This article comes from a copy of the Magazine of Art Vol.VI (1883) in the Internet Archive, contributed to the archive by the Getty Research Institute. The original illustrations have been placed on the appropriate pages (which are given in square brackets in the text), and links have been added to other material in our own website. — Jacqueline Banerjee

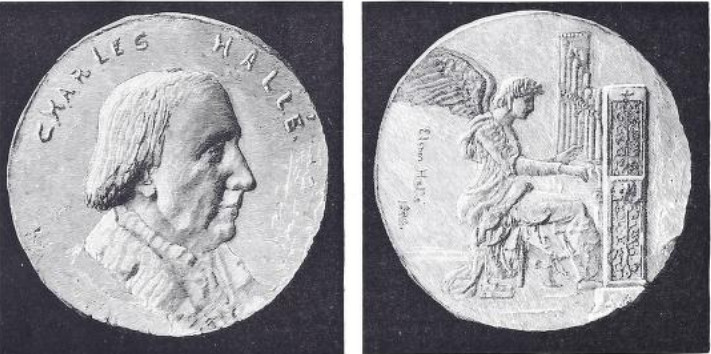

I. Medal of Charles Hallé (by Elinor Hallé).

IT is an undeniable fact that the artistic production of a nation, taken as a whole, is the outcome and expression of its taste and temper. In art, as in other things, the demand creates the supply, and the lower the standard of public taste, the lower will be the quality of the art provided. How far public taste can be cultivated is a very wide question. Could we accept unquestioningly the utterance of a certain gifted author — "The arts are now yielded to the flat-nosed Franks; and they toil, and study, and invent theories to account for their own incompetence," and so forth — little effort would be made towards improvement. But on the Continent the Fine Arts are made a distinct department in the scheme of Government, and ministers are appointed whose special duty it is to foster and promote their interests; while in England there was, until a few years ago, no official recognition whatever of the needs and [324/325] claims of the Fine Arts. A painter, remembered more by his misfortunes and untimely end than by the attainment of his artistic ideal, but whose honest enthusiasm and sound judgment in the cause of art education caused him to be unceasing in his efforts to induce the Government to interest itself in this matter, wrote:— "Professors of Art at the Universities are as much needed as Schools of Design'" These words have now achieved fulfilment, and the writings and lectures of Haydon, no less than his personal efforts, have doubtless helped to promote the object so near his heart.

The Government have provided Schools of Design all over the kingdom, and at the three chief English Universities a chair of Fine Arts is established. These latter, however, are due neither to the solicitude of an art-fostering Government, nor the combined convictions of academic dons. The munificence of an enlight ened and public-spirited private individual, Mr Felix Slade, has made it possible to maintain a course of lectures on the Fine Arts at Oxford and Cambridge Universities; while in London, owing to a difference in the terms of his bequest, a school has been established for practical instruction, presided over by a professor who is himself an artist.

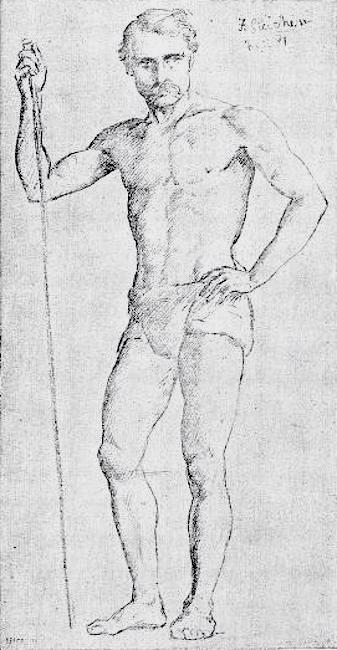

II. Study in red chalk (by Miss A P Burd).

The Slade Schools have from the first taken up an independent position as regards the method of instruction pursued. Mr. Poynter, the first appointed Slade Professor at London University, came, as it were, to virgin soil. Bringing to his task a practical acquaintance with the Continental methods of teaching, as well as with those of the Royal Academy and South Kensington Schools, and having a strong conviction of the evils existing in the latter, he set to work to graft the good of the French method on to the foundation of the English. I remember listening to Mr. Poynter's inaugural address in the large life room of the new schools, in October, 1871, in which he explained the principles on which he proposed to direct the work of the students. Here, for the first time in England, indeed in Europe, a public Fine Art School was thrown open to male and female students on precisely the same terms, and giving to both sexes fair and equal opportunities. And it is to the precedent then established that ladies have since elsewhere had the necessary advantages for study placed within their reach.

