and broader moral context for the [27/28] episode even as they comment upon its comic aspects. In discussing the plates to David Copperfield, we shall see how Phiz was to use yet another detail present in this Hogarth painting, along with another from the Mrs. Bardell plate.

Part VII of Pickwick Papers contains the first unequivocal example of a pair of Browne's illustrations designed to present both a visual and a thematic relationship. We must remember that originally the etchings were bound together separate from the text; thus, such parallelism should have been apparent to the first readers, although the lack of any contemporary testimony to this effect raises a special problem. For if there is little evidence (despite the undoubted importance of the illustrations in influencing the reception of the novels) that Browne's and Dickens' contemporaries saw the illustrations as comparable to Hogarthian "progresses," then modern scholars who argue for a serious iconography are in the strange position of claiming to have discovered both particular meanings and possibly a whole artistic mode of which the earliest readers and perhaps even the author, if not the illustrator, were unaware. But the apparent temerity of such claims may be mitigated by the reflection that Dickens, Browne and their contemporaries lacked not so much a perception of what they were doing as any formulated critical or aesthetic theory. The continuing lack of any such critical theory more than a hundred years after the fact can be explained on the grounds that Pickwick represented a new genre which lasted only two decades, to be replaced by a kind of illustrated novel which consciously rejected the Hogarthian tradition.

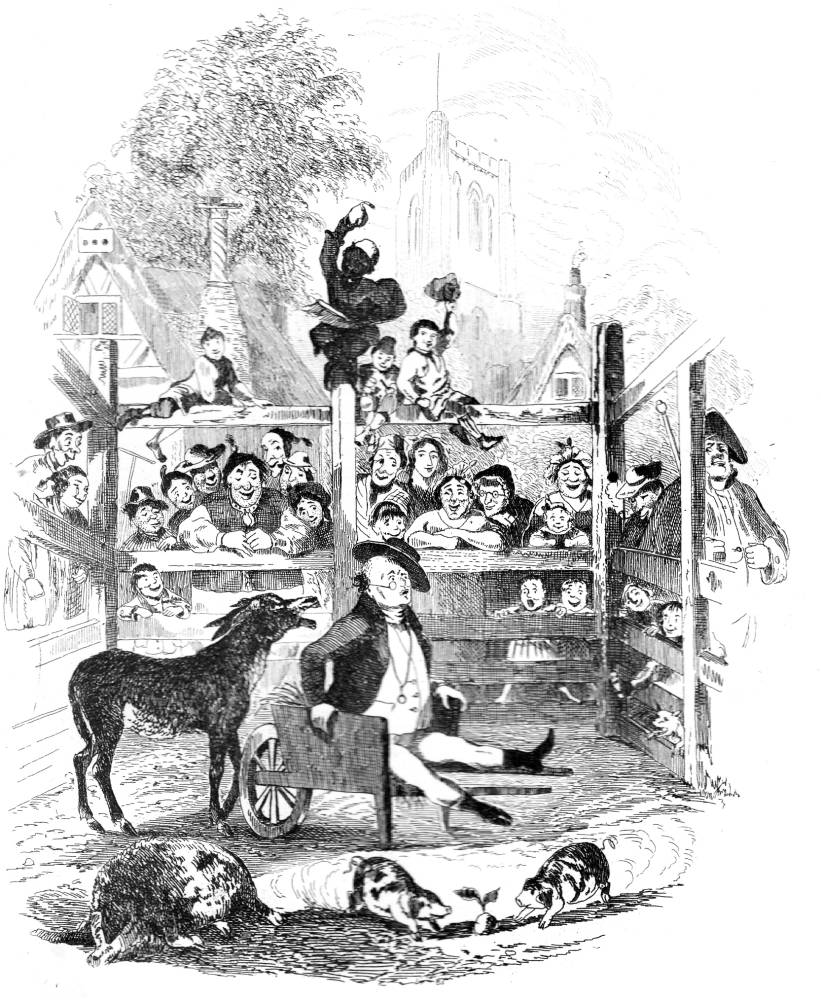

Plate and Study of Mr. Pickwick in the Pound illustrations 16-17].

Professor Robert L. Patten has analyzed the illustrations for Part VII at length, but it will be necessary here to discuss his arguments in some detail, as an example of both the advantages and dangers of trying to read a Dickens novel as a collaboration between author and illustrator. Patten performed the great service of pointing out what no one had ever noticed in print before, and what becomes perfectly obvious once one sees it: in "Mr. Pickwick in the Pound" (ch. 19) and "Mr. Pickwick & Sam in the attorneys' office" (ch. 20), Pickwick is in each case shown to be in the center of an enclosure, the object of mocking smiles or laughter from those on the other side of the [28/29] barriers. I am less satisfied with Patten's use of this important insight in interpreting the novel. According to Patten, in the first of the pair, Pickwick "for correction" of his folly in drinking too much "is put in a small informal prison, separating errant characters from the larger community"(p. 580). In contrast is the following plate, where "he is now isolated, not from the hearty villagers, but from Dodson and Fogg," (p. 582). thus reflecting Pickwick's moral superiority at this point. The novel's movement is from "communal harmony and benevolent good feeling to dissension and isolation,"(Ibid.) and then to spiritual enlightenment, for Pickwick's ability to join "the hilarious villagers" by laughing at himself" (p. 589) is related to the larger pattern of the novel, wherein Pickwick escapes "spiritual imprisonment" through forgiveness of Mrs. Bardell and Mr. Jingle (Ibid., p. 586.). Patten interprets the church building in the background of the pound plate as "iconographically" implying "Christian attitudes such as humility and forgiveness" (p. 585) while the donkeys and pigs function as emblems of Pickwick's folly and gluttony (p. 580).

Patten offers further valuable insights in comparing these two with "The Warden's Room" (ch. 41), and contrasting all three with the bonhomie of the Christmas etching. But one must return to the text to determine whether a given interpretation based on illustrations in fact accords with the novel. That Dickens intended a connection between the pound and attorneys' office plates is evident from the relevant chapters, in which such connections are more explicit textually than the.novelist tends to be in later years, when he lets the illustrations carry more of the burden of parallelism. First, Dickens underlines the parallels verbally by having Captain Boldwig, the ridiculously self-important landowner who puts the sleeping Pickwick in the pound, leave his victim with the words, "He shall not bully me — he shall not bully me" (ch. 19, p. 197). At the same time, the attorney, Fogg, is quoted by one of his clerks as having said to a legal victim, "Don't bully me, Sir" (ch. 20, p. 200), when it is really Fogg, like Boldwig, who is the bully. Second, when Pickwick awakes in the pound, the villagers' first response is to roar, "Here's a game" (ch. 19, p. 197), while the clerks say about their previous night's roistering, "That was a [29/30] game, wasn't it," and about Fogg's hoodwinking the poor Mr. Ramsey, "There was such a game with Fogg here" (ch. 20, p. 199).

Thus both the villagers and the clerks have a "game" at the expense of those victimized by the bullies who accuse the victims of their own crime. And Pickwick is of course a victim in both cases, as well. From this standpoint the two illustrations begin to look somewhat different from Professor Patten's description. If one takes the pound plate in isolation from Captain Boldwig, Dodson, and Fogg, then the emphasis upon folly and gluttony and the view of the mob (whom Dickens calls "many-headed") as a group of hearty villagers representing the community from which Pickwick is isolated seems at least plausible. But once the whole context is admitted this reading can no longer satisfy; folly and gluttony are there, and we can laugh at Pickwick's plight, but the mob is as much an object of Browne's satire as are the clerks, and behind the scenes Dodson and Fogg are more than agents of Pickwick's eventual "Christian" escape from "spiritual imprisonment" — though they may be that as well.

