The illustrations for Bleak House are far more uneven in quality than those for the three preceding novels. Most of the comic plates — with a few important exceptions — are technically weak, even sloppy, and many of those which feature the novel's protagonist, Esther Summerson, are relatively uninteresting, though usually done with care. Mrs. Leavis finds Browne's work here "disappointing" because the illustrator "does nothing to actualize the Chancery fog," and there "is little in the way of background and almost no interesting detail," and she decides that in any case illustrations for this novel and those that follow "would have been unnecessary but for the habit of having illustrations," because of the extent to which Dickens' own art had matured (Leavis, pp. 359-60.). Further, she finds those illustrations which do make use of emblematic detail to be inappropriate to Dickens' art, since the "Hogarthian satiric mode" is no longer Dickens' (Leavis, p. 165.). Yet Bleak House contains some of Browne's finest and most complex work in that Hogarthian mode, fully appropriate to Dickens' own effects. Both in combination with and transcending this model the illustrator employs the dark plate technique to convey graphically what is for the Dickens novels a new intensity of darkness. Some of this intensity is retained in the illustrations for Little Dorrit, but in other ways Browne's work for that novel definitely shows a falling-off which is then almost embarrassingly apparent in his last collaborative effort with Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities. [131/132]

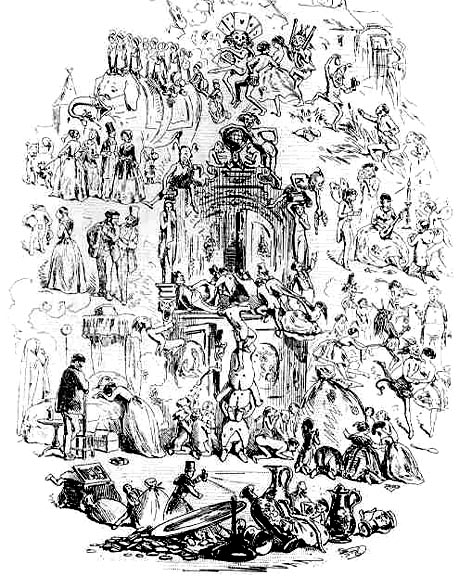

Cover for Monthly Parts, Bleak House illustration 86].

The complexity of Dickens' conception, the many interweaving plot strands and symbolic and thematic parallels of the text, is reflected in some respects from the outset in the complexity of Browne's emblematic conception in the Bleak House monthly cover. Because this design includes a number of identifiable characters, Browne must have had quite explicit directions, or at least some explanation of Dickens' purposes. The novelist had completed the first number by mid-December 1851 , and so could have shown Browne the manuscript (chapters 1-4) well before it was published in March 1852; it is conceivable that Browne saw in addition at least a portion of the second number — which was already in proof, with the illustrations completed, by 7 March — before he finished work on the wrapper design (Johnson, 2: 750.). But three of the vignettes involving specific characters could not have been derived from a reading of the first six chapters, and this together with the fact that the vignettes are connected both visually and in relation to the plot indicates that Dickens explained his intentions in some detail. On the right side of the design we see Lady Dedlock taking a walk beside her carriage (an incident not occurring until Part IV, ch. 12); linked to this panel by a generalized depiction of a young, couple with a distressed cupid between them is a third panel, of Nemo the "law-writer" (actually Captain Hawdon, Lady Dedlock's former lover and Esther's father). although he is mentioned by Miss Flite in chapter 5, Nemo's opium addiction, indicated in the design by an apothecary's bottle on the table beside him, is not referred to until Part III, chapter 10.

These three vignettes together adumbrate the story of Lady Dedlock and Captain Hawdon, estranged in their youth, and now presented in the novel in early middle age. As I pointed out before, there may have been something of a private joke between Dickens and Browne in the fact that the scrivener is called "Nemo," since this was the nom de crayon Browne first adopted as illustrator for Pickwick. Like Browne, the Nemo of Bleak House works at a lowly paid task, hiring out as a free-lance to others, and willing (as Snagsby puts it in chapter 10) to "go at it right on end, if you want him to, as long as ever you like" (p. 95).

The other details in the crowded, though not confused, design relate in unifying theme for the wrapper as well as for the novel. The one way or another to Chancery, which provides the [132/133] notion of Chancery as a gigantic game is expressed by Richard Carstone's remark that it is "wanton chess-playing," the suitors like "pieces on a board" (ch. 5, pp. 41-42). The two other game metaphors employed in the cover are battledore-and-shuttlecock, with lawyers as players and suitors as shuttlecocks, and, across the top of the design, a panoramic game of blindman's bluff, with the Chancery attorneys and officials, appropriately, the "blindmen," and a host of terrified men, women, and children their fleeing victims. The image of the stumbling blindmen suggests that Browne read the first chapter, in which we find "some score of members of the High Court of Chancery bar ... tripping one another up on slippery precedents, groping kneedeep in technicalities, running their goat-hair and horse-hair heads against walls of words" (p. 2). It has recently been shown that the battledore-and-shuttlecock vignette resembles a cut by George Cruikshank for Gilbert à Beckett's The Comic Blackstone (1846) (Tye, pp. 38-41.); despite the resemblance, however, the portrayal of human beings as shuttlecocks goes back at least as far as Gillray, and was used twice by John Doyle ("HB"), in 1831 and 1840. although Cruikshank's cut takes priority as a probable direct source because of its more recent date, many motifs from HB cartoons do turn up in Phiz's illustrations, including the chess game played with human pieces of the Bleak House cover (Copied in this case by Doyle from Retzsch — "HB," Political Sketches, Series 2, No. 509, "Satan Playing at Chess With Man For His Soul," dated 29 September 1837.).

The blindman's bluff image includes at the right a man thumbing his nose at the proceedings, perhaps representing the author's standpoint, or, since he wears shabby clothing, expressing the contempt of a pauper ruined by Chancery toward a court which can do him no more harm. The placement of this vignette at the top puts the most extensive metaphor of Chancery's blindness, incompetence, and random destructiveness in the most prominent position, and also suggests a structural relationship to the rest of the wrapper. Two men, some money, and papers spill over the inside border of the design which is formed of thin sticks acting as an espalier for a grapevine. This vine, winding in and out of the various panels in the wrapper (just as Chancery insinuates itself into life in Bleak House), is evidently barren, a suggestion of the moral sterility of the Court; and the fragility of the supports implies — given the clear hint of collapse in the topmost vignette — that the whole structure is liable to come crashing down, a foreshadowing of the author's warning in chapter 32 [133/134] of the possible spontaneous combustion of the system of govemment and law. (We may recall a similar hint in the structures of ledgers, cash boxes, and playing cards in the Dombey and Son wrapper.)

The only element structurally opposed to the blindmen is the depiction in the bottom center vignette of Bleak House itself and its owner, John Jarndyce; but the prospect is not really a very hopeful one, for Jarndyce, wearing the hat with ear-straps mentioned in chapter 3 (p. 16), has his back turned to both the sinister game above him and the representative figures who surround him. These include a "telescopic philanthropist" embracing two black children; a man blowing a toy trumpet while seated in a cart whose label, "Bubble / Squeak," hints at the commercial bubbles of philanthropic projectors and the squeak of their noise (it also implicitly compares them to the cockney hash); two arguing women; and two fools, one holding a roll of plans marked "Humbug" and another bearing a sign, "Exeter Hall, " the site of evangelical meetings. Jarndyce's habitual denial of the unpleasant is embodied in the weathervane pointing east, representing his defensive fiction that the "wind is in the east" whenever he hears anything distasteful about the philanthropists he supports.

Chancery is represented not only in the game metaphors but in two other vignettes, which together with the chess and battledore images make up the four comers of the inner design. At upper right Mr. Krook the mock Lord Chancellor writes "C R" on the wall for "Chancery Rex," suggesting that Chancery, understood in its broadest symbolic sense, rules modem British society. The corresponding left-hand vignette presents a bewigged man digging up papers with a shovel, which evokes Krook, the collector of papers; we are reminded that Dickens from the beginning conceived of him as the man "who has the papers" resolving the mystery of Lady Dedlock and the case of Jarndyce and Jarndyce (Sucksmith, p. 67.). Finally, just as the suitors pursued by Chancery spill over and threaten to land on Bleak House, so the dirt unearthed by the digging figure spills over its boundaries and seems to descend on Esther's head. To understand this symbol, we must turn to the vignette centering on Esther, perhaps the most puzzling element in the Bleak House cover.

Frontispiece, Albert Smith's The Pottleton Legacy illustration 87].

Esther stands with her face in profile to us, looking down at a fox which assumes a supplicatory or anticipatory position, one [134/135] paw raised; facing Esther is an impish man dancing through a foggy swamp, carrying a lighted lantern in one hand and holding a globe on his head with the other. The globe is a widely used symbol of the material world, and a man bearing it on his head often represents Man burdened down with materialism, although here that is not quite the case. For the lantern and the swamp suggest the will-o'-the-wisp, a prominent emblem used in nineteenth-century graphic art to represent temptation or the pursuit of foolish and self-destructive undertakings (Again, the motif first turned up in John Doyle's Political Sketches, Series 2, No. 150, "A Will o' the Wisp," dated 22 August 1831. Cruikshank also created versions of the emblem but they post-date Browne's own use on the Nicholas Nickleby wrapper.). The two emblems combined in this way imply the temptations of the material world. Phiz had already used the two together in another etching, the allegorical frontispiece to Albert Smith's The Pottleton Legacy (1849), in which the materialistic temptations of the ignis fatuus are made explicit (they had already been implied in the Nickleby wrapper), and a figure nearby bears a globe on his head.

But what of the fox? Recalling the weathervane fox above John Jarndyce may help to clarify matters, for this latter fox points directly to the one standing alongside Esther. It has been suggested to me (by Professor Irene Tayler, in conversation.) that the weathervane fox crystallizes Jarndyce's irritation with his society, and thus in a sense, like the East Wind, represents him. If this is so, then the fox next to Esther may be a kind of protective figure, guarding her against the world (symbolized not only in the globe but in the dirt being shoveled down upon her by the Chancery figure). Moreover, one possible reason to make this protective animal a fox is its conventional association with prudence; in emblem books foxes are often shown listening at the side of a frozen river to see if it is safe to walk upon the ice (I know of no other use of this emblem by Browne, nor have I noted it in Cruikshank or his contemporaries. The animal is identifiable as a fox in this illustration (rather than the "wolf" at the door which Miss Flite speaks of) by its bushy tail.).

The range and complexity of emblematic representation of the novel's themes are considerable in the Bleak House cover, and it should be remembered that the novel's original readers were confronted with this design — and thus were confronted with a visual summary of the novel's thematic concerns — once a month for nineteen successive months. Whether or not a reader took in all the details, he could hardly escape the wrapper's points made about Chancery in the three game metaphors, nor the position of John Jarndyce in the novel. The wrapper's design also hints at the past relationship between Lady Dedlock and the law-writer, an obvious reference when viewed with hindsight. While Bleak [135/136] House's wrapper may not be the most unified in strictly visual terms, iconographically and structurally it complements Dickens' own achievements in the most emblematically unified of all his novels, in which Chancery, fog, mud, disease, and Tom-All-Alone's act as powerful organizing images.

