"Upon my word, friend," said I, "you have almost made me long to try what a robber I should make." "There is a great art in it, if you did," quoth he. "Ah! but," said I, "there's a great deal in being hanged." — Life and Actions of Guzman d'Alfarache. — Title-page.

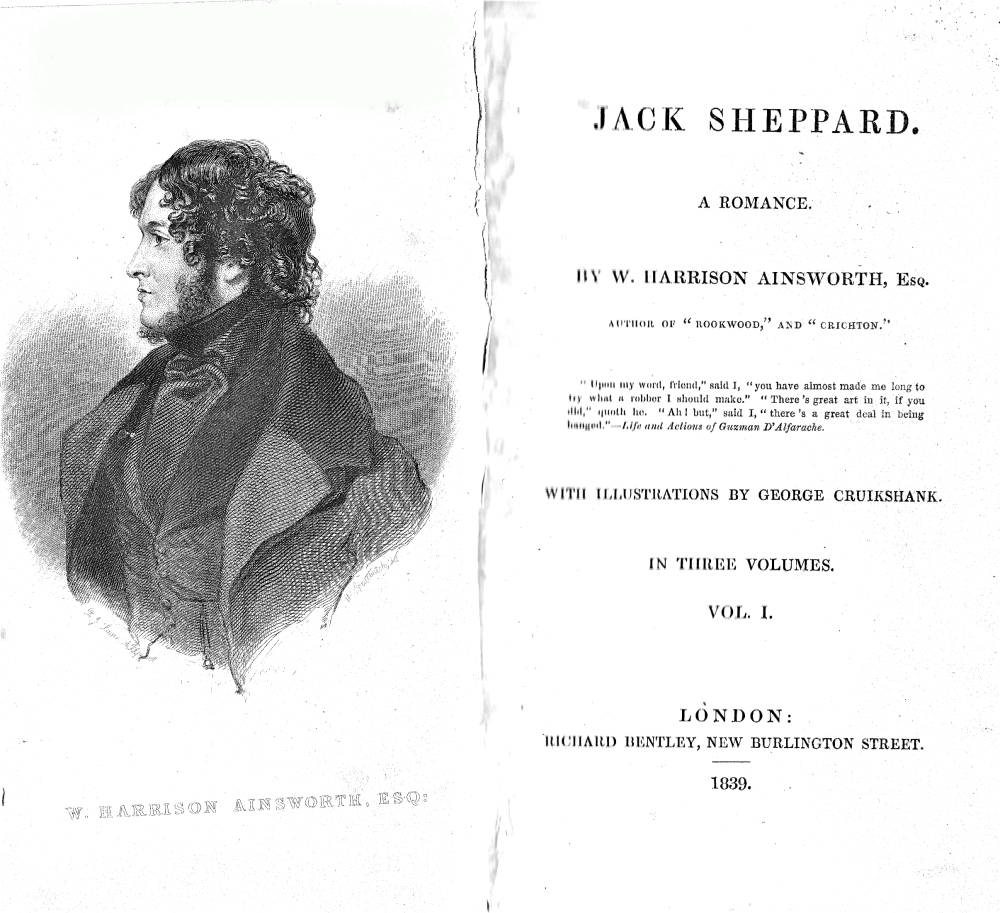

Above: George Cruikshank's Frontispiece for Jack Sheppard. A Romance by W. Harrison Ainsworth, Esqu., author of Rookwood, and Crichton. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