It is relevant at this point to recall Hogarth's brand of satire and how it differs from that of the graphic satirists who succeeded him in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Hogarth's "modern historical paintings" occasionally depict virtuous individuals, such as the girl Sarah Young in A Rake's Progress; but in general the satirist's shafts Strike everywhere, exempting no social class or political party. In the work of the later graphic satirists, however — including the very best — one is nearly always aware of extreme partisanship in Political, social, and moral matters. While not suggesting that Dickens' early works closely resemble Hogarth's sweeping satire, I believe one may say that Pickwick (like most of the other novels) is more in the spirit of Hogarth than of his successors. although some public or institutional figures like Boldwig, Dodson, and Fogg are conceived of as ridiculous and vicious beyond redemption, the novel is notably lacking in Prominent villains or heroes. One may draw extremely simple Christian lessons from Hogarth's prints, and similarly one may read the Pound plate of Pickwick as a simple moral tale in which the church is a Christian symbol. Equally, one could read this plate as an indictment of the church [30/31] and the law, with Pickwick as their victim and the crowd as the typically ignorant, conservative peasantry; in view of Browne's later use of churches this reading is at least as likely. In both this plate and its companion, a man who is essentially innocent becomes a victim of the power quest and sadism of others; and to suggest that Pickwick's "isolation" is primarily the result of his own spiritualshortcomings seems to me to oversysternatize, and thus oversimplify, both plates and text.

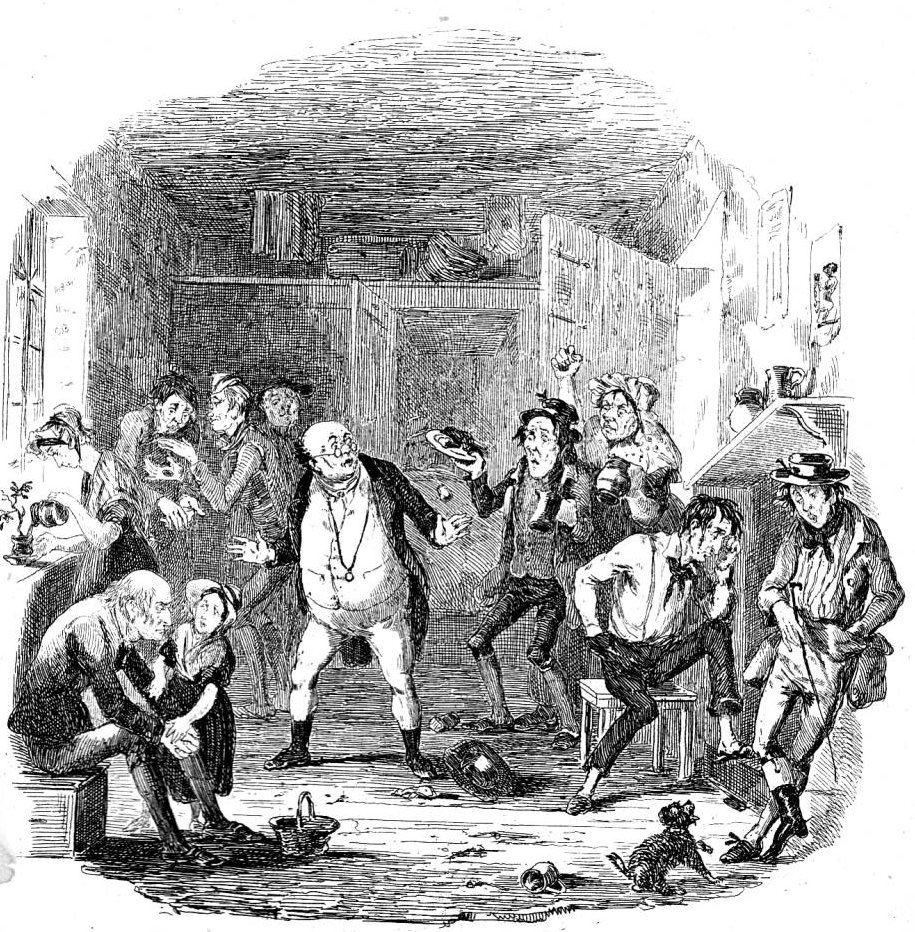

The plates for Part IX take further the problems of authority the mob, and the law, contrasted with the virtues of private domestic life. In the attorneys' office plate, Sam Weller was seen for the first time as consoler of Pickwick and as the mediator — through his healthy skepticism toward all constituted authority and all pretensions of social distinction — between the too vulnerable Pickwick and a world made up of ignorant and venal officials, men of petty and selfish passions, and designing women. In "Mr. Weller attacks the executive of Ipswich" (ch. 24) he becomes Pickwick's protector against authority as embodied in the mob. Sam's temporary victory in this plate is contrasted with his permanent one over Job Trotter in its companion, "Job Trotter encounters Sam in Mr. Muzzle's kitchen" (ch. 25). Sam and the pretty housemaid are noticed first, then the feasting cook, butler and the former pair are contrasted with job — his head preposterously big, like certain comic-grotesque figures in Gillray and George Cruikshank — who is isolated from the group by the vertical line formed by the door's edge; job is also farthest from the hearth. We find as well the third of several animal emblems in the book: a kitten attacks the remains of a meat pie, while its mother prepares to join in. This activity may be a reference to Jingle and Trotter and their attempt to carry off treasures from the Nupkins household, but while fragments of food have been left out for the cats, Job is excluded from the fellowship of the servants' kitchen.

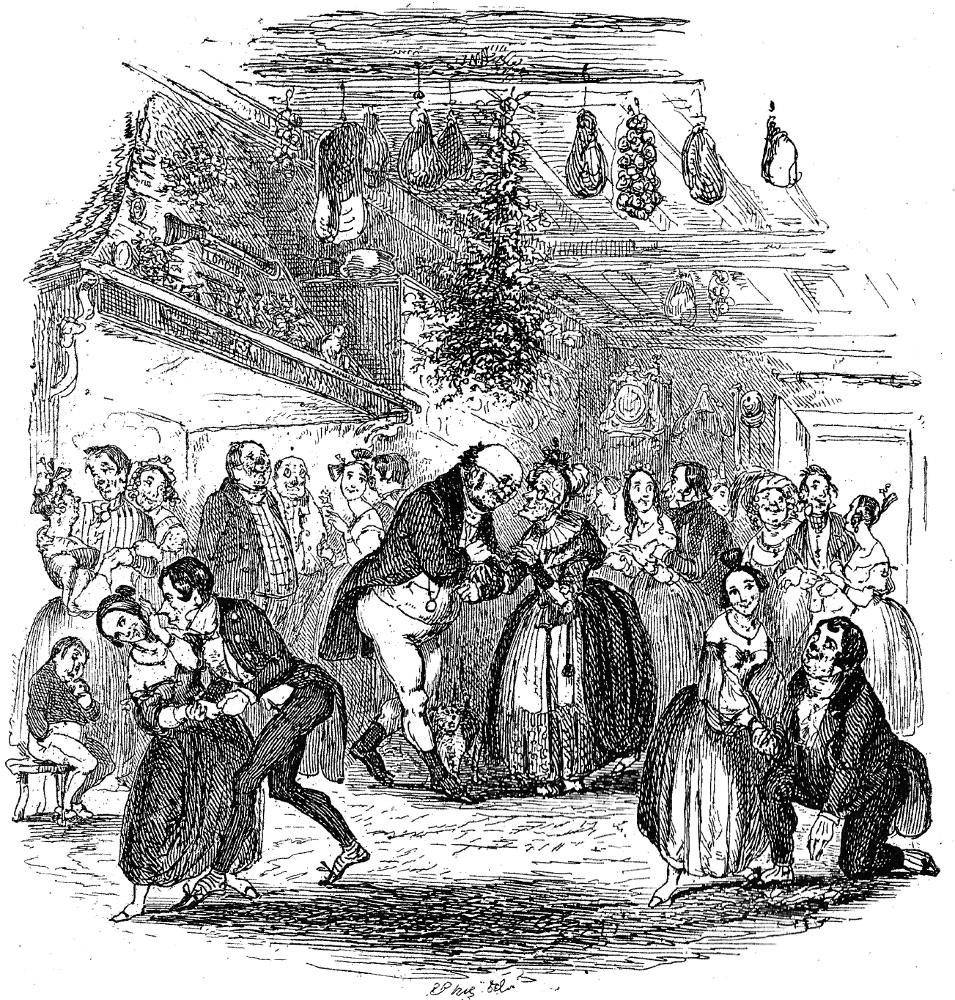

although food and eating occur frequently throughout Dickens novels, there is surely no other where they function so pervasively as symbols of community and love. In later novels though there are love feasts, these are often the special communion of two or three individuals in an alien environment (Tom [31/32] and Ruth Pinch's pudding, Pip and Joe's bread and butter); and feasting is as often the expression of selfishness — Squeers and his breakfasts at the Saracen's Head, Mrs. Camp and Betsy Prig, Major Bagstock. The genuine agape of Pickwick is expressed most directly in "Christmas Eve at Mr. Wardle's" (ch. 28). This is the first of Phiz's plates for Dickens to have had duplicate steels etched at the time of original publication in parts, rather than a new etching executed for the 1838 Pickwick (The variant steels are reproduced in J, pp. 40-42.); doubtless because the practice was a novelty for Browne, it is the only example among all the duplicated steels for which he made two different drawings and etched both, instead of tracing one drawing on the grounds of two or more steels. It is clear that Browne had trouble getting all the details from Dickens' text (including the earlier description of the Dingley Dell kitchen) into the drawing. The problem of including four couples in the crowded scene is solved by a triangular composition, with Pickwick and old Mrs. Wardle at the apex, and Winkle and Tupman with their partners at the comers, while Snodgrass and his partner are slightly back of Pickwick. But in what was probably the first steel (I base my assumption as to which is the first version on the fact of awkwardness corrected, and the subsequent addition of a caption only to the "second" in the 1838 edition. Cf. J, p. 40.), the fireplace is scarcely recognizable, Browne contorts Arabella's neck and head to an extreme degree, and gives the woman next to Wardle an imbecile expression and undue prominence.