After this promising start, the series of etchings begins weakly; the one attempt at fog, in "The little old Lady" (ch. 2), is puerile, and only with "The Lord Chancellor copies from memory" (ch. 5) does Phiz hint at the power of his best plates in this novel. In terms of plot sequence, the action depicted here is completed only at the end of the tenth part, with Krook's death in "The appointed time" (ch. 32), in which the junk dealer's black doll (of the earlier plate) appears to be shocked at the event. But in its ominous quality, "The Lord Chancellor copies from memory" also foreshadows the dark plates of the novel's second half. Phiz has taken his cue for most of the details from the text, but he adds a demonic mask which reminds us of Miss Flite's remark that Nemo was said to have sold his soul to the devil (ch. 5, p. 40). The Lord Chancellor's pointing finger introduces a motif which will occur more importantly twice again, as we shall see; and Esther's almost completely hidden face, in this and the two preceding plates, is also a motif — one might almost say an emblem — which continues through the novel and links Esther visually with her mother.

Before discussing the long series of illustrations which connect Esther, Lady Dedlock, and some of the novel's themes, I want to take up the four plates in which Browne employs ![]() Hogarthian techniques with the greatest variety and force. Among the novel's sinister, grotesque, or comic figures, there are a number whom Browne seems to handle unenthusiastically. Mrs. Pardiggle, the Smallweeds, Tulkinghorn and Bucket, for example, are given nothing like the vividness and individuality of Phiz's Pecksniff, Gamp, Dombey or Bagstock. But these deficiencies seem to me more than made up for by the inventive handling of Turveydrop, Chadband, and Vholes, three characters who embody the corrupt qualities of Bleak House society: dandyism, false religion, false politics and law. Phiz shows his full powers only beginning in Part V, dated July 1852, when he is between

[136/137]

assignments for Lever, having completed The Daltons in March or April; he will not begin The Dodd Family Abroad until September. (He had also been engaged on Ainsworth's Mervyn Clitheroe until March 1852, and worked on Smedley's Lewis Arundel during both 1851 and 1852, so it is understandable that he may have felt a bit tired and overworked at the start of Bleak House.)

Hogarthian techniques with the greatest variety and force. Among the novel's sinister, grotesque, or comic figures, there are a number whom Browne seems to handle unenthusiastically. Mrs. Pardiggle, the Smallweeds, Tulkinghorn and Bucket, for example, are given nothing like the vividness and individuality of Phiz's Pecksniff, Gamp, Dombey or Bagstock. But these deficiencies seem to me more than made up for by the inventive handling of Turveydrop, Chadband, and Vholes, three characters who embody the corrupt qualities of Bleak House society: dandyism, false religion, false politics and law. Phiz shows his full powers only beginning in Part V, dated July 1852, when he is between

[136/137]

assignments for Lever, having completed The Daltons in March or April; he will not begin The Dodd Family Abroad until September. (He had also been engaged on Ainsworth's Mervyn Clitheroe until March 1852, and worked on Smedley's Lewis Arundel during both 1851 and 1852, so it is understandable that he may have felt a bit tired and overworked at the start of Bleak House.)

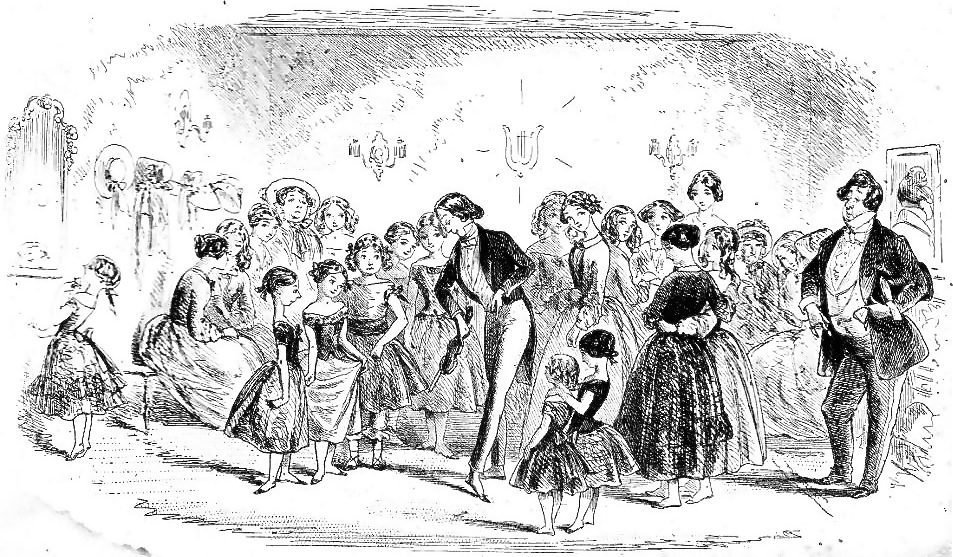

The Dancing School [illustration 88].

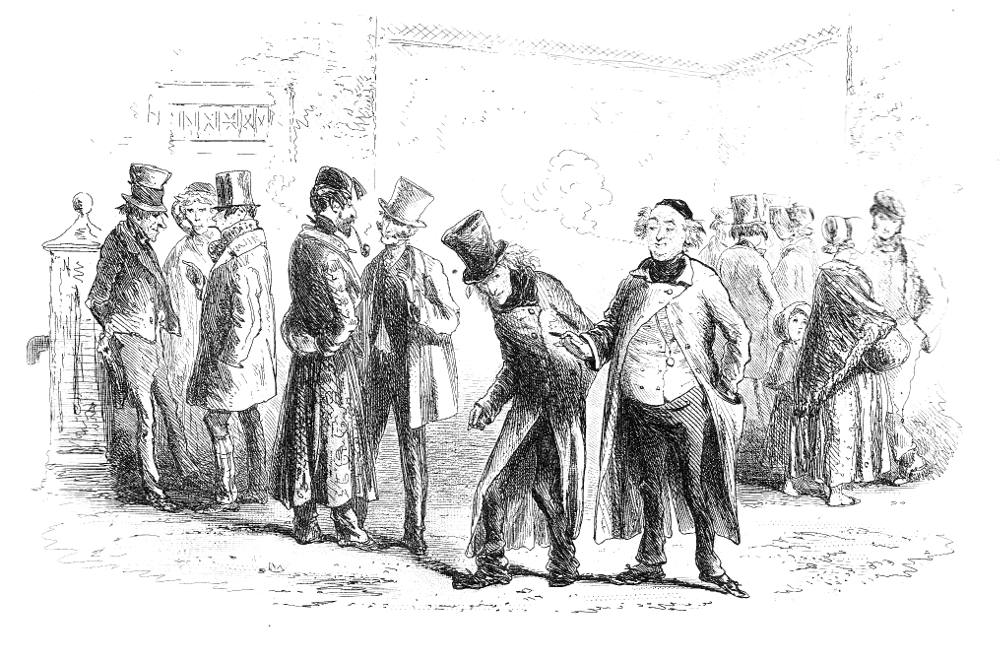

"The Dancing-School" (ch. 14) is the second of fourteen horizontal plates in Bleak House; with its long, sweeping dance floor and its twenty-five distinct figures the plate requires all of the unusually large space allotted to it. Stylistically it is in the mode of some of the best plates for The Daltons and The Dodd Family Abroad, though surpassing in satirical impact anything in Lever's novels. There is relatively little modeling (though some careful shading) in the faces of the characters, but the figures are carefully balanced and arranged (e.g., Prince Turveydrop's pupils form a diagonal from the smallest at left to the tallest at right, with the dancing master in the center), and the lines are controlled. The most significant aspect of the characters' placement involves two mirrors, one at either end, on parallel walls, Into one a very small pupil on tiptoe is barely able to gaze and admire her pert little face; in the other the back of Mr. Turveydrop's ornately styled coiffure (wig) and his spotless collar are reflected. just as the chapter is entitled "Deportment," so this plate really focuses on the Master of Deportment, who stands taller than any other figure and oversees the labors of his son as though he somehow deserves credit for them. Mrs. Leavis' argument that Dickens becomes his own illustrator is given some credence by the marvelous description of Mr. Turveydrop, "a fat old gentleman with a false complexion, false teeth, false whiskers, and a wig" (ch. 14, p. 135); Browne can convey little of this in the mode in which he works.

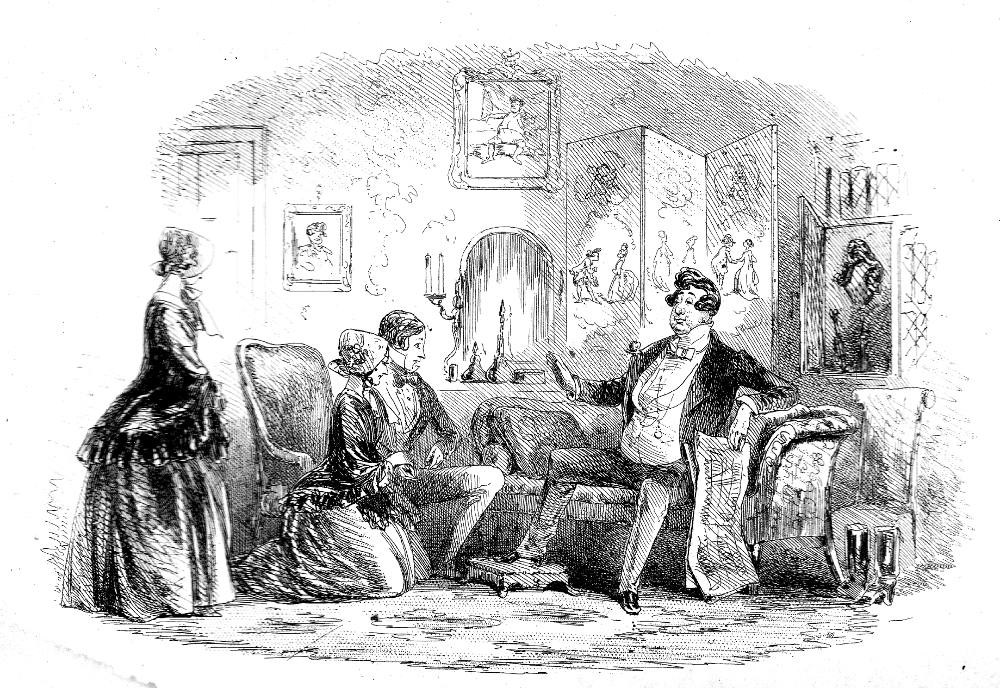

A model of parental deportment [illustration 89].