The second major novel in Bentley's Miscellany, Jack Sheppard. A Romance (1839), which he wrote as his monthly contribution from January 1839 though February 1840 as he took over the editorship of the monthly mixed-genre, illustrated journal from Charles Dickens, reveals William Harrison Ainsworth at his best in terms of characterisation and plot construction. Wishing to avoid a loose succession of incidents in the picaresque style, the thirty-four-year-old Ainsworth (a handsome figure indeed in George Cruikshank's flattering frontispiece to volume one) introduces two characters — the quasi-historical anti-hero Jonathan Wild and the entirely fictional hero Thames Darrell — unify this tale set in early eighteenth-century England, a setting reinforced by the period costumes in the monthly illustrations by George Cruikshank, then a well-established, forty-seven-year-old visual satirist. In a manner reminiscent of various television and film versions of The Fugitive, the thief-taker and evil genius Jonathan Wild relentlessly pursues the guiltless, noble-hearted Thames Darrell and the subtle and cunning Jack Sheppard, thief and house-breaker. Because Jack's mother has rebuffed Wild's sexual advances, Wild entices Jack's father and then Jack himself into committing crimes that will inevitably lead them to the gallows at Tyburn. Whereas Jack chooses the path of vice, his foil, Thames Darrell (like Jack in youth apprenticed to the kindly Mr. Wood, a London carpenter, and like Jack, the son of a father who has died violently after abusing his wife) chooses the path of virtue. Thames ultimately prospers with the aid of Jack's second-in-command, Blueskin, and wins the hand of the lovely Winifred, his master's daughter. Although the protagonist, Jack, is reconciled with his mother and saves both Thames and Winifred from Wild, he is ultimately hanged for his crimes. Poetic justice, however, is served when the narrator reveals that within seven months Wild himself is hanged. Cruikshank seems to have composed his illustrations with the staging of the story in mind because they leant themselves to tableaux on stage.

Because the forerunner of the public library, the private lending library, such as Mudie’s, was the principal buyer of novels in the early nineteenth century, Richard Bentley published the latest Dickens fiction Oliver Twist (still months away from the conclusion of its serial run in Bentley's Miscellany) in the so-called “triple-decker” (three-volume) format to make the new publication attractive to lending libraries. Whereas a single volume novel had limited circulation potential before it fell apart, the triple-decker set offered the possibility of three times the circulation, as each volume could be signed out by a different customer: one just starting to read the story of Oliver in the workhouse; one in the middle section, when Oliver meets Fagin and Bill Sikes; and a third customer, eagerly trying to find out eye to the main chance and to the pre-Christmas book-trade, published another "Rogue Novel" (Jack Sheppard. A Romance) in precisely the same format exactly one year after the triple-decker Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress, when it was still under serialisation in Bentley's Miscellany. Needless to say, Ainsworth provides an admirable rogue as his protagonist, in contrast to the villainous Fagin and the loutish Bill Sikes in the Dickens novel of the previous year in Bentley's Miscellany.

The eighteenth-century novelist Daniel Defoe, fascinated by the historical Jack Sheppard's daring prison escapes, wrote a pseudo-autobiography, A Narrative of all the Robberies, Escapes, etc., of John Sheppard in 1724, the same year as Sheppard's death at the age of twenty-two. The real Jack Sheppard was sentenced to be hanged at Tyburn, bringing to an end his daring career as a criminal and escape-artist. However, so popular hero was Jack that weeping women lined the route from Newgate Prison to his execution at Tyburn, dressed in white and throwing flowers in his path. Nevertheless, Sheppard had planned one last great escape. Daniel Defoe and Appleby, the publisher, planned to retrieve the body after the requisite 15 minutes on the gallows and to revive the heroic escape-artist. However, the numerous onlookers, unaware of this plan, surged toward the scaffold as its trap door opened to ensure the condemned youth a speedy death by pulling his legs. That very night he was buried in the cemetery of the church of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, London, now opposite the monument to another national hero, Horatio Lord Nelson, in Trafalgar Square.

Even after his execution on the gallows in 1724, Jack Sheppard remained famous for his daring prison escapes rather than for his crimes. So much so, popular plays about him were written and performed after his death. John Gay based the character of his romantic protagonist, Captain Macheath, in The Beggar's Opera (1728) on the public persona of the dashing Sheppard, whose exploits had made him a legend in his own time. When Ainsworth made the historical Sheppard into a handsome adventurer in a "rogue novel," the book proved so popular that the authorities regulating the British stage, the Lord Chamberlain and the Examiner of Plays, refused to license any "Jack Sheppard" plays lest young men be incited to commit such crimes as house-breaking — the ban was to last for forty years, and extended even to Oliver Twist, whose rogues all come to as bad an end as Jack Sheppard himself.