Two versions of Christmas Eve at Mr Wardle's illustrations 18-20].

In his revised duplicate, Browne more or less solved these problems. He also substituted a cat rubbing against Pickwick's leg in place of the cat and dog in the center foreground of the original. The excised cat and dog are seen by Professor Patten as symbols of the special harmony of Christmastime at Dingley Dell ("Boz, Phiz, and Pickwick in the Pound," 581.), but I wonder. The dog sniffs at the cat, whose paw is raised in a cautionary way as though its claws are about to sink into the dog's nose; if this scene has any meaning, it would seem to parallel comically the behavior of Winkle and Arabella, who is coyly resisting his amorous advances. In Browne's illustrations, as in many of Hogarth's plates (see for example Plate V of A Rake's Progress) (This is the Rake's wedding, where the one-eyed bride is paralleled by a one-eyed dog; a similar detail is used by Browne in an illustration of "Fleet weddings," in Chronicles of Crime (1840).), domestic animals tend to imitate human beings, more often than not (as the dog in "First appearance of Mr. Samuel Weller") providing sardonic rather than cheerful commentary.

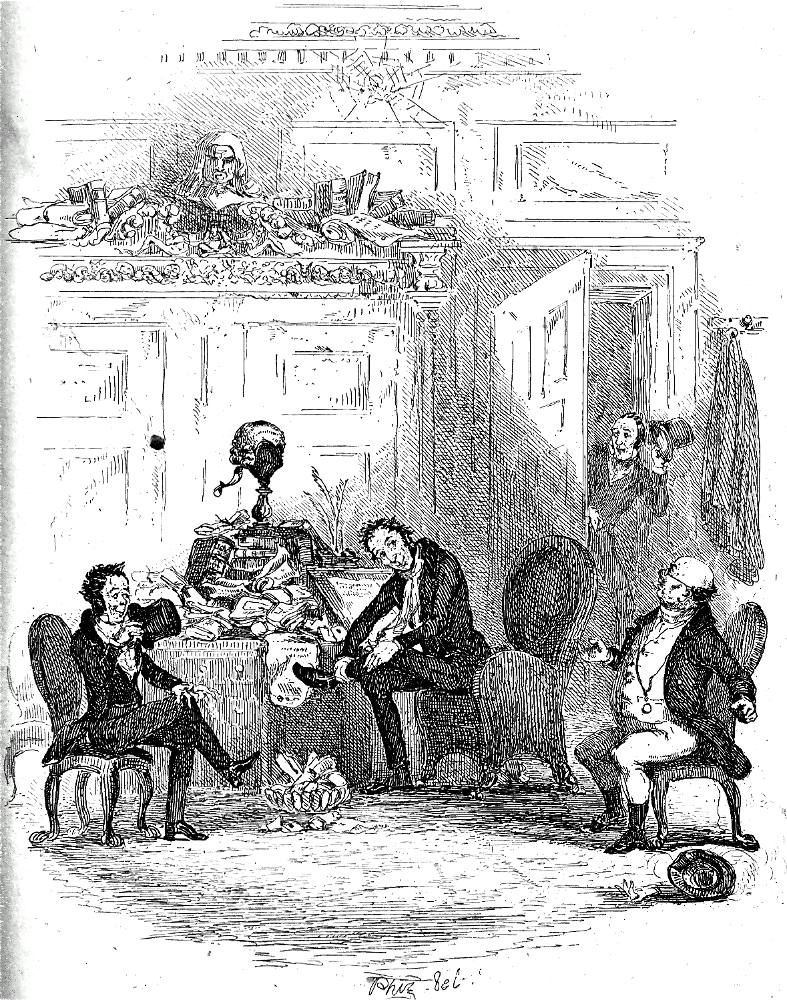

The first interview with Mr. Serjeant Snubbin illustration 21].

The contrasts of private good fellowship and the snares of the world of authority and law are suggested once again in "Mr. [32/33] Pickwick slides" (ch. 29), which has the hero surrounded by friends who will rescue and comfort him after his fall, and its companion plate, "erThe first interview with Mr. Serjeant Snubbin." In the latter, Pickwick is no long at the center of the composition, nor part of a friendly group. He is located on the extreme right edge, separated from both Snubbin and Perker by the door frame and the back of the barrister's chair, as though barrister and solicitor are in league against their client. Further, the half-open door links the unfledged assistant, Mr. Phunky, with the hapless Pickwick as a victim of the legal establishment.

The two steels for the Snubbin plate reveal some interesting differences that bear upon Phiz's conception of the illustration. In one steel (25B), the expression on Sniubbin's face is more in accord with Dickens' request that he should look "a great deal more sly, and knowing," and be "smiling compassionately at [Pickwick's] innocence." (P, 1: 222.) In both steels the design is composed with three overlapping triangles sharing the same base, and having as their apexes, respectively, the head of Serjeant Snubbin, his wig upon its block, and the grim bust of a judge which decorates the cabinet. Phiz has drawn Pickwick's face so that he appears to be looking at the wig rather than at the Serjeant, and the wig's centrality is consistent with the text: in employing Snubbin, Pickwick makes use of an impersonal force which has no more sympathy for him than does the wig, symbol of legal authority. Moreover, Snubbin's mild curiosity about this peculiar innocent seems to be mirrored by the expression of the amiable Mr. Perker — who is still a lawyer even if he is Pickwick's friend.

Directly above Snubbin's head is a spider web, into which flies are introduced in Steel B, indicating that it is not simply the law's mustiness which is represented. In addition, the cornice of the cabinet is ornamented in Steel B, and with the aid of a magnifying glass one can make out numerous bewigged and grinning heads with a horned one among them, suggesting that the legal forces arrayed against Pickwick are near relatives of the Father of Lies. If these subtleties of composition and detail are Browne's contribution, they surely grow out of the text and its implications: the wig is in Dickens' description of the room, yet its central position in the plate is the result of an interpretation of the relationship between law and humanity; the cobweb in the [33/34] first steel could simply reflect the general dirt and disorder mentioned in the text, but adding flies to it imparts a clearly emblematic meaning; and finally, decorating the cabinet in such a way that the artist alone is likely to be aware of the nature of the ornaments suggests a high degree of commitment on Browne's part to the craft he is pursuing — providing a running commentary, in visual language, upon the verbal text.