But the illustration's function is a different one. Apart from the way its composition emphasizes the relative pretended and real positions of father and son, the plate comments upon Turveydrop's narcissism by paralleling him with the vain little girl; and it also unobtrusively makes visible the connection between Mr. Turveydrop and the Prince Regent, his supposed model, referred to early in Esther's meeting with him. Esther feels that he sits "in [137/138] imitation of his illustrious model on the sofa," (1 have not located with certainty the print Esther refers to, but it could be Doyle's "A Political Riddle," Political Sketches, Series 1, No. 21, dated 6 June 1829.) and Mr. Turveydrop recalls when "His Royal Highness the Prince Regent did me the honour to inquire, on my removing my hat as he drove out of the Pavilion at Brighton (that fine building), 'Who is he? Who the Devil is he? Why don't I know him? Why hasn't he thirty thousand a year?'" (ch. 14, p. 137). A comparison of the Model of Deportment in this plate with an engraving by George Cruikshank of King George IV at the beginning of his reign will make it clear that Phiz is consciously using an old device from the days of "6d plain, 1/-coloured" political and social prints, the parodying of a well-known portrait to suggest a parallel between a contemporary and a figure from the past (Portrait of His Most Gracious Majesty George the Fourth, dated 1821, engraved by G. Maile).

It is especially interesting that the Cruikshank portrait — to my eye almost a caricature, though apparently intended to be taken straight — shows George IV standing with the Royal Pavilion in the background. The reference to a print of the Regent on a sofa is less easy to pin down, but it may enter into a later illustration by Phiz, in which Mr. Turveydrop's connection with the Regent is explored in far-reaching ways. That Dickens was reminded of the early nineteenth century's most famous British object of caricature is suggested by his note to himself in the number plan for the dancing school chapter:

Mr. Chadband "improving" a tough subject [illustration 92].

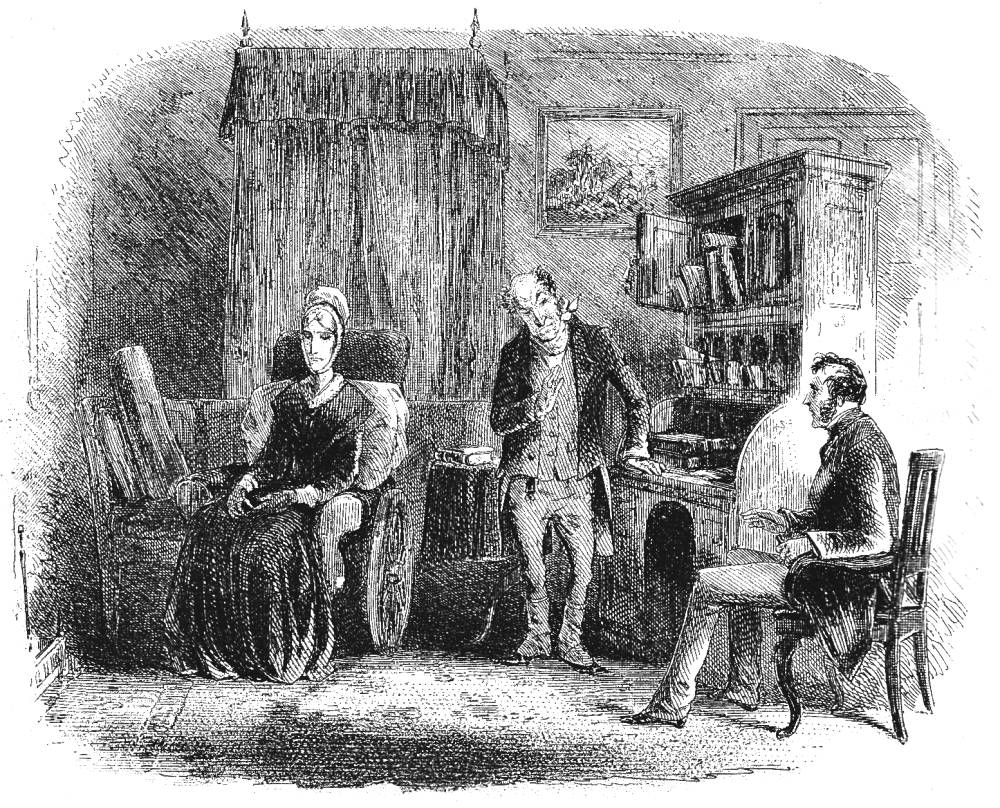

The graphic allusion to George IV in "The Dancing-School" is picked up again, this time solely in illustration, in Part VIII. although this number, comprising chapters 22 through 25, contains many important serious episodes — such as Richard's decision to give up the law for the army, Jarndyce's request that Richard and Ada call off their engagement, Gridley's death, Mlle. Hortense's offer of herself to Esther as a maid, and Jarndyce's gift of Charley Neckett to Esther for that same purpose — Browne was directed to illustrate two scenes notable for their acid, grotesque comedy: "A model of parental deportment" (ch. 23), and "Mr. Chadband 'improving' a tough subject" (ch. 24; Illus. 92). [138/139] A glance at the two plates will reveal a connection between them which could hardly have been missed by those who read the novel in parts, when the two would have been placed together at the opening. although no parallel between Turveydrop and Chadband is made explicit in the text, such a parallel is obvious in Phiz's depiction of the two men: each, with right hand raised, is in the process of bestowing what Esther calls "benignity" (ch. 23, p. 232) upon an assortment of followers and skeptics; in each plate a pair of true believers and a single doubter are similarly placed, Esther facing Turveydrop and Snagsby facing Chadband from the extreme left, while Caddy and Prince kneel close to the Model and Mrs. Snagsby and Mrs. Chadband sit near the "oily vessel." (The drawing for "A Model of parental deportment" (Elkins) is much like the etching, but it is reversed and lacks the details on the screen; that for "Mr. Chadband 'improving' a tough subject" (Elkins), also used for transferring the design to the steel, is rather different from the etching: Chadband, instead of standing upright, is somewhat bent over, his right arm raised, but his left pointing at Jo, who faces the opposite way. The change in Chadband's position makes the parallel with Turveydrop much more evident. As usual, we have no way of knowing who originated the change, but since the drawing had been used for transferring it seems plausible that the original had already been approved by Dickens, and Phiz made the changes on his own. The drawing for this plate is reproduced in Kitton, Dickens and His Illustrators, fac. p. 92.) Other details link these two etchings with "The Dancing-School": the mirrors of the earlier illustration have their counterparts in both plates, and the lyre decorating a wall of the dancing school is repeated in miniature on a chest in the Chadband illustration.

The broad significance of the parallels seems clear. Turveydrop and Chadband are just two characters who embody the theme of hypocrisy and false belief, but these two are linked by the special blatancy of their use of others' faith in them as a means to the gratification of selfish desires; yet without the graphic parallel one's impression might be that these fat men are merely two among a miscellany of grotesques who come off and on stage like music-hall performers. And there are at least two other graphic links between the illustrations, for each character is mirrored or parodied by a picture on the wall near the top center, and at the right hand of each there are upon a table objects which emblematize the character's major preoccupations. But further, the presence of such details is related to Browne's knowledge of his forerunners in graphic satire, and their special significance can best be inferred by examining those sources.

King George IV as the Prince of Wales by George Cruikshank [illustration 91].

Few of the qualities usually associated with George IV as king or as prince regent are brought out in Dickens' treatment of Turveydrop; of the "First Gentleman's" licentiousness, gambling, drunkenness, gourmandizing and foppery, only the last two are present in his fictional emulator, and only the foppery is given much emphasis. Yet when we trace the derivation of old Mr. Turveydrop's image we find that the artist, has subtly retained in attenuated form some stereotypical Regency qualities in the [139/140] Model of Deportment. The immediate source appears to be George Cruikshank's wood engraving of George IV as Prince of Wales, "Qualification," the first illustration to William Hone's pamphlet, The Queen's Matrimonial Ladder (1820), which traces the course of the Prince's marriage to Caroline of Brunswick up to the year of his accession to the throne (The pamphlet appears to have been immensely popular. It was perhaps the cleverest and best-illustrated satire of the Regent/King to have been published, and Browne might easily have seen a copy.). Despite the obvious differences, these two pictures contain three notable visual similarities: the position of the torso and legs of each figure; the almost identical placement of the head of the Prince and that of Turveydrop in front of a decorated tripartite screen; and the presence of similarly shaped objects upon a table near each figure's right arm.

But before going into these parallels, we must complete the derivation by going back to the source of Cruikshank's malicious caricature, Gillray's already sufficiently cruel portrait of the same man, "A VOLUPTUARY under the horrors of Digestion" (July 2, 1792; BM Cat 8112) (M. Dorothy George identifies Cruikshank's cut as an "adaptation" of Gillray's etching — see BM Cat, X (1952), p, 78.). Not only are the poses in the two caricatures nearly identical, but Cruikshank picks up details from Gillray and either repeats or alters them tellingly. In both designs empty bottles are piled beneath the Prince's chair and a dice box and dice are in evidence. But one of the upright decanters in Gillray is replaced in Cruikshank by an overturned and presumably empty bottle, while the dishes of mutton bones are replaced by two candles, burnt down to their holders and guttering — signifying the burning out of the Prince's life as the empty bottle suggests both repletion and exhaustion. although Gillray in other prints frequently dealt with the Prince's notorious amours, this aspect is adverted to in his "VOLUPTUARY" caricature only by the bottles of nostrums for venereal disease; the artist was probably planning the ironically contrasting print which appeared a few weeks later, "TEMPERANCE Enjoying a Frugal Meal" (July 28, 1792; BM Cat 8117), in which the King and Queen dine on eggs and sauerkraut amidst emblems of miserliness, and he thus would have wished to emphasize gluttony in the first etching of the pair. But Cruikshank in his adaptation gives full play to lechery, showing on the screen Silenus upon an ass, a winged goat, and three voluptuous women (parodies of the Three Graces) dancing around a satyr's effigy, while a woman's [140/141] bonnet hanging on a corner of the screen further intimates the Prince's main interest.

Where Cruikshank replaces the evidences of gluttony with emblems of a lecherous and spent life, Phiz in turn adorns Mr. Turveydrop's dressing table with implements of this character's main obsession, adornment of self: a mirror, and bottles of cosmetics which resemble in shape the candlesticks of Cruikshank's cut. In the Chadband plate, the corresponding table holds a dish of food, a decanter, two glasses, and an open Bible — together emblems of a gorging and preaching vessel (to use Dickens' terms). But there is another technique of iconographic expression in both plates which hints that Dickens' illustrator had in mind not only Cruikshank's caricature of the aging Prince, but its source in Gillray. Above the Prince's head in the Gillray is a portrait of Luigi Comaro, "the author of ... a discussion of disciplines and restraints which might be exercised in pursuit of longevity" (Hill, p. 163). The irony of this allusion is paralleled in the companion satire of George III and Charlotte by an empty frame labeled, "The Triumph of Benevolence," and a picture entitled, "The fall of MANNA."

An ironic contrast of this kind is evident in the picture of John the Baptist directly above Chadband's head; the pose of the figure is similar to Chadband's, but nothing could be more pronounced than the contrast between Chadband's overfed and well-clothed body and the gauntness and rags of St. John (and of little Jo). The corresponding portrait in the "deportment" plate reflects Browne's sources even more directly. It appears to show Mr. Turveydrop as a younger man, scarcely less obese, but more luxurious and indolent in pose; in view of Esther's reference to the print of the Regent on a sofa, this may be intended for the Gillray original rather than the Cruikshank copy which shows an aged Regent in spite of its purporting to depict the Prince of Wales. In either case this picture, like that of John the Baptist, parallels the technique of contrasting portraits in Gillray's print; but there is enough resemblance in dress and pose between Turveydrop and the Cruikshank, and between the portrait and the Gillray, to suggest that Phiz may have been thinking of both caricatures. To parallel further his own Turveydrop plate with [141/142] the Chadband one is to further imitate his own imitation of Cruikshank's imitation of Gillray — clearly, Browne was aware of his artistic heritage.