In 1880 the north wing of University College was enlarged to meet the growing wants of the students, of whom there are now a hundred and forty. In Mr. A. Legros an able and competent successor to Mr. Poynter was found: one well fitted to carry on the intelligent system of instruction already instituted. But Professor Legros did more than this; he struck out in a line of his own, and his "demonstrations" if they may be so called, are among the most popular and useful characteristics of his teaching. Not content with saying to his pupiils, "Do as I tell you" he occasionally takes brush or pencil from their hand and says, "Do as [325/326] I do." It is an exemplification of the old saying, "An ounce of practice is worth a pound of precept." Not only when going from easel to easel, to correct the students' work, does he sometimes pause and complete a study, the other students grouping round and watching; but on stated occasions a special model is ordered, and the Professor, standing in the centre of the life school, paints a complete study-head before those students who are sufficiently advanced to be admitted to the life class. His method of work is simple in the extreme; the canvas is grounded with a tone similar to the wall of the room, so that no background needs to be painted. With a brush containing a little thin transparent colour the leading lines and contour are touched in; with the same simple material the broad masses of shadow are put in, then gradually the flesh tones are added, the half-tones and lights laid on, the highest lights being reserved for the last consummate touches.

In about an hour and a half, sometimes in less time, the study is completed, and the watchers have probably learnt more in the course of that silent lesson than during three times the amount of verbal instruction. It will perhaps be asked whether Professor Legros wishes his students to paint their studies in as short a time as himself? whether they may not be tempted to imitate the quickness and dash, rather than by patient plodding study to acquire the certain facility of the master-hand?

III. Study in red chalk (by the Countess Helena Gleichen).

Against this there is no surer safeguard than the watchful eye of the Professor and his as¬ sistants. Work that aims at being pretty rather than correct, which is showy when it ought to be thorough, which is hasty when it should be careful, calls forth the unqualified blame of the master, and is, in fact, held up to public obloquy. Ever ready to recognise talent and encourage industrious, honest work, even where no great talent exists, Professor Legros wages incessant warfare against all attempts at pseudo-mastery in his students' work. On the other hand he does require a certain amount of rapidity in what they do. The system of elaborate "stippling" and manipulation which allows the student to take a mental "nap," whilst his hand is busy with bread and point, is not suffered. What is asked is an intelligent representation of the model or cast, with special reference to action, light and shade, tone and general correctness of drawing; and, before the student can relapse into the above-mentioned mental drowsiness, a fresh model, pose, or cast is put before him, a fresh combination of light, shade, and tone is presented to him; so that his energies are constantly being called into action and kept in exercise steadily. The fact that more is learnt in making several drawings of various figures, in various positions, than in elaborating on one drawing from the same point of view, is quite obvious.