With increasing frequency as the novel advances, Dickens deals with various parallels and antitheses: comic, moral, sentimental, social, and institutional. Thus, the semi-illiterate coachman Tony Weller can give the genteel Pickwick advice about widows based on his own folly and consequent experience. And in "The Valentine" (ch. 32), and "The Trial" (ch. 33) these implicit parallels can be actively "read." The central link between chapters 32 and 33 is a love letter. As a tenant, Pickwick has written innocent notes to Mrs. Bardell which are interpreted through a barrister's (Mr. Buzfuz's) allegory of innuendo to read as though they were love letters. Sam here, as elsewhere in the novel, Parodies his master, when, inspired by a comically allegorical valentine in a shop window, he writes a declaration of love to Mary the housemaid. To stress the parallel, Dickens has Sam sign his letter, "Your love-sick/Pickwick" (ch. 32, p. 345), a comment upon the ridiculous position in which Pickwick has found himself with Mrs. Bardell. Once this parallel is recognized, the similar composition in the two etchings suddenly becomes visible.

although the second etching has many characters, it is, as much as the first, based upon a simple spatial relationship between a central, standing, admonitory figure and, on the left, the object of his exhortations. Sam, writing his letter, receives advice from his father, who gestures with his right hand to support his arguments; in the other illustration, Serjeant Buzfuz holds the "love letter," but he too gestures — toward Pickwick — with his right hand, and though Pickwick's expression is totally different from Sam's, he holds his arms in a similar position. Taken together, these two plates stress the thematic counterpoint of Sam and Pickwick which occurs throughout the novel from the cockney's first appearance: Sam relates to his father with a balanced [34/35] mixture of love, respect, and independence, and he is invulnerable to the depredations of law, society, or women; Pickwick, having no father, and not yet properly fatherly himself (as he will be once he has forgiven jingle and intervened for Winkle with his father) is vulnerable to women and the law.

The trial's result is depicted in the first of four prison plates, "Mr. Pickwick sits for his portrait" (ch. 39). As Patten points out, this plate recalls the two earlier illustrations in which Pickwick is confined within a small enclosure, the focus of a number of eyes; here, however, the observers are not laughing, but are memorizing Pickwick's features with a mind to confining him more securely. It is perhaps some indication of the prison episodes' importance for Dickens that for two of the prison etchings the novelist provide emblems in the text, as though especially concerned with thematic clarity. In the portrait plate, we have among the many bird-cages in Phiz's etchings, one whose significance is spelled out by the author: "'And a bird-cage,Sir,' said Sam. 'Veels vithin veels, a prison in a prison. Ain't it, Sir'" (ch. 39, p. 434). Sam also mentions the Dutch clock, implying that it too is a suitable background for a "portrait."

Discovery of Jingle in the Fleet illustration 22].

This plate resumes the thematic concerns of the illustration of Dodson and Fogg's office in portraying Sam Weller as Pickwick's adviser and protector, for in both Sam leans slightly over the sitting and dismayed Pickwick. By the next part, Pickwick has deprived himself of this moral support, determined to undergo alone the rigors of the Fleet. In both "The Warden's Room" (ch. 40) and "Discovery of Jingle in the Fleet," Pickwick expresses astonishment and perplexity. But in the former it is a reaction to the seeming anarchy of the situation and his own helplessness as a victim of his roommates' riotousness (An unused version, showing even more riotous behavior, is in the Pierpont Morgan Library, and reproduced in the Victoria Edition of Pickwick, 2 vols. (London: Chapman and Hall, 1887), 2: 201.); the "Rules of the Fleet" posted upon the wall (and nowhere mentioned in the text) seem an ironic comment upon the lack of order — and yet the actual rules of custom allow Pickwick to buy his way into a private room, for even here his money can prevent physical suffering.

The Rake's Progress, VII by William Hogarth. illustration 23].

In the third prison plate, Pickwick's amazement is at the presence of Jingle and the woebegone condition of this once jaunty rogue. Considering the text's requirements, this illustration demonstrates a real advance in Browne's ability to interpret his [35/36] author. The placement of Pickwick in the center, looking directly at jingle, impresses this encounter upon us as the primary one; our eye next takes in job Trotter, who is being followed by a woman demanding payment for food and drink (a detail not mentioned in the text, and recalling A Rake's Progress, VII. If this is indeed how we see the details, then Browne has reversed the time scheme, for Dickens first describes the secondary details, building up to the revelation of the rogues' presence. Assuming that we read the text first, the picture causes us to reconsider the same details in reverse order, taking us from the general to the specific, and then back to consider the general in relation to the particular. The result is perhaps what Hillis Miller has called "oscillation" between picture and text (p. 46). We first read about the ways in which the unnamed prisoners react to their circumstances, which prepares us to see Jingle and Trotter in a new light; then the revelation; then the illustration, moving us to reconsider the conditions of imprisonment, including the harrassment of prisoners for their debts incurred for mere subsistence. (There is also the famous antislavery poster, mentioned in Chapter 1.)

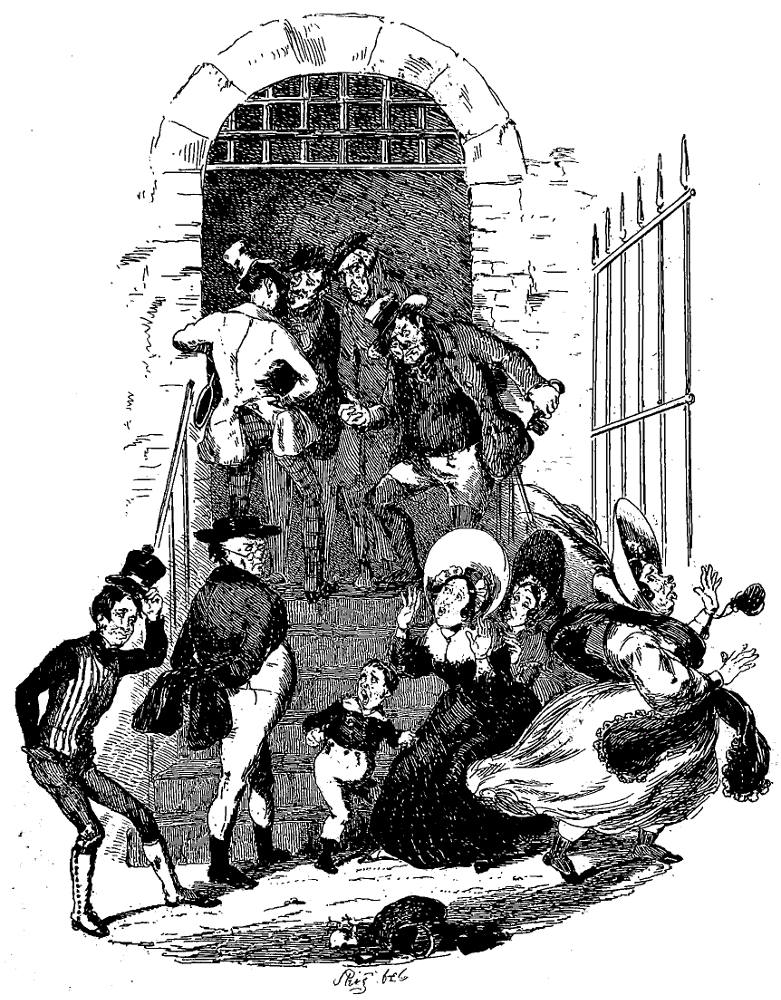

Mrs. Bardell encounters Mr. Pickwick in the prison illustration 24].

The last of the prison plates, "Mrs. Bardell encounters Mr. Pickwick in the prison" (ch. 44) adds nothing not specified in the text, but nonetheless it can be "read," and is a good example of Phiz's early mastery of the iconography of space and form. In this plate, the horizontal band formed by the main characters is juxtaposed both to the vertical of the gateway and to the dynamic thrust of the jailer, who appears to have just pushed the ladies and child down the steps. One reads from top to bottom left, and then to the right, just as one "sees" in the text the arrival at prison, the revelation to Mrs. Bardell that she is a prisoner, and then the encounter with Pickwick. The triangular arrangement, however, makes it possible to read the illustration in two directions, as though causally: from Mrs. Bardell up to the jailer and down to Pickwick, implying that her lawsuit has brought him to prison; or in reverse, beginning with Pickwick, implying that his stubborn adherence to principle has caused him unwittingly to make a victim out of his former landlady. Yet Pickwick and Mrs. Bardell also are part of the same compositional horizontal band, linked as victims of a vicious system.

A different kind of thematic emphasis occurs in "Mr. Bob Sawyer's mode of travelling" (ch. 49) where the seedy Sawyer [36/37] and his friend Ben Allen first come into contact with Pickwick. At this point the hero's transformation from bumbling fool into fountainhead of benevolence and wisdom is virtually complete, and yet suddenly we are given a violently comic episode in which Pickwick reverts to some of his early qualities, followed in the next plate by an even more broadly slapstick episode. If we accept the principle that the novel is moving toward the establishinent of a pastoral Pickwickian patriarchy for Winkle, Snodgrass, Sam, and their wives, the medical students introduced at this point represent the eruption of characteristics which the novel increasingly has either overcome or denied: self-interest, selfdramatization, lack of self-control, overindulgence in corporeal (if not carnal) pleasures, and even (in Ben and Bob's eagerness to "bleed" someone) indifference to others' physical sufferings. Browne's illustration even more than Dickens' text vividly expresses the subversiveness of these figures.