We may approach the interpretative significance of Browne's allusion by considering first what he makes of the folding screen, Cruikshank's bacchic and priapic emblems are transformed to decorous courtiers, ladies, and cupids, an attenuation of sexuality which is in line with Trevor Blount's view of Turveydrop as a "dehumanized neuter" (pp. 149-65); Blount also stresses parallels between Turveydrop and Chadband). I think there is even more to it. Desexed as he may be, Turveydrop is not wholly asexual, as witnessed by the way Esther shrinks from his tribute: "'But Wooman, lovely Wooman,' said Mr. Turveydrop with very disagreeable gallantry, 'what a sex you are!'" (ch. 14, p. 138). Beneath Mr. Turveydrop's impotent exterior lurks the remnant of a nasty sexuality which is emphasized by knowledge of Browne's graphic sources. There is also a possible parallel between the Model of Deportment's mistreatment of his late wife and the mistreatment popularly imputed to the Regent in regard to Caroline of Brunswick — the subject to which The Queen's Matrimonial Ladder is devoted. Ironically, while the middle and lower classes abhorred the Regent, by contrast in Bleak House two of the best, gentlest souls, Prince Turveydrop and Caddy Jellyby, blindly believe in Deportment. Thus in a sense the dandyism Dickens excoriates in the novel as typical of the upper classes has also infected the humbler orders of his age.

The parallel to Mr. Chadband suggests that this oily individual represents another case of the same thing — the deluding of the lower middle classes through a form of Christianity which is essentially no different from the religion of Deportment. Three details provide further comment on the specious preacher. Immediately beneath his outstretched arm and imitating its angle is a toy trumpet, which suggests that Chadband is blowing his own tinny little horn, like the self-puffer on the cover design. Above the chimneypiece are two symbols which suggest the spuriousness of Chadband's religious pretensions: a fish, one of the conventional symbols for Christ, is preserved under glass, but its mouth is open and its eyes regard Cbadband with astonishment. And on the mantel itself a human figure resembling Jo huddles under a bell jar; on either side are shepherd figures with sheep. [142/143] These elements represent the isolation of Jo from pastoral aid, the traditional church being indifferent to him and the pseudo-clergyman Mr. Chadband preaching at him for self-aggrandizement rather than out of compassion.

This series of three plates, from the dancing school to Chadband is, as an example of Browne's use of the Hogarthian techniques of allusion, emblematic detail, and visual parallel between illustrations, on a level of artistic and interpretative accomplishment with the title page of Martin Chuzzlewit, the etching which shows Edith Dombey's final confrontation with Carker, and the first plate of David Copperfield.

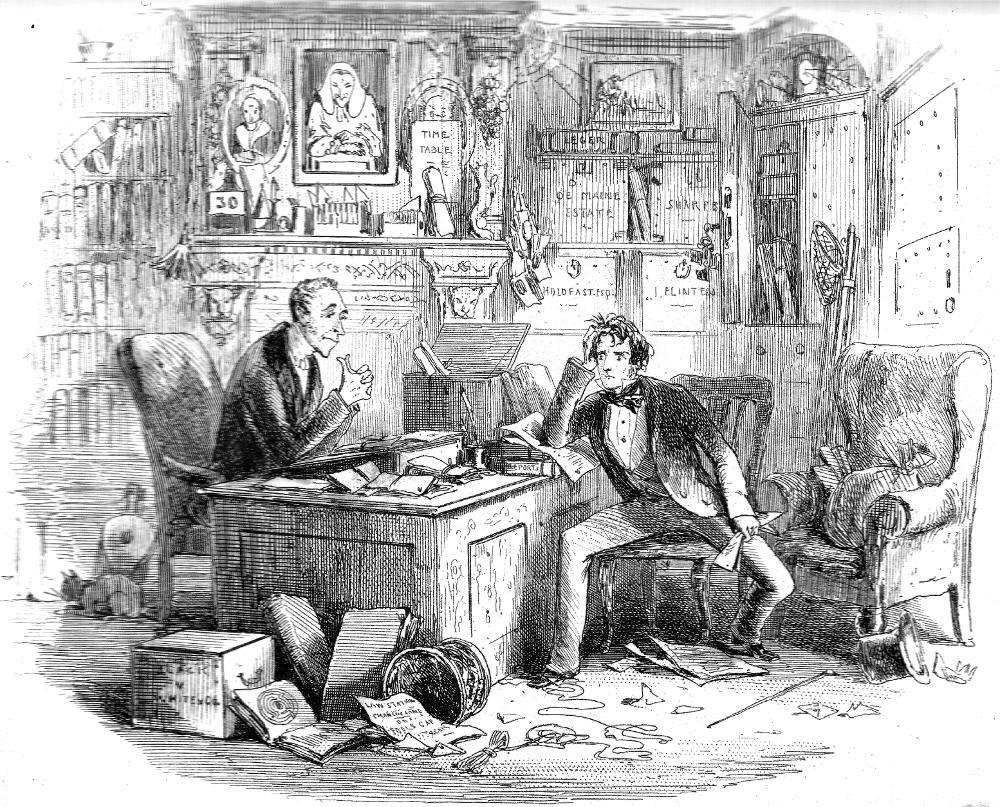

Attorney and Client: fortitude and impatience [illustration 93].

In the depiction of Mr. Vholes, the eminently respectable solicitor for whose parasitic survival the archaic procedures of Chancery must be maintained, Phiz indulges in his last big splurge of emblematic invention for Dickens. The techniques of "Attorney and Client, fortitude and impatience" (ch. 39) are perhaps less brilliant than those of the Turveydrop-Chadband series, but a close examination of this etching's details and process of creation reveals much about one aspect of Phiz's art.

Q. D. Leavis has criticized this Vholes-Carstone plate on the grounds that it depicts Mr. Vholes in terms of a "Hogarthian satiric mode" which is no longer Dickens', and that Phiz "conveys nothing of the sinister ethos that emanates from Mr. Vholes in the text of the novel." (Leavis, p. 360.) Mrs. Leavis' assumption is that the only proper function of illustrations like Browne's is to mirror the import of the text, but, as I have shown, an illustration may present a point of view and bring out aspects which are not overtly expressed in the text. Mrs. Leavis also fails to differentiate multiple purposes in Dickens. In describing Vholes's office, Dickens himself employs Hogarthian techniques, first conveying the decay and dirt, the "congenial shabbiness" of Symond's Inn, and then the "legal bearings of Mr. Vholes." The office is described in detail worthy of Hogarth, and then the narrative takes another turn and speaks of the "great principle of English law," i.e., "to make business for itself' (ch. 39, p. 386). Throughout the page-long discussion of the 'Wholeses," Dickens uses metaphors which border on the emblematic: the law is a "monstrous maze," Vholes and his tribe, cannibals, and the [143/144] lawyer is "a piece of timber, to shore up some decayed foundation that has become a pit-fall and a nuisance" (p. 386). In the interview with Richard, Dickens describes some blue bags stuffed in the way "the larger sort of serpents are in their first gorged state," while the office is "the official den" of predators (P. 387). And most Hogarthian of all, and a detail which turns up in the illustration, "Mr. Vboles, after glancing at the official cat who is patiently watching a mouse's hole, fixes his charmed gaze again on his young client" (p. 388).

Two preliminary drawings for Attorney and Client: fortitude and impatience [illustrations 94 & 96].

One can hardly blame Phiz for picking up this last detail as well as that of the maze, and elaborating these conceits into a multiplicity of images representing the predatoriness and confusion of the law; and there is nothing discordant between this elaboration and Dickens' own treatment. The three extant drawings indicate that Browne took a good deal of trouble with this plate. One, which I think is the earliest (Illus. 94), shows Vholes at his desk much as in the ultimate etched version, but the desk is open beneath, and thus not the kind which would echo hollowly like an empty coffin (specified by Dickens). Richard stands with his back to Vholes, tearing his hair (as on page 387); even at this stage, most of the emblematic details are clearly visible, indicating that they were a part of the original conception. In a second drawing, the figures are placed as in the final version, but the details are somewhat sketchier and Phiz apparently was dissatisfied with Vholes's face, which is much less predatory in this version; another head, more like the one in the previous drawing, is sketched in the margin (This drawing is in the Berg Collection of the New York Public Library, and is reproduced in Szladits, p. 131.). The drawing which was used for transferring the subject (Illus. 96) is much like the etching, only rather sketchy, and the head of Vholes is still not like the final one, which seems to come from the first drawing.

The significant details are so numerous that in order to discuss them coherently it seems best to divide them into three broad categories:

1. Emblematic representations of the law's confusion and delay. These include a prominently displayed page of an open book showing a maze, a reference to Chancery and the Jarndyce and Jarndyce suit that echoes the text; a clock covered with cobwebs, suggesting the endless delay of the law and of Mr. Vholes's work [144/145] for his client; a box of papers labeled "De Maine Estate," probably a pun on demain; and a skein of what is doubtless red tape, which stretches in a tangle on the floor and around the foot of the law's victim, Richard Carstone. The latter detail could also fit into a second category,

2. The predatoriness of the law and its effects upon its victims. Taking off from the textual detail of the cat and mousehole, Phiz includes a mortar and pestle (recalling Tom Jarndyce's remark, related by Krook, that being a Chancery suitor is like "being ground to bits in a slow mill" — ch. 5, p. 38); a snuffer and candle, suggesting Richard's rapid physical decline, a bellows, probably referring to the inflaming effect of Chancery, particularly as Weevle remarks to Guppy about Richard that "'there's combustion going on there ... not a case of Spontaneous, but ... smouldering combustion'" (ch. 39, p. 391); and an ornamental pair of foxes reaching after grapes, a metaphor for the perpetual frustration of suitors. The paper at bottom center, reading "Law Stationer / Chancery Lane / Fools Cap," may refer to Richard's reduction to the state of a fool by Chancery. More specifically symbolizing Vholes's predation are a spider's web with a fly about to be caught in it, a net and fishing rods, a picture of a man fishing, and two lion heads on the fireplace. (Some of these emblems have already appeared elsewhere in Browne's work, most recently in "The Money Lender" in Roland Cashel, in which spider's web, net, and fishing tackle, as well as a fly trap and stuffed fish, are present.)

3. Direct representation of the law. Most prominent is the portrait of a judge with his spectacles off, whose eyes look quite blind; a time table, recalling the delays in Court; and several boxes of papers for various cases, whose names are clearly emblematic: "Black v. White," an ironic comment on the fact that. Chancery cases are never clear-cut; "Holdfast, esq"; "I Flint, esq"; and "Sharpe," all alluding to the tenacity, greed, and heartlessness of Chancery suitors and, especially, attorneys.

Dickens and Browne evidently wished to overwhelm the reader with the sinister qualities of Chancery and Vholes, and the Hogarthian method was the simplest and most efficient way to accomplish this. Dickens in the text of chapter 38 sets an [145/146] example for his illustrator, and it is pointless to object that Phiz has not captured all the qualities of Dickens' portrayal of Vholes in one etching.