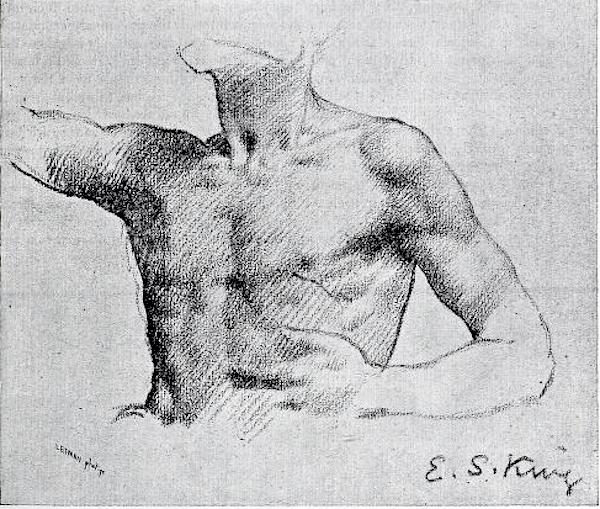

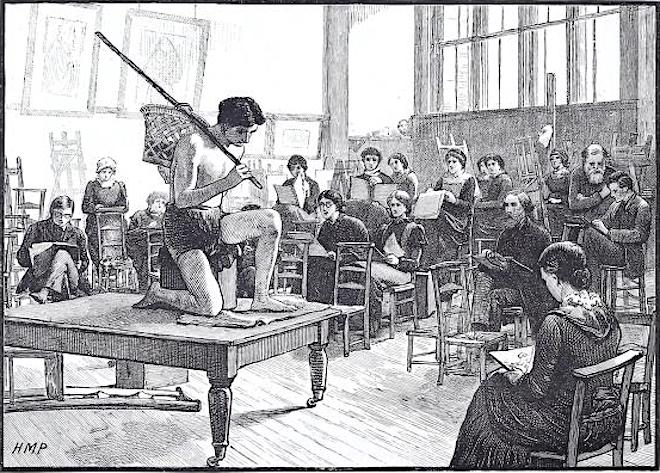

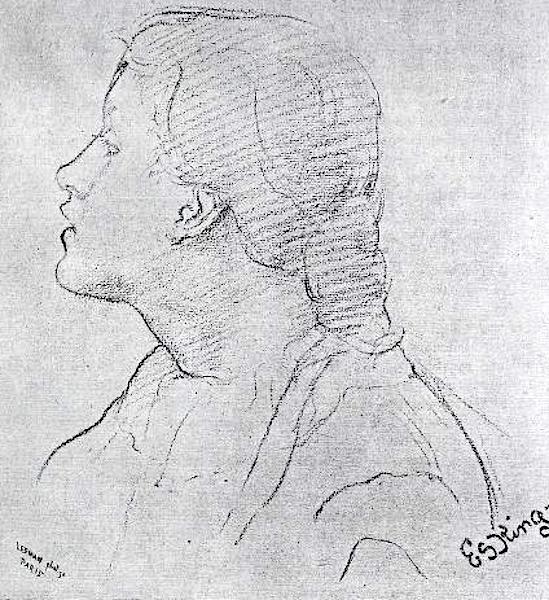

It will be interesting to examine more closely the daily routine. Although no competitive test of proficiency is required from a new student on entering the schools, the Professor examines the previous work of the applicant for admission, and relegates her either to draw or paint from the antique or from the flat, as he considers best for her. In like manner every promotion from one stage of study to another is referred to — and controlled by — the Professor. Autotypes from drawings by the Old Masters are sometimes given to the students to copy; and [326/327] this excellent practice, combined with original work from the life, refines and educates both eye and hand, enforcing the utmost simplicity of handling, together with the utmost expression of form. The life model (figure) sits daily in the two life schools from ten till three o'clock—in the large life studio exclusively for the male students, and in the life room of the ladies, or the mixed class for students of either sex. The latter is pictured in our engraving. The sketch is taken during the afternoon class, when half-hour poses are arranged to assist the students in the composition subjects. In a variety of attitudes, suitable to their work, the students are grouped round the model, and in the right-hand corner a standing figure with folded arms is easily recognised as Mr. Slinger, the Professor's invaluable assistant. In this room, which is well lit and spacious, being 40 feet by 35, and 19 feet high, the Professor paints before the students; the models are grouped to assist in the composition of subjects, given out by the Professor every three or four weeks, and afterwards criticised by him. These models sit every afternoon, except Saturdays, from half-past three till five o'clock, and every half-hour a fresh position is arranged, suggested by each student in turn, to suit his or her composition. Any student may join this class on payment of model fee of 3s. 6d. per term. Very good, rapid drawings are done during these half-hour sittings. Our second, third, fourth, and sixth illustrations — by Miss Burd, the Countess Gleichen, and Miss King — sufficiently exemplify the style of drawing cultivated at them: the direct and simple method of expressing light and shade, power and action, with the least possible technical mechanism. The last illustrates the style of model which sits in the mixed class every day for five hours, so that ladies have ample opportunity for making large and carefully finished studies from the living figure, an advantage which already is — and in the course of a year or two will be still more — perceptible in the increased power and correctness of the figure paintings by our lady artists.