There are no details in the plate which are not in the text, but the "Irish family," whose "congratulations" are of a "rather boisterous description," is interpreted as a group of tinkers — two parents, seven children, and a dog — the father, the eldest boy, and one of the girls all saluting in direct imitation of Bob's gestures with bottle and sandwich. Pickwick's indignation is, in the text, to be converted with the help of a bottle of punch into a passive participation in the merriment; but in the etching he is caught at the moment when he is at the height of bourgeois respectability, in contrast to Bob, Sam Weller, and the Irish family. Phiz has thus apparently taken a generalized reference in the text and made it into the novel's only concrete reference to the lowest classes, implying that they are both a potential threat and a source of vitality beyond the range of Pickwick's compyehension. It is as though a bit of Oliver Twist, which Dickens was writing at this time, has through the agency of the two medical students invaded the generally more secure world of Pickwick. The accompanying plate, "The Rival Editors" (ch. 50), finds both Pickwick and Sam on the side of order, interfering in the absurd conflict between the editors and ignoring the medical students who circle them, brandishing their scalpels. This is the last broadly comic episode in the novel, and can be seen as a resolution, a laying to rest of the early Pickwick, as he and Sam have the [37/38] advantage over the ridiculous comic characters, and only the medical students suggest any continuation of Misrule (a term I have taken from traditional Christmas festivities, for reasons which will become apparent shortly).

As with all his subsequent novels published in separate monthly parts, Dickens had to write twice as much for the final portion of Pickwick, and Browne produced four illustrations instead of two. Following the procedures for all such novels save Nicholas Nickleby, two plates illustrate episodes in the final part, and the other two comprise frontispiece and title page, of which the first always, and the second sometimes, is of a recapitulatory or allegorical nature. The first two plates in Pickwick's final section are of minor importance (except perhaps in their emphasis upon eating and drinking), but the two final plates, because they become the first two in any bound edition, function both retrospectively and anticipatively. Phiz shows considerable inventiveness in carrying out what were likely Dickens' fairly general instructions. First of all, the two plates have certain broad connections: in the frontispiece, Sam and his master sit in a study, Sam showing Pickwick something in a book, while imps look in at them through a comically Gothic archway, gesticulating and laughing. In the title page vignette, Sam cheers his father, who is ducking Mr. Stiggins in a horse trough. This plate illustrates an actual episode from the novel, and is more naturalistically conceived than is the frontispiece, but both frontispiece and title page plates are linked visually by the archway through which Sam looks, for it is decorated with grotesque figures. Sam's gesture is further echoed by the figure on the inn's sign which menacingly waves a stick.

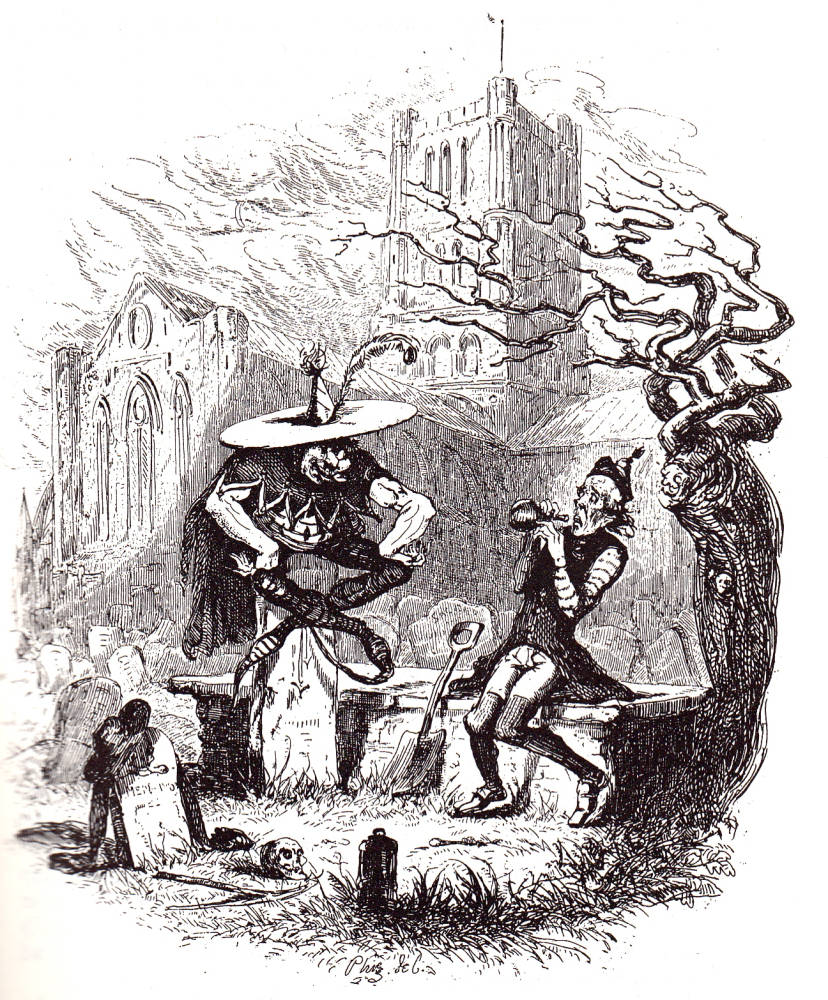

Three versions of The Goblin and the Sexton illustrations 10-12].

If we take the title page to represent the novel's violently active comic side, the frontispiece is, with qualifications, the reverse: a scene of contemplative repose, observed and ridiculed, however, by a group of comic subversives. The basic structure of the frontispiece is like a proscenium stage, below which an imp points sardonically at three of the main actors in the novel who are absent from the stage, Tupman, Winkle, and Snodgrass. Robert Patten has demonstrated that this frontispiece, through its visual references to books and tale-telling, its pantomime imps (one of whom is the goblin of an earlier plate, "The Goblin and [38/39] the Sexton" [ch. 28B](In the 1837 and 1838 editions, two chapters were numbered 28; 1 refer here to the second. I have followed throughout the chapter numbering of the first edition.), its globe, helmet, and shield, epitomizes the novel's use of the tale as a vehicle for conveying both experience and its evaluation (See Patten's "The Art of Pickwick's Interpolated Tales"). But in addition, the imps and goblins embody something of the tension in this novel between comedy as a moral vehicle and as a subversive force. Why, for example, is Gabriel Grub's goblin, whose function in the novel is to bring about the sexton's regeneration, here mocking Pickwick and Sam? And why is another such figure jeering at the Pickwickians?

The sources upon which Browne probably drew may throw some light on these questions. The stagelike frame has a long graphic tradition behind it, but Browne's most direct influence in its use seems to have been his predecessor, Robert Seymour. Though at first glance the frontispiece to Hervey's The Book of Christmas, "Christmas and His Children" (Illus. 25), does not obviously resemble Browne's design (Illus. 26), a moment's consideration reveals some parallels. In both, the central scene — intended to epitomize the book — is framed by a prosceniurn arch supported by Gothic columns. The stage is in each case revealed by a draped curtain, and both stages protrude into an apron. Below Seymour's stage is a satyr's head and below Browne's two, very similar to Seymour's. On either side in both pictures are stone brackets, occupied in Seymour's etching by a harper and Father Christmas and in Browne's by the imps and goblins. The goblin on the right points to the scene within, as does Father Christmas. There is also a possible link between this goblin and Seymour's Lord of Misrule (in both the frontispiece and a plate facing p. 213 of Hervey's book), and if this resemblance is more than accidental, the implication for Pickwick is that reason and reflection in Sam and Pickwick are mocked by mirth and unreason — which are themselves ritualistic and seasonal rather than uncontained or destructive. There are some further minor similarities between elements in the two books, but the basic parallels at the very least suggest the extent to which Phiz was working within current as well as eighteenth century graphic conventions.