The Vholes-Carstone illustration is not typical of the plates in the second half of the novel; of the last seventeen illustrations, ten are dark plates, and these are foreshadowed by two plates done with ordinary techniques in the first half. "The Lord Chancellor copies from memory" is linked to "Consecrated ground" (ch. 16) not only by its darkness but by the pointing hands of Krook and Jo, and the presence in the first of Esther and in the second of Lady Dedlock, each with her face mostly or fully hidden. Krook points at the letter "J" which he has just written, referring to Esther's connection with Jarndyce, while Jo points at the grave of Lady Dedlock's lover — in total ignorance, but the episode will involve him unwittingly in Tulkinghorn's pursuit of Lady Dedlock's secret. As J. Hillis Miller has remarked, Dickens clearly intended a connection between the pointing "Allegory" in Mr. Tulkinghorn's chambers — which will eventually point to his corpse when Lady Dedlock is the prime suspect for his murder — and Jo's pointing hand, for in the number plan he wrote, "Jo — shadowing forth of Lady Dedlock at the churchyard./ Pointing hand of allegory-consecrated ground / 'Is it Blessed?'" (Miller, p. 70; Sucksmith, p. 70.) "Allegory" is introduced in Part III, chapter 10, but its pointing hand is not mentioned until Part XIII, ch. 42, just after Hortense has threatened Mr. Tulkinghorn, although in its first appearance it is "staring down at his intrusion as if it meant to swoop upon him" (p. 92). This distant "shadowing forth" shows how consciously Dickens planned what might be called the emblematic structure of the novel; in this particular case, while he has certainly prepared the reader for "Allegory" playing a significant role, the connection between one "pointing" in chapter 16 and another in chapter 42 is perhaps too distant to be effective, particularly when the visual parallel is not completed until Part XV, chapter 48.

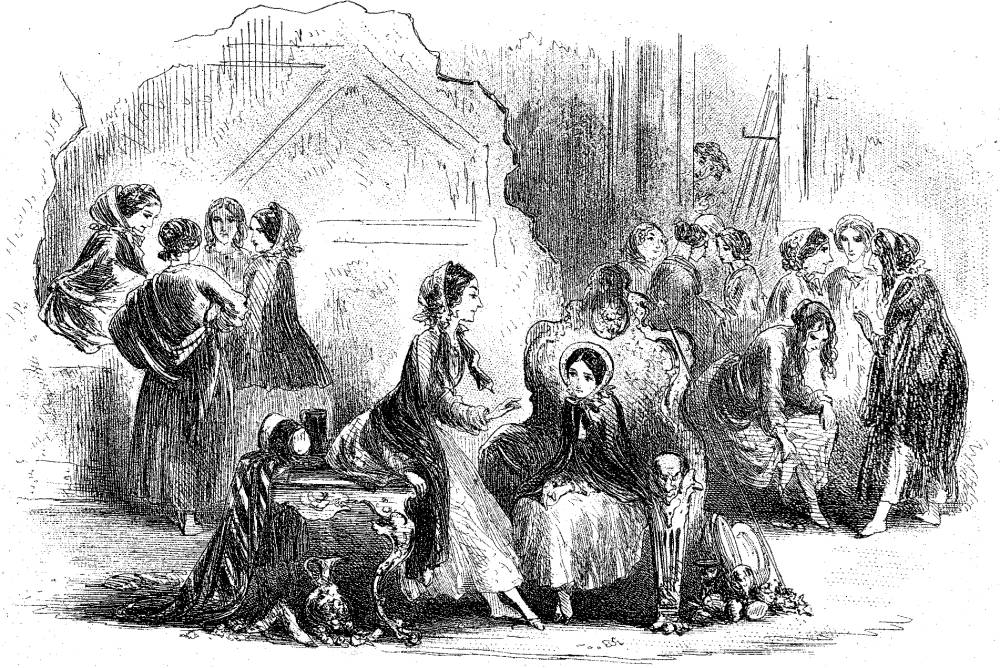

Esther and her mother see one another for the first time at a distance in the part following the graveyard episode, and here, in "The little church in the park" (ch. 18), Browne interprets the social role of the Dedlocks and its relation to the Bleak House world by means of several of his customary techniques. The [146/147] overall scene recalls the Norfolk parish church, and the London church in which David is married in David Copperfield; not only is the cycle of life represented but so are various attitudes toward the hymn singing, from participation to boredom. The congregation is also divided between the lower gentry or middle class in the main pews, the servants from the manor in a pew behind the great one, the tenants standing in the aisle, and the party from Mr. Boythorn's cottage in his pew at some distance from the pulpit, while the Dedlocks seem to rule the entire scene from above in the great pew. But this dominance is undercut by a set of incidental details: in what may be a coincidental — but nonetheless effective — parallel to the third plate ("The Lord Chancellor copies from memory") in which, following the text, a pair of large, broken scales is shown, here an emblematically unbalanced pair of scales of justice is seen over the head of a life-size memorial effigy of a judge in robes and wig who bends over a law book; propped behind his robes a tome labeled "Vol. 30" hints at the law's interminability. This effigy is behind the Dedlocks' pew, implying a connection between the injustice of the Chancery world and the aristocratic "dandyism" of the Dedlock world.

But another possible reason to have this figure intrude on the space of the complacent and isolated Dedlocks is to imply that even as impervious in their magnificence as they seem, the Dedlocks will be judged, either in this life or the Hereafter. For such would seem to be the message of two inscriptions: "Easier for a camel" (above the Dedlocks' heads) indicates that their wealth may thwart chances for salvation, and "All shall be changed" (directly opposite them) suggests that the social arrangements visible in the congregation and assumed by Sir Leicester to be permanent will be altered. A memorial inscription, "Patient Grissle," above the Boythorn pew, makes one think of Esther, as the long-suffering woman who will eventually be righted, though here of course it is not a husband but a mother who has caused her suffering; Browne may have had in mind only Esther's patient endurance, without thinking through all of the implications. Lady Dedlock herself is perhaps alluded to in the rather fuzzy but still legible carving on the pulpit of Eve and the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, recalling her temptation and fall in early life. Above the whole scene, however, is a [147/148] shield with "Semper Virens," reminding one of the possibilities of forgiveness and eternal life. Taken together, the details strengthen the fundamental point of the scene: the first encounter, alive with possibilities of revelation and change, of Esther with her mother.

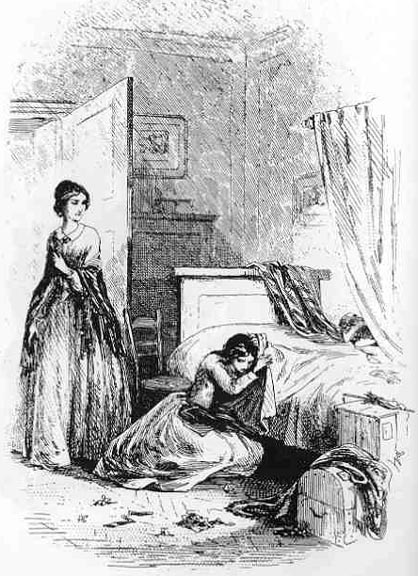

Esther's next encounter with her mother, in the illustrations, is in the second half of the novel, and although the etching is rendered in the ordinary mode it can be said to initiate the long series of dark plates. "Lady Dedlock in the Wood" (ch. 35) and "The Ghost's Walk" (ch. 36) are linked, occurring in the same chapter and forming a continuum in Esther's experience — the revelation of her mother's identity leading to her feeling of terror at the Ghost's Walk and at the idea that it is she "who was to bring calamity upon the stately house" (ch. 36, p. 362). The contrast of tone and mood between the two plates is notable. The first is structured by means of the tree under which Esther sits, which divides the space into three sections with one figure (Lady Dedlock, Esther, and Charley) in each. Phiz has been careful to dress Esther and her mother so that they appear very much alike, and Esther's face is hidden. It is here that the motif of the hidden face becomes most evident; this episode follows Esther's recovery from smallpox and in the illustrations her scarred face will remain hidden throughout. The text implies that Esther's illness is a kind of symbolic retribution for Lady Dedlock's crime of sexual waywardness, for Esther divests herself of her lifelong guilt feelings only after the illness and the encounter with her mother. Simultaneously, Lady Dedlock takes on a new and greater guilt, which can only be resolved through her death. From the point of this confrontation onward not only is Esther's face always hidden in the etchings, but her mother's is as well, silently implying a parallel between the two women, between Esther's scarring and Lady Dedlock's guilt. (Phiz apparently had no text to read, since an early but quite finished drawing [Elkins] shows Lady Dedlock walking toward her from the distance; Dickens probably provided inadequate directions and then realized upon seeing the drawing that it would have to be redone.)

Browne's reserving of the dark plate technique until the novel is more than halfway done proves to be an effective strategy, since it groups the dark plates together and restricts their special [148/149] force (with one partial exception) to depicting the tragedy of Lady Dedlock. Like five others of the ten dark plates in this novel, "The Ghost's Walk" has no human figures (two others have only tiny and barely discernible ones); this is not typical of Browne's dark plates either for Dickens or for other novelists, and the effect here is to accentuate the novel's emphasis upon external, nonhuman or dehumanized forces as the dominant agents in man's life in society — Chancery, Parliament, Telescopic Philanthropy, Law, Disease. Without the special technique, "The Ghost's Walk" might not even be a very good illustration: lacking the varied dark tones that give the sky itself an ominous effect, the large proportion of empty space would unbalance the composition. The "grotesque lions" (ch. 36, p. 361) are, as details in a drawing, puerile, but the contrast of darkness with the white highlights saves them froni being, ridiculous.

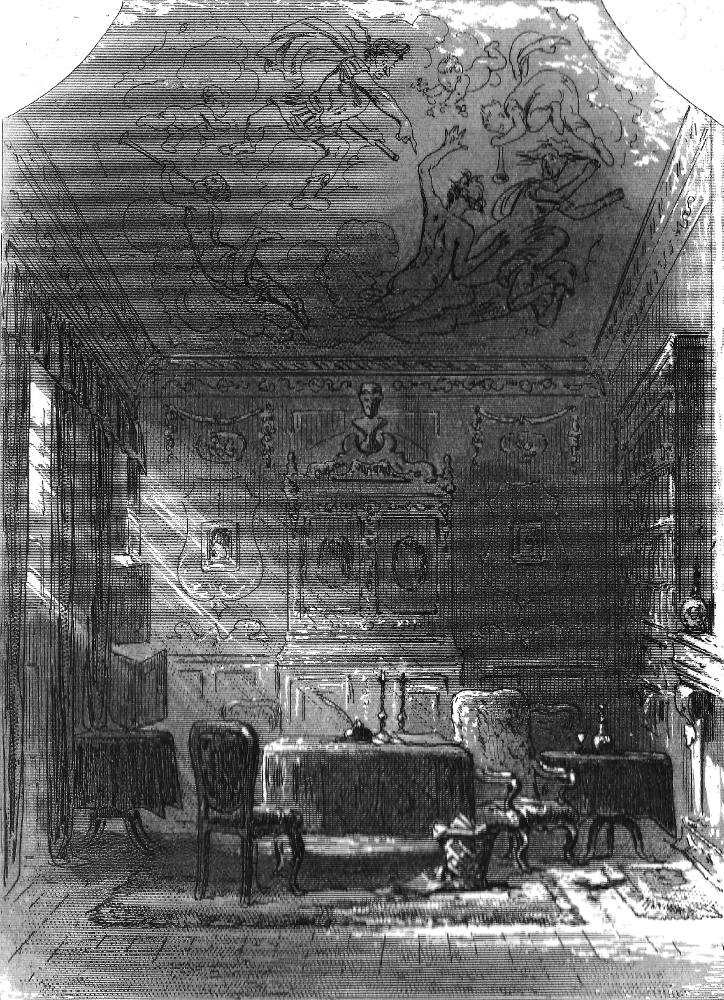

Two preliminary drawings for Sunset in the long drawing-room at Chesney Wold [illustrations 96 & 97].