IV. Study in red chalk (by Miss E. S. King).

An important feature of the Slade Schools, since their enlargement during Professor Legros' tenure of [327/328] office, is the accommodation provided for the etching class. The plates are prepared, etched, and bitten in, and printed on the spot, a press having been set up for this purpose. There are about twenty students in this class, and a prize is offered each ses¬ sion for the best original etching. A list of prizes may not be uninteresting, as it will help to classify the different branches of instruction. Painting from Life, £10; Drawing from Life, £5; Landscape, painted during the vacation, £5; Painting from the Antique, £3; Drawing from the Antique, £2; Composition, £10; Anatomical Drawing, £2; Etching, £5; Anatomy, £3. Only those students compete who have attended the schools during the whole session; they must also previously have made preliminary drawings consisting of a head, hand, foot, and figures from the antique, and, unless specially exempted by the Professor, a couple of osteological and anatomical studies. The male and female students compete under precisely the same conditions, and work from the same casts and models for the competition subjects. Two prizes cannot be taken in the same class by the one student — i.e., a student in the life or antique class cannot take a prize for both drawing and painting; nor, having taken a prize in the highest class (painting from life), may he afterwards compete in a lower class.

V. The Life Class.

The competition for the Slade scholarships (six in number, value £50 a year, tenable for three years, two of which are awarded each year) is conducted on similar principles. The competitors cannot be over nineteen at the time of the award; they are required to have passed a preliminary examination in ancient and modern history, geography, and mathematics, or one modern foreign language and English. Mr. Slade's object in fixing the age at nineteen was to encourage students to commence their art studies earlier than usual, the preliminary examination being considered a necessary safeguard against the neglect of the general education. It is Professor Legros' practice to judge and decide from the work of the student during the session, as well as from that done in the more formal competition; this latter con¬ sists of a drawing of a head and figure from life, a painting from the antique, and a composition from a given subject. The Slade scholars are required to work in the classes of the schools during the tenure of their scholarships, to render any assistance in teaching, and to attend any course of lectures which the Professor shall direct; and he makes a half-yearly [328/329] report of their progress and conduct to the Council of the College.

VI. Study in red chalk by Miss E. S. King.

Within the last year Professor Legros — facile princeps among modern medallists as among modern etchers — has founded a class for the production of medals. Many of the Slade girls evince considerable taste for the work, and a recent competition resulted in the prize being awarded to Miss Elinor Hallé, daughter of the distinguished musician. In her obverse she has, as our illustration will show, produced a good likeness of her father which is also a finely-drawn, vigorously-modelled head the reverse presents a charming allegory of the Genius of Music.

At the beginning of this paper the exceptional advantages offered to lady students in the Slade Schools were pointed out. During the first years of its existence there were more women than men. Now the numbers are pretty equally divided, owing, probably, to the fact that ladies can now enjoy elsewhere, though in a lesser degree, advantages which at one time were only obtainable at the Slade Schools. An analysis of the competition lists since the foundation shows that five Slade scholarships and twenty-two prizes have been carried off by female students. Bearing in mind that the schools are but now in their eleventh session, and that many of the prizes, such as those for landscape, etching, anatomy, and anatomical drawing, are of more recent institution, the proportion of prizes gained by ladies is not insignificant j and from the ranks of former Slade students many have obtained a position of standing among the artists of the present day: Miss E. Pickering, Miss Kate Greenaway, Miss Hilda Montalba, Mrs. John Collier (née Huxley), Miss Jessie Macgregor, Miss Edith Martineau, and Miss Stuart-Wortley having all, for a longer or shorter period, sought within the walls of University College the aids to study denied to us elsewhere.

Created 21 December 2018