If Browne was under the stylistic influence of Seymour in The Pickwick Papers, his use of iconographic methods for the purpose [39/40] of genuine interpretation and expression go beyond anything Seymour displayed as an illustrator. But Browne's illustrations for Nicholas Nickleby, which followed fairly closely in time, are a curious mixture. Much of the same kind of Seymourean awkwardness appears in some plates, while expressive iconography in the form of emblematic details or visual parallelism among plates is less prominent. Indeed, the general level of quality seern's lower, both in technique and invention. The difficulties with the Nickleby plates may stem in part from the same cause as Dickens' difficulties with the text, namely that the novelist is attempting something — which is new for him, a comic novel with a single adult protagonist, yet which contains both the picaresque and panoramic features of Pickwick and the more organized thematic qualities of Oliver Twist; the artist is thus perforce engaged on a new kind of venture, very different from either the earlier Pickwick or the contemporaneous Harry Lorrequer — a novel by Charles Lever both less serious and less unified than Pickwick.

Cover for Dickens's Nicholas Nickleby illustration 27].

The novel as a whole is, I believe, actually less a progress in the Hogarthian sense than is Pickwick, for Nicholas undergoes no real internal development, but simply faces a series of difficulties from which he is ultimately rescued by a pair of Pickwickian businessmen; and perhaps for this reason Browne has less to comment upon in his etchings than in the earlier novel, and much less than he will have in Martin Chuzzlewit. There are, however, at least the seeds of social commentary in the treatment of the moneylending villain, Ralph Nickleby, who is at the center of the most iconographically interesting challenge Browne was offered: the design for the serial version's front cover.

Of the seven such covers Browne designed for Dickens, two are wholly allegorical, containing no reference to the novel's characters or plot, while the other four combine allegory with material directly related to the text. Since the wrapper had to be ready by the time the first part was published, any details from the novel would have had to originate in either specific authorial instructions, a reading of some of the text of the first number, or both. The overall design for Nickleby is based on traditional motifs and is conceived in a general form that Browne was to use [40/41] several times. it is in the mode of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century engraved title pages which surround the words of the title with allegorical devices (Cf. the examples reproduced in Chew), a form carried into the nineteenth century by George Cruikshank among others, who adapted it for comic purposes in the frontispieces or titles to such works as Egan's Life in London (1821) and David Carey's Life in Paris (1822). The idea of dividing the design into images of good fortune on the left side and ill fortune on the right, with the figure of Fortuna, blindfolded, at the top center, may have been prompted by the novel's subtitle, "Containing a Faithful Account of the Fortunes, Misfortunes, Uprisings, Downfallings, and Complete Career of the Nickleby Family"; such left-right division is later used for the wrappers to Chuzzlewit, Dombey and Son, and David Copperfield.

Although the images across the top seem conventional, Phiz's comic imagination is evident in the two fat men on stilts and in the figures at the bottom of the design, and his emblematic imagination in the middle-aged man, a kerchief tied over his hat, who is seen making his way through a swamp, surrounded by mocking imps holding lanterns, with a church in the distance. These imps are will-o'-the-wisps or "Jack-o'-Lanterns" (an alternative term which George Cruikshank was to use for an etching in his Omnibus, 1842), which became a favorite emblem of Browne's, and his use of it in the frontispiece to Albert Smith's The Pottleton Legacy (1849) and the cover for Bleak House indicates that it had for him the specific meaning of the temptation of riches leading one astray into a swamp of materialism. It seems probable that the central figure is intended for Ralph Nickleby, and that Browne's conception was based on the eleventh paragraph of the novel:

On the death of his father, Ralph Nickleby, who had been some time before placed in a mercantile house in London, applied himself passionately to his old pursuit of money-getting, in which he speedily became so buried and absorbed, that he quite forgot his brother for many years; and if at times a recollection of his old playfellow broke upon him through the haze in which be lived — for gold conjures up a mist about a man more destructive of all his old senses and lulling to his feelings than the fumes of charcoal — it brought along with it a companion thought, that if [41/42] they were intimate he would want to borrow money of him: and Mr. Ralph Nickleby shrugged his shoulders, and said things were better as they were. (ch. 1, pp. 3-4)

In the design, the "mist" in which Ralph is enveloped thanks to his pursuit of gold is recalled by the darkness of the swamp, while the dulling of his senses may be represented by the scarf tied over his ears; his apparent ignoring of the church is a further extension of the idea of disregarding one's brother.

Certainly with Nicholas Nickleby Phiz worked harder than with any other assignment, for the plates were not merely etched in duplicate: according to Joharmsen's investigations (J., p. 77.), 14 were etched in quadruplicate, 18 in triplicate — a total of 117 steels. Such extra labor may in part account for the unevenness of the results. Whatever the case, the very first plate to Nicholas Nickleby, "Mr. Ralph Nickleby's first visit to his poor relations" (ch. 3), is a palpably theatrical scene which Browne had trouble handling. The characters are caught at a crucial moment, Ralph gruffly asserting his opinion of Nicholas' prospects, Nicholas making a gesture of protest, and Kate comforting their flustered and self-pitying mother. But except for Ralph, the figures have no life — Nicholas' face has little expression and his body is puppetlike, while the faces of his mother and sister are at best ambiguous. There is more to be said for the cramped, claustrophobic effect of the room, which reflects the family's barely shabby-genteel status and its dim future. Nicholas' figure.seems to be an attempt at the style of George Cruikshank which is lacking in that artist's symmetry and grace, while Kate's face here and elsewhere recalls the sentimental and idealized mode of the Keepsake or Friendship's Offering. although Phiz's virtuous women remain somewhat idealized throughout his career, they soon lose both the vapidity of expression and the raven tresses etched so that they look like hairpieces.

The peacock feathers displayed prominently over the mirror resemble those which appear so often in Phiz's work that it is tempting to dismiss them as mere space fillers. They may have been a common Victorian household ornament, but an artist with Phiz's evident knowledge of graphic traditions could hardly have been unaware of the symbolic meanings of such feathers. In [42/43] addition to pride, peacock feathers in a home are commonly associated with bad luck, perhaps because of the feathers' "spying eyes." (For a fuller discussion, see my 1973 article in ARIEL.) In the Nickleby plate they reflect the bad fortune that has hit the Nickleby family and foretell the worse fortune that is coming with Nicholas' employment by Squeers.

There is also an important technical aspect to this plate. At some point between the completion of Pickwick (October 1837) and the commencement of Nickleby (March 1838), Browne added to the crosshatch and other kinds of line and dot shading the use of a device known as the roulette, a small wheel at the end of a handle which, when rolled across the etching ground, produces a continuous series of dots, dashes, and the like, depending on the type of roulette. In the first plate of Nicholas Nickleby, its use can be seen in the carpet and on the lighter part of the ceiling; virtually every plate following has similar areas (The first use of the roulette by Browne that I have found is in Dickens' Sketches of Young Gentlemen, published in February 1838.). although it is primarily a time-saver and Browne often uses it mechanically, this technique introduces a new smoothness of tone into his shading and is often employed in careful combination with other, less mechanical techniques (See Harvey, pp. 183-85, for a discussion of Cruikshank's and Browne's use of the roulette.).

Despite the general weakness of the Nickleby plates, occasionally Browne shows evidence of having learned how to provide graphic continuity to sequences of plates stretched over more than a single part, in a novel whose action, however stilted, is less thoroughly episodic than Pickwick's. Thus, in Parts III and IV he must illustrate two related strands of the story, in a sequence which might be described as al-bl-b2-a2. The first and fourth, "The internal economy of Dotheboys Hall" (ch. 8) and "Nicholas astonishes Mr. Squeers and family" (ch. 13), feature the same characters in exactly the same setting; the two sandwiched between, "Kate Nickleby sitting to Miss La Creevy" (ch. 10), and "Newman Noggs leaves the ladies in the empty house" (ch. 11), both center on Kate's London adventures while Nicholas is in Yorkshire. In addition to the connections between the members of the pair in each part, there are also links between each two adjacent etchings in the series of four, and the first and fourth plates have causal links as well.

In each of the two middle plates, Kate is being shown kindness by an occentric but warmhearted person, but in the first Ralph Nickleby lurks in the wings while in the second the threat he represents is suggested in a secondary detail. As in the first his [43/44] secret watching of Kate is ironically mirrored by a cat watching for a mouse beneath the platform, so in the second there is an actual mouse, which in addition to indicating the shabbiness of the house may symbolize Kate's defenselessness against her uncle's plots. But Ralph's spying on Kate parallels in a general way the companion plate, in which Ralph's co-conspirator Squeers is leading Nicholas into the horrors of Dotheboys Hall. In contrast, the plates in Part TV are relatively hopeful, for in the first the two women have found a male ally in Newman Noggs, while in the second Nicholas has taken matters into his own hands.