The theme and tone of "The Ghost's Walk" are picked up in the next part, in "Sunset in the long Drawing-room at Chesney Wold" (ch. 40; Illus. 96 and 97), which makes graphically more explicit the doom hanging over Lady Dedlock. At first glance the plate seems to have been executed by a totally different method than its companion in Part XIII, the Hogarthian confrontation of Richard Carstone and Mr. Vholes, for the dark plate technique gives it a powerful quality of depth, and the lack of human figures contrasts with the caricatural content and emblematic devices of the preceding plate. As John Harvey has pointed out shadow upon Lady Dedlock's portrait, stressed in the text (ch. 40, p.398). is in the illustration so subtly combined with the other shadows that the viewer only gradually recognizes its presence and menace (Harvey, p. 155.). So strong are the effects of tone, perspective, composition, and the feeling that nonhuman forces are in control, that one is liable to overlook the fact that this illustration convevs its thematic emphases by means of methods as emblematic as those of its companion plate. Dickens provides in his text the central emblematic conception by dwelling upon the threatening shadow that encroaches upon the portrait of Lady Dedlock, and this in turn becomes the subject of the plate. But Phiz has added a central emblem, a large statue which gives the plate a focus distinct from the portrait and the shadow, and which complements them. It depicts a woman seated with a winged infant leaning upon her knee and looking up at her. In general terms [149/150] this probably embodies the idea of motherly love, but its likely source in Thorwaldsen's sculpture of Venus and Cupid makes it possible to be more specific: in Thorwaldsen's piece, Venus is consoling Cupid for the bee sting he has just received, and the application at this stage of the novel would be not only to Esther's parentage, but to Lady Dedlock's failure to mother her, and to prevent her suffering as a young child.

The idea of nurture and protection is carried out further in the small ceramic of the Good Samaritan, while the ornamental doves represented as drinking from the bowl nearby may reflect further the theme of nonerotic love (Thorwaldsen's group of Venus and Cupid also includes two doves, and I suspect that in his statue, and here, they are meant to de-eroticize the god and goddess of sensual love). The fan on the floor and the nosegay and shawl on the chair may indicate the recent presence of Lady Dedlock, but the guitar with its broken string must be emblematic, signifying loss as in David Copperfield. All of these emblems quietly introduce thematic emphases which would be maudlin if included in the text; since the drawing room is realistically done, and nothing in it seems out of keeping with the general style of decoration, only gradually do these emphases enter our consciousness. One other touch may be equally important: a bedroom is discernible at the very rear of the design. It is not clear whose room this is, but would it be too farfetched to associate it with the marriage bed and thus with the Dedlocks' disgrace? In the context of the second plate to the next monthly part it mav take on an even more sinister meaning, as I shall suggest (Two drawings survive: one, reversed and indented as usual (Elkins), contains all the details, though some are sketchy and the drawing as a whole — in charcoal — is a bit fuzzy; the other (Gimbel) is in pen and wash, not reversed, and almost certainly a preliminary drawing, since it contains neither guitar, nosegay nor fan. Once again, I hypothesize that left-right orientation was important for Browne in this plate.).

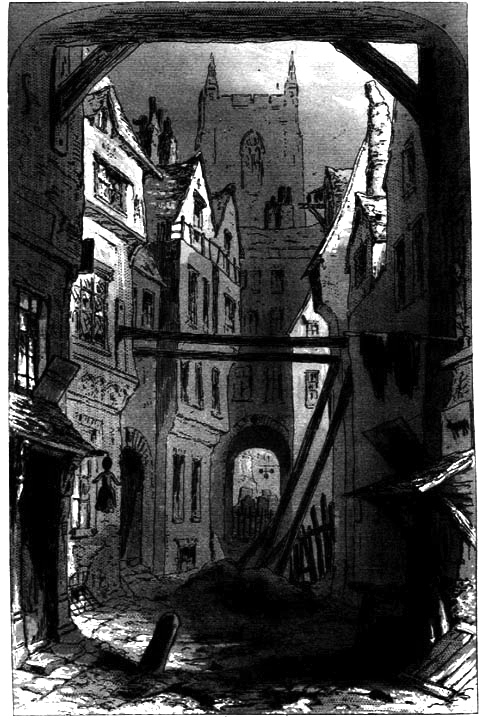

Tom all alone's [illustration 98].

"Tom all alone's," (ch. 46) perhaps the best known of all the dark plates, is what I have in mind. although we lack Dickens' instructions, there is evidence pointing to its owing a good deal in conception to Hogarth's Gin Lane, probably by way of the novelist's own knowledge of that engraving. Comparing Gin Lane to Cruikshank's temperance works in the Hogarthian tradition, Dickens had in 1848 suggested its relevance to his own time: the engraving emphasizes the causes of drunkenness and crime in the way it "forces on the attention of the spectator a most neglected, wretched neighborhood ... an unwholesome, indecent, abject condition of life." Dickens quotes Lamb to the effect that "the very houses seem absolutely reeling," but that this as [150/151] much implies "the prominent causes of intoxication among the neglected orders of society, as any of its effects." The church whose steeple is seen in the distance "is very prominent and handsome, but coldly surveys these things, in progress underneath the shadow of its tower ... and is passive in the picture. We take all this to have a meaning, and to the best of our knowledge it has not grown obsolete in a century" (Cruikshank, 1: 158.) Some three years later (in a speech to the Metropolitan Sanitary Association), Dickens spoke of the certainty "that the air from Gin Lane will be carried, when the wind is Easterly, into May Fair" (Fielding, p. 128.) Both the East Wind and the theme of the inevitable infection of all classes consequent upon the neglect of the lowest are of course central to Bleak House, which he was to begin a month later. And explicit mention of this theme turns up in the passage the plate is designed to illustrate: "There is not a drop of Tom's blood but propagates infection and contagion somewhere" (ch. 46, p. 443).

When we look at Browne's version of "Tom" in this context, the connections with Hogarth seem inescapable. Here again, but even more prominently, we have a church tower passively overlooking a scene of degradation; here too, the buildings are in danger of collapsing and are held up by wooden supports. But whereas in Hogarth's picture human beings are central, in "Tom all alone's" they are absent; while Hogarth's composition gives a sense of chaos, Browne makes his composition as symmetrical as possible, so that the contrast between the visual repose afforded by the wooden supports in the middle of the picture and what we know to be their function is ftill of irony and tension. Most startling of all, Browne has framed the upper edge of the plate with a horizontal brace between two houses so that the very sky seems to be held up by this untrustworthy support, a brilliant way of underlining the relation between the condition of Tom-All-Alone's and the rest of society. In this regard the plate is reminiscent of the Bleak House cover, in which all of society is in danger of being brought down by the weight of Chancery. Through the arch at the rear we can see into the churchyard which, like Gin Lane, includes the pawnbroker's three balls, symbol of decline into poverty; presumably Esther's father has been buried in that filthy place. But what is most fascinating about this plate — and surely not accidental — is that the churchyard holds the same relative position in the composition as the bedroom in the "Sunset" [151/152] plate. Hence a subtle connection is made between the liaison of Esther's parents, the Dedlock marriage bed, and the churchyard where Captain Hawdon lies and where Lady Dedlock will die.

A preliminary drawing and the final plate: A new meaning in the Roman [illustrations 94 & 96].

Not only are these two plates linked, but connections are also made backwards to "Consecrated ground" and forwards to "The Morning," with the same churchyard visible through the gate at which the corpse of Lady Dedlock lies. But the earliest plate showing the churchyard also forms links with another dark plate, "A new meaning in the Roman" (ch. 48). I have already questioned the visual effectiveness of the connection between two such distant illustrations (one appearing in chapter 16 and the other in chapter 48) but the fact is that the pointing of Jo is more vividly brought out in the illustration than in the text. An additional difficulty in tracing the process of Dickens' thought about these parallels and his transmission of them to Browne is suggested by the evidence of a shift in Dickens' mental picture of the Roman "Allegory." Initially, the figure painted on the ceiling is described as "sprawling" (ch. 10, p. 92), and Browne's first version incongruously combines pointing with sprawling; evidently Dickens had Browne correct this excessively comic conception. The final version, with its imposing male figure pointing at the scene below, manages to make "Allegory" every bit as silly as the text suggests, by juxtaposing three figures who flee in terror with three or four (in 29B and 29A respectively) jolly cherubs strewing flowers and blowing trumpets in the direction of the frightened figures. The dark plate technique is used tellingly, with a contrast between extremely dark shadows — the details nonetheless visible in them — and beams of sunlight coming in the window. As in other dark plates the only human figures are effigies. Phiz has also included the decanter of wine and a glass, to remind us of the buttoned-up Tulkinghorn's only real pleasure in life.

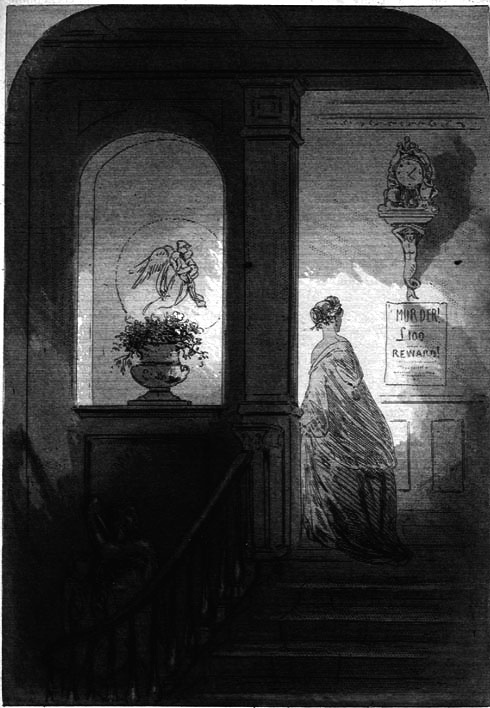

Shadow [illustration 101].