The novel appears in three forms — first in monthly instalments in Bentley's Miscellany (January 1839-February 1840), then as as a Bentley triple-decker in October 1839, and finally in fifteen weekly numbers in 1840. Ainsworth's Jack Sheppard is loosely based on the William Hogarth's famous twelve-part series of engravings entitled Industry and Idleness (1747), and the novelist also incorporates some aspects of Gay's The Beggar's Opera (1728), both inspired by the brief but sensational criminal career of the historical Sheppard. Utilising the old motif of the lazy and industrious apprentices, Ainsworth balances the anti-hero Sheppard with his fellow carpenter's apprentice, the virtuous Darrell.

The novelist has divided the story into three acts, as is appropriate to the novel's theatrical style. "Epoch the First, 1703," which takes place in one night when the main protagonists are new-born babies, acts as a prologue, introducing the reader to the setting, eighteenth-century London, and to the boys' master and adoptive father, the carpenter Owen Wood. Although Darrell's father disappears from the plot after his murder on the Thames, the villainous Jonathan Wild and his confederate, the malevolent aristocrat Sir Rowland Trenchard. "Epoch the Second, 1715," which takes place over just a few days in June of that year, tells the story of the adolescent Jack's fall from grace and into the clutches of the evil thief-taker and criminal mastermind, Jonathan Wild (to say nothing of the beds of Edgeworth Bess and Poll Maggot). The virtuous apprentice, Thames, meanwhile, falls under the malignant influence of his uncle, Sir Rowland Trenchard, Wild's silent partner. "Epoch the Third, set in 1724," covering the six months leading up to Jack's capture, incarceration, and execution, opens with Jack at the height of his success as a depraved criminal. Disgusted at a murder which transpires during a robbery arranged by Wild, Jack turns against him and spends much of the remainder of the narrative assisting Thames in restoring his family's fortunes, except when incarcerated. Jack's being jailed in some of eighteenth-century England's strongest prisons permits the novelist to recreate the daring escapes which had guaranteed the historical Sheppard his place in the Newgate Calendars. Eventually, Wild turns against and murders Sir Rowland Trenchard, and then traps Jack at his mother's grave. Despite the efforts of his companion in crime, Blueskin, and a mob of admirers to save him, Jack dies bravely on the gallows. However, Thames's birthright as a marquis has been established, and he marries his childhood sweetheart, Winifred, his old master's daughter. Finally, Ainsworth provides a poetically just closure when he announces that Wild was convicted and hanged, "seven months afterwards, with every ignominy, at the very gibbet to which he had brought his victim" (volume 3, p. 311).

Above: George Cruikshank's Frontispiece and the 1839 triple-decker title-page for volume one. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Related Materials

- The illustrations of George Cruikshank for Jack Sheppard: A Romance (1839)

- William Harrison Ainsworth (1805-1882) — King of the Historical Potboiler: A Brief Biography

- A Chronology of William Harrison Ainsworth (1805-1882)

Bibliography

Ainsworth, William Harrison. Jack Sheppard. A Romance. With 28 illustrations by George Cruikshank. In three volumes. London: Richard Bentley, 1839.

Ainsworth, William Harrison. Jack Sheppard. Edited by Edward Jacobs and Manuela Mourao. With 31 illustrations. Peterborough, ON: Broadview, 2007.

Carver, Stephen. Ainsworth and Friends: Essays on 19th Century Literature & The Gothic. Accessed 1 November 2016. https://ainsworthandfriends.wordpress.com/2013/01/16/william-harrison-ainsworth-the-life-and-adventures-of-the-lancashire-novelist/

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1846.

Meisel, Martin. Chapter 13, "Novels in Epitome." Realizations: Narrative, Pictorial, and Theatrical Arts in Nineteenth-Century England. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989. Pp. 247-282.

Sutherland, John. "Jack Sheppard" in The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 19893. Pp. 323-324.

Vann, J. Don. "Jack Sheppard in Bentley's Miscellany, January 1839 — February 1840." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985. Page 19.

Last updated 21 November 2016