The two Dotheboys Halls plates form a before-and-after se quence: in the first, Phiz challenges Cruikshank as an artist of the grotesquely pitiable, attempting something in the vein of "Oliver asks for more." It has been remarked that Dickens' text is superior to Phiz's etching, about which it seems difficult to say, as John Forster did about the text, that "Dotheboys was, like a piece by Hogarth, both ludicrous and terrible'" (Hunt, p. 134). Such a comparison seems too dismissive, but to contrast Browne with Cruikshank does reveal something about the former's virtues and limi tations. For Browne does not achieve, with his ragged, starving boys, anything like the preternatural effect of Cruikshank's workhouse lads who have been reduced to a subhuman level, with their stupefied expressions and sunken eyes, and even the bony structure of their faces and the shapes of their cropped heads. By contrast, Browne's are still recognizably boys, but boys with melodramatic faces either virtuous and horrified or wizened and grotesque.

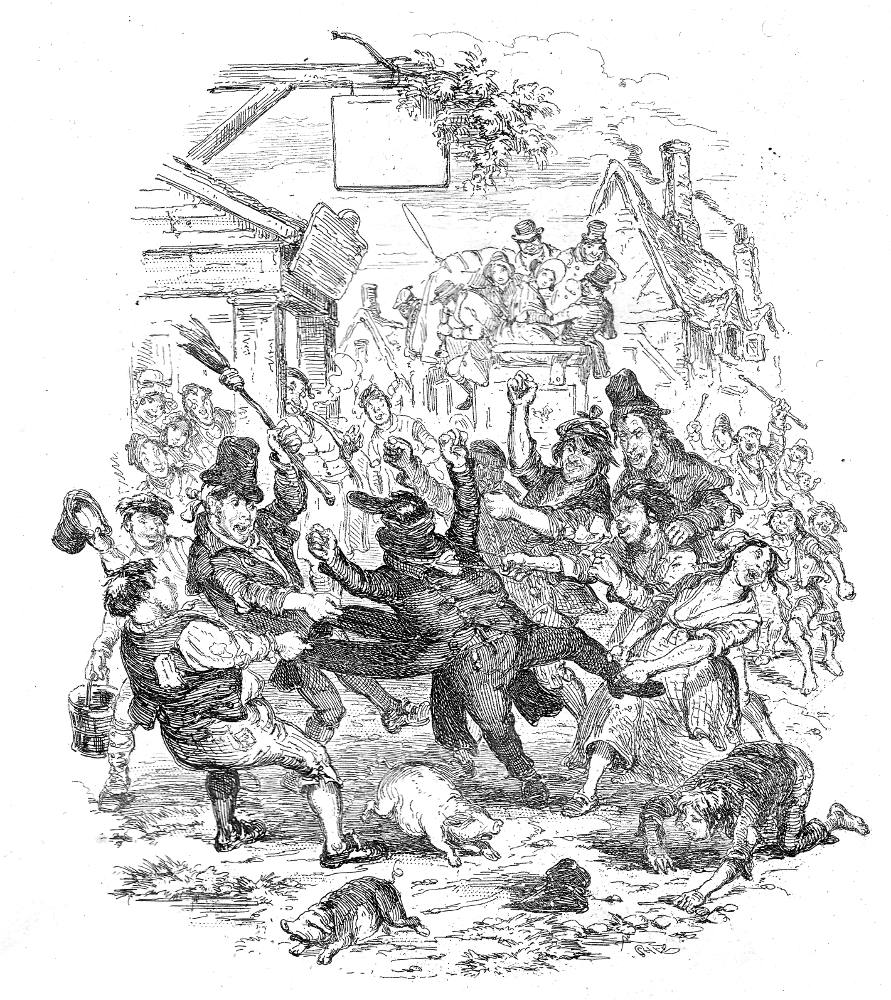

Mr. Crow well plucked illustration 30].

I think one grasps Browne's special talents only by considering this illustration along with its sequel. In the first, Nicholas is seen as simultaneously victim and oppressor: Squeers's stick is held with its point at his breast, so that the master-servant relationship is clear, yet at the same time Nicholas is, spatially, above the pupils, looking down upon them as if in his unwilling collaboration with Squeers he, too, is a "master." In the sequel we find Nicholas down in the boys' midst; he has become their ally against the Squeerses. The composition is of a kind favored by the early Phiz for scenes of violence, comic or real — a whirl of figures around one or two central ones; compare "Mr. Crow well plucked," in Lever's Charles O'Malley, 1840. [44/45] Nicholas' pose may be somewhat stagy, but nowhere near as much so as Dickens' verbal handling of Nicholas' denunciation of Squeers.

Another kind of continuity is established in Parts VII through X, where nearly all the plates deal in some way with acting, disguise, or pretense. As a group these plates emphasize the extent to which acting becomes a major metaphor in the novel. Unfortunately for the novel as a whole, the effect is to make those plates in which Nicholas appears seem largely melodramatic, since they seem to imply that there is little difference between the protagonist's life and acting. But such large considerations aside, most of the plates in question are extremely effective. For example, no one is more an actor than Mr. Mantalini in "The Professional Gentlemen at Madame Mantalini's" (ch. 21), except the same man in later plates, or the Kenwigs family. The portly Mr. Crummles and his boys look far more natural in "The Country Manager rehearses a Combat" (ch. 22), especially when we consider that they do not pretend to be what they are not. In this plate, Browne implies a complex relation of acting to reality by including both a portrait of the fat bost, who has some resemblance to Crummles, and a picture of Don Quixote and San Cho Panza. Thus, the illustration is a graphic version of a novel that deals with acting and pretense, and within that illustration there is yet another, based upon a book which is in turn a fiction about fiction, and the chivalric pretensions of Don Quixote. But the Quixote reference here applies also to Nicholas and Smike, who have set out in the world to seek their fortunes — a quest which turns out in a sense to be futile, since Nicholas ultimately must depend upon the benevolence of others.

We are actually on the stage in "The great bespeak for Miss Snevellici" (ch. 24), which presents the reality-fiction relationship in a different way. The illustration shows nothing of the actors and only a bit of the stage; because of the way they are framed by a scenic flat, footlights, the left side of the stage, and theorchestra, the members of the audience appear to be the ones Putting on the performance. Much in the style of a caricaturist of individual faces, Phiz has stressed the audience's oddities, their individual eccentricities and exaggerated behavior, which is as conventionalized in its way as actors' — the overeffusiveness of [45/46] the Borums, the stereotyped demeanor of the smitten young officer, the transfixion of the ginger-beer boy. All of this is in the text except for the basic graphic device, the exclusion of the actors and the theatrical framing of the audience.

The plates for Part IX further convey Dickens' and Phiz's vision of a confusion between appearance and reality. In "Affectionate behaviour of Messrs. Pyke & Pluck" (ch. 27), Sir Mulberry's two henchmen are performing for the benefit of Mrs. Nickleby, who in her stupidity — which is actually stereotyped behavior operating as a defense against realityof course does not know it is a performance. The falsity of Pyke and Pluck (who are after all only acting out their everyday roles) contrasts with the range of genuine emotion expressed by the costumed actors in the companion plate, "Nicholas hints at the probability of his leaving the company" (ch. 29). Mrs. Crummles' costume as a queen does not prevent her surprise and consternation from seeming genuine, nor do their disguises as savage and demon conceal the glee of the two actors at lower left at the prospective departure of their rival. As usual, Nicholas has the stagiest expression of all, and he is not even in stage dress.