The immediate consequence of the murder, Lady Dedlock's increasing sense of guilt, as though she had committed that crime, and her preparation for flight, are depicted and summed up emblematically in "Shadow," which is paired with another plate whose caption, "Light" (ch. 51), seems intended to suggest a link. although Richard Carstone's decline in the toils of Chancery, the subject of "Light," and Lady Dedlock's impending flight do belong to separate strands of the plot, [152/153] within Dickens' scheme they are in fact thematically related. Both individuals are seen as victims of their society's inhumane codes and institutions, yet both share some of the responsibility for their plight. The irony of the seemingly antithetical captions is that the plates are not really in contrast: "Light" refers only to Esther's sudden realization that Ada and Richard are married, and that Ada is devoting herself to him wholly in his decline; and the halo of light surrounding the couple sets off more starkly the hopelessness of Richard's condition. Visually, the illustration is linked to its companion through the figure of Esther, nearly central in the composition and with a hidden face, like Lady Dedlock in "Shadow." The latter caption refers back to the symbolic shadow encroaching upon her portrait, and here the shadows are closing in, so that only a portion of Lady Dedlock's figure remains in light.

The primary subject of "Shadow" is, ostensibly, Lady Dedlock's impression that she is sought for the murder of Tulkinghorn, for she is looking at the reward poster. But three emblematic details broaden the range of reference. Thorwaldsen's "Night," repeated from the stairway plate of Dombey, shows a motherly angel carrying aloft an infant, recalling Lady Dedlock's failure to be a mother to Esther and her consequent guilt and self-torment. The "murderous statuary" of the text is specified by Phiz as a sculpture of what appears to be Abraham and Isaac at the point when Abraham is about to sacrifice his son but is stayed by the voice of the Angel of the Lord. Such a detail appears in the form of a print on the wall in A Harlot's Progress, III, where, Ronald Paulson suggests, it may allude to the contrast between God's and man's justice (p. 36.). This contrast is certainly relevant here, and the possible allusion as well to Hogarth's fallen Moll is not entirely beside the point. But in addition, the idea of death being prevented by God relates to the fact that Lady Dedlock's child, whom she had thought dead, also has been spared. The third emblem is a clock above Lady Dedlock's head, in its particular position perhaps indicating that her time has run out; it is decorated below with an ominous mermaid, a detail which has some connection with the possible reference to Hogarth's "lost" woman. We may recall Thackeray's use of the mermaid as a simile for Becky Sharp — the creature's slimy tail submerged in the murky depths having to substitute for any detailed discussion [153/154] of what Becky was actually doing in those disreputable days on the Continent after Rawdon had left her. (The relevant passage is in chapter 64 of Vanity Fair.) The implication for Lady Dedlock would be that her hidden, sexually sinful past is about to be revealed (The similarity to the mermaid clock in Sketches of Young Couples in the plate, "The old Couple" is not very strong — the latter clock has no threatening aspect, and is primarily a Cupid and Psyche design.).

The next step in Lady Dedlock's flight is represented by an extraordinary dark plate, "The lonely figure" (ch. 56). If ever Hablot Browne succeeded in expressing the essence of a text it is here, in his depiction of

the waste, where the brick-kilns are burning with a pale blue flare; where the straw roofs of the wretched huts in which the bricks are made, are being scattered by the wind; where the clay and water are hard frozen, and the mill in which the gaunt blind horse goes round all day looks like an instrument of human torture; — traversing this deserted blighted spot, there is a lonely figure with the sad world to itself, pelted by the snow and driven by the wind, and cast out, it would seem, from all companionship. [p. 544]

The possibilities of the dark plate are evident, first of all, in the way the snowflakes have been done, through the stopping-out of tiny bits so that above the relatively even tone of the ruled lines they appear to be in front of the subject, between the viewer and the rest of the etching. although the "pale blue flare" cannot be captured, Browne has given the kilns on the horizon hovering, ominous shapes, rather like Mexican pyramids. The image of the mill as a torture device is achieved by placing the shaft, with its straps for the horse, so that it points directly at the fleeing figure of Lady Dedlock. A detail not in the text, hut which Browne is said to have made a special visit to a lime pit to get right, is the device for crushing lime, a contraption of huge spiked wheels, attached to a frame to be pulled by a horse (Kitton, p. 107). It is placed at the top of a rise above Lady Dedlock and appears to threaten to descend and crush her. Even the three piles of bricks in the right foreground look like strange predatory animals, while the precarious board bridges across the pits suggest the danger of the path that the lonely figure is taking.

The first pair of dark plates within a single part, "The Night" (ch. 57) and "The Morning" (ch. 59), have captions which remindus of "Light" and "Shadow," but Browne apparently was confused about which was which, since on the paired proofs in the [154/155] Dexter Collection the penciled captions are reversed, and there is a note from Browne, "Which is 'Night' of these subjects?" Such confusion is understandable in view of the darkness of both subjects, and it suggests that Dickens did not always take Browne fully into his confidence by explaining the sequence of the plates and what they represent. Both are effectively in keeping with the dark tone of the novel. The narrative is indefinite about exactly where Bucket spots the brickmaker's wife disguised as Esther's mother, except that they first drive through a riverside neighborhood and then see the woman as they cross a bridge. The etching shows Westminster Abbey in the background, at an angle which suggests that this is where Millbank turns into Lambeth Bridge. The Abbey here has much the same connotations as does the parish church in "Tom all alone's," implying the church's isolation from human suffering.

"The Morning" is still darker in tone, and the more heavily bitten of the two steels (36A) is rather muddy, even in an exceptionally good impression. But the other steel is better: though startlingly dark, in a good impression the gravestones are possible to make out with a putto visible on one stone, a skull on another (as in "Consecrated ground"). although these could not literally be the ones in the earlier illustration, an iconographic connection is made. This dark plate does center on a human figure, but it is still comparable to those which lack such figures because Lady Dedlock's corpse has been reduced almost to a thing by Browne's treatment of it as part of a pattern of light and shade — although her hand can be seen reaching through the bars of the graveyard gate, an important thematic emphasis. Browne has reached a stage in his own art where he seems to find it more and more fascinating to experiment with the possibilities of form, tone, pattern, and structure, and this could contribute to the de-emphasis of human figures; yet although many of the dark plates for other novels demonstrate similar aesthetic concerns, they never again, within a single work, appear so devoid of recognizable human figures.

The four plates for the final, double number were executed as usual according to the novelist's directions; a letter survives which indicates that instructions for Part XVIII, and those for [155/156] Part XIX-XX, six in all, were dispatched to Phiz from Boulogne within a few days of one another, which implies that Dickens had this group, at least, planned out in advance as a kind of sequence (Browne, pp. 292-93.). It is thus conceivable that the dark plate technique and the dehumanized subject matter were specified by him. Only one illustration in the double part pertains directly to any action in that part: "Magnanimous conduct of Mr. Guppy" (ch. 64), which is handled economically and with somewhat more life than the other conventionally comic plates. "The Mausoleum at Chesney Wold" (ch. 46) corresponds to a passage which remarks that although some of "her old friends, principally to be found among the peachy-cheeked charmers with skeleton throats," said that "the ashes of the Dedlocks ... rose against the profanation of their company" by the presence of Lady Dedlock, in fact "the dead-and-gone Dedlocks ... have never been known to object." But the etching conveys nothing of this irony, being an atmospheric dark plate of a rather static kind, which includes the trees which "arch darkly overhead," but omits the owl "heard at night making the woods ring" (ch. 46, p. 519). Its rather grim aspect does not fit very well with the hopefulness of the novel's conclusion, although it may have been Dickens' intention to have it represent reconciliation and peace. That Phiz found the subject excessively sober is indicated by the working drawing (Elkins), in the margin of which he has sketched three mocking devils, one thumbing his nose with both hands, one laughing directly at the mausoleum, and the third peeking around the border of the drawing with a smirk on his face. How Dickens felt if he in fact saw this drawing we cannot know, but his doubts about Browne, expressed at least as long before as Mrs. Pipchin, would not have been lessened by it.

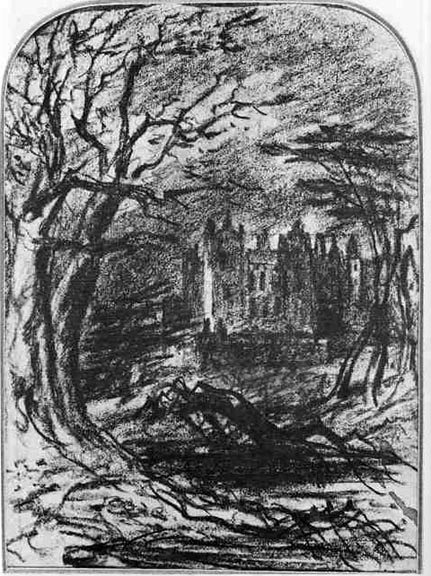

Working drawing for Frontispiece, Bleak House illustration 102].

The frontispiece and title page, although published originally with the two plates just discussed, were planned with their ultimate position at the opening of the bound edition in mind. The frontispiece shows the manor of Chesney Wold in the distance, evidently at such time as "the waters are out in Lincolnshire" (ch. 2, p. 6), for the foreground shows — with fine dark plate technique — murky, marshy ground, while the trees are blown about in the wind and the sky is full of dark clouds. The manor itself almost bears the aspect of a haunted house; there is no specific indication that this haziness is meant to convey an [156/157] explicit idea like the fading of the nobility, but the effect of the etching — for me, anyway — is one of ambiguous unpleasantness: loneliness, sterility, the lack of human connection are all suggested. The charcoal working drawing is itself quite different in tone from either steel, having been done with free, broad lines, but it is equally effective in its spooky way.

As a complement to the manor, the small title page vignette shows the opposite end of society — urban humanity in its lowest aspect. The subject is taken from chapter 16 (pp. 156-58), the first description of Jo the crossing-sweeper, and the comparison between the conditions of boy and dog in which the narrator argues that the "brute" is in most respects "far above the human" (p.158). In the background, to add a touch of urban squalor, Phiz has drawn tiny figures of two ragged women quarrelling, with a shabby man watching idly. In the context of the novel, the coiltrast between these two etchings emphasizes the indifference of the powerful classes toward the powerless, but also conveys the feeling that the former, especially the nobility, are to be associated with death, the lower classes with life. The original appearance of these plates with those of the Dedlock mausoleum (in the double part) surely strengthens the point.

We mav now frame some replies to Mrs. Leavis' general conlplaints about the Bleak House illustrations. True, Browne (toes not capture the sense of fog and nnid so important in the text; but the dark plates create an atmosphere coinplenientary to that of the text, especially in the literally dark and dehumanized plates depicting "Tom all alone's," "A new meaning in the Roman," "Shadow," "The lonely figure," "The Night," "The Morning," and the mausoleum and manor of Chesney Wold. In such illustrations, oppression, confusion, and the power of dehumanized institutions are evoked as effectivelv as in the symbolic fog of the text. Dickens truly has achieved new heights through the use of new techniques in Bleak House, but his reliance on "Hogarthian" devices has by no means vanished, and they actually appear in certain sections more heavily and emphatically than before. Thus Browne's use of emblematic devices is, again, complementary, and sometimes conveys meanings which might be mandlin or too glaring if included in the text itself. This complementary process operates one way in the Turveydrop and [157/158] Chadband plates, which introduce a complexity of satiric allusion that would be difficult to achieve verbally; while it works another way in the drawing-room plate, which combines tonal subtlety with an emblematic statement of themes not made explicit in the text.

One need not attribute the apparent laxness of some of the more conventional plates to Browne's deterioration as an artist; rather, his interests seem to have shifted, so that much of the time the mere portrayal of characters does not engage his energy and he is more concerned with the arrangement of structures, light, and dark in seemingly abstract patterns. In the context of Victorian illustration as a whole, "The Morning," whatever its technical shortcomings, is a much more daring and experimental step than one expects from an illustrator whose role is usually thought of as subordinate to his author's, and subject to his author's will. The contemporary dismay at these etchings gives us a hint as to just how radical a departure it was, and Phiz's willingness to continue such experimentation into the last years of the decade may be evidence of the extent to which he desired to break through the limitations normally imposed on illustrators, as Dickens in his way was breaking through the limits of novelistic realism. A contemporary magazine, Diogenes, published a parody entitled "A Browne Study," which included a supposed illustration of "Lady Dedlock Lamenting Her Happy Childhood." It suggested that the dark plates were nothing more than a way of avoiding proper draftsmanship — see Dickensian, 65 (1969), 144.

A cursory run-through of the etchings for Little Dorrit gives the impression that Browne's excellence in the dark plates is maintained on a level equal to Bleak House, and that many of the regular plates are more carefully rendered than a high proportion of those in the earlier novel. On the other hand, definite lapses of technique are in evidence in some of the conventional plates, and seven of the eight dark plates occur in the first half of the novel; not one of the eight includes a single emblematic detail, consistent with a general reduction in Browne's use of such conceptual techniques. (Such a reduction, already discernible in Bleak House, becomes rapid for Phiz in the latter half of the 1850s, to the extent that by the end of the decade emblematic details have virtually disappeared from his work.) As a group, the Little Dorrit illustrations seem less necessary than those for Bleak House, and yet some enhance the novel, making its "dark" feeling visible, and underlining some of its themes by means of familiar iconographic techniques. [158/159]

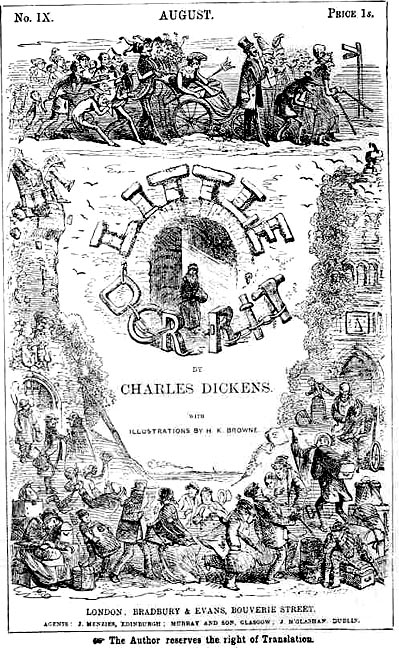

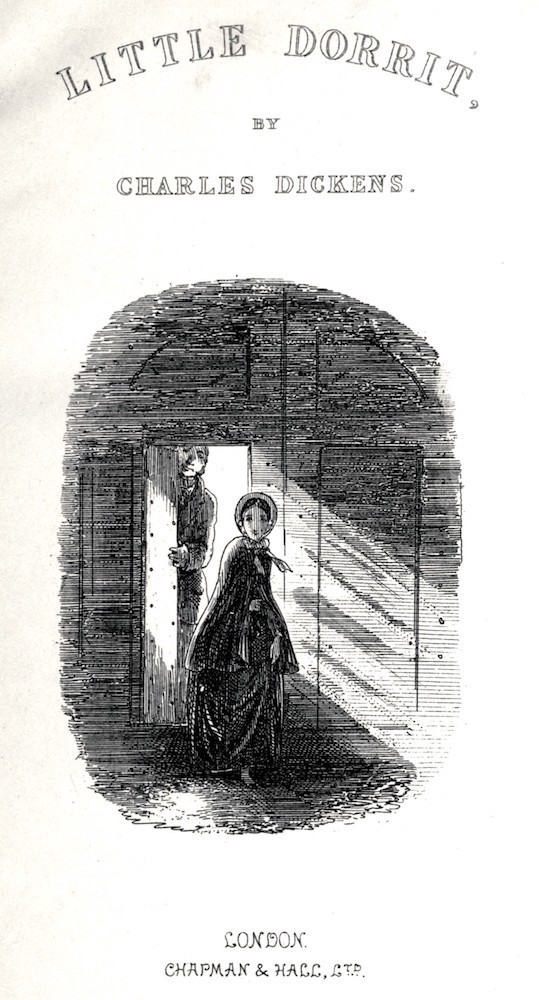

Cover design, Little Dorrit illustration 103].

Like Bleak House, Little Dorrit depends for a great part of its effectiveness upon Dickens' translation of his social vision into symbolic vision: Mrs. Clennam's paralysis, the parasitic Barnacles, Mr. Merdle's banality of evil, and perhaps above all, the motif of the prison. The successes and failures of collaboration depend partly on Dickens' assignment of subject, and partly on Browne's execution of each subject. Like all the monthly serial novels from Nicholas Nickleby onward, this one begins with a cover design intended to embody the novel's main themes; and like Martin Chuzzlewit, Dombey and Son, and perhaps more arguably, David Copperfield and Bleak House, Little Dorrit ends in the monthly parts and thus opens in the bound edition with a complementary pair of etchings that serve both as foreshadowing and retrospective devices. The cover design is more unified than Bleak House's, and quite a bit less specific as to individual characters. John Butt and Kathleen Tillotson discuss this cover in some detail in Dickens at Work (pp. 224-26), but Browne's original drawing was not available to them, and it reveals differences with the final plate which shed some light on the points they discuss. This drawing is part of a set of Browne's drawings for Little Dorrit, formerly in the collection of the late Comte de Suzannet; the set was put up for auction with the rest of the Suzannet collection in 1971, but not sold; subsequently it was stored in the Dickens House. I am grateful to Dr. Michael Slater, editor of The Dickensian, and Miss Marjorie Pillers, curator of the Dickens House Museum, for the opportunity to examine these drawings in 1972, and to the late Comtesse de Suzannet for permission to photograph several of them. Since then, they have been sold to a collector who will not permit their reproduction). First, Butt and Tillotson speculate on whether the original design carries the originally intended title, "Nobody's Fault"; they remark that this would have an ironic effect in connection with the political and social details that are depicted. In fact the drawing bears the published title, executed almost precisely as in the cut, with letters of stone and chain. In the center, Amy Dorrit stands at the outer gate of Marshalsea Prison, just having emerged from within; Butt and Tillotson comment that she stands "in a shaft of sunlight," but do not note that this sunlight — which here, as in the etched title page, lends a sanctified air to Amy — comes from within the prison, and that in a sense Amy goes into a world much darker than the prison. When it is repeated on the title page, this image is in turn complemented by the novel's frontispiece.

The "political cartoon" (as Butt and Tillotson call it) across the top, showing the blind and halt leading a dozing Britannia with a retinue of fools and toadies, is largely the same in the drawing, but one important detail differs in the extension of this motif down the sides of the design, while others are developed more clearly in the actual woodcut. The crumbling castle tower is in the drawing, as is the man sitting precariously on top of it, a [159/160] newspaper in his lap and a cloth over his eyes, oblivious of the deterioration of the building. But while in the cut the church tower is clearly ruined, with a raven (or jackdaw?) atop it, the ruin is less evident in the drawing, and on the tower we have a fat, bewigged man asleep on an enormous cushion; this looks like something out of the Bleak House cover, since the cushion is probably meant to be the woolsack, and the man a high member of the legal profession. I suspect that Dickens told Browne to remove him, as his place on the church is inappropriate. The black bird in the cut would seem to signify the general decay of Victorian society and the prevalence of death, or, if it is a jackdaw, the thievery of institutions; yet I cannot find it any more appropriate to the church. The child playing leapfrog with the gravestones, a concept we have earlier traced back to Browne's frontispiece for Godfrey Malvern, here underlines the theme of indifference and irresponsibility. One other alteration likely to have been at Dickens' insistence is the representation of Mrs. Clennam in her wheelchair, with Flintwinch standing alongside, In the drawing we see instead, from the rear, a woman in a bath chair, pushed by a man. Dickens probably wished to have a more particular representation of Arthur's mother, as she and Jeremiah have a malevolent appearance in the cut and stand out as the only other definite characters, apart from Amy.

Little Dorrit's cover is effective in conveying certain themes — decay, indifference, irresponsibility of government, and confusion — as well as foreshadowing major tonalities of the novel, such as the dark prison, Little Dorrit as central figure, and Mrs. Clennam and Flintwinch as evil genii presiding over the ramifications of the plot. Along with the Bleak House cover it is the most socially conscious of the designs, and presents its ideas more directly than its predecessor. Dickens must have supplied a good deal of direction for this wrapper, given that the date of the following letter (19 October 1855) is approximately six weeks before the publication date of Part 1:

Will you give my address to B. and E. without loss of time, and tell them that although I have communicated at full explanaton length with Browne, I have heard nothing of or from him. Will you add that I am uneasy and wish they would communicate with Mr. Young, his partner, at once. Also that I beg them to be so good as send Browne my present address (N, 2: 698] [160/161]

Left: Title page, Bleak House [illustration 105]. Right: Frontispiece, Bleak House [illustration 104].

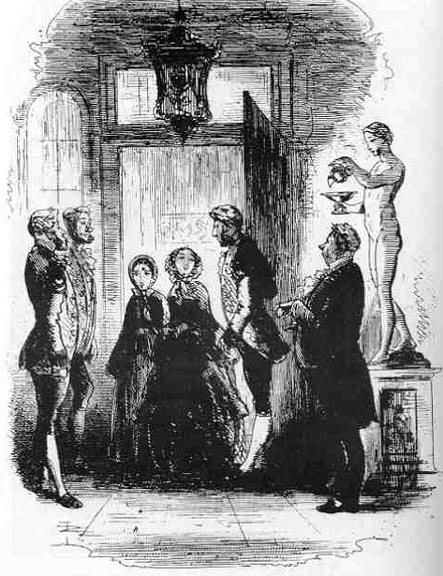

Similar evidence of concern with illustrations is to be found in a note to Browne regarding the last two illustrations for a novel, possibly Little Dorrit (it is undated): "I hope the Frontispiece and Vignette will come out thoroughly well from the plate, and make a handsome opening to the book." (N, 2: 814. I can find no direct evidence that this in fact refers to Little Dorrit, but it is printed in the Nonesuch Letters with other correspondence of the Little Dorrit period.) In this novel they do, the title page echoing the central motif of the wrapper. The implication that the world outside the prison is darker than that within is borne out by the frontispiece, in which the figure of Amy is a virtual mirror image of that on the title; but here she is entering the Merdle mansion with Fanny, and from what we have learned of both Mrs. Merdle and her views on "Society," as well as Mr. Merdle, his crimes, and his suicide, this world is indeed more sinister than that of the prison. Yet in line with Dickens' text, Phiz has portrayed Amy in such a way that she conveys the sense of an innocence so strong as to be impervious to the corruptions of either the Marshalsea or Society; this is less true of her figure in the cover design, where her character has not yet been established and she looks as if she is bowed down with resignation.