The most interesting plates in the remainder of the novel include several which deal with the novel's villains, and one particularly successful comic illustration. Squeers, so roundly defeated by Nicholas back in the fourth number, has a temporary triumph in "A sudden recognition, unexpected on both sides" (ch. 38). One of Phiz's most complex creations for this novel, the illustration is suggestive as to the ways artist and author worked together. Its major details, including the manner in which Squeers has hooked Smike with his umbrella, the hod carriers, the schoolboy and apple woman, are all in Dickens' text, and were probably taken by Browne from a portion of the manuscript sent to him, if not from detailed instructions. The note by Dickens on the surviving drawing ("I don't think Smike is frightened enough or Squeers earnest enough — for my purpose") (P, 1:513. The drawing is in DH, and is reproduced in Kitton, fac. p. 64.) does not tell us very much, for we have no way of knowing how much Browne finally altered the faces, the drawing being much like the etching. But Browne seems to have added details not in the text: the fishing tackle shop with its realistic sign, alluding to Squeers's "hooking" of Smike; and the notice, "Seminary for [46/47] Young Ladies / French by a Native," an oblique comment upon the Yorkshire "seminary" to which Squeers wishes to return Smike.

The details in the right half of the bac ford to "call up one Browne's response to Squeers's telling Wack of the coaches" (p. 374), since a coach is shown waiting by the curb with a somnolent coachman on the box. But in the street itself Phiz shows an omnibus apparently racing another vehicle, whose horses are visible in full flight immediately behind. The omnibus driver is vigorously whipping his animals, while the omnibus cad standing at the rear sarcastically pretends to look at the pursuing vehicle through his purse as if it were a monocle; a face, frightened by the vehicle's speed, looks out of the rear of the omnibus. The whipping of the horses may be intended as a forecast of the gleeful "threshing" Smike will soon receive in a coach, and the anxiety of the passenger, the race of coaches, and above all the sneering look of the "cad," mirror the imminent abduction of Smike from his friends, who, however, will soon be on the trail of the Squeerses.

Three illustrations, in Parts VI, X, and XVI, feature the upper-class villain, Sir Mulberry Hawk, and his foolish young follower, Lord Frederick Verisopht. These names are less Dickensian than they are Hogarthian, reminding one of Tom Rakewell, Moll Hackabout, and Lord Squanderfield, and while all three plates make use of extreme caricatural technique rather than the subtler character drawing of Hogarth, the first two use art objects emblematically, while the second and third express meaning through their disposition of forms. Thus, in "Miss Nickleby introduced to her Uncle's friends" (ch. 19), the introduction of Innocence to Lust is paralleled by the juxtaposition on the mantelpiece of what looks like an extremely modest and shrinking figurine with a decorative clock clearly representing Vulcan (or perhaps Bacchus) in his violent and lustful ascendancy with two fair maidens at his feet. A painting above Lord Frederick's head might be an emblematic depiction of a storm engulfing a ship (or a church?), but Phiz was less careful with such details in these early years than he later became, and the painting varies so greatly among the three steels that it is impossible to be certain. [47/48]

The visual structure of "Nicholas attracted by the mention Of his Sister's name in the Coffee Room" (ch. 32) is such that the vicious noblemen seem to be triumphant, for they occupy the center and top of the design, while Nicholas is far below them. Dickens describes the room as having been decorated with the "choicest specimens of French paper, enriched with a gilded cornice of elegant design" (ch. 32, p. 310), but Browne's interpretation adds a new dimension not directly stated in the text. The wallpapers in the etching depict what look like Arabian Nights scenes, although no particular tales can be identified. The implication is that these members of the upper classes inhabit a world of voluptuousness and vicious make-believe, a world opposed and eventually defeated in the novel by the morally responsible middle classes. But there is a more specific comment in the right-hand detail, which shows one man reverently bowed down before an imperious standing figure; since they are before a castle, and their positions parallel those of Hawk and Nicholas, the lower orders' proper attitude towards the nobility (from the upper-class point of view) is suggested. Nicholas, of course, is about to rise up and challenge Sir Mulberry and to scar his face, so that the detail on the wall is clearly sardonic.

Hogarth's A Midnight Modern Conversation illustration 33].

The downfall of Hawk and his gull, Verisopht, is depicted in "The last brawl between Sir Mulbery and his pupil" (ch. 50). Its setting is described by Dickens in vivid but visually unspecific terms, in a passage which begins, "The excitement of play, hot rooms, and glaring lights, was not calculated to allay the fever of the time. In that giddy whirl of noise and confusion the men were delirious" (ch. 50, p. 500). The description reminds one of Plate VI, the gambling den, of A Rake's Progress, although such a sense of confusion is more evident in Hogarth's murky painting of the subject than in the precise lines of his engraving. But whether or not Dickens had Hogarth's gambling hell in mind, Phiz's overturned chairs and gamblers (not in Dickens' text) recall rather Hogarth's A Midnight Modern Conversation. although he does derive directly from the text, the man standing on the table, forming the apex of the pyramidal design, gives the whole scene something of the composition of the latter Hogarth engraving, whose apex is a similarly standing man, gesticulating with a glass.[48/49]

The fevered chaos of Dickens' description is reflected in the playing cards suspended in mid-air and the unstable position of the fallen man at lower right; the solid band of figures across the center of the design also suggests something of the feverish atmosphere. We remain, however, faced with a serious question as to how well the general mode in which Phiz works suits Dickens' more subjective and impressionistic passages. Without referring explicitly to this problem, one critic has gone so far as to argue that there is a disparity between the fantastic and dreamlike subject matter of such an artist as Cruikshank and the very precise, controlled nature of his etched line; I believe the problem to be more complicated than this critic seems to recognize, but something of his argument could certainly be applied to Phiz as illustrator of Dickens (Stoehr, p. 276). Without claiming that each and every illustration accords with the mode of the particular passage being illustrated, I think it is possible to show that (at least through Little Dorrit) Browne strove to conceive methods that would fit with his author's stylistic development. In "The last brawl between Sir Mulbery and his pupil" both the possible allusion to Hogarth and the way Browne chose to deal with the crowd especially in the dark tonality of the central band of figures indicate that his methods were far from static, even if they were at this stage dominated by a caricatural mode.

Browne's caricatural method of character portrayal is perhaps most happily employed in the illustration of what must be considered a minor incident in the story, though it is one of the most memorable, and foreshadows Dickens' almost surreal comic in ventiveness in later novels. The escaped madman in "The Gentleman next door declares his passion for Mrs. Nickleby" (ch. 41) is portrayed as a grotesque through the heavy use of etched lines on his face, and Mrs. Nickleby's simper is equally caricatural. Further, the shapes of the vegetables he has thrown over the wall are more evidently phallic than anything short of a much more explicit text could convey. But Browne employs other modes as well. Kate appears once again as a simpering maiden out of a Keepsake book, while the two birds at upper left, touching be in the sky, comment amusingly on Mrs. Nickleby's self-delusion about her suitor's love for her. Finally, the handling of foliage is an example of a new pictorial richness in Browne's technique. [49/50]

Browne is in general less successful with the sentimental plot — the encounters of Nicholas with Madeline, the troubles of Kate, and the fate of Smike. At their worst, such plates are incompetent, as in the portrayal of Madeline in "Nicholas recognizes the Young Lady unknown" (ch. 40) (That Browne was aware that he was having trouble with the pose of Madeline is indicated by the several marginal sketches of her figure in the working drawing. The drawing is in DH, and is reproduced in Michael Slater, ed., The Catalogue of the Suzannet Charles Dickens Collection (London and New York: Sotheby Parke Bernet Publications, 1975), P. 47.), or are centered on awkward, melodramatic poses, as in "Nicholas congratulates Arthur Gride on his Wedding Morning" (ch. 54). At their best, they help to sum up the novel's moral themes, as in the designs related to Smike in which the action unfolds in a wooded setting: "The recognition" (ch. 58), and "The children at their cousin's grave" (ch. 65). The latter plate is the last etching in the book and the first appearance of a church since the wrapper, where Ralph Nickleby was seen to be lost to Christianity in a swamp of materialism. Here, the characters are in harmony with Nature, the Church, and with the Christian view of suffering and death as embodied in the story of Smike. It is nothing like what Browne accomplishes by use of frontispieces for summing up the central meanings of a novel (and in this one, a portrait of the author by Maclise is the frontispiece). although the sentimental style returns from time to time, it remains a far less important aspect of Browne's development away from the caricatural than is what we might call the "sequential" mode. The two novels in Master Humphrey's Clock, which follow almost immediately upon Nicholas Nickleby, are special among Browne's assignments for Dickens, and yet they may be seen as preparations for the next novel in monthly parts, Martin Chuzzlewit, in which Browne's debt to and development of the Hogarthian tradition, the "progress" in all its complex manifestations, first really crystallize.

Last modified 23 November